3 Trade: Preferences and Interests Groups

Learning Objectives

- Define interest groups in the context of international political economy and explain their role in shaping policy outcomes.

- Define the concept of trade preferences, and understand how they impacts the international political economy.

- Analyze the different types of interest groups, including business groups, labor unions, and environmental organizations, and understand how they represent and advocate for their members’ preferences.

- Understand the concept of preference formation and how it relates to interest group influence in the policymaking process.

Introduction

Preferences and interest groups in trade are central topics in international political economy (IPE) and have gained increasing attention in recent years. This surge in interest can be attributed to the fact that trade has become a key driver of economic growth, prosperity, and development in the global economy. Free trade has in the past been seen as the optimal solution, but preferences and interest groups complicate the picture. Preferences and interest groups make it difficult to achieve a level playing field. Specifically, preferences and interest groups can create inefficiencies that can undermine the benefits of trade liberalization.

The potential for some industries or groups to gain an advantage over others is a fundamental issue in IPE. Such distributional conflicts can happen in a variety of ways, including through protectionism by the government, subsidies, or tariffs. These policies may occasionally be influenced by influential interest groups with the power to influence lawmakers and decision-makers. For instance, manufacturers may advocate for tariffs on imported goods while farmers may advocate for agricultural subsidies. These regulations may result in increased consumer costs, lower quality goods, and decreased domestic industry competition. The possibility for trade disputes between nations is another problem connected to trade preferences and interest groups. Trading partners may become tense and at odds when one nation’s interest group is given preference over another. This may result in punitive actions like tariffs, which may then intensify into trade wars. The global economy, as well as businesses and communities that depend on international commerce, can be significantly harmed by such disputes. Today, these issues are being studied and addressed by researchers. It has been argued by many economists that free trade is the best way to promote economic growth and development. At the same time, they also acknowledge that there are situations where trade preferences and interest groups need to be considered. Many have begun to argue and support for temporary protections to help developing countries. These protections are seen as a guideline for these developing nations as they attempt to build their own industries. Others argue that certain industries may require subsidies to maintain competitiveness. Governments around the world have taken a variety of approaches to dealing with trade preferences and interest groups. Some have begun implementing protectionist policies to support domestic industries. Others have sought to reduce barriers to trade and increase market access. Over the years the support for the trend towards bilateral and regional trade agreements that attempts to balance interests has increased.

Interest groups play an incredibly important role in free markets; they are defined as a collective that either loses or gains from the distributional changes of trade policy and therefore have a strong interest in how legislation concludes both domestically and internationally. They use their preferences to help order outcomes within an interaction and analyze those in order to achieve best-case scenarios. Because there are both winners and losers, we’ll examine how outcomes are tiered and why interest groups and their preferences are central to international relations and global trade.

The importance of these groups is evident in almost every piece of legislation passed domestically, and internationally. Tariffs, foreign policy, elections, and many more aspects of a governmental organization are defined by Interest groups and their preferences. Interest groups are a great way for citizens to organize and attempt to make their needs, views, and ideas known as a collective. In global trade, Interest groups and their preferences play a central role in deciding how tariffs and regulations are decided by governments. Often, the argument between liberalization and protection becomes a priority and leads to both winners and losers with policy changes. For example, a nation and relevant interest groups may prefer democratic partners instead of authoritarian regimes and state-owned entities, which may lead to tariffs on non-democratic nations and trade agreements between more politically aligned countries. For certain sectors, this is considered a loss as that trade partner could have been integral to their production needs. For some groups, this helps strengthen their position in a once tighter market or helps them push their political agenda further. This can also lead to large scale issues as trade preferences pushed by interest groups may isolate or anger another nation, leading to retaliatory tariffs and further polarization. Smaller nations with less negotiating capital to offer may find it hard to compete globally as interest groups will have their preferences focused on more robust economies that offer higher volume and more potential as a preference-receiving nation. It’s important to note that there are also issues related to the domestic production of items when preferences are given to foreign countries. If, for example, preferences are given to Haitian manufactured apparel, it results in a production adjustment domestically. In the long term, the sector may become vulnerable to supply disruptions, natural disasters, and geopolitical turmoil involving Haiti. Interest groups vary from corporations to loosely organized community groups, and have long been involved in international affairs, however as free markets have progressed, they have less room for leverage as regulations and tariffs have lessened overall.

It should now be apparent to the reader that trade preferences and special interest groups are enormously important when understanding both the way in which states engage in trade globally as well as internally, not to mention the longstanding effect both trade preferences and special interest groups have politically. These concepts will first be discussed at the macro level, before being broken down to their most fundamental theories; let us first take a look at the types of interest groups and how trade preferences appear in practice.

Later in the chapter, we’ll dive into theories that help classify interest groups, like the factor and sector theories, and how these help predict winners in trade. To go further, we’ll also touch on Adam Smith and both comparative and absolute advantages and how we use them to help define the modern economy.

Types of Interest Groups

Interest groups are organizations that represent the views and preferences of specific groups of actors, such as businesses, labor unions, and environmental organizations. These groups aim to influence government policies that affect their members’ interests by lobbying policymakers and contributing to political campaigns. Interest groups often have significant financial resources, extensive networks, and specialized knowledge, which can enhance their influence in the policymaking process. However, interest groups may also face collective action problems, where coordinating and mobilizing members may be difficult. Moreover, interest group influence may be seen as undemocratic, as some groups may have more access and influence than others. It is, therefore, essential to analyze the different types of interest groups and understand how they represent and advocate for their members’ preferences, as well as evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of their influence in the international political economy.

Trade Preference in IPE

When trade preferences and interests are manifested in the international political economy, they take on different forms. Interest groups are prevalent actors in the IPE, and when viewed in the context of international trade, such groups often possess a larger role than any one state on its own. Regional trade agreements, for example, are rather common agreements between two or more countries within a specific region that aim to liberalize trade and deepen economic integration among member countries. RTAs can take various forms, such as free trade agreements, customs unions, economic unions, and common markets. An example of a prominent RTA is the European Union, which is a regional trade agreement driven by trade preferences and interests, promoting intra-regional trade and protecting domestic markets. The implementation and enforcement of RTAs also reflect the trade preferences and interests of its member countries, as they interpret and implement these provisions based on their own domestic priorities and interests.

Moreover, the evolution of regional trade agreements over time also reflects the changing trade preferences of member countries. RTAs may undergo renegotiations or revisions to accommodate shifting priorities and dynamics while new trade rules, norms, and institutions may also emerge within regional trade agreements based on the evolving preferences and interests of member countries. For example, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) was a regional trade agreement that aimed to set high standards for trade and investment among Pacific Rim countries. However, the withdrawal of the United States from the agreement in 2017 led to its renegotiation and eventual transformation into the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which excluded some provisions that were previously favored by the United States.

Another way that one can consider trade preferences and interests is through the lens of developing nations versus developed nations. Each has distinct trade preferences in the scope of the international network, and these preferences are shaped by their unique challenges and position in the global economy. Developing countries often rely on international trade as a crucial source of jobs, economic growth, and poverty reduction; their trade preferences typically revolve around gaining access to new and profitable markets and promoting export-oriented industries so that they may take advantage of any natural resources they have access to.

At the same time, developing countries and their IGs may also have interests in protecting their domestic markets and industries from competition, safeguarding their agricultural sectors, and promoting domestic value-added activities. Developing countries may use trade policy measures, such as tariffs, quotas, and export restrictions, to protect their domestic markets or industries from import competition and promote their domestic production. This is often driven by the need to safeguard domestic employment in order to protect small and medium-sized enterprises and preserve food security. For example, many developing countries impose tariffs or non-tariff barriers on agricultural products to protect their domestic farmers from competition with heavily subsidized agricultural products from developed countries.

Developed countries have their own distinct trade policy preferences, usually looking to drive economic competitiveness and prioritize political interests. This can entail aiming to secure access to new markets, reducing trade barriers, and optimizing regulations to secure the flow of investments. These countries will seek to gain preferential treatment in their trade agreements and are often able to do so due to their prominent position in the IPE.

Strategic considerations also play a large part in shaping the trade preferences of the interest groups of developed countries. They seek to strengthen their geopolitical influence and promote their values and norms, while countering the influence of other countries. They can use regional trade agreements as a tool for diplomatic engagement and alliance building. The EU has often done just this, as a part of its broader foreign policy objectives to promote stability, security, and prosperity in its neighborhood.

Despite their far-reaching goals and interests in global affairs, developed countries must maintain a respect for domestic political considerations. Governments and interest groups face pressure from internal stakeholders such as domestic industries, labor unions, and civil rights groups, which leads them to consider these preferences and seek to include provisions in trade agreements that address these political concerns. For example, labor and environmental standards, intellectual property rights, and investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms are often contentious issues in regional trade agreements involving developed countries.

While this discussion has outlined some of the optimal decision making for interest groups and countries in specific situations, it is important to note that not all act in their own best interests when faced with the global arena of trade; whether it be through inefficiencies, a lack of expertise in political decision making, or the distorting pressures of interest groups, many actors end up losing through trade. The following section will elaborate on these concepts and provide a framework for explaining the tiered outcomes of trade. To begin with, it is imperative to discuss some key terminology and theories that help us to understand why trade preferences and special interest groups are such a large and important voice within most if not all markets globally, both large and small. With that said, we will transition into discussing Adam Smith and Ricardo Viner and the issues of Absolute Advantage and Comparative Advantage.

Background Theories on Trade Preferences and Special Interest Groups

When discussing trade on a global scale, it is almost impossible to not include Adam Smith in the discussion. In this instance, Smith highlights correctly that the division and specialization of labor is how a modern economy grows as workers become more and more specialized and proficient in ever more detailed roles. This makes sense when one considers the time that Adam Smith lived in. Living during the age of Enlightenment in the United Kingdom, Smith saw the United Kingdom and western Europe as a whole, begin to industrialize at a rapid rate during the Scientific Revolution. As factories and fabrication of goods replaced the cottage and village industry which had been a constant of human society since the advent of agriculture, the need for specialized labor as opposed to the generalist labor roles of the dark ages such as carpenters or smiths soared to an all-time high, this was the truest in the most industrialized nation at the time, the United Kingdom. Adam Smith, looking at the fast-developing economy of his nation came up with a host of theories which have rightfully earned him the title of “Father of Modern Economics”, the most prevalent of his theories in our discussion of Trade Preferences and special interest groups is found within his Magnum Opus, The Wealth of Nations. In his book, Smith touches upon the division and more specifically, the specialization of Labor. He goes on to outline two types of advantages a country can have when engaging in international trade, these advantages being Comparative and Absolute. A comparative advantage is when a country can produce a good more cheaply and efficiently than it can produce other goods. On the other hand, an absolute advantage is when a country can produce goods for less of a cost than the country it is trading with. While both these ideas have been studied at length and deserve their own detailed discussion, the importance of comparative and absolute advantages towards trade preferences and special interest groups is that they are the most fundamental method of looking at what a country should specialize in producing, this in turn is what creates both trade preferences and special interest groups which seek to gain or further protections from their countries that align with the goods that they are producing. While absolute advantage has largely fallen out of favor as a driver for international trade, comparative advantage is the framework through which we understand free trade in the modern day.

In this vein of thought, another vastly influential Enlightenment Era scholar, David Ricardo, expanded upon the discussion of comparative advantage. Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage is often lauded as the logical backbone for the free trade argument from its inception over 200 years ago to the modern day. From Ricardo, we glean some key insights into how and more importantly when,countries should trade with each other as well as to what extent. Ricardo based his theory of comparative advantage in international trade in accordance with the relative difference amongst countries’ opportunity costs, which he saw as the driving factor for efficient free trade as well as specialization within countries. Furthermore, Ricardo’s model was based upon the Labor Theory of Value, which in essence counted Labor as the first and foremost means of production. Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage would go on to influence the economists Hecksher and Ohlin, who brought the discussion of comparative advantage to the modern day and provides us with the key framework of understanding the existence of Trade Preferences and Special Interest Groups and why they play a pivotal role in the makeup and trajectory of modern economies of scale.

H-O Model, Specific Factors Model, and the Development of Trade Preferences

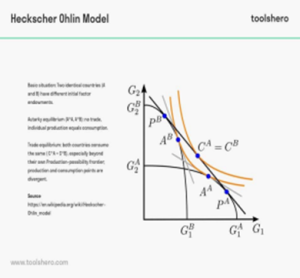

The Heckscher-Ohlin Model (referred to as the H-O model from here on out) was developed by the Swedish Economist Eli Hecksher near the turn of the century and was expanded upon by his student at the Swedish School of Economics, Bertil Ohlin. Seeing the ever-changing socio-economic landscape of Europe at the time, Hecksher sought to reevaluate the works of Smith and Ricardo towards the now heavily capital-intensive markets of Europe at the turn of the century. It is from this outlook that the predictions and general principles of the H-O Model arise. Following Ricardo’s thoughts on comparative advantage, the H-O model’s basic principle is that all countries have finite resources of land, labor, and capital amongst others. In this vein of reasoning, as opposed to Ricardo’s single, labor factor view, a country’s comparative advantage is developed from creating products based on its most prevalent factor. In this two-factor system, when nations specialize, free trade should benefit all nations which take part in efficient trade. However, some paradoxes or seemingly irrational trade takes place against the H-O model’s predictions. For example, the United States, an extremely capital-intensive market, more often exports labor- intensive products; in the same vein, only about half of capital-abundant nations export capital intensive products. While some of this can be accounted for by a lack of trade between global north and global south nations until recently, much of it can be explained by trade preferences between global north nations.

The Specific Factors model is best understood as a sort of synthesis between Ricardian Theory and the H-O model. The way the Specific Factors model works is like Ricardian Theory, this model assumes that a country that produces two or more goods can also adequately allocate labor between the production of these two different goods. However, unlike the Ricardian Theory, the Specific Factors Model incorporates other factors outside of labor, in line with the H-O model, if they are specific to one of two goods. The key assumptions or predictions drawn from the Specific Factors Model is that trade will occur when relative prices differ, countries will trade whatever goods they can produce the most cheaply, and most importantly to the discussion of trade preferences, specific factors in export sectors while those in import-competing sectors lose.

Both the H-O and the Specific factors model cannot be right. Neither model predicts trade flows very well, and the gravity model, which is a separate model that predicts how much states will trade based on their size, their proximity, and other characteristics, has shown the most success. Despite this success, it has been largely unknown why it works so well- until recently.

Michael Hiscox, a political scientist, looked at these models of trade in 2002 and found that perhaps both models are correct, asserting that the usage of the models depends on how mobile certain factors are in a given period. Therefore, if we were able to measure how mobile said factors are, we can know which trade theory to use to predict trade politics. This concept, combined with the model, could prove to be a useful tool in predicting the impact of trade on politics and vice versa. It is as if one is putting together the pieces of an equation; a formula where the missing variable can be determined if all other variables are known.

Trade Preferences and Special Interest Groups in Relation to International Trade

Understanding the H-O Model and the Specific Factors Model in the context of trade preferences and special interest groups is crucial to comprehending the complexities of international trade dynamics. These models provide and illustrate the foundation for understanding how trade preferences are formed between nations and how special interest groups influence trade policies at both national and international levels.

International trade creates trade preferences and alliances between nations for various reasons, such as maximizing profits or strengthening political ties. These preferences can often seem incongruent with the predictions of trade models, but they can be explained by the concept of trade preferences. For example, the United States may export more labor-intensive products to countries with similar preferences among global north nations, despite having abundant capital. Do note, however, that trade preferences are not static and can change over time.

Trade preferences are significant in building a useful model for understanding how countries interact economically and why there are hindrances to global free trade. Trade agreements are established based on trade preferences, and these agreements can shape the flow of goods and services between countries and impact trade patterns and economic relationships.

Special interest groups, particularly in capital-intensive markets, play a crucial role in shaping international trade policies. These groups, typically composed of powerful corporations, lobby for preferential legislation and trade policies to protect or expand the markets they are involved in. Their influence on trade policies can have far-reaching effects on a country’s economy, including subnational impacts on dietary patterns, energy consumption, and labor markets.

For example, soy and corn farmers in Iowa have significant influence over energy consumption and food availability in North America through their lobbying efforts. Dairy farmers seek protections from the federal government in the pricing of milk, which can have implications for the availability and affordability of dairy products in the market.

Understanding the role of special interest groups is essential in comprehending the complexities of international trade dynamics. As these groups often have significant power and influence over trade policies, their interests and preferences shape trade patterns and economic relationships; it is such that trade preferences and special interest groups are inherently intertwined. These groups lobby for preferential treatment or protectionist policies to benefit their industries, and in reverse, trade preferences can shape the interests and strategies of special interest groups, as they seek to take advantage of preferential trade agreements or alliances. However, it should be noted that special interest groups may not always align with the broader national or global interests, and their influence can sometimes lead to distortions in trade patterns and hinder the benefits of free trade.

Trade preferences and special interest groups play significant roles in shaping trade policies and influencing trade patterns and economic relationships between nations. By considering the interplay between these factors, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of why international trade often deviates from the predictions of trade models and how trade preferences and special interest groups impact global trade dynamics.

Conclusion

With a better understanding of the broad categories of interest groups and their preferences, we can now explore areas where changes in geopolitics might lead to new developments. The changing political landscape of the 2020s and shifts in the position of workers may lead to a new wave of unionization efforts at large companies like Amazon and Starbucks, leading to new coalitions advocating for their preferences on trade policy. It will be important to observe how the increased organization of labor impacts their preferences and ability to advocate for them, as well as how multinational corporations react to this labor movement.

Another area that requires observation is the trade policy preferences resulting from the resurgence of NATO amid Russian aggression in neighboring countries. Significant actions like war lead to political costs for businesses, and in recent years, consumers have increasingly looked towards businesses in the political sphere. As a result, these costs may change preferences regarding trade policy. For example, corporations may prefer reduced trade barriers with oil-rich countries to access resources without having to deal with Russia.

The continuing progression of globalization and the increase or decrease in connectivity will also lead to changes in preferences from every interest group. In studying trade preferences, it is important to note that outcomes are not indicative of individual actor preferences but rather the confluence of preferences from all involved actors. The factor theory and sector theory are particularly useful in classifying types of interest groups, as they predict different winners of trade, leading to different policy choices that different interest groups will advocate for.

It is certainly important to determine what interest groups are more likely to be effective in advocating for their preferred policies. Larger groups have more collective action issues, as organizing more competing interests requires overcoming more obstacles, but firms generally have fewer issues than consumers. Protectionist interests tend to be advocated for by specific domestic business interests because those businesses benefit from reduced international competition. Consumers tend to benefit from free trade, which results in lower prices from more competition. However, protectionist measures and policies tend to be advantaged or overrepresented in policy because firms are better at advocating than consumer groups.

One example of this is the Corn Laws enacted in Britain in 1815, which were protectionist tariffs on grain from outside Britain. Landowners supported the laws because they allowed them to charge higher prices for their grain, benefiting from reduced international competition. In contrast, non-landowners had to pay higher prices for grain products like bread and opposed the laws. Eventually, due to organizational efforts by opponents of the laws known as the Anti-Corn Law League, they were repealed in 1846. This example illustrates how economic situations and comparative advantages lead to preferences, which lead to policy that impacts preferences, leading to new policy.

In summary, this chapter has covered trade preferences and interest groups, reviewing Smith’s and Ricardo’s work and the models that influence trade preferences. We also explored real-world examples like the Corn Laws and modern American interest groups like dairy farmers. The discussion should provide readers with a fundamental understanding of what preferences are and why groups have them.

Works Cited

Carpenter, K. (n.d.). Petitions and the corn laws – committees – UK parliament. Retrieved from https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/326/petitions-committee/news/99040/petitions-and the-corn-laws/

“Comparative Advantage and Adam Smith.” Comparative Advantage International Political Economy, https://mediawiki.middlebury.edu/IPE/Comparative_Advantage.

Gabel, M.. (2004). Hiscox, M. J.: International Trade and Political Conflict – Commerce, Coalitions, and Mobility.. Journal of Economics. 81. 281-283. 10.1007/s00712-003-0029-7.

Lake, D. A., & Powell, R. (1999). Strategic choice and international relations. Princeton Univ. Press. Interest groups, lobbying and polarization in the United … (n.d.). Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4084&context=edissertatio ns

Newnham, Randall E. “Georgia on My Mind? Russian Sanctions and the End of the ‘Rose Revolution.’” Journal of Eurasian Studies, vol. 6, no. 2, 2015, pp. 161–170., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euras.2015.03.008.

Los Angeles Times (2015). IMF Agrees: Decline of Union Power Has Increased Income Inequality. Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 25 Mar. 2015, http://www.latimes.com/business/hiltzik/la-fi-mh-imf-agrees-loss-of-union power-20 150325-column.html.