15

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Determine the source and nature of an arguable claim. (GEO 1)

- Use reasoning, authority, and emotion to support your argument. (GEO 1; SLO 2)

- Identify and avoid logical fallacies. (GEO 1)

For some people, the word argument brings up images of finger-pointing, hostility, or polarization. Actually, when people behave like this, they really aren’t arguing at all. They are quarreling. And when people quarrel, they are no longer listening to or considering each other’s ideas.

An argument is something quite different. Arguments involve making reasonable claims and then backing up those claims with evidence and support. The objective of an argument is not necessarily to “win” or prove that you are right and others are wrong. Instead, your primary goal is to show others that you are probably right or that your beliefs are reasonable and worthy of their honest consideration. When arguing, both sides attempt to convince others that their position is stronger or more beneficial. Their goal is to reach an agreement or compromise.

In college and in the professional world, people use argument to think through ideas and debate uncertainties. Arguments are about getting things done by gaining the cooperation of others. In most situations, an argument is about agreeing as much as disagreeing, about cooperating with others as much as competing with them. Your ability to argue effectively will be an important part of your success in your college courses, your social life, and your career.

What Is Arguable?

Let’s begin by first discussing what is “arguable.” Some people will say that you can argue about anything. And in a sense, they are right. We can argue about anything, no matter how trivial or pointless.

| “I don’t like chocolate.” | “Yes, you do.” |

| “The American Civil War began in 1861.” | “No, it didn’t.” |

| “It disgusts me that our animal shelter kills unclaimed pets after just two weeks.” | “No, it doesn’t. You think it’s a good thing.” |

These kinds of arguments are rarely worth your time and effort. Of course, we can argue that our friend is lying when she says she doesn’t like chocolate, and we can challenge the historical fact that the Civil War really started in 1861. However, debates about personal judgments, such as liking or not liking something, quickly devolve into “Yes, I do.” “No, you don’t!” kinds of quarrels. Meanwhile, debates about proven facts, like the year the American Civil War started, can be resolved by consulting a trusted source. To be truly arguable, a claim should exist somewhere between personal judgments and proven facts (Figure 8.1).

Arguable Claims

When laying the groundwork for an argument, you need to first define an arguable claim that you want to persuade your readers to accept as probably true. For example, here are arguable claims on two sides of the same topic:

Examples of Arguable Claims

Marijuana should be made a legal medical option in our state because there is overwhelming evidence that marijuana is one of the most effective treatments for pain, nausea, and other symptoms of widespread debilitating diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, cancer, and some kinds of epilepsy.

Although marijuana can relieve symptoms associated with certain diseases, it should not become a legal medical option because its medical effectiveness has not been clinically proven and because legalization would send a message that recreational drugs are safe and even beneficial to health.

Both claims are “arguable” because neither side can prove that it is factually right or that the other side is factually wrong. Meanwhile, neither side is based exclusively on personal judgments. Instead, both sides want to persuade you, the reader, that they are probably right.

When you invent and draft an argument, your goal is to support your position to the best of your ability, but you should also imagine views and viewpoints that disagree with yours. Keeping opposing views in mind will help you clarify your ideas, anticipate counterarguments, and identify the weaknesses of your position. Then, when you draft your argument, you will be able to show readers that you have considered all sides fairly.

On the other hand, if you realize that an opposing position does not really exist or that it’s very weak, then you may not have an arguable claim in the first place.

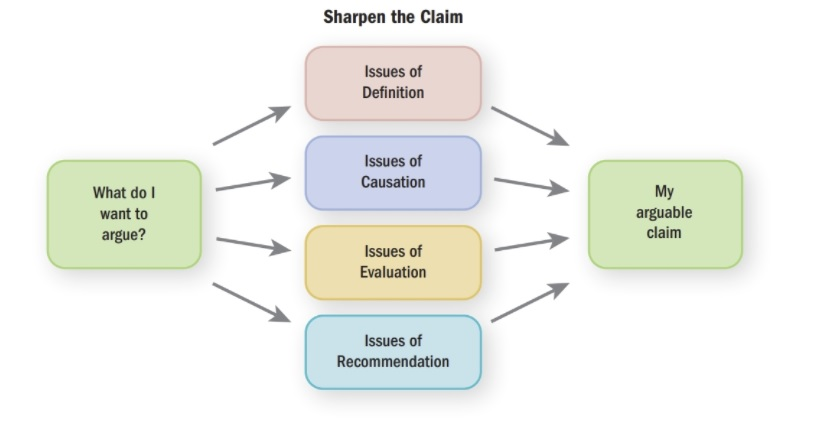

Four Sources of Arguable Claims

Once you have a rough idea of your arguable claim, you should refine and clarify it. First, figure out what you want to argue. Then sharpen your claim by figuring out which type of argument you are making, as shown in the chart below. The result will be a much clearer arguable claim.

Arguable claims generally arise from four sources:

1. Issues of definition. Some arguments hinge on how to define an object, event, or person. For example, here are a few arguable claims that debate how to define something:

Examples

When our campus newspaper published its interview with that Holocaust denier, it was an act of journalistic malpractice.

What that fraternity did was not just a “prank that got out of hand.” At the very least, it was an act of bullying. More accurately, it was assault and battery.

A pregnant woman who smokes is a child abuser who needs to be stopped before she further harms her unborn child.

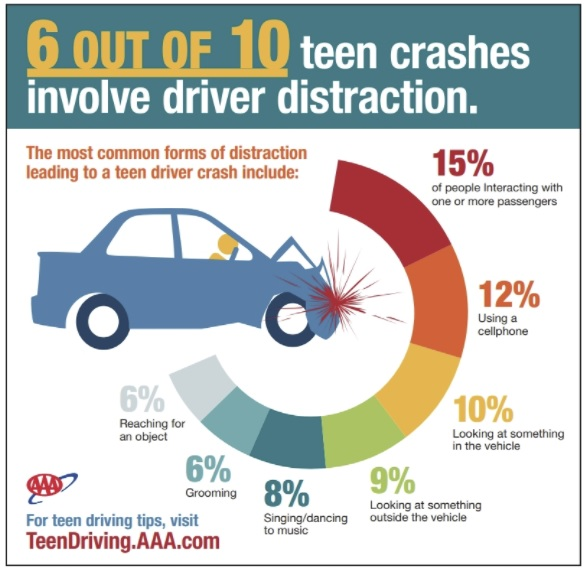

2. Issues of causation. Humans tend to see events in terms of cause and effect. Consequently, people often argue about whether one thing caused another.

Examples

Each year, texting while driving causes far more deaths than the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center.

Violent video games do not cause the people who play to become violent in their actual, lived, real-world lives.

Pregnant mothers who choose to smoke are responsible for an unacceptable number of birth defects in children.

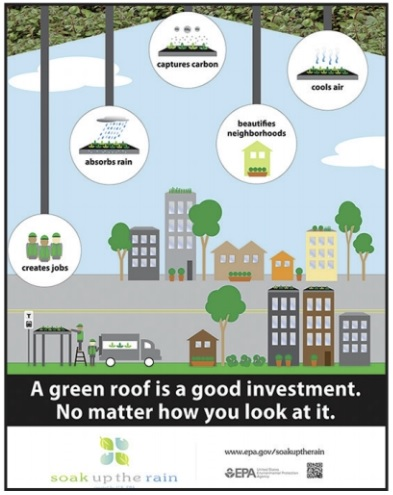

3. Issues of evaluation. We also argue about whether something is good or bad, right or wrong, or better or worse.

Examples

It’s true that the movies inspired by Marvel Comics are funny and action-packed, but for great storytelling and drama, the movies inspired by DC Comics—such as Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman—are unmatched.

The current U.S. taxation system is unfair, because the majority of taxes fall most heavily on people who work hard and corporations who are bringing innovative products to the marketplace.

Although both are dangerous, drinking alcohol in moderation while pregnant is less damaging to an unborn child than smoking in moderation.

4. Issues of recommendation. We also use arguments to make recommendations about the best course of action to follow. These kinds of claims are signaled by words like “should,” “must,” “ought to,” and so forth.

Examples

Tompson Industries should convert its Nebraska factory to renewable energy sources, like wind, solar, and geothermal, using the standard electric grid only as a backup supply for electricity.

People will keep texting while driving because the urge to stay in touch is so irresistible. Therefore, we need to make the penalties for breaking this law much harsher.

We must help pregnant women to stop smoking by developing smoking-cessation programs that are specifically targeted toward this population.

Using Logos, Ethos, and Pathos

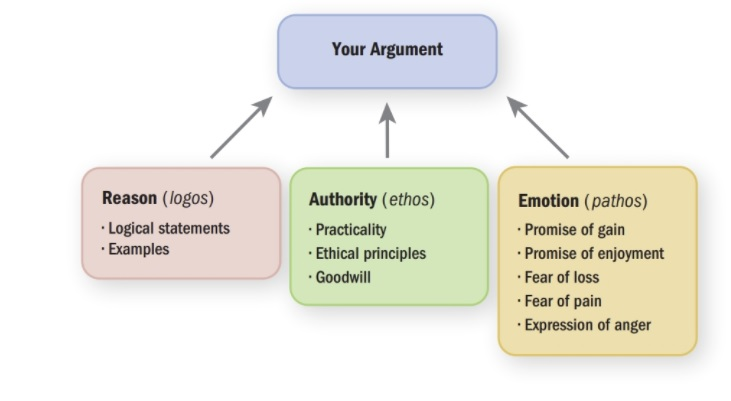

Once you have developed an arguable claim, you can start figuring out how you are going to support it. A solid argument will usually employ three types of “proofs”: reason, authority, and emotion, as seen in the chart below. Greek rhetoricians like Aristotle originally used the words logos (reason), ethos (authority), and pathos (emotion) (Fig 8.1) to discuss these three proofs.

Logos (Logos)

Logos involves appealing to your readers’ sense of logic and reason.

Logical Statements

Logical statements allow you to use your readers’ existing beliefs to prove they should agree with a further claim. Here are some common patterns for logical statements:

- If . . . then: “If you believe X, then you should believe Y also.”

- Either . . . or: “Either you believe X, or you believe Y.”

- Cause and effect: “X is the reason Y happens.” (Figure 8.1)

- Costs and benefits: “The benefits of doing X are worth/not worth the cost of Y.”

- Better and worse: “X is better/worse than Y because . . . “

Examples

The second type of reasoning, examples, allows you to illustrate your points or demonstrate that a pattern exists.

- Examples: “For example, in 1994. . . .” “For instance, last week. . . .” “To illustrate, there was the interesting case of. . . .” “Specifically, I can name two situations when. . . .”

- Personal experiences: “Last summer, I saw. . . .” “Where I work, X happens regularly.”

- Facts and data: “According to our survey results, . . . .” “Recently published data show that. . . .”

- Patterns of experiences: “X happened in 2004, 2008, and 2012. Therefore, we expect it to happen again in 2016.” “In the past, each time X happened, Y has happened also.”

- Quotes from experts: “Dr. Jennifer Xu, a scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory, recently stated. . . .” “In his 2013 article, historian George Brenden claimed. . . .”

Ethos (Ethos)

Ethos involves using your own experience or the reputations of others to support your arguments (Figure 8.2). Another way to strengthen your authority is to demonstrate your practicality, ethical principles, and goodwill. These three types of authority were first mentioned by Aristotle as a way to show that a speaker or writer is being fair and therefore credible. These strategies still work well today.

Practicality

Show your readers that you are primarily concerned about solving problems and getting things done, not lecturing, theorizing, or simply winning. Where appropriate, admit that the issue is complicated and cannot be fixed easily. You can also point out that reasonable people can disagree about the issue. Being “practical” involves being realistic about what is possible, not idealistically pure about what would happen in a perfect world.

- Personal experience: “I have experienced X, so I know it’s true and Y is not.”

- Personal credentials: “I have a degree in Z” or “I am the director of Y, so I know about the subject of X.”

- Appeal to experts: “According to Z, who is an expert on this topic, X is true and Y is not true.”

- Admission of limitations: “I may not know much about Z, but I do know that X is true and Y is not.”

Ethical Principles

Demonstrate that you are arguing for an outcome that meets a specific set of ethical principles. An ethical argument can be based on any of three types of ethics:

- Rights: Using human rights or constitutional rights to back up your claims.

- Laws: Showing that your argument is in line with civic laws.

- Utilitarianism: Arguing that your position is more beneficial for the majority of people.

In some situations, you can demonstrate that your position is in line with your own and your readers’ religious beliefs or other deeply held values.

- Good moral character: “I have always done the right thing for the right reasons, so you should believe me when I say that X is the best path to follow.”

Goodwill

Demonstrate that you have your readers’ interests in mind, not just your own. Of course, you may be arguing for something that affects you personally or something you care about. So show your readers that you care about their needs and interests, too. Let them know that you understand their concerns and that your position is fair or a “win-win” for both you and them.

- Identification with the readers: “You and I come from similar backgrounds and we have similar values; therefore, you would likely agree with me that X is true and Y is not.”

- Expression of goodwill: “I want what is best for you, so I am recommending X as the best path to follow.”

- Use of “insider” language: Using special terminology or referring to information that only insiders would understand.

Pathos (Pathos)

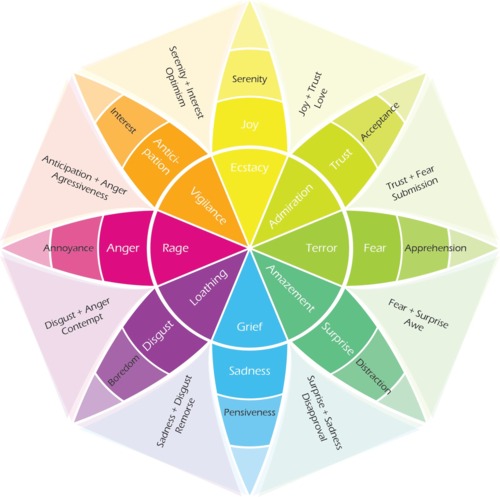

Using emotional appeals to persuade your readers is appropriate if the feelings you draw on are suitable for your topic and readers (Figure 8.4). As you develop your argument, think about how your emotions and those of your readers might influence how their decisions will be made.

- Promise of gain. Demonstrate to your readers that agreeing with your position will help them gain things they need or want, like trust, time, money, love, loyalty, advancement, reputation, comfort, popularity, health, beauty, or convenience (Figure 8.5). “By agreeing with us, you will gain trust, time, money, love, advancement, reputation, comfort, popularity, health, beauty, or convenience.”

- Promise of enjoyment. Show that accepting your position will lead to more satisfaction, including joy, anticipation, surprise, pleasure, leisure, or freedom. “If you do things our way, you will experience joy, anticipation, fun, surprises, enjoyment, pleasure, leisure, or freedom.”

- Fear of loss. Suggest that not agreeing with your opinion might cause the loss of things readers value, like time, money, love, security, freedom, reputation, popularity, health, or beauty. “If you don’t do things this way, you risk losing time, money, love, security, freedom, reputation, popularity, health, or beauty.”

- Fear of pain. Imply that not agreeing with your position will cause feelings of pain, sadness, frustration, humiliation, embarrassment, loneliness, regret, shame, vulnerability, or worry. “If you don’t do things this way, you may feel pain, sadness, grief, frustration, humiliation, embarrassment, loneliness, regret, shame, vulnerability, or worry.”

- Expressions of anger or disgust. Show that you share feelings of anger or disgust with your readers about a particular event or situation. “You should be angry or disgusted because X is unfair to you, me, or someone else.”

The psychologist Robert Plutchik suggests there are eight basic emotions: joy, acceptance, fear, surprise, sadness, disgust, anger, and anticipation (Fig. 8.5). Some other common emotions that you might find are annoyance, awe, calmness, confidence, courage, delight, disappointment, embarrassment, envy, frustration, gladness, grief, happiness, hate, hope, horror, humility, impatience, inspiration, jealousy, joy, loneliness, love, lust, nervousness, nostalgia, paranoia, peace, pity, pride, rage, regret, resentment, shame, shock, sorrow, suffering, thrill, vulnerability, worry, and yearning.

Begin by listing the positive and negative emotions that are associated with your topic or with your side of the argument. Use positive emotions as much as you can, because they will build a sense of goodwill, loyalty, or happiness in your readers. Show readers that your position will bring them respect, gain, enjoyment, or pleasure. Negative emotions should be used sparingly. Negative emotions can energize your readers or spur them to action. However, be careful not to threaten or frighten your readers, because people tend to reject bullying or scare tactics. These moves will undermine your attempts to build goodwill. Make sure that any feelings of anger or disgust you express in your argument would be shared by your readers, or they will reject your argument as unfair, harsh, or reactionary.

Avoid Fallacies

Avoid Fallacies

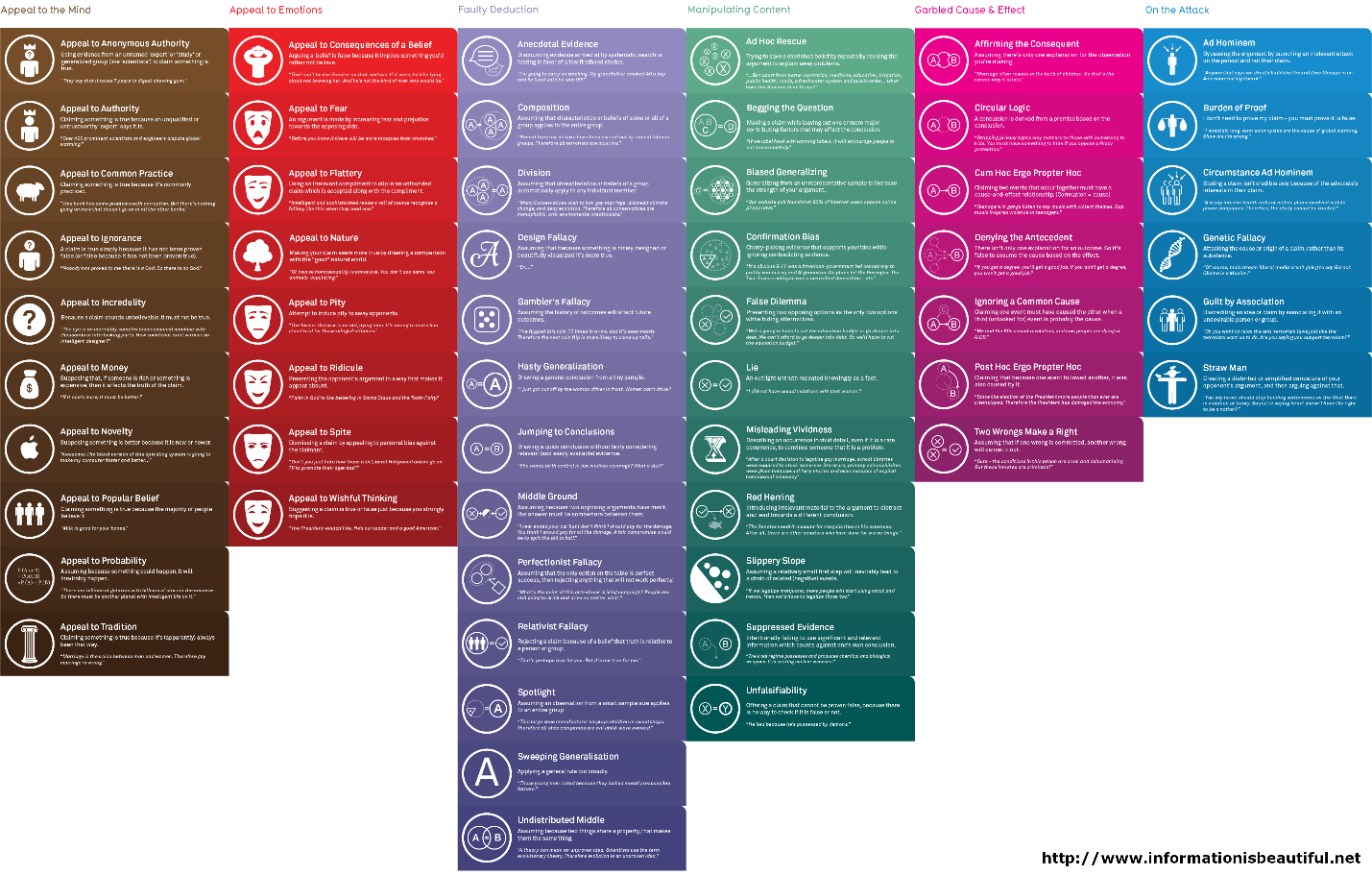

A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning. You should avoid logical fallacies in your own writing because they can undermine your argument. Plus, they can keep you from gaining a full understanding of the issue because fallacies usually lead to inaccurate or ambiguous conclusions. Figure 8.6 defines and gives examples of common logical fallacies. Watch out for them in your own arguments. When an opposing viewpoint depends on a logical fallacy, you can point to it as a weakness.

Fallacies tend to occur for three primary reasons:

- False or weak premises. In these situations, the author is overreaching to make a point. The argument uses false or weak premises (bandwagon, post hoc reasoning, slippery slope, or hasty generalization), or it relies on comparisons or authorities that are inappropriate (weak analogy, false authority).

- Irrelevance. The author is trying to distract readers by using name-calling (ad hominem) or bringing up issues that are beside the point (red herring, tu quoque, non sequitur).

- Ambiguity. The author is clouding the issue by using circular reasoning (begging the question), arguing against a position that no one is defending (straw man), or presenting the reader with an unreasonable choice of options (either/or). Logical fallacies do not prove that someone is wrong about a topic. They simply mean that the person may be using weak or improper reasoning to reach his or her conclusions. In some cases, logical fallacies are used deliberately. For instance, some advertisers want to slip a sales pitch past the audience. Savvy arguers can also use logical fallacies to trip up their opponents. When you learn to recognize these fallacies, you can counter them as necessary.

In addition to fallacies of logic, it’s important to be aware of fallacies of ethos and pathos. Check out more examples of rhetological fallacies at https://informationisbeautiful.net/visualizations/rhetological-fallacies/.

A series of statements, called the premises, intended to determine the degree of truth of another statement, the conclusion

A statement of the exact meaning of a word or idea.

Influence by which one event, process or state contributes to the production of another event, process or state where the cause is partly responsible for the effect, and the effect is partly dependent on the cause.

The making of a judgment about the amount, number, or value of something; assessment.

The making of a judgment about the amount, number, or value of something; assessment.

A rhetorical appeal to logic, reason, and common sense.

A rhetorical appeal to authority, credibility, and character.

A rhetorical appeal to emotion.

(385-323 BCE) a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato and mentor to Alexander the Great, he was the founder of the Lyceum, the Peripatetic school of philosophy, and the Aristotelian tradition.

Moral principles that govern a person's behavior or the conducting of an activity.

The doctrine that actions are right if they are useful or for the benefit of a majority.

Friendly, helpful, or cooperative feelings or attitude.

(1927-2006) An American psychologist well-known for proposing a psychoevolutionary classification approach for general emotional responses.

A mistaken belief, especially one based on unsound argument.