10

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand the role, science, and history of storytelling. (GEO 1, 2; SLO 1)

- Define folklore and its place in the study of writing. (GEO 1, 2; SLO 4)

Writing gives you the power to get things done with words and images. It allows you to respond successfully to the people and events around you, whether you are trying to strengthen your community, pitch a new idea at work, or just text with your friends. The emergence of new writing situations—new places for writing, new readers, and new media—means writing today involves more than just getting words and images onto a page or screen. Writers need to handle a wide variety of situations with diverse groups of people and rapidly changing technologies. Learning to navigate among these complex situations is the real challenge of writing in today’s world. Writing gives you the power to think critically, express your ideas clearly, and persuade others. Today, being able to communicate effectively is vital to your success in college and in your career. In this book, you will learn to use powerful communication tools that will be key to your success.

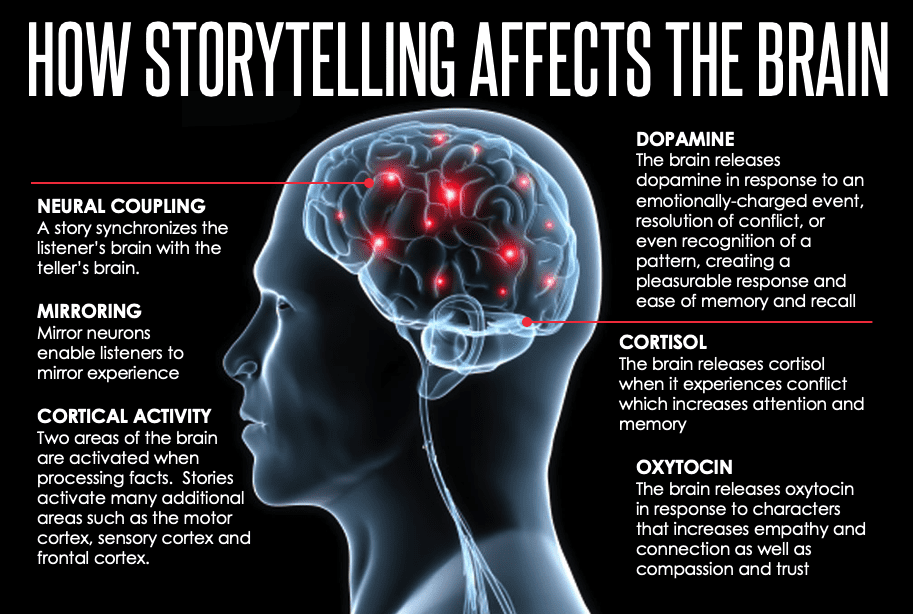

Storytelling exists throughout every time and every place, it is a part of every culture and society. The ability to tell stories is unique to humans. According to the authors of Cognitive Neuroscience: The Biology of the Mind, humans are “hardwired” to tell stories. Humans communicated stories before we developed language. In fact, storytelling is essential to our survival and growth as a species.

From “The Science of Storytelling” by Leo Wildrich:

The History of Storytelling

The Oldest (Recorded) Stories

Because humans began telling stories before we had developed a written (or even verbal) language, to study the first stories ever recorded, we need to look at a different medium: art. While many stories have been lost to time, the cave paintings left by our ancestors provide us with valuable information about their lives and beliefs. Historical records show that Homo sapiens (meaning “the one who knows”) came into being at least 315,000 years ago in Africa. During the Paleolithic (a.k.a. Stone Age) period (~40,000-10,000 BCE), Homo sapiens began migrating to the Eurasian continent, supplanting Homo erectus (Neanderthals) in Europe. The first Homo sapiens in Europe are called Cro Magnons.

What is known of Paleolithic life derives largely from cave paintings. There is no indication that the tribes actually lived in caves. People at this time were hunter-gatherers. They were nomadic and followed herds. Prehistoric art is thought to be related closely to a tribe’s rituals and religion. One theory posits that painting animals had the power to bring more animals to the tribe. Another holds that painting animals over other animals was representative of mating. It’s possible the tribes believed in sympathetic magic, that painting something held the power to make it come true. Since these sites held such power for tribes, only key individuals were allowed inside to perform the rituals and only religious leaders could paint on the walls.

Some of the oldest and most famous cave art is shown below. The older examples are more rudimentary. The art became larger, more vivid, and more detailed as time progressed. Eventually, people drew and painted on cave walls as though they were telling stories with their art. For this reason, the Cave of Lascaux is considered the oldest recorded story. You can take a virtual tour of the Lascaux Cave here.

The Paleolithic (Stone Age) period evolved into the Neolithic (New Stone Age) period around 10,000-3,000 BCE. Around the world, tribes began giving up their nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles and instead began domesticating animals and planting crops. Thus, the agricultural revolution was born, and with it, many other groundbreaking inventions such as the wheel. Now that people were living in permanent settlements, we see civilizations form.

The Invention of Writing

The first permanent settlement, Ur, was located in Ancient Mesopotamia (often called Cradle of Civilization). Mesopotamia (Figure 4.2) was formed in the fertile crescent between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is now Iraq. Once people began to stay in one place and developed agriculture, civilizations formed. The ability of a culture to express itself well, especially in writing, and to organize itself thoroughly, as a social, economic, and political entity, distinguishes it as a civilization. Civilizations have large population centers, monumental architecture or unique art, a state religion or ideology, a system for administering territories, a complex division of labor, social classes, and a system of recording information. A culture is a way of thinking and living established by a group of people and transmitted from one generation to the next. In other words, a culture is the basis of communal life. A culture’s values are expressed in its arts, writings, customs, and intellectual pursuits.

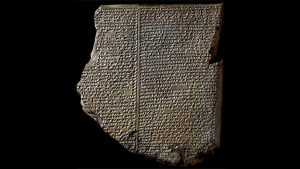

Eventually, four nations were established in Mesopotamia: Samaria, Sumer, Assyria, and Babylonia. It was the Sumerians who first developed writing in 3200 BCE. They recorded their histories and stories by carving Sumerian letters into giant tablets, a labor-intensive task. The older story ever written is the Epic of Gilgamesh (Figure 4.3), recorded 2750-2500 BCE. To give you a point of reference, the oldest record of the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Jewish Torah and the Christian Bible) is dated 1312-1280 BCE.

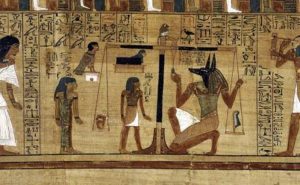

The invention of writing soon reached the Egyptians, one of the most sophisticated empires of this ancient time. They soon developed a written language of their own, and they developed a better way of recording their language as well. Papyrus was created by gathering the reeds that grew along the Nile, harvesting their fibers, and weaving these fibers together. This was similar to the process that the Egyptians used to make linen. However, papyrus was wetted and weighted down. When it was dry, it was thinner yet stiffer than linen. Papyrus was cut into sheets and rolled into scrolls. The Egyptians, however, did not write down their stories. Instead, they were meticulous record-keepers, preferring to record laws and rulings; marriages, births, and deaths; the amount of rainfall and grain harvested; and even pharmacological textbooks (Figure 4.4).

It was the Chinese who invented paper, which uses the pulp of a plant rather than the fibers. The oldest piece of paper was created in China around 179-41 BCE. The process of making paper that is very similar to what we still use today was invented by Cai Lun (Figure 4.5) of China’s Hun dynasty in 105 CE.

Focus on Folklore

The American Folklore Society describes folklore as “cultural DNA,” an apt metaphor. Folklore generally references the expressive arts, customs, and traditions shared by a culture or group of people. Click here to watch a great Prezi presentation on folklore.

Because this is a composition course, we will focus on folktales: narratives or stories passed down from one generation of a culture to another through an oral tradition. Because folktales are imbued with the rituals, beliefs, lifestyles, priorities, and language of a culture, we can learn much about cultures past and present by reading them. Hence, folklorists (those who study folklore) are basically a type of anthropologist.

Folklore exists in every culture from every time and every place. However, individual stories change as they move from place to place or generation to generation. These changes created different versions of the same story. The ability to create and tell stories is unique to humans as a species, and it plays an important role in our growth and survival. Folktales are traditionally told orally, from generation to generation, until eventually (sometimes hundreds of years later), they are written down. Folklore represents certain aspects of a culture, such as its ethics and social classes.

There are several types of folktales, such as fables, proverbs, mythology, fairy tales, and legends. Most of the fairy tales you have probably heard were likely collected by one of five people (pictured below).

Studying Folklore

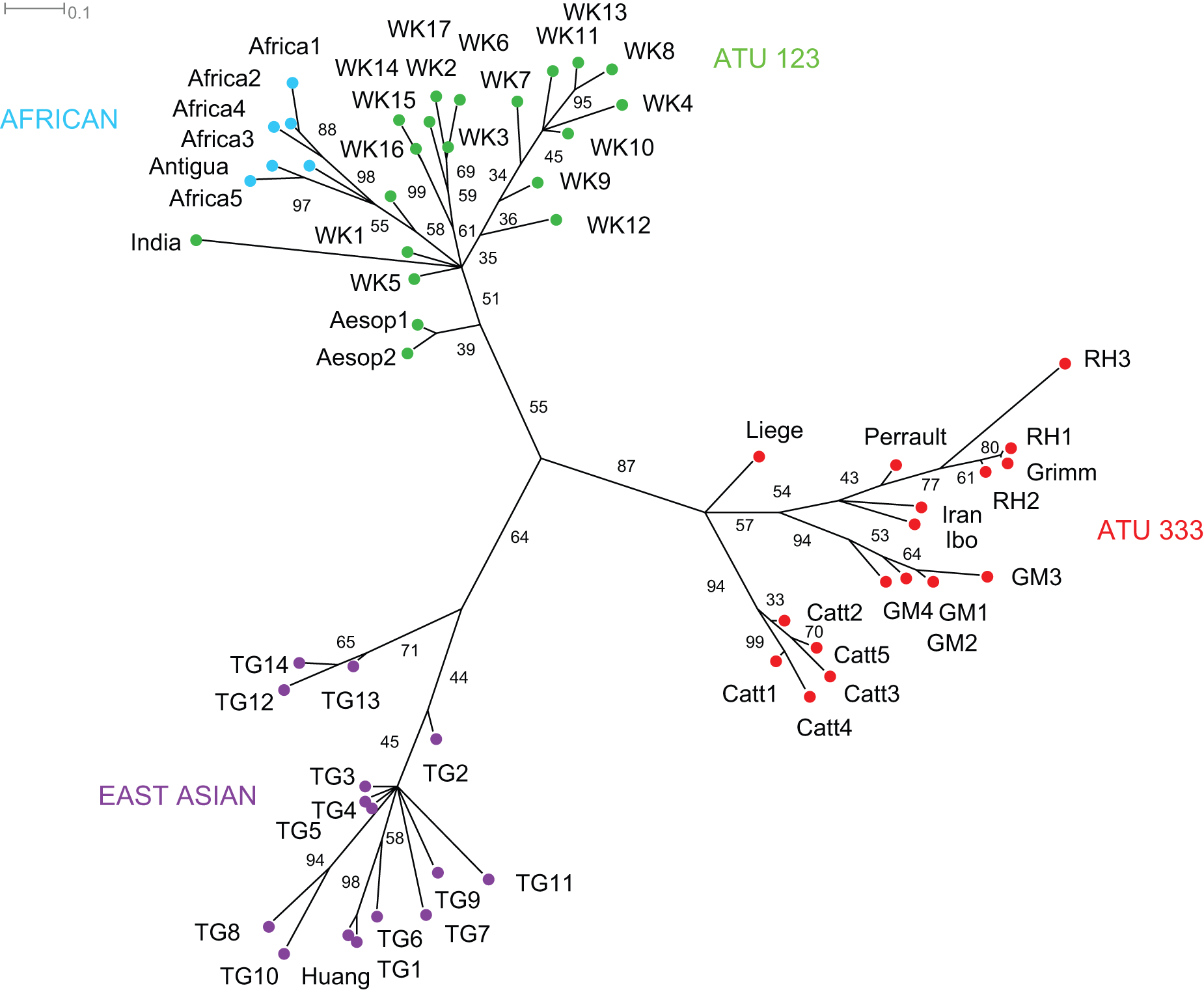

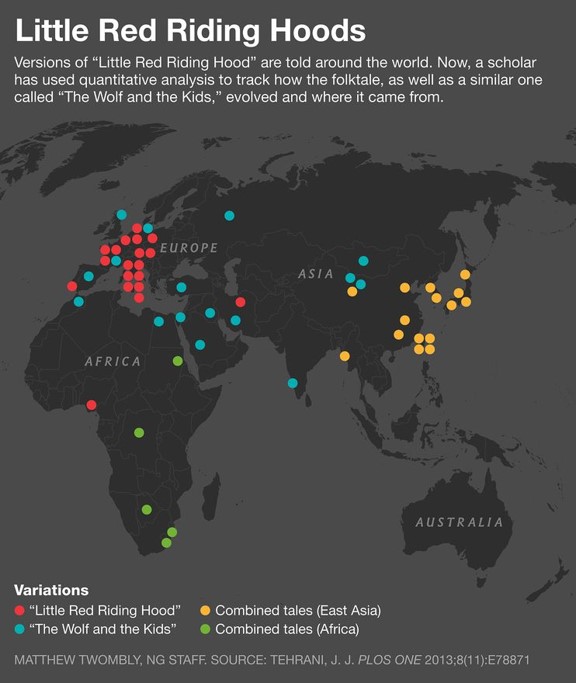

As mentioned earlier, as folk tales move from place to place and time to time, they evolve, creating different versions of the same story. To complicate matters, the same story may also develop different names in different languages (Figure 4.6). To better facilitate the study of these stories across languages, time periods, and cultures, we have assigned a series of numbers of letters to each individual story and its variations. This is called the Aarne-Thompson-Uther (ATU) system, named after the three people who invented it. For example, “Little Red Riding Hood” is labeled as ATU type 333. It is believed that “Little Red Riding Hood” stories evolved from another type of story, “The Wolf and the Kids” (ATU 123), which were the first stories featuring a “big bad wolf” as the villain. By looking at ATU 123 and 333 stories, Jamshid J. Tehrani (an anthropologist at Durham University) was able to chart Red Riding Hood’s family tree, showing how the story changed through time and place (Figure 4.7 and 4.8). Her study, “The Phylogeny of Little Red Riding Hood,” was published in PLOS One.

The ability of a culture to express itself well, especially in writing, and to organize itself thoroughly, as a social, economic, and political entity.

A way of thinking and living established by a group of people and transmitted from one generation to the next.

The traditional customs, tales, sayings, dances, or art forms preserved among a people.

A characteristically anonymous, timeless, and placeless tale circulated orally among a people.

A short story to teach a lesson, often with animals behaving as humans. Fables are usually meant for children. Examples: Mother Goose ("Humpty Dumpty") and Nursery Rhymes, Aesop's fables ("The Tortoise and the Hare").

Stories or sayings meant to impart truth or wisdom.

A system of stories that developed from religious beliefs. Worshippers of that religion believe their mythology to be true. Common mythological systems include Judeo-Christian-Islamic, Egyptian, Greco-Roman, Norse, and Celtic religions.

A type of folk tale that follows a "hero" as he or she defeats a "villain." While it does not always end happily, fairy tales do always impart a moral. Fairy tales include the use or magic or other supernatural elements.

The story of an historical figure that has been passed down and exaggerated (sometimes to supernatural proportions) over time.