27

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Invent the content of a rhetorical analysis. (GEO 1, 4; SLO 4)

- Organize and draft your rhetorical analysis. (GEO 2; SLO 1, 2)

- Create a specific style that is descriptive and easy to read. (GEO 1, 2; SLO 5)

- Develop a design with the use of visuals. (GEO 2; SLO 3)

If you have ever critiqued an advertisement or criticized the speech of a politician, you have done something similar to a rhetorical analysis. Rhetorical analyses are used to determine why some arguments work and others don’t. Advertisers, marketing analysts, and public relations agents use rhetorical analyses to understand how well their messages are influencing target audiences and the general public. Political scientists and consultants use rhetorical analyses to determine which ideas and strategies will be most persuasive to voters and consumers.

Ultimately, the objective of a rhetorical analysis is to show why a specific argument was effective or persuasive. By studying arguments closely, you can learn how writers and speakers sway others and how you can be more persuasive yourself.

In your college courses, you may be asked to analyze historical and present-day documents, advertisements, and speeches. These kinds of assignments are not always called “rhetorical analyses,” but any time you are asked to analyze a nonfiction text closely, you are probably going to write a rhetorical analysis.

In the workplace, your supervisors may ask you to closely critique your organization’s documents, Web sites, marketing materials, and public messaging to determine their effectiveness. Your ability to do a rhetorical analysis will help you to offer critical insights and suggestions for improvement.

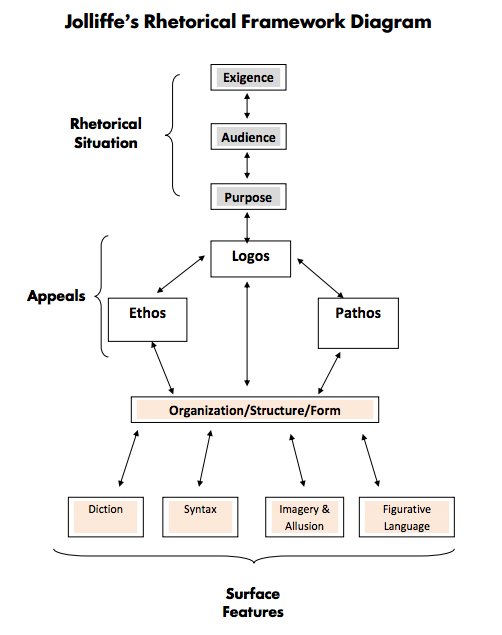

A variety of rhetorical analysis methods are available, such as metaphorical analysis, narrative analysis, pentadic analysis, genre analysis, and others. We cannot possibly discuss them all here. In this chapter, you will learn a popular method called “neo-Aristotelian” rhetorical analysis, which uses key concepts defined by the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle. David Jolliffe, the former chief reader of the Advanced Placement (AP) composition and literature exams, created a framework for analyzing these concepts (Fig. 27.1).

Inventing Your Rhetorical Analysis’s Content

When preparing to write a rhetorical analysis, the first thing you need to do is closely read the text you are analyzing. Read through it at least a couple of times, taking special note of any places where the author seems to make important points or perhaps misses an opportunity to do so.

Inquiring: Highlight Uses of Rhetorical Elements

In Chapter 17, you read about the five elements of the rhetorical situation. Instead of defining these elements for your own essay, in a rhetorical analysis, you will need to analyze how they are used in a piece of rhetoric written by someone else. The five elements of the rhetorical situation are topic, angle, context, audience, and purpose. However, if you look at the Jolliffe Rhetorical Analysis Framework (Fig. 27.1), you will see that only three of these elements are listed. The first two, topic and angle, are understood, so there is not a dedicated place for them in the framework. That leaves three elements for you to analyze: context, audience, and purpose.

Context

Context is anything beyond the specific words of a literary work that may be relevant to understanding the meaning. Contexts may be economic, artistic, social, cultural, political, historical, literary, biographical, or personal. When examining context, it’s important to ask: what about this society is necessary to know, in order to understand the rhetoric at play?

The specific type of context analyzed in the Jolliffe framework is exigence. Exigence is the specific problem, incident, or situation that caused the writer to create this message. Exigence is, in essence, the catalyst for the message itself. To determine, the exigence, ask: what prompted the creation of this message? Chances are, if the exigence did not exist, neither would the message.

Another type of context is kairos. Kairos is defined as the propitious moment for decision or action. Kairos is a type of context concerned with timing. When analyzing kairos, it’s important to ask: what made this moment in time the right, fitting, or opportune moment to communicate this message? The Ancient Greeks referred to kairos as the “supreme moment.” In a rhetorical analysis, we examine kairos in order to determine the larger context surrounding rhetoric.

Audience

There are two types of audience: intended and real. The intended audience (also called a target audience) is who the creator of message intends to reach, or who they are hoping will receive their message. The message is communicated with the intended audience in mind. On the other hand, the real audience is the actual group of people who receive a message. Sometimes, the intended audience and real audience are the same. However, not all messages reach their target audience. Messages may reach a larger or smaller audience that intended. We measure audience in terms of demographics, which are ways of organizing or categorizing people. Sorting people into these groups helps understand who the intended and real audiences are.

When it comes to rhetoric, success is determined by how close a message is to reaching its intended audience. If the real audience is roughly the same or larger than the intended audience, then the rhetoric was successful. If the real audience is smaller than the intended audience, then the rhetoric was not successful at communicating its message. It’s also important to ask why a message was successful or unsuccessful in reaching its audience.

Another factor we analyze when looking at rhetoric is effectiveness. Effectiveness is gauged by how the audience responded to the message. If an audience had a negative response to a message or no response at all, then the rhetoric was not effective. However, if the audience did respond, and they did so positively, then the rhetoric was effective. When it comes to rhetoric that is trying to sell a product or service, it’s easy to look for the audience’s response through sales figures. However, all rhetoric is more concerned with convincing its audience to believe its ideas (moreso than purchase a product or service). It is harder to tell if a rhetoric has convinced its audience to believe its message, but this can be accomplished through focus groups and internet soundboards.

Purpose

All messages are formed with a purpose in mind. The creator of a message has a specific goal they want to accomplish through their rhetoric. The audience is a key factor in accomplishing this goal. While all rhetoric is created to persuade, purposes are more complex than that. Consider what, exactly, the message is trying to persuade the audience to do or to think. Remember, while some rhetoric is trying to sell a product or service, ALL rhetoric is trying to sell an idea. Don’t just ask “What is this rhetoric trying to convince people to do/buy?” but “What is this rhetoric trying to convince people to BELIEVE?”

Inquiring: Highlight Uses of Proofs

Now, it’s time to do some analysis. When looking closely at the text, you will notice that authors tend to use three kinds of proofs to persuade you:

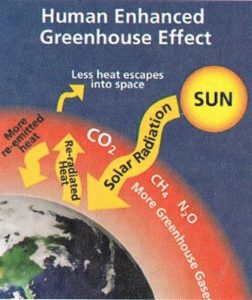

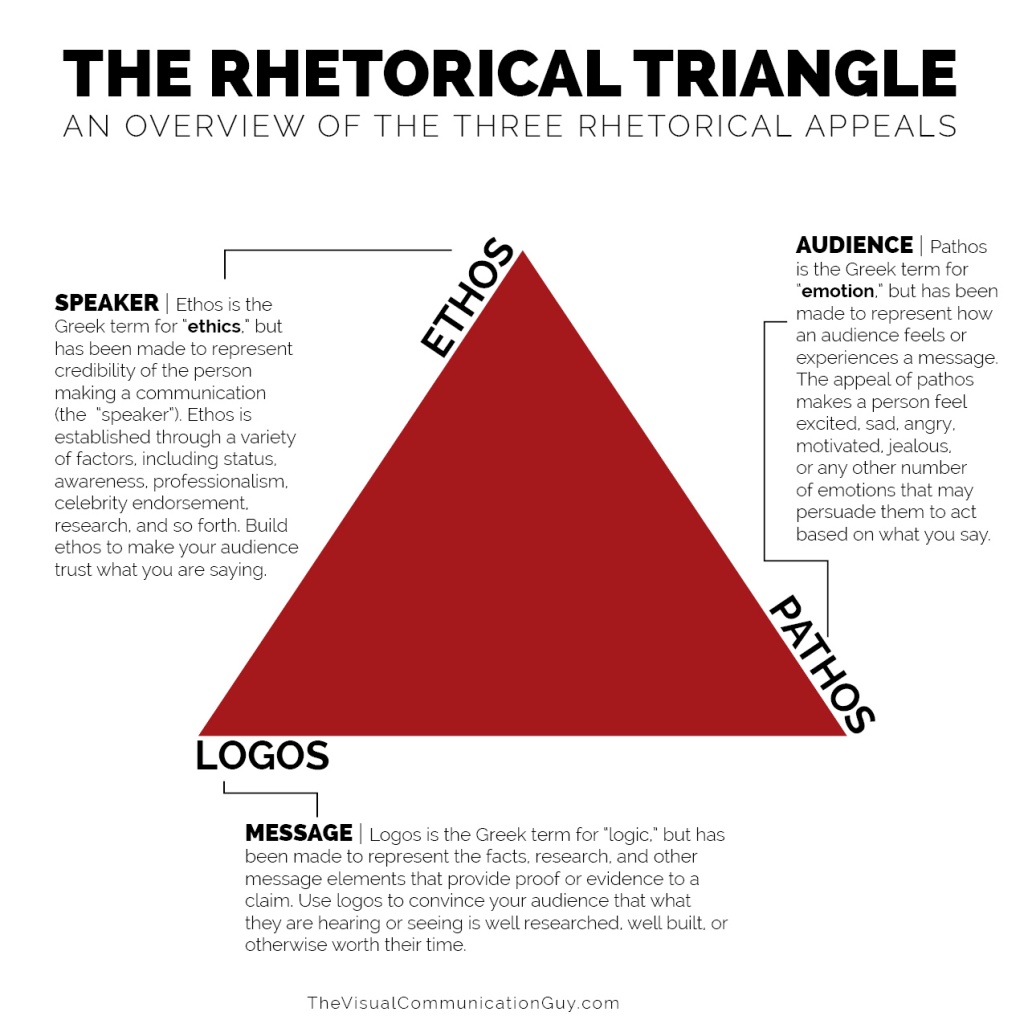

- Logos (Reasoning) (logos): appealing to readers’ common sense, beliefs, or values

- Ethos (Credibility) (ethos): using the reputation, experience, and values of the author or an expert to support claims

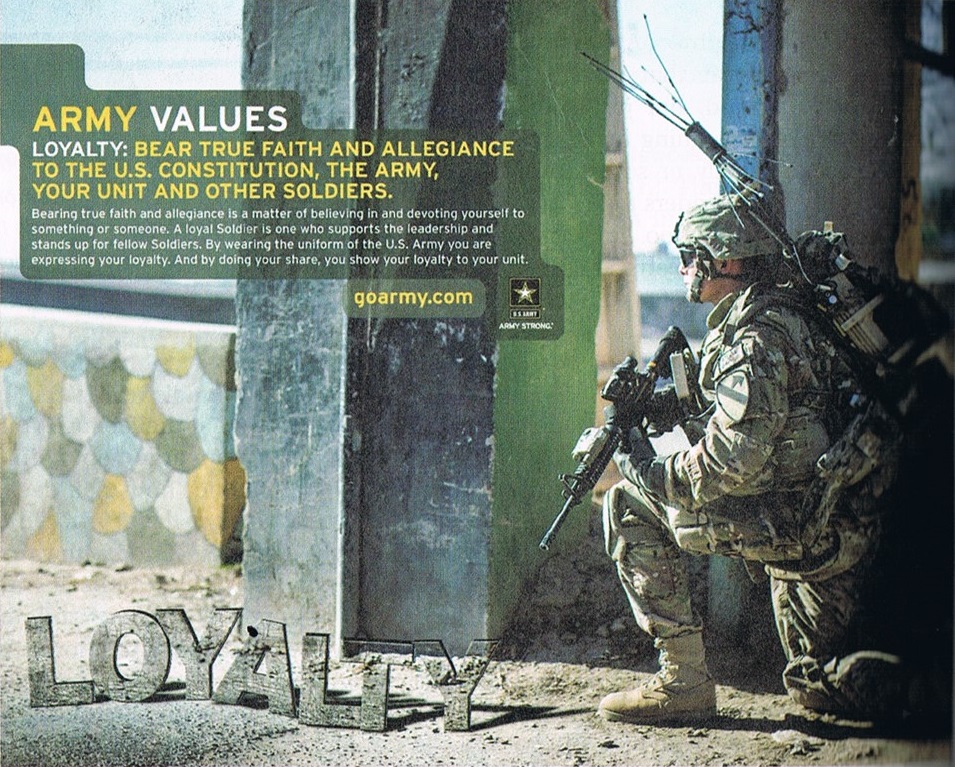

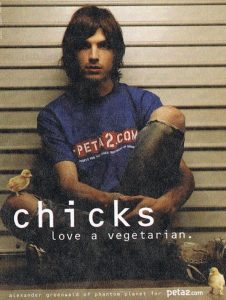

- Pathos (Emotion) (pathos): using feelings, desires, or fears to influence readers (Figure 27.2)

Rhetoricians often use the ancient Greek terms logos, ethos, and pathos to discuss these three kinds of proofs, so we have used them here. Let’s look at these concepts more closely.

Logos

Logos highlights uses of reasoning. The word logos in ancient Greek means “reasoning” in English. This word is the basis for the English word, logic, but logos involves more than using logic to prove a point. Logos also involves appealing to some-one else’s common sense and using examples to demonstrate a point (Fig. 27.3). As you analyze the text, highlight these uses of reasoning so you can figure out how the writer uses logos to influence people.

Ethos

Ethos highlights uses of credibility. The Greek word ethos means “credibility,” “authority,” or “character” in English. It’s also the basis for the English word, ethics. Ethos could refer to the author’s credibility or to the use of someone else’s credibility to support an argument (Figure 27.4).

Highlight places in the text where the author is using his or her authority or credibility to prove a point. When you are searching for ethos-related proofs, look carefully for places where the author is trying to use his or her character, expertise, or experience to sway readers’ opinions.

Pathos

Pathos highlights uses of emotion. Finally, look for places where the author is trying to use pathos, or emotions, to influence readers (Fig. 27.5). As you analyze the text, highlight places where the author is using these basic emotions to persuade readers.

The psychologist Robert Plutchik suggests there are eight basic emotions: joy, acceptance, fear, surprise, sadness, disgust, anger, and anticipation. Some other common emotions that you might find are annoyance, awe, calmness, confidence, courage, delight, disappointment, embarrassment, envy, frustration, gladness, grief, happiness, hate, hope, horror, humility, impatience, inspiration, jealousy, joy, loneliness, love, lust, nervousness, nostalgia, paranoia, peace, pity, pride, rage, regret, resentment, shame, shock, sorrow, suffering, thrill, vulnerability, worry, and yearning.

Frequently, writers will not state emotions directly. Instead, they will inject feelings by using emotional stories about others or by incorporating images that illustrate the feelings they are trying to invoke. Advertisements, for example, rely heavily on emotions to influence viewers.

You can read more about each of these proofs in Chapter 8: Argumentative Strategies.

These three appeals come together to create the rhetorical triangle (Fig. 27.6). Each proof has a different source within the rhetoric. Logos comes from the words of the message, ethos comes from the speaker of the message (or the creator if there is no speaker), and pathos comes from the audience.

Researching: Finding Background Information

Once you have highlighted the proofs (i.e., logos, ethos, pathos) in the text, it’s time to do some background research on the author, the text, and the context in which the work was written and used.

- Online sources. Using Internet search engines and electronic databases, find out as much as you can about the person or organization that created the text and any issues that he, she, or they were responding to. What historical events led up to the writing of the text? What happened after the text was released to the public? What have other people said about it?

- Print sources. Using your library’s catalog and article databases, dig deeper to understand the historical context of the text you are studying. How did historical events or pressures influence the author and the text? Did the author need to adjust the text in a special way to fit the audience? Was the author or organization that published the text trying to achieve particular goals or make a statement of some kind?

- Empirical sources. In person or through e-mail, you might interview an expert who knows something about the author or the context of the text you are analyzing. An expert can help you gain a deeper understanding of the issues and people involved in the text. You might also show the text to others and note their reactions to it. You can use surveys or informal focus groups to see how people respond to the text.

Organizing and Drafting Your Rhetorical Analysis

At this point, you should be ready to start drafting your rhetorical analysis. As mentioned earlier, rhetorical analyses can follow a variety of organizational patterns, but those shown in the At-A-Glance section are good models to follow. You can modify these patterns where necessary as you draft your ideas.

Keep in mind that you don’t actually need to use rhetorical terms such as logos, ethos, and pathos in your rhetorical analysis, especially if your readers don’t know what these terms mean. Instead, you can use words like “reasoning,” “credibility,” and “emotion,” which will be more familiar to your readers.

The Introduction

Usually, the introduction to a rhetorical analysis is somewhat brief. In this part of your analysis, you want to make some or all of these moves:

Identify the subject of your analysis and offer background information. Clearly state what you are analyzing and provide some historical or other background information that will familiarize your readers with it. To give your readers an overall understanding of the text you are analyzing, provide them with some historical background on it. Tell them who wrote it and where and when it appeared. Then summarize the text for them, following the organization of the text and highlighting its major points and features.

The aim of this historical context section is to give your readers enough background to understand the text you are analyzing. For example, here is the historical context and a summary of an anti-smoking campaign called “The Real Cost”:

Example

The Real Cost campaign was created in 2014 by an advertising firm called Draftfcb for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (AdWeek 2014). The campaign focuses on the “costs” of smoking to a person’s health. Each ad stresses the effects of smoking on teeth and skin, showing teens how smoking today will cause their teeth to turn brown and their skin to wrinkle. Most of the advertisements like the one shown in Fig. 1 use altered images of teens in startling ways.

This ad seems to follow the typical path, showing a girl with browned teeth due to smoking. People who come across these side-by-side images are immediately struck by the differences between the attractive girl on the left and the much less attractive girl on the right. The written text on the left says, “See what your SMILE COULD LOOK LIKE . . .” and on the right it says, “. . . if you SMOKE.” Then, the small print explains the possible consequences of smoking, like yellow teeth, gum disease, and tooth loss.

The length of your summary depends on your readers. If they are already familiar with the text you are analyzing, your summary should be brief. You don’t want to bore readers by telling them something they already know. If, however, they are not familiar with the text, your summary should be longer and more detailed.

State the purpose of your analysis. Explain that the purpose of your analysis is to determine whether or not your subject was effective or persuasive.

State your main point or thesis. Rhetorical analyses are generally used in academic settings, so they often include a clear main point or thesis statement in the introduction. Here are examples of a weak thesis statement and a stronger one:

Examples

Weak: The advertisements for Buffalo Wild Wings are effective because they are funny.

Stronger: Buffalo Wild Wings’ “The Official Hangout of March Madness” campaign is successful because it humorously shows that B-Dubs is a place where funny, unexpected, and even magical things happen to the young people who are there.

Stress the importance of the text. Tell readers why your subject’s rhetorical strategies are interesting or worth paying attention to.

Analysis of the Text

Now it is time to analyze the text for your readers. Essentially, you are going to interpret the text for them, using the rhetorical concepts you defined earlier in the rhetorical analysis. You should discuss the text through each rhetorical concept separately, analyzing the uses of logos, ethos, and pathos to discuss the text’s use of each kind of proof.

For example, here is a discussion of pathos in “The Real Cost Campaign”:

Example

Using Emotions in a Unique Way

At first glance, “The Real Cost” ad doesn’t seem to be doing anything new, but there is something more subtle and powerful going on. Like other anti-smoking messages, it is using emotional arguments (pathos) to scare teens into not smoking. Ads like this one target the main thing that teens, especially “cool” teens, care about—their looks. Teens want to be like the girl in the left picture. She looks pretty and fun with perfect teeth and a gleam in her eyes. She could be your best friend, captain of the volleyball team, and a fashion model at the same time. Even guys identify with her because she’s the kind of girl they would want to hang out with or even date. She looks healthy and happy.

The same girl on the right sends a completely different emotional message. This picture is basically the same, but now the girl’s yellow-brown teeth make her almost ugly. That gleam in her eye is gone. Even weirder, though, she doesn’t look fun anymore, and she doesn’t look healthy or happy. She seems to be faking that she is happy. The girl on the right actually seems unsatisfied with herself and even sad. Not only is this girl much less attractive, but she looks like she is hiding something. This use of pathos powerfully taps into teens’ inner anxieties that they will be exposed as fakers or that other people will see through them in some way. For many people, but especially females, there is a “terror of being unmasked as an imposter” (Roche and Whitacre 4). This ad hints that smoking reveals that a person is really not as happy or healthy underneath as they or others would like to believe.

In this discussion of emotion, the writer is applying her definition of pathos to the campaign. This allows her to explain how the use of emotion can deter teens from smoking. She then goes on to discuss the use of logos and ethos in the ad.

The Conclusion

When you have finished your analysis, it’s time to wrap up your argument. Keep this part of your rhetorical analysis brief. A paragraph or two should be enough. You should answer one or more of the following questions:

- Ultimately, what does your rhetorical analysis reveal about the text you studied?

- What does your analysis tell your readers about the rhetorical concept(s) you used to analyze the text?

- Why is your explanation of the text or the rhetorical concept(s) important to your readers?

- What should readers look for in the future when faced with this kind of text or this persuasion strategy?

Minimally, the key to a good conclusion is to restate your main point (thesis statement) about the text you analyzed.

Choosing an Appropriate Style

The style of a rhetorical analysis depends on your readers and where your analysis might appear. If you are writing your analysis for an online magazine like Slate or Salon, readers would expect you to write something colorful and witty. If you are writing the argument for an academic journal, your tone would need to be more formal. Here are some of the stylistic choices you’ll need to make while creating a rhetorical analysis that is engaging and informative for your readers:

Use lots of detail to describe the text.

In detail, explain the who, what, where, when, why, and how of the text you are analyzing. You want readers to experience the text, even if they haven’t seen or read it themselves.

Minimize the jargon and difficult words.

Unnecessary use of specialized terminology and complex words will make your text harder to read.

Improve the flow of your sentences.

Rhetorical analyses are designed to explain a text as clearly as possible, so you want your writing to flow easily from one sentence to the next. The best way to create this kind of flow is to use the “given-new” strategies that are discussed in Chapter 12: Body Paragraphs. Given-new involves making sure the beginning of each sentence uses something like a word, phrase, or idea from the previous sentence.

Pay attention to sentence length.

If you are writing a lively or witty analysis, you will want to use shorter sentences to make your argument feel more active and fast-paced. If you are writing for an academic audience, longer sentences will make your analysis sound more formal and proper. Keep in mind that your sentences should be “breathing length,” neither too long nor too short.

Designing Your Rhetorical Analysis

Computers make it possible to use visuals in a rhetorical analysis. Here are some things you might try:

Download images from the internet.

If you are reviewing a book or a historical document, you can download an image of it to include in your rhetorical analysis. This way, readers can actually see what you are talking about.

Add a screenshot.

If you are writing about an advertisement from the Internet, you can take a picture of your screen (i.e., a screenshot). Then you can include that screenshot in your analysis.

Include a link to a podcast.

If you are analyzing a video or audio text (perhaps something you found on YouTube), you can put a link to that text in your analysis. Or you can include the Web address so readers can find the text themselves. If your analysis will appear online, you can use a link to insert the podcast right into your document. Why not be creative? Look for ways to use technology to let your readers access the text you are analyzing.

Microgenre: The Ad Critique

An ad critique evaluates an advertisement to show why it is or is not effective. If the ad is persuasive, show the readers why it works. You can also use an ad critique to explain why you like or dislike a particular type of advertisement. You should aim your critique at people like you who are consumers of mass media and products. Today, ad critiques are becoming common on the Internet, especially on blogs. They give people a way to express their reactions to the many kinds of advertisements bombarding them. Here are some strategies for writing an ad critique:

Summarize the ad.

If the ad appeared on television or the Internet, describe it objectively in one paragraph. Tell your readers the who, what, where, and when of the ad. If the ad appeared in a magazine or other print medium, you can scan it or download the image from the sponsor’s Web site and insert the image into your document.

Highlight the unique quality that makes the advertisement stand out.

There must be something remarkable about the ad that caught your attention. What was it? What made it stand out from all the other ads that are similar to it?

Describe the typical features of ads like this one.

Identify the three to five common features that are usually found in this type of advertisement. You can use examples of other ads to explain how a typical ad would look or sound.

Show how this ad is different from the others.

Compare the features of the ad to those of similar advertisements. Demonstrate why this ad is better or worse than its competitors.

Include many details.

Throughout your critique, use plenty of detail to help your readers visualize or hear the ad. You want to replicate the experience of seeing or hearing it.

Why I Love H&M’s Latest Ad by Sam Parker

The latest advertisement for H&M’s autumn collection reinvents the term “relatable.” The video, which rolls to Lion Babe’s remixed tune of “She’s a Lady” by Tom Jones, captures an idea and makes a statement. The idea is that women are no longer described by archaic beliefs of how a lady should act.

Starring actress Lauren Hutton, model Adwoa Aboah, and Lion Babe’s Jillian Hervey, among others, the video propagates the boundless, free expression of women. In so many words, this ad exclaims that being a lady is simply done however a woman chooses to do it.

While one woman picks at her teeth in a restaurant using her knife as a mirror (Figure 27.7), another leads a business meeting (Figure 27.8). Following that is a woman who unzips her jeans to allow more room for French fry induced bloating, and another sits freely on a bus with her knees widespread.

This ad is so powerful because of the way each woman is doing what she chooses to do, not what society wants her to. It tackles social concepts of beauty and womanhood by making subtle remarks about things like armpit hair and buzzcuts for women. It shows an organic expression of women that pays no attention to the outdated rules for behaving “properly” and instead allows them to play by their own rules.

This ad sifts through various representations of being a lady today, leaving its audience with at least one depiction that they can relate to. That is exactly what makes this advertisement so brilliant.By creating this ad, H&M is issuing a public stance regarding their customers and women everywhere. The modern clothing brand isn’t just showing a variety of behaviors; it is essentially calling out the social boundaries that women face. There’s no room for rules or regulations; there’s only room for freedom of expression. That is what this ad says to me.

This ad is one that any woman can find comfort in watching. By representing the limit-less concept of being a lady, the brand is showing itself as one that emboldens women to shine through whatever means are necessary to them. That concept is what women are seeking today, and H&M has lit a celebratory torch for it by creating this advertisement.

The women featured in this video are no different from you and me, except that they can expose exactly who they are in a space that is free from judgment or ridicule. That space is what I think H&M is advocating for and what they intend to support with their customers.

Rhetorical Analysis Example #1: “Nike, Colin Kaepernick, and the History of ‘Commodity Activism’” by Sarah Banet-Weiser (Vox 7 September 2018)

Nike’s Kaepernick Ad Continues – And Tweaks – The Tradition of Brands Commodifying Politics

It didn’t take long for the internet to explode when Nike announced who would be the new face of its brand.

On Labor Day, Nike tweeted a photo of NFL player Colin Kaepernick, (in)famous for sparking controversy when he took a knee during the national anthem to protest police brutality, to celebrate the corporation’s 30th anniversary of the slogan “Just Do It.” The image — Nike’s usual stark, intense black-and-white style — features Kaepernick staring directly at the camera overlaid by the text, “Believe in something. Even if it means sacrificing everything. Just Do It.”

The ad garnered significant response on social media. Many applauded Nike’s embrace of such an openly political figure. Some on the right were livid that the brand endorsed someone who, to them, represents a lack of loyalty to American values. Others on the left were indignant about the ways protest and resistance were being commodified and used to build a behemoth company’s brand. And some were just happy that Kaepernick, who has yet to be signed to an NFL team since his contract expired in 2016, has any kind of job at all.

Rather than wade through this debate, I’d like to offer a more broadly contextual analysis of Nike’s latest campaign, situating it within a long history of what Roopali Mukherjee — a professor at CUNY Queens College with whom I co-wrote a book on this subject — and I have called “commodity activism.”

This practice merges consumer behavior with political or social goals. Whether challenging police brutality or questioning unattainable beauty norms, branding in our era has extended beyond a business model: It is now both reliant on and reflective of our most basic social and cultural relations. The use of brands to “sell” dissent is not a new business strategy. Individual consumers act politically by purchasing particular brands over others in a competitive marketplace, where specific brands are attached to political aims and goals.

Nike Has A History Of Using Political Movements In Its Ads

There are ample examples of commodity activism. In 2008, Starbucks began offering “fair trade” coffee that pledged to pay producers in developing countries a fair wage. Gap joined several other companies to form RED, a philanthropic organization dedicated to fighting AIDS in Africa, in 2006. In 2011, Chrysler used the context of global economic collapse and the failing automobile industry to build its brand and advocate for more consumption as a way to overcome crisis; the ad featured Detroit rapper Eminem.

Nike’s latest effort to connect its brand with a political project is certainly not its first. In 1992, the company created one of the first “girl empowerment” ad campaigns, one that specifically positioned sports as a route to empowerment for girls and women. The campaign, “If You Let Me Play,” created before hashtags existed, first appeared as a print ad. With this campaign, Nike launched one of the first corporate efforts to sell its products alongside self-confidence, strength, and empowerment for girls and women.

Dozens of companies followed its lead. Dove’s widely successful “Real Beauty” campaign is just one of dozens of examples of companies following Nike’s lead in selling female confidence and empowerment as part of their shampoo, cereal, or yoga pants brand. At this point in contemporary culture, it is utterly unsurprising to “participate” in social activism by buying something.

But not all politics is equally “brandable.” Female empowerment, fighting AIDS in Africa, building homes for people left homeless after national disasters — those are fairly uncontroversial politics for brands to partner with. Even when brands harness politics to sell their products, they don’t want to alienate too much of their consumer base. After all, they still want to sell products.

But race and racial tension — especially in the context of continued violence against people of color in the United States, an issue on which the public is deeply divided — are not quite as easy to simply commodify and brand. For example, in 2017, when Pepsi decided to create an ad using Kendall Jenner, a 21-year-old white reality television star and brand influencer, to advocate for “a global message of unity, peace, and understanding” between police officers and the Black Lives Matter movement, it was an epic failure.

Pepsi’s incredibly tone-deaf ad, which minimized the urgency of the Black Lives Matter movement, diminishing it as a happy peaceful gathering where people are most interested in drinking soda, is an example of how not to connect brands with politics. Pepsi pulled the ad only days after it aired.

Nike’s Partnership With Kaepernick Is Riskier Than Its Previous Politically Motivated Campaigns

The Nike Kaepernick ad campaign also treads on risky ground, given the public outrage that Kaepernick has faced for his political stance against racial violence in the US — not to mention that Nike’s own history with questionable labor practices hardly makes it a progressive bastion.

But unlike Pepsi, Nike has a history of connecting with politics as part of its branding, and while the company is not uncontroversial, openly advocating for political stances hasn’t ruined the brand. Brand culture creates a context within which consumer participation is not simply (or even most importantly) indicated by purchases, but by brand loyalty and affiliation, linking brands to lifestyles, politics, and social activism.

Nike knew what it was doing when it decided to sponsor Kaepernick; it knew perfectly well that the ad would enrage some consumers who have been vocal about their anger around NFL players kneeling in protest. Nike also knew that the campaign would further solidify it as a socially progressive company, which is important for many of its younger consumers, who skew liberal and represent the company’s future customers.

The proliferation of commodity activism such as Nike’s, in other words, serves as a trenchant reminder that there is no “outside” to the logic of contemporary capitalism; social action may itself be shifting shape into a marketable commodity. We may, on the one hand, characterize Nike’s most recent “Just Do It” campaign as yet another corporate appropriation, an elaborate exercise in hypocrisy and artifice intended to fool the consumer and secure ever-larger profits.

On the other hand, Kaepernick’s ad, and the message he offers, may also illuminate the promise of innovative creative forms, including advertising. His role in the Nike partnership might be a cultural intervention that we need right now — it allows us to think critically about modes of dominance and resistance within changing social, cultural, and political landscapes.

UPDATE: “Nike’s Colin Kaepernick Ad Sparked A Boycott — And Earned $6 Billion For Nike” By Alex Abad-Santos (Vox 24 September 2018)

The Kaepernick “Gamble” Has Turned Into A Big Win

The boycott against Nike for making Colin Kaepernick the face of its latest ad campaign doesn’t seem to be having the desired effect.

According to CBS, Nike’s stock has soared over the past year, seeing a 5 percent increase since Labor Day — the day it revealed that Kaepernick, the former quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers, was the star of company’s 30th-anniversary “Just Do It” campaign.

Kaepernick appeared in a TV spot and a print ad championing a riff on the Nike slogan: “Believe in something. Even if it means sacrificing everything. Just Do It.” The sacrifice in question is a reference to Kaepernick’s kneeling protests against police brutality before NFL games. (Kaepernick is currently suing the NFL for allegedly colluding to keep him out of the league over the protests.)

Though Kaepernick and other NFL players who have kneeled during the national anthem before NFL games have maintained that their protest is about police brutality resulting in the deaths of unarmed black Americans, that hasn’t stopped their critics — including President Donald Trump — from claiming that Kaepernick and his colleagues are disrespecting the American flag.

In response to Nike’s decision to center its campaign — which also features stars like Serena Williams and LeBron James — on Kaepernick, some people have decided to boycott the company. In some cases, those people have performatively destroyed their Nike gear on social media. But the $6 billion increase in overall value that Nike has experienced since Labor Day clearly overshadows their efforts (though to be clear, the US Open — which concluded about a week after the ad was released — and the official start of the NFL season have been known to drive Nike sales too).

Though the country is divided over Kaepernick’s protests — both by race and by partisanship, according to an NBC/WSJ poll in August — Kaepernick is still a merchandise-selling machine. Sales of jerseys bearing his name have been among the league’s most popular even though he hasn’t played in two years, and Reuters reported last week that Nike’s Kaepernick women’s jersey had sold out.

With its post-Labor Day payout, Nike’s choice to build its brand around Kaepernick, what he stands for, and all the politics that come with it looks less and less like a risk and more like a surefire win.

Rhetorical Analysis Example #2: “This Powerful Bodyform Commercial Is All About Blood” by Alexandra Jardine (Ad Age 27 May 2016)

Campaign Aims To Break ‘Last Taboo’ In Sport

Women bleed, but it doesn’t stop them competing, in this U.K. commercial from Bodyform, part of a campaign by the feminine hygiene brand that aims to break down taboos around the menstrual cycle and exercise.

Directed by Stink’s Jones + Tino for AMV BBDO, the ad portrays women taking part in sport from surfing to ballet, with gashed faces, bleeding noses, raw and bloody toes, scraped hands and more. In its uncompromising and authentic portrayal of women, it’s reminiscent of Sport England’s award-winning “This Girl Can” commercial — but more hardcore, and with injuries. The ad ends with the tagline “No blood should hold us back.”

The wider campaign, titled Red.Fit, aims to enable women to become more mentally and physically motivated throughout their menstrual cycle. Bodyform has entered into a research partnership with St. Mary’s University, Twickenham and University College London (UCL) investing in a PhD program exploring the effect of the menstrual cycle on women’s health and exercise.

An online hub will provide consumers with direct access to the research findings, together with exercise videos, nutritional information and motivational podcasts for different phases of their menstrual cycle.

Nicola Coronado, marketing director at SCA-owned Bodyform, said in a statement: “Menstruation really is “the last taboo” for women in sport, simply because we lack knowledge and understanding of this subject area. Using our partnership with St. Mary’s University, Twickenham and UCL will help us to challenge these category stereotypes and transform the consumer mindset when it comes to the perceived barriers around periods and exercise.”

The campaign comes as other feminine hygiene brands are trying to disrupt the category — in particular HelloFlo, which brought comedy to periods.

Rhetorical Analysis Example #3: “The Greatest Ad I’ve Ever Seen” by Seth Stevenson (Slate 6 June 2010)

Nike’s Epic, Witty, Wonderful New World Cup Ad

The Spot: Soccer stars imagine the alternate universes they might create with their play—good or bad—in the upcoming World Cup. Will they be winners or losers? Heroes or goats? Adored celebrities or shunned trailer park shut-ins? It can all hang on a single kick of the ball. As the spot closes, the words “Write the Future” appear above the familiar Nike swoosh.

In 1994, when the World Cup first arrived on American soil, Nike’s soccer division brought in $40 million in annual revenue. This year, the figure is $1.7 billion. Together with subsidiary label Umbro, Nike is now the No. 1 soccer brand on the planet. Which is astonishing, given that 1) it’s an American company, and Americans still aren’t fully on board with this frou-frou soccer stuff; 2) Adidas, its major rival in the category, had been synonymous with big-time futbol for decades—long before swoosh-emblazoned soccer cleats were even a gleam in Phil Knight’s eye.

How did Nike eat Adidas’ home-cooked lunch? It wasn’t by manufacturing better cleats. It was by manufacturing a better image. The fact that a jogging-shoe company from Oregon could establish itself as the world’s dominant soccer brand is the ultimate testament to the power of shrewd, relentless marketing.

Nike clawed its way to the top by employing its gushing cash flow (which stems, in part, from the brand’s 85 percent share of the U.S. market for basketball footwear) to sign expensive endorsement contracts with a slew of major soccer stars. In 2007, Nike bought Umbro—official maker of the England national squad’s uniforms—for roughly $580 million. And now comes this monumental three-minute ad, which is without doubt the most expensive soccer commercial ever made.

It’s also the most entertaining soccer commercial ever made. Helmed by Academy Award-nominated director Alejandro González Iñárritu, the spot is a frenzy of quick-cut, hyperspeed storytelling. Like Iñárritu’s movies (Babel, 21 Grams, Amores Perros), the ad jumps lithely among multiple plotlines. * But while Iñárritu’s feature films often substitute temporal disorientation for a well-devised narrative, and soapy melodrama for gravitas, here the bouncy mood and compacted running time are a perfect match for the director’s over-the-top impulses.

We begin with what appears to be a standard big-budget soccer spot. Ivory Coast star Didier Drogba charges up the field, making a few nifty moves in slow motion before unleashing a shot that appears destined for the back of the net. At the last moment, Italian defender Fabio Cannavaro bicycles the ball away, preventing a goal. The famous athletes, the high stakes, the cranked-up cinematography—to this point, it could easily be another snoozy, big-budget Adidas ad. But then the spot takes a left turn: We cut to Bobby Solo, the Elvis of Italy, crooning an ode to Cannavaro’s exploits while sequined dancing girls re-create the balletic kick on a TV variety show.

From here on, the ad offers a series of richly imagined realities. In the funniest of these, English star Wayne Rooney envisions two divergent futures. When Rooney makes a bad pass that gets intercepted, it triggers a downward spiral that concludes with him living in a trailer park, bearded and fat, eating beans from a pot and earning his living as a groundskeeper for a minor league soccer team. When he recovers the ball, his fortunes reverse—the FTSE soars, he’s knighted by the queen, and he calmly whups Roger Federer in a game of table tennis.

The whole spot is packed to its seams with inventive wit and dazzling cameos. When Ronaldinho jukes an opponent with a stutter-step jig, we watch a clip of the move rack up YouTube views, become the basis of a “Samba-robics” exercise video, and get paid tribute by Kobe Bryant as he celebrates a game-winning jumper. Later, Cristiano Ronaldo fantasizes that a successful World Cup will land him an appearance on The Simpsons (he nutmegs Homer, who exclaims, “Ronal-d’oh!”) and make him the subject of a blockbuster biopic starring Gael García Bernal.

Only Nike has the juice to throw together this sort of multi-sphere star power and then buff the production values to such a glitzy sheen. The ad took a year of creative gestation from Nike’s genius ad agency, Wieden + Kennedy, followed by three months of camerawork and editing. It was filmed in locations including England, Spain, Italy, and Kenya. While Nike won’t disclose its budget, I would not be surprised if the cost to make this three-minute spot was on par with the outlay for at least one or two of Iñárritu’s feature-length films.

And yet the joy is entirely in the small details. Rooney’s ginger nest of a beard. Or his tuxedoed ping-pong interlude in a wood-paneled rec room. English fans will instantly recognize that the billboard hanging above Rooney’s squalid trailer, cruelly taunting him (it’s a photo of French star Franck Ribery, with the Tricolour flag painted on his naked chest and arms) is a clever parody of an actual, well-known Rooney billboard in which the Brit posed with the St. George cross splashed across his pecs. Even non-soccer fans, who may not catch all the references, will deduce that loving care was poured into each frame of these 180 seconds.

According to Nike, the ad has notched 12 million YouTube views so far and another 17 million views on other Web platforms. It has aired in its entirety on TVs in more than 30 countries, and has appeared at least a couple of times on ESPN here in the States. The multiple storylines will allow for a jumble of re-edited 60-, 30-, and 15-second versions, which will pop up throughout World Cup broadcasts.

Perhaps longer ads have been made. Perhaps more expensive ads have been made. But when this spot first showed up on my TV, as I was watching SportsCenter late one night, I thought to myself that I couldn’t remember having ever derived more exhilarating joy from a TV commercial.

Grade: A+. I even love the soundtrack, a remix of a yodel-infused instrumental rock tune called “Hocus Pocus,” by Dutch band Focus. It’s unfortunate that a couple of the featured players may not actually appear in the World Cup–Drogba was recently injured and his participation is still in doubt, while Ronaldinho got cut from the Brazilian team—but these are the vagaries of big-time soccer. It’s also unfortunate (for fans of great ads) that Nike didn’t air this spot during February’s Super Bowl, which lacked in the epic advertising grandeur we crave from the NFL’s big game. Maybe it was too soon to begin ramping up the World Cup hype. Maybe it was too costly to buy three minutes of Super Bowl airtime. Or maybe Nike worried that America couldn’t endure the shame of watching futbol out-glam football.

Rhetorical Analysis Example #4: “Rhetorical Analysis of the ‘Keep America Beautiful’ Public Service Announcement (1971)” by Wes Rodenburg (Writing Today 2010)

The original Keep American Beautiful public service announcement (PSA) aired for the first time on Earth Day in 1971, and it is widely credited for inspiring environmental consciousness and changing minds about pollution. The commercial features Iron Eyes Cody, a movie actor who has since become an icon of the environmental movement. At the beginning of the PSA, Iron Eyes paddles his birch bark canoe down an American river. The river is natural and clean at the beginning, but as Iron Eyes paddles downstream, it is transformed into an industrial and mechanical world of black oil, soot, coal, and garbage. Iron Eyes makes his way to shore with his canoe. After he pulls his canoe from the water, he has a bag of garbage thrown at his feet from a car on an interstate. A stern-voiced narrator then intones, “Some people have a natural abiding respect for the beauty of that was once this country, and some people don’t. People start pollution, and people can stop it.” Iron Eyes turns to the camera with a tear in his eye. The PSA ends as a symbol for Keep America Beautiful fills the screen the PSA is one of the best examples of how environmental groups can appeal to broader audiences with emotion (pathos), authority (ethos), and reasoning (logos).

Using Emotions to Draw a Contrast Between the Ideal and Real

This PSA’s appeals to emotion are its strongest arguments. AS the commercial starts, we can see Iron Eyes Cody in what we could consider to be his native land. He sits proud and tall as he paddles downstream. We can see his eyes and his face, and he looks as though he has heard some troubling news. The shot pans out and we see his silhouette against a gold-splashed river, pristine as can be. Then, the beauty of this natural scene comes to a crashing halt as a crumpled newspaper page floats by the canoe. The music shifts from a native-sounding melody to a mechanical booming sound. The silhouette of Iron Eyes and his canoe – the only reminder we have of what nature is intended to look like – is then shadowed as we reach an apex of filth: garbage-ridden water, smoggy air, oil, and massive steel barge. This scene dwarfs his canoe, and the music begins to sound desperate as it reaches its peak. Iron Eyes is turned transparent, a ghost of what respect humankind had for the earth, and he is juxtaposed against what is now: smokestacks and pollution. Quietly overwhelmed, Iron Eyes pulls his canoe ashore where still more waste permeates the surroundings. The trash thrown at Iron Eyes’ feet feels like a final insult that punctuates the scene.

We now know who is responsible for this tragedy: it is us. Our sense of emotional shame is triggered by the contrasts we have just seen the floating newspaper, the smog, sludge, smoke, muck, oil, grease, fumes, and garbage. Pollution is everywhere, and we now know that we are the cause. It is our fault – humanity’s fault. The appeal to pathos then reaches its pinnacle as Iron Eyes sheds a tear for what we have done to this land. We see a great contrast between the environment as he knew it and the way it is now.

Using a Symbolic Figure to Create a Sense of Authority

Dressed in classic Native American clothing, Iron Eyes Cody is a symbol of our fading past that appeals to our sense of ethos. When most people think of Native Americans, they think of how they taught the original settlers to live off the land. They think about the respect that American natives had for the land and nature. When the narrator says, “Some people have a natural abiding respect for the beauty that was once this country, and some people don’t,” the contrast between Iron Eyes Cody and his polluted surroundings feels sharp. In this way, the symbolic ethos of Iron Eyes demonstrates that the ruination around him is our doing, not his. He takes us on a journey that slowly opens our eyes to what we are responsible for – ruining nature. One might even suggest that Iron Eyes may be analogous to the earth itself. As the pollution thickens, the image of Iron Eyes fades from a vibrantly dressed Native American to a silhouette until he becomes a ghost of the past. Iron Eyes does nothing to change the pollution, nor does he attempt to change it. Instead, he observes it and feels it with pain, remorse, and despair. That’s the only thing that he and the earth can do.

Using Reasoning to Drive Home the Point

Finally, the PSA uses loges to drive home its point: “Some people have a deep and abiding respect for the natural beauty that was once this country. And some people don’t. People start pollution. People can stop it.” After this logical statement, we are given a five0second display of the Keep America Beautiful symbol, suggesting an answer. In the Web version, a Web site address is given where people can access information on how they can do something about pollution. The logic is inescapable: If you really care about the environment, stop doing more damage and start getting active in cleaning up the mess. The viewer’s next logical question is almost inescapably, “How can I do something?”

The Keep America Beautiful PSA has been a model for reaching out to the public about environmental issues. Its use of emotion, authority, and reasoning brings us face-to-face with our transgressions against nature. This PSA woke many people up and urged them to change their ways. Of course, the pollution problem has not been solved, but we seem to have turned the corner. Iron Eyes Cody is watching to see if we succeed.

Rhetorical Analysis Example #5: “Why Secret’s Super Bowl Ad With Carli Lloyd Shouldn’t Be Celebrated” by Hemal Jhaveri (USA Today 2 February 2020)

Secret has been co-opting the idea of women’s empowerment to sell deodorant since 1956. That kind of empty messaging is nothing new, but their Super Bowl ad, on which they spent millions. is the most glaring and expensive example of a brand trying to leverage gender equality in the most empty, meaningless way possible. In an email, Secret said the one-minute ad did not cost the reported going rate of $10 million as the commercial aired before the Super Bowl began.

The ad, which premiered on social media a few days before the Super Bowl, has an innocuous enough premise, but its laughable execution makes it borderline offensive to women and football fans.

The spot opens during a pivotal moment in football game, as a stadium full of tense fans watch as the team’s kicker comes onto the field. In suspenseful slow motion, the ball gets kicked. People stare with open mouths as it sails through the air and finally through the goalpost. There is wild cheering, from everyone, until the shocking, sudden reveal. The kicker and holder take off their helmets to reveal that they are actually U.S. Women’s National Team soccer players Carli Lloyd and Crystal Dunn! What a shock! The crowd gasps! There is sudden, stunned silences. Women! Playing football!

Just look at these stunned faces.

After the shock dissipates, the crowd cheers again, recovering from their sexist assumptions that women can’t be as good as men at sports.

It’s a baffling, dumb, stupidly executed ad that doesn’t actually understand the landscape of women’s sports or the challenges women athletes face, and also doesn’t care to address them. The problem isn’t just that fans would be unaccepting of female athletes in traditionally male dominated sports until they reveal themselves to be capable, but all the structural challenges keeping women athletes in secondary roles.

According to a release from Secret, the ad aims to spotlight “fierce female athletes” and is about “defying conventional expectations and championing equal opportunities for women.”

Yet, Lloyd and Dunn are phenomenal athletes in their own right. Why not just highlight their incredible accomplishments rather than try to recontextualize their worth through the male dominated lens of football?

There’s a reason Secret chose Llloyd for the spot, considering she went viral last year for kicking a 55-yard field goal during an Eagles practice session. It was an incredible feat, and lead to speculation that Lloyd could potentially become the first female NFL player. It would be incredible if that happened, but it shouldn’t take that leap for women athletes to be valued.

Secret’s poorly executed ad just reframes the misconception that, to prove themselves worthy, women have to succeed in male spaces. That is not the definition of equality. Women deserve to succeed on their own merits and their own abilities and in their own spaces. That’s what Lloyd and Dunn have already done.

Secret’s bizarre tagline for the campaign doesn’t help either. They’ve used the hashtag #KickInequality, but what does that even mean? Kick it where? To the curb? Out the door? Off the field? No idea. Down the road so another generation can deal with it?

In their press release for the ad, the deodorant company had plenty of platitudes about women’s empowerment and gender equality, but what they didn’t mention was any financial support for women’s athletes. Right now, women’s leagues are struggling for attention and funding. Just imagine how far that money they spent on Super Bowl ad time could go.

Rhetorical Analysis Example #6: “#CuttheCarls Because Women are #MoreThanMeat” (MLA Style)

Careful study of the symbolic artifacts of discourse (words, phrases, images, gestures, performances, texts, films) and the methods of persuasion that people use to communicate.

(385-323 BCE) a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato and mentor to Alexander the Great, he was the founder of the Lyceum, the Peripatetic school of philosophy, and the Aristotelian tradition.

The broad idea or issue that a message deals with.

The unique viewpoint, new information, or interesting take on a topic.

The circumstances that form the setting for an event, statement, or idea, and in terms of which it can be fully understood and assessed.

The groups of people (demographics) who receive a message.

The goal or objective that the creator of a message is trying to achieve by communicating that message.

the specific problem, incident, or situation that caused a writer to create their message.

the propitious moment for decision or action.

The group of people that an author is trying to reach with their message.

The group of people who actually receive a message.

A method of grouping people into categories for the purpose of collecting data.

A rhetorical appeal to logic, reason, and common sense.

A rhetorical appeal to authority, credibility, and character.

A rhetorical appeal to emotion.

(1927-2006) An American psychologist well-known for proposing a psychoevolutionary classification approach for general emotional responses.

Sources that require an Internet connection and/or electronic device (computer, DVD player, radio, television, etc.) to access. For example: websites, podcasts, videos, movies, television shows, audio recordings.

Sources that were originally intended to be accessed and read in physical, printed form. For example: books, newspapers, magazines, journals, newsletters, other periodicals or publications.

Source material that was collected by the researcher and analyzed for research purposes. For example: Personal experiences, field observations, interviews, surveys, case studies, experiments.

A beginning section which states the purpose and goals of the following writing, generally followed by the body and conclusion. The introduction typically describes the scope of the document and gives the brief explanation or summary of the document.

The main idea, point, or claim of a written work. Plural: theses.

The last paragraph in an academic essay that generally summarizes the essay, presents the main idea of the essay, or gives an overall solution to a problem or argument given in the essay.

Special words or expressions that are used by a particular profession or group and are difficult for others to understand.