11

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify and share attitudes about writing. (GEO 2,3; SLO 1)

- Demonstrate the stages of the writing process. (GEO 2; SLO 1)

- Communicate perceived writing strengths and weaknesses as well as writing goals for the course. (GEO 2, 3; SLO 1)

Defining the Term “Writing”

On the surface, nothing could be simpler than writing: You sit down, you pick up a pen or open a document on your computer, and you write words. But anyone who has procrastinated or struggled with writer’s block knows that the writing process is more arduous, if not somewhat mysterious and unpredictable.

People often think of writing in terms of its end product—the email, the report, the memo, essay, or research paper, all of which result from the time and effort spent in the act of writing. In this course, however, you will be introduced to writing as the recursive process of planning, drafting, and revising.

Writing is Recursive

You will focus as much on the process of writing as you will on its end product (the writing you normally submit for feedback or a grade). Recursive means circling back; more often than not, the writing process will have you running in circles. You might be in the middle of your draft when you realize you need to do more brainstorming, so you return to the planning stage. Even when you have finished a draft, you may find changes you want to make to an introduction. In truth, every writer must develop his or her own process for getting the writing done, but there are some basic strategies and techniques you can adapt to make your work a little easier, more fulfilling and effective.

Developing Your Writing Process

The final product of a piece of writing is undeniably important, but the emphasis of this course is on developing a writing process that works for you. Some of you may already know what strategies and techniques assist you in your writing. You may already be familiar with prewriting techniques, such as freewriting, clustering, and listing. You may already have a regular writing practice. But the rest of you may need to discover what works through trial and error. Developing individual strategies and techniques that promote painless and compelling writing can take some time. So, be patient.

A Writer’s Process: Ali Hale

Read and examine Ali Hale’s writing process (below). Think of this as a framework for defining the process in distinct stages: prewriting, writing, revising, editing, and publishing. You may already be familiar with these terms. You may recall from past experiences that some resources refer to prewriting as planning and some texts refer to writing as drafting.

Whether you know it or not, there’s a process to writing – which many writers follow naturally. If you’re just getting started as a writer, though, or if you always find it a struggle to produce an essay, short story or blog, following the writing process will help.

I’m going to explain what each stage of the writing process involves, and I’ll offer some tips for each section that will help out if you’re still feeling stuck!

1. Prewriting

Have you ever sat staring at a blank piece of paper or a blank document on your computer screen? You might have skipped the vital first stage of the writing process: prewriting. This covers everything you do before starting your rough draft. As a minimum, prewriting means coming up with an idea!

Ideas and Inspiration

Ideas are all around you. If you want to write but you don’t have any ideas, try:

-

- Using a writing prompt to get you started.

- Writing about incidents from your daily life, or childhood.

- Keeping a notebook of ideas – jotting down those thoughts that occur throughout the day.

- Creating a vivid character, and then writing about him/her.

See also How to Generate Hundreds of Writing Ideas.

Once you have an idea, you need to expand on it. Don’t make the mistake of jumping straight into your writing – you’ll end up with a badly structured piece.

Building on Your Idea

These are a couple of popular methods you can use to add flesh to the bones of your idea:

-

- Free writing: Open a new document or start a new page and write everything that comes into your head about your chosen topic. Don’t stop to edit, even if you make mistakes.

- Brainstorming: Write the idea or topic in the center of your page. Jot down ideas that arise from it – sub-topics or directions you could take with the article.

Once you’ve done one or both of these, you need to select what’s going into your first draft.

Planning and Structure

Some pieces of writing will require more planning than others. Typically, longer pieces and academic papers need a lot of thought at this stage.

First, decide which ideas you’ll use. During your free writing and brainstorming, you’ll have come up with lots of thoughts. Some belong in this piece of writing: others can be kept for another time.

Then, decide how to order those ideas. Try to have a logical progression. Sometimes, your topic will make this easy: in this article, for instance, it made sense to take each step of the writing process in order. For a short story, try the eight-point story arc.

2. Writing

Sit down with your plan beside you, and start your first draft (also known as the rough draft or rough copy). At this stage, don’t think about word-count, grammar, spelling, and punctuation. Don’t worry if you’ve gone off-topic, or if some sections of your plan don’t fit too well. Just keep writing!

If you’re a new writer, you might be surprised that professional authors go through multiple drafts before they’re happy with their work. This is a normal part of the writing process – no-one gets it right the first time.

Some things that many writers find helpful when working on the first draft include:

-

- Setting aside at least thirty minutes to concentrate: it’s hard to establish a writing flow if you’re just snatching a few minutes here and there.

- Going somewhere without interruptions: a library or coffee shop can work well, if you don’t have anywhere quiet to write at home.

- Switching off distracting programs: if you write your first draft onto a computer, you might find that turning off your Internet connection does wonders for your concentration levels! When I’m writing fiction, I like to use the free program Dark Room (you can find more about it on our collection of writing software).

- You might write several drafts, especially if you’re working on fiction. Your subsequent drafts will probably merge elements of the writing stage and the revising stage.

TIP: Writing requires concentration and energy. If you’re a new writer, don’t try to write for hours without stopping. Instead, give yourself a time limit (like thirty minutes) to really focus – without checking your email!

3. Revising

Revising your work is about making “big picture” changes. You might remove whole sections, rewrite entire paragraphs, and add in information which you’ve realized the reader will need. Everyone needs to revise – even talented writers.

The revision stage is sometimes summed up with the A.R.R.R. (Adding, Rearranging, Removing, Replacing) approach:

Adding

What else does the reader need to know? If you haven’t met the required word-count, what areas could you expand on? This is a good point to go back to your prewriting notes – look for ideas that you didn’t use.

Rearranging

Even when you’ve planned your piece, sections may need rearranging. Perhaps as you wrote your essay, you found that the argument would flow better if you reordered your paragraphs.

Removing

Sometimes, one of your ideas doesn’t work out. Perhaps you’ve gone over the word count, and you need to take out a few paragraphs. Maybe that funny story doesn’t really fit with the rest of your article.

Replacing

Would more vivid details help bring your piece to life? Do you need to look for stronger examples and quotations to support your argument? If a particular paragraph isn’t working, try rewriting it.

4. Editing

The editing stage is distinct from revision and needs to be done after revising. Editing involves the close-up view of individual sentences and words. It needs to be done after you’ve made revisions on a big scale: or else you could agonize over a perfect sentence, only to end up cutting that whole paragraph from your piece.

When editing, go through your piece line by line, and make sure that each sentence, phrase, and word is as strong as possible. Some things to check for are:

-

- Have you used the same word too many times in one sentence or paragraph? Use a thesaurus to find alternatives.

- Are any of your sentences hard to understand? Rewrite them to make your thoughts clear.

- Which words could you cut to make a sentence stronger? Words like “just” “quite”, “very”, “really” and “generally” can often be removed.

- Are your sentences grammatically correct? Look carefully for problems like subject-verb agreement and staying consistent in your use of the past, present or future tense.

- Is everything spelled correctly? Don’t trust your spell-checker – it won’t pick up every mistake. Proofread as many times as necessary.

- Have you used punctuation marks correctly? Commas often cause difficulties. You might want to check out the Daily Writing Tips articles on punctuation.

5. Publishing

The final step of the writing process is publishing. This means different things depending on the piece you’re working on.

Bloggers need to upload, format, and post their piece of completed work.

Students need to produce a final copy of their work, in the correct format. This often means adding a bibliography, ensuring that citations are correct, and adding details such as your student reference number.

Journalists need to submit their piece (usually called “copy”) to an editor. Again, there will be a certain format for this.

Fiction writers may be sending their story to a magazine or competition. Check guidelines carefully, and make sure you follow them. If you’ve written a novel, look for an agent who represents your genre. (There are books like Writer’s Market, published each year, which can help you with this.)

Conclusion

The five stages of the writing process are a framework for writing well and easily. You might want to bookmark this post so that you can come back to it each time you start on a new article, blog post, essay, or story: use it as a checklist to help you.

What is important to grasp early on is that the act of writing is more than sitting down and writing something. Please avoid the “one and done” attitude, something instructors see all too often in undergraduate writing courses. Use Hale’s essay as your starting point for defining your own process.

A Writer’s Process: Anne Lamott

In the video below, Anne Lamott, a writer of both nonfiction and fiction works, as well as the instructional novel on writing Bird by Bird: Instructions on Writing, discusses her own journey as a writer, including the obstacles she has to overcome every time she sits down to begin her creative process. She will refer to terms such as “the down draft,” “the up draft,” and “the dental draft.”

As you watch, think about how her terms “down draft,” “up draft,” “dental draft” work with those presented by Hale’s writing process. What does Lamott mean by these terms? Can you identify with her process or with the one Hale describes? How are they related?

Also, when viewing the interview, pay careful attention to the following timeframe: 11:23 to 27:27 minutes and make a list of tips and strategies you find particularly helpful. Think about how your own writing process fits with what Hale and Lamott have to say. Is yours similar? Different? Is there any new information you have learned that you did not know before exposure to these works?

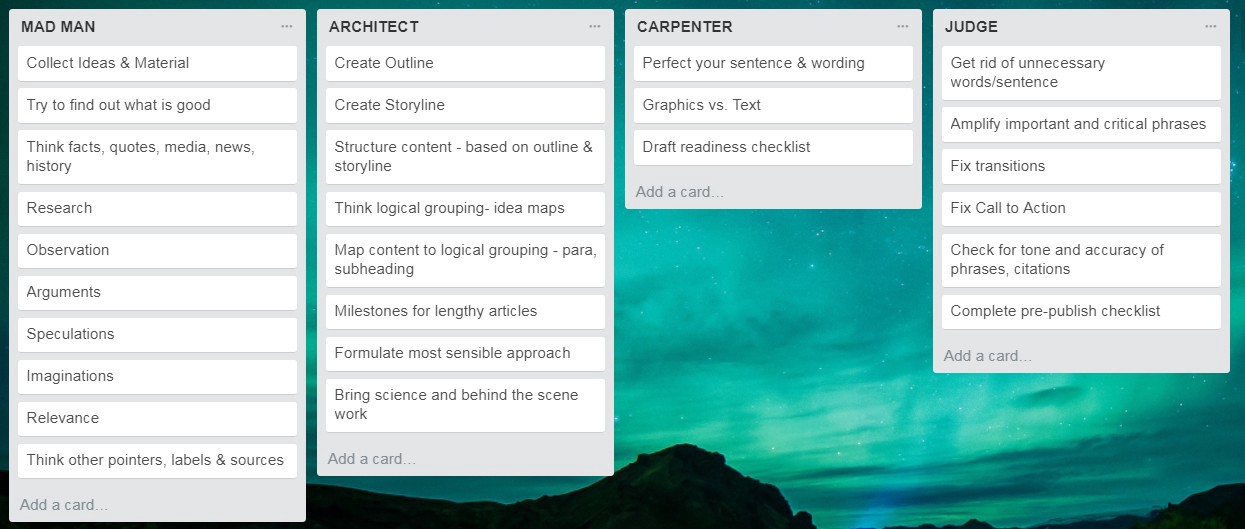

A Writer’s Process: Madman, Architect, Carpenter, Judge

Dr. Betty S. Flowers hypothesized that the writing process should be treated as a progression of roles. She submitted her ideas in a now-famous essay to the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) in 1981. At the time, Dr. Flowers was the associate dean of graduate studies and a professor of English at the University of Texas in Austin, and she eventually became the director of the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library at UT. She believed that writers should think of the different steps in the writing process as four distinct roles, and we should endeavor to fulfill each of those roles as we work through the process.

“What’s the hardest part of writing?” I ask on the first day of class.

“Getting started,” someone offers, groaning.

“No, it’s not getting started,” a voice in the back of the room corrects. “It’s keeping on once you do get started. I can always write a sentence or two-but then I get stuck.”

“Why?” I ask.

“I don’t know. I am writing along, and all of a sudden I realize how awful it is, and I tear it up. Then I start over again, and after two sentences, the same thing happens.”

“Let me suggest something which might help,” I say. Turning to the board, I write four words: “madman,” “architect,” “carpenter,” “judge.”

Then I explain: “What happens when you get stuck is that two competing energies are locked horn to horn, pushing against each other. One is the energy of what I’ll call your ‘madman.’ He is full of ideas, writes crazily and perhaps rather sloppily, gets carried away by enthusiasm or anger, and if really let loose, could turn out ten pages an hour.

“The second is a kind of critical energy-what I’ll call the ‘judge.’ He’s been educated and knows a sentence fragment when he sees one. He peers over your shoulder and says, ‘That’s trash!’ with such authority that the madman loses his crazy confidence and shrivels up. You know the judge is right-after all, he speaks with the voice of your most imperious English teacher. But for all his sharpness of eye, he can’t create anything.

“So you’re stuck. Every time your madman starts to write, your judge pounces on him.

“Of course this is to over-dramatize the writing process-but not entirely. Writing is so complex, involves so many skills of heart, mind and eye, that sitting down to a fresh sheet of paper can sometime seem like ‘the hardest work among those not impossible,’ as Yeats put it.

Whatever joy there is in the writing process can come only when the energies are flowing freely – when you’re not stuck.

“And the trick to not getting stuck involves separating the energies. If you let the judge with his intimidating carping come too close to the madman and his playful, creative energies, the ideas which form the basis for your writing will never have a chance to surface. But you can’t simply throw out the judge. The subjective personal outpourings of your madman must be balanced by the objective, impersonal vision of the educated critic within you. Writing is not just self-expression; it is communication as well.

“So start by promising your judge that you’ll get around to asking his opinion, but not now. And then let the madman energy flow. Find what interests you in the topic, the question or emotion that it raises in you, and respond as you might to a friend – or an enemy. Talk on paper, page after page, and don’t stop to judge or correct sentences. Then, after a set amount of time, perhaps, stop and gather the paper up and wait a day.

“The next morning, ask your ‘architect’ to enter. She will read the wild scribblings saved from the night before and pick out maybe a tenth of the jottings as relevant or interesting. (You can see immediately that the architect is not sentimental about what the madman wrote; she is not going to save every crumb for posterity.) Her job is simply to select large chunks of material and to arrange them in a pattern that might form an argument. The thinking here is large, organizational, paragraph level thinking-the architect doesn’t worry about sentence structure.

“No, the sentence structure is left for the ‘carpenter’ who enters after the essay has been hewn into large chunks of related ideas. The carpenter nails these ideas together in a logical sequence, making sure each sentence is clearly written, contributes to the argument of the paragraph, and leads logically and gracefully to the next sentence. When the carpenter finishes, the essay should be smooth and watertight.

“And then the judge comes around to inspect. Punctuation, spelling, grammar, tone-all the details which result in a polished essay become important only in this last stage. These details are not the concern of the madman who’s come up with them, or the architect who’s organized them, or the carpenter who’s nailed the ideas together, sentence by sentence. Save details for the judge.”

When you find yourself stuck when writing a paper, think of yourself first as the madman. Don’t get held down by details and schematics. Think of the important things first, what you have an emotional reaction to. You can engage the judge, architect, and carpenter later to make your work coherent and polished.

What is an Essay?

If you were asked to describe an essay in one word, what would that one word be?

Okay, well, in one word, an essay is an idea.

No idea = no essay.

But more than that, the best essays have original and insightful ideas.

Okay, so the first thing we need to begin an essay is an insightful idea that we wish to share with the reader.

But original and insightful ideas do not just pop up every day. Where does one find original and insightful ideas?

Let’s start here: an idea is an insight gained from either a) our personal experiences, or b) in scholarship, from synthesizing the ideas of others to create a new idea.

In this class, we start with a personal essay in which your own personal experiences are a source for your ideas.

Life teaches us lessons. We learn from our life experiences. This is how we grow as human beings. Before you start on your essays, reflect on your life experiences by employing one or more of the brainstorming strategies described in this course. Your brainstorming and prewriting assignments are important assignments because remember: no idea = no essay. Brainstorming can help you discover an idea for your essay. So, ask yourself: What lessons have I learned? What insights have I gained that I can write about and share with my reader? Your reader can learn from you.

Why do we write?

We write to improve our world; it’s that simple. We write personal essays to address the most problematic and fundamental question of all: What does it mean to be a human being? By sharing the insights and lessons we have learned from our life experiences, we can add to our community’s collective wisdom.

We write to improve our world; it’s that simple. We write personal essays to address the most problematic and fundamental question of all: What does it mean to be a human being? By sharing the insights and lessons we have learned from our life experiences, we can add to our community’s collective wisdom.

We respect the writings of experts. And, guess what? You are an expert! You are the best expert of all on one subject—your own life experiences. When we write personal essays, we research our own life experiences and describe those experiences with rich and compelling language to convince our reader that our idea is valid.

In this class, your own life experiences will be the springboard for the development of academic writing skills.

Often students say to me: “I am so young; I do not have any meaningful insights into life.” Well, you may not be able to solve the pressing issues of the day, but think of it this way. What if a younger brother or sister came to you and in an anxious voice said; “I’ve got to do X. I’ve never had to do X. You’ve had some experience with X. Can you give me some advice?” You may have some wisdom and insights from your own life experience with X to share with that person. Don’t worry about solving the BIG issues in this class. You can serve the world as well by simply addressing, and bringing to life in words, the problems and life situations that you know best, no matter how mundane. Please notice that with rare exception the essays you will read in this class do not cite outside sources. They are all written from the author’s actual life experiences. Think of your audience as someone who can learn from your life experiences and write to them and for them.

The recursive process of planning, drafting, and revising.

Circling back.

1. A thought or suggestion as to a possible course of action.

2. The aim or purpose.

A short work of autobiographical nonfiction characterized by a sense of intimacy and a conversational manner.