8

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Cite sources to give credit to other authors and researchers. (GEO 2; SLO 2)

- Quote other authors and speakers. (GEO 2; SLO 2)

- Use paraphrase and summary to explain the ideas of others. (GEO 2; SLO 2)

- Frame quotes, paraphrases, and summaries in your texts. (GEO 2; SLO 2)

- Avoid plagiarizing the words and ideas of others. (GEO 4; SLO 2)

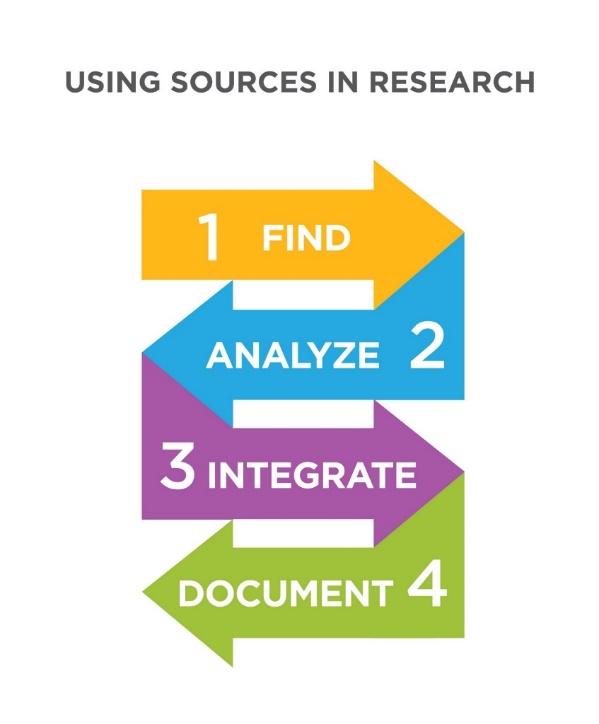

When researching a topic in college or in the workplace, you need to do more than collect sources. You also need to take the next step and engage with your sources, using them to develop your ideas and support your claims. Research allows you to extend the work of others and to advance your ideas clearly, persuasively, and with authority. Your writing will have more authority when you use sources to inform and support your ideas. Also, by engaging with the ideas of others, you enter a larger conversation about those ideas within a particular discipline or profession. In this chapter, you will learn four methods for incorporating sources into your writing:

When researching a topic in college or in the workplace, you need to do more than collect sources. You also need to take the next step and engage with your sources, using them to develop your ideas and support your claims. Research allows you to extend the work of others and to advance your ideas clearly, persuasively, and with authority. Your writing will have more authority when you use sources to inform and support your ideas. Also, by engaging with the ideas of others, you enter a larger conversation about those ideas within a particular discipline or profession. In this chapter, you will learn four methods for incorporating sources into your writing:

- Citing sources gives credit to other authors and researchers while demonstrating that you have done your research properly. Citations also allow your readers to locate your sources for their own purposes.

- Quoting sources allows you to use keywords, phrases, or passages taken directly from the works of others. A direct quote conveys the original text’s immediacy and authority while capturing its tone and style.

- Paraphrasing sources helps you explain a source’s specific ideas or describe its major points using your own words and sentence structures. Typically, a paraphrase will be about the same length as the material in the source.

- Summarizing sources allows you to condense a source down to just its major ideas and points. Summaries often describe what authors say and also how they say it. They can also describe an author’s underlying values, reasoning processes, or evidence.

This chapter will show you how to incorporate the ideas and words of others into your work while giving appropriate credit. Section V of this textbook will show you how to quote and cite your sources using MLA Style. To start, watch the following video, which provides a look at the methods of quoting and citing sources:

Quoting

When quoting an author or speaker, you are importing their exact words into your document. To signal that these words are not yours, always place quotation marks around them and include a parenthetical citation. Quoting sounds pretty easy, but you can confuse your readers or even get yourself in trouble if you don’t properly copy and cite the works of others. You might even be accused of plagiarism. Here are some helpful guidelines.

Short Quotations

A brief quotation takes a word, phrase, or sentence directly from an original source. Always introduce and provide some background about the quotation: Do not expect a quotation to make your point by itself.

Words

If an author uses a word in a unique way, you can put quotes around it in your own text. After you tell your reader where the word comes from, you don’t need to continue putting it inside quotation marks.

Examples

Acceptable quotation: Using Gladwell’s terms, some important differences exist between “explicit” learning and “collateral” learning (36).

Unacceptable quotation: Using Gladwell’s terms, some important differences exist between explicit learning and collateral learning (36).

Phrases

If you want to use a whole phrase from a source, you need to put quotation marks around it. Then weave the quote into a sentence, making sure it flows with the rest of your writing.

Examples

Acceptable quotation: Tomorrow’s educators need to understand the distinction between, as Gladwell puts it, “two very different kinds of learning” (36).

Unacceptable quotation: Tomorrow’s educators need to understand the distinction between, as Gladwell puts it, two very different kinds of learning (36).

Sentences

You can also bring entire sentences from another source into your document. Use a signal phrase (see the end of this chapter for a full list) or a colon to indicate that you are quoting a whole sentence.

Examples

Acceptable quotation: As Gladwell argues, “Meta-analysis of hundreds of studies done on the effects of homework shows that the evidence supporting the practice is, at best, modest” (36).

Unacceptable quotation: As Gladwell argues, meta-analysis of hundreds of studies done on the effects of homework shows that the evidence supporting the practice is, at best, modest.

Acceptable quotation using a colon: Gladwell summarizes the research this way: “Meta-analysis of hundreds of studies done on the effects of homework shows that the evidence supporting the practice is, at best, modest” (36).

Unacceptable quotation using a colon: Gladwell summarizes the research this way: Meta-analysis of hundreds of studies done on the effects of homework shows that the evidence supporting the practice is, at best, modest.

Long Quotations

Occasionally, you may need to quote a source at length. A quote longer than three lines should be formatted as a blockquote. A blockquote indents the entire quotation to separate it from your normal text. No quotation marks are used, and the citation appears at the end of the quote, outside the final punctuation.

Example

A child is unlikely to acquire collateral learning through books or studying for the SAT exams, Gladwell explains. They do acquire it through play:

The point is that books and video games represent two very different kinds of learning. When you read a biology textbook, the content of what you read is what matters. Reading is a form of explicit learning. When you play a video game, the value is in how it makes you think. Video games are an example of collateral learning, which is no less important. (“Brain” 2)

In asserting that collateral learning “is no less important” than explicit learning, Gladwell implies that American education may be producing students who are imbalanced—with too much content knowledge and too little facility in dealing with unstructured situations, the kinds of situations that a person is likely to face every day of his or her working life. (2)

Use blockquotes only when the original quotation cannot be paraphrased and must be preserved in its full length. Don’t expect a long quotation to make your point for you. Instead, use the quote to support the point you are making.

Paraphrasing and Summarizing

When paraphrasing or summarizing, you are putting someone else’s ideas into your own words. In some situations, using a paraphrase or summary is preferable to using a quote. Using too many quotations can make a text look choppy and might lead the reader to think that you are just stitching together passages from other people’s works. Paraphrasing allows you to maintain the tone and flow of your writing. There are four main differences between a paraphrase and a summary:

- A paraphrase handles only a portion of the original text, while a summary often covers its entire content.

- A paraphrase usually follows the organization of the original source, while a summary reorganizes the content to highlight the major points.

- A paraphrase is usually about the same length or a little shorter than the original text being paraphrased, while a summary is significantly shorter than the original text.

- A paraphrase looks through the text to convey what the author is saying, but summaries can also look at the text to explore an author’s strategies, style, reasoning, and other choices (see Chapter 6: Critical Reading, Analytical Thinking).

The excerpt below will be used to demonstrate paraphrasing and summarizing.

“Brain Candy”

From the book Outliers by Malcolm Gladwell

The point is that books and video games represent two very different kinds of learning. When you read a biology textbook, the content of what you read is what matters. Reading is a form of explicit learning. When you play a video game, the value is in how it makes you think. Video games are an example of collateral learning, which is no less important.

Being “smart” involves facility in both kinds of thinking—the kind of fluid problem solving that matters in things like video games and I.Q. tests, but also the kind of crystallized knowledge that comes from explicit learning. If Johnson’s book has a flaw, it is that he sometimes speaks of our culture being “smarter” when he’s really referring just to that fluid problem-solving facility. When it comes to the other kind of intelligence, it is not clear at all what kind of progress we are making, as anyone who has read, say, the Gettysburg Address alongside any Presidential speech from the past twenty years can attest. The real question is what the right balance of these two forms of intelligence might look like. Everything Bad Is Good for You doesn’t answer that question. But Johnson does something nearly as important, which is to remind us that we shouldn’t fall into the trap of thinking that explicit learning is the only kind of learning that matters.

One of the ongoing debates in the educational community, similarly, is over the value of homework. Meta-analysis of hundreds of studies done on the effects of homework shows that the evidence supporting the practice is, at best, modest. Homework seems to be most useful in high school and for subjects like math. At the elementary-school level, homework seems to be of marginal or no academic value. Its effect on discipline and personal responsibility is unproved. And the causal relation between high-school homework and achievement is unclear: it hasn’t been firmly established whether spending more time on homework in high school makes you a better student or whether better students, finding homework more pleasurable, spend more time doing it. So why, as a society, are we so enamored of homework? Perhaps because we have so little faith in the value of the things that children would otherwise be doing with their time. They could go out for a walk, and get some exercise; they could spend time with their peers, and reap the rewards of friendship. Or, Johnson suggests, they could be playing a video game, and giving their minds a rigorous workout.

Paraphrasing

The goal of paraphrasing is to explain and describe a portion of the source’s text in your own words. A paraphrase is usually about the same length or a little shorter than the material being paraphrased. The following acceptable and unacceptable paraphrases explain Gladwell’s distinction between “explicit” and “collateral” learning.

Acceptable Paraphrase

In this acceptable paraphrase, the writer used primarily her own words. When she used exact words from Gladwell’s article, she placed them inside quotations. Now let’s look at a paraphrase that is too close to the original source:

Unacceptable Paraphrase

The underlining in this unacceptable paraphrase indicates places where the writer has lifted words and phrases directly from Gladwell’s article. Even though the writer cites the source, she should have placed these exact words and phrases inside quotation marks.

When paraphrasing, make sure it’s your voice, and not the source’s voice, that comes through. Notice how the voice in the unacceptable paraphrase is overwhelmed by the voice of the source. However, in the acceptable paraphrase, the writer’s voice comes through clearly.

Summarizing

When summarizing a source, you are capturing its principal idea or ideas in a condensed form. A summary often also explores and describes the author’s choices, including the source’s structure; its tone, angle, or thesis; its style; its underlying values; or its persuasive strategies. In the following summaries, the writers address the main idea in Gladwell’s review: the right balance between “explicit” and “collateral” learning.

Acceptable Summary

Notice how this summary focuses on Gladwell’s main point and makes it prominent. An unacceptable summary usually relies too much on the wording of the original text, and it may not prioritize the most important points in the source text.

Unacceptable Summary

The underlined phrases in this unacceptable summary show where the writer uses almost the same wording or structure as the original text. This is called “patchwriting,” which writing scholar Rebecca Moore Howard defines as “copying from a source text and then deleting some words, altering grammatical structures, or plugging in one synonym for another” (xvii). Patchwriting is a form of plagiarism and is discussed later in this chapter.

When to Quote vs. When to Paraphrase

The real “art” to research writing is using quotes and paraphrases from evidence effectively in order to support your point. There are certain “rules,” dictated by the rules of style you are following, such as the ones presented by the MLA. There are certain “guidelines” and suggestions, like the ones offered in the previous section and the ones you will learn from your teacher.

But when all is said and done, the question of when to quote and when to paraphrase depends a great deal on the specific context of the writing and the effect you are trying to achieve. Learning the best times to quote and paraphrase takes practice and experience.

In general, it is best to use a quote when:

- The exact words of your source are important for the point you are trying to make. This is especially true if you are quoting technical language, terms, or very specific word choices.

- You want to highlight your agreement with the author’s words. If you agree with the point the author of the evidence makes and you like their exact words, use them as a quote.

- You want to highlight your disagreement with the author’s words. In other words, you may sometimes want to use a direct quote to indicate exactly what it is you disagree about. This might be particularly true when you are considering the antithetical positions in your research writing projects.

In general, it is best to paraphrase when:

- There is no good reason to use a quote to refer to your evidence. If the author’s exact words are not especially important to the point you are trying to make, you are usually better off paraphrasing the evidence.

- You are trying to explain a particular piece of evidence in order to explain or interpret it in more detail. This might be particularly true in writing projects like critiques.

- You need to balance a direct quote in your writing. You need to be careful about directly quoting your research too much because it can sometimes make for awkward and difficult to read prose. So, one of the reasons to use a paraphrase instead of a quote is to create balance within your writing.

Citing

Whenever you integrate the ideas, findings, or arguments of others into your own writing, you need to give them credit by citing them with a parenthetical reference. This in-text citation should correspond to a full bibliographical citation in your paper’s Works Cited page. In most situations, a parenthetical reference will include an author’s name and the number of the page on which the information appears. In some situations, the year of the source is also included.

Typically, a parenthetical reference will appear at the end of the sentence. In some situations, the citation should appear in the middle of a sentence if the ideas in the remainder of the sentence are not attributable to the source:

Examples

Economists have long questioned whether tax cuts, especially tax cuts for the wealthy, truly stimulate growth (Mitchell 93).

Economists have long questioned whether tax cuts, especially tax cuts for the wealthy, truly stimulate growth (Mitchell 93), but politicians are still making that old “trickle down” argument today.

If you use the author’s name within the sentence, the parenthetical citation at the end of the sentence should include only the page number.

Example

In MLA Style, if you have listed more than one source by an author in the Works Cited, indicate which source you are citing by including a shortened title before the page number.

Example

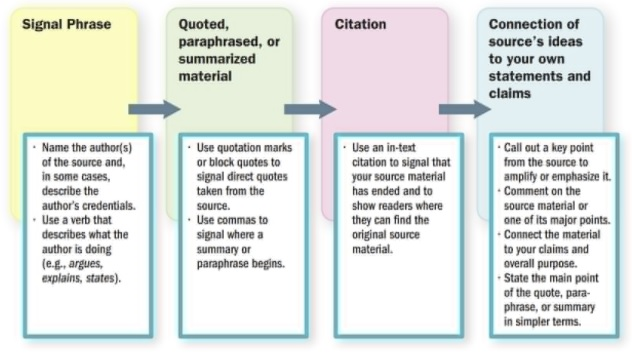

Framing Quotes, Paraphrases, and Summaries

Your readers need to see the boundaries between your work and the material you are taking from your sources. To help your readers identify these boundaries, you should frame your quotations, paraphrases, and summaries by using signal phrases, by citing sources, and by making connections to your own ideas.

- Signal phrase. A signal phrase indicates where the source material comes from. The words “as” and “in” are often at the heart of a signal phrase (e.g., “As Gladwell argues,” “In his article ‘Brain Candy,’ Gladwell states”).

- Source Information. Material quoted directly from your source should be separated from your own words with commas, quotation marks, and other punctuation to indicate which words came directly from the source and which are your own.

- Citation. An in-text citation directs readers to the original source’s location, identifying the exact pages or Web site. In MLA documentation style, a parenthetical reference is used to cite the source.

- Connection. When you connect the source’s ideas to your ideas, you will make it clear how the source material fits in with your own statements and claims.

Figure 22.1 color codes these features. The following example uses these colors to highlight signal phrases, source material, citations, and connections.

As Malcolm Gladwell reminds us, many American schools have eliminated recess in favor of more math and language studies, favoring “explicit” learning over “collateral” learning (“Brain” 36). This approach is problematic, because it takes away children’s opportunities to interact socially and problem-solve, which are critical skills in today’s world.

Speculating about why we so firmly believe that homework is critical to academic success, Gladwell suggests, “Perhaps because we have so little faith in the value of the things that children would otherwise be doing with their time” (36). In other words, Gladwell is arguing that we are so fearful of letting children play that we fill up their time with activities like homework that show little benefit.

Similarly, Steven Pink describes several studies that show that the careers of the future will rely heavily on creativity and spatial recognition, which means people who can think with the right side of their brain will have the advantage (65). If so, then we also need to change our educational system so that we can strengthen our abilities to think with both sides of the brain, not just the left side.

As shown in this example, the frame begins with a signal phrase. Signal phrases typically rely on an action verb that indicates what the author of the source is trying to achieve in the material that is being quoted, paraphrased, or summarized (see the chart at the end of this chapter). The frame typically ends with a connection showing how the source material fits into your overall discussion or argument. Your connection should do one of the following things for your readers:

- Call out a key point from the source to amplify or emphasize it.

- Expand on the source material or one of its major points

- Connect the source material to your claims and overall purpose.

- Rephrase the main point of the source material in simpler terms.

When handled properly, framing allows you to clearly signal the boundaries between your source’s ideas and your ideas. Use verbs like these (below)in your signal phrases to introduce quotations, paraphrases, and summaries.

| accepts | comments | explains | quarrels |

| accuses | compares | expresses | reacts |

| acknowledges | complains | finds | reasons |

| adds | concedes | grants | refutes |

| admits | concludes | holds | rejects |

| advises | confirms | illustrates | remarks |

| agrees | considers | implies | replies |

| alleges | contends | insists | reports |

| allows | countercharges | interprets | responds |

| analyzes | criticizes | maintains | reveals |

| announces | declares | notes | shows |

| answers | demonstrates | objects | states |

| argues | denies | observes | suggests |

| asks | describes | offers | supports |

| asserts | disagrees | points out | urges |

| believes | discusses | proclaims | writes |

| charges | disputes | proposes | |

| claims | emphasizes | provides |

Each of a set of punctuation marks, single (‘ ’) or double (“ ”), used to mark the beginning and end of a title or quoted passage.

A group of words taken from a text or speech and repeated by someone other than the original author or speaker, noted with quotation marks.

In MLA Style, a method of formatting long quotations of three lines or more.

Source information expressed in the writer/researcher's own words, usually to achieve greater clarity.

A brief statement or account of the main points of a source, written by the writer/researcher.

The rhetorical mixture of vocabulary, tone, point of view, and syntax that makes phrases, sentences, and paragraphs flow in a particular manner.

A citation style in which partial citations that reference a bibliographical citation are enclosed within parentheses and embedded in the text, either within or after a sentence.

The brief form of a source reference that included the text of an essay.

A reference to a source used in a scholarly work that contains the relevant information about that source's publication.

In MLA Style, the bibliography (list of sources used) is referred to as the Works Cited page.

The style recommended by the Modern Language Association (MLA) for preparing scholarly manuscripts and student research papers. It concerns itself with the mechanics of writing, such as punctuation, quotation, and, especially, documentation of sources.