22

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Work successfully with peers and work colleagues in groups. (GEO 3)

- Work successfully in teams by planning well and managing conflict. (GEO 3)

- Use peer response to offer and receive helpful feedback. (GEO 2, 3)

Throughout college and your career, the ability to work in teams will be an important asset. With a team, you can combine your ideas and personal strengths with the ideas and strengths of others. You can see new perspectives and take on larger and more complex projects. Plus, working in a team can be satisfying and fun. Collaborating with others is useful at every stage of the writing process. Early in the writing process, you and your team can brainstorm ideas, work on outlines, and research topics together. Later, you can help each other improve the organization, style, and design of your drafts. And during any stage of the writing process, you can use peer response to evaluate ideas or exchange suggestions for organizing and editing.

Computers and the Internet have made working in teams an efficient and essential part of writing. You probably already use social networking, e-mail, and texting to keep in touch with friends and family. In your college courses and your career, you will collaborate with colleagues and clients using file-sharing and real-time co-authoring tools. Your professors and supervisors will ask you to work collaboratively in three ways:

- Group Work: In college classes, you will be asked to discuss readings in groups, work on in-class group activities, and give feedback for revising your current projects. In the workplace, groups often meet to share information, brainstorm, and develop new products and services.

- Team Work: In college and the workplace, you will work with teams on larger projects, submitting one document or project for the whole team (Figure 15.1).

The ability to work with others is essential, whether you’re collaborating face to face or with Internet-based co-authoring tools. - Peer Response and Document Cycling: In small groups, you will need to revise, edit, and proofread the writing of others, offering advice and suggestions for improvement. In the workplace, peer response is called “document cycling” because important texts are routed through multiple people at the organization for revision, editing, and proofreading.

During your academic life so far, turning in assignments you completed by your-self probably feels normal. However, in your career, you will need to compose and revise collaboratively in teams. In surveys, employers rate the ability to “work well in teams” as one of the most important skills they are looking for in new employees. College is a good time to develop those collaboration skills.

Working Successfully in Groups

In college, you will be working in small groups regularly. Your professors will ask you and a group of other students to:

- Discuss readings

- Generate new ideas for projects

- Offer feedback on the ideas and work of others

- Work together on in-class tasks and assignments

Group meetings are also important in the workplace. Weekly and sometimes daily, work groups will meet in person or virtually to brainstorm new concepts, dis-cuss current progress, share concerns, and solve everyday problems.

In the workplace, your role will usually be defined by your position at the company. In college classes, your role may not be clear. So choosing roles up front helps members sort out who is doing what. When working in groups, each member should adopt one or two of these common roles:

- Facilitator. The facilitator keeps the group moving forward and on task. The facilitator also makes sure everyone has a chance to contribute. When the group wanders off task, the facilitator should remind the group members what they are trying to achieve and when they need to complete the task. If a member of the group has been quiet, the facilitator should make room for that person to contribute.

- Scribe. The scribe takes notes that team members can review periodically. This helps everyone remember what has been discussed and decided. The scribe may also check in with the group to ensure that the notes accurately and completely reflect the issues your group considered and the decisions you made.

- Spokesperson. The spokesperson is responsible for reporting on the group’s progress to the class or professor. While the group is discussing a reading or doing an activity, the spokesperson should take notes and think about what she or he is going to say to the class.

- Innovator. The innovator should feel free to shake things up by asking the group to consider the issue from other perspectives. The innovator should look for ways to be creative and different, even if he or she might suggest something that the rest of the group will resist or reject.

- Designated skeptic. The designated skeptic’s job is to help the group resist groupthink and push beyond simplistic responses to the issues under discussion. The skeptic should bring up concerns that a critic might use to raise doubts about what the group members have decided.

These roles can be combined. For instance, one person might serve as both facilitator and spokesperson, or scribe and designated skeptic. These roles should also be rotated throughout the semester so that everyone has a chance to be a facilitator, scribe, spokesperson, innovator, and skeptic.

Working Successfully in Teams

Teams work collaboratively on projects they will hand in together. Working with a team, you can take on larger, more complex projects, while blending your unique abilities with those of others.

But let’s just admit something upfront. Working in teams doesn’t always work out. Slackers sometimes don’t get their work done. Sometimes, members of your team waste time chatting about their weekend plans. One member keeps checking his phone. In some cases, you end up doing more than your share of the work, and that can be frustrating.

There are slackers out there, even in the workplace, but most people want to do their best and want to do their share of the work. Groups break down when people don’t know what they are supposed to do, often because the group hasn’t made a plan. That’s why successful groups need to spend some time upfront planning out the project and defining each person’s role. Only then are they able to get down to work.

Planning the Project

During the planning phase, you and your team members should set goals, figure out the deadlines, and divide up the work. While planning, you should also talk about how you are going to resolve any disagreements that will arise during the project.

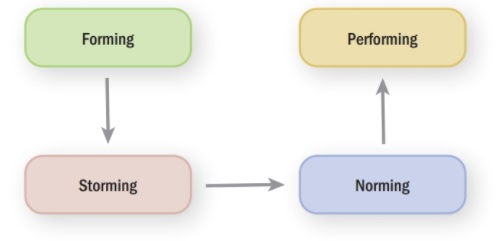

One helpful way to plan a team project is to use the “Four Stages of Teaming” developed by management guru Bruce Tuckman (Figure 15.2). Tuckman noticed that teams tend to go through four stages when working on a project:

- Forming. Getting to know each other, defining goals and outcomes, setting deadlines, and dividing up the work.

- Storming. Experiencing disagreements, sensing tension and anxiety, doubting the leadership, facing conflict, and feeling uncertain and frustrated.

- Norming. Developing consensus, revising the project’s goals, refining expectations of outcomes, solidifying team roles.

- Performing. Sharing a common vision, delegating tasks, feeling empowered, and resolving conflicts and differences in constructive ways.

The secret to working in teams is recognizing that these stages are foreseeable and almost predictable—including the storming stage. Good planning helps teams work through these stages effectively.

Forming: Setting Goals, Getting Organized

When a new team is formed, the members should first get to know each other and discuss the expectations of the project.

Hold a planning meeting.

At a planning meeting, do some or all of the following:

- Ask all team members to introduce themselves.

- Define the purpose of the project and its goals.

- Describe the expected outcomes of the project.

- Identify the strengths and interests of each team member.

- Divide up the work.

- Create a project calendar and set deadlines.

- Agree on how conflicts will be solved when they arise (because they will).

Choose team responsibilities.

Each member of the team should take on a clearly defined role. When working on a project, your group might consider assigning these four roles:

- Coordinator. This person is responsible for maintaining the project schedule and running the meetings. The coordinator is not the “boss.” Rather, she or he is responsible for keeping people in touch and maintaining the project schedule.

- Researchers. One or two group members should be assigned to collect information. They are responsible for digging up material at the library, running searches on the Internet, and coordinating any empirical research.

- Editor. The editor is responsible for the organization and style of the document. He or she identifies missing content and places where the document needs to be reorganized. The editor is also responsible for creating a consistent voice, or style, in the document.

- Designer. The designer sketches out how the document will look, gathers images from the Internet, creates graphs and charts, and takes photographs.

Notice that there is no “writer” in this list. Everyone on your team should be responsible for writing a section or two of the document. Everyone should also be responsible for reading and responding to the sections written by others.

Storming: Managing Conflict

Conflicts will happen. They are a normal part of any team project, so you need to learn how to manage any conflicts that come up. In fact, professors divide classes into teams because they want you to learn how to manage conflict in constructive ways. Here are some strategies and tips for managing conflict:

Run efficient meetings.

Before each meeting, the coordinator should list what will happen, what will be achieved, and when the meeting will end. In the workplace, this list of meeting topics is called an “agenda.” At the end of a meeting, each team member should state what she or he will do on the project before the next meeting. Write those commitments down and hold people to them.

Encourage participation from everyone.

During the meeting, each team member should have an opportunity to contribute ideas and opinions. No one should be allowed to sit back and leave the decisions to others. If a team member is not participating, the coordinator should ask that person to offer his or her opinion.

Allow dissent (even encourage it).

Everyone should feel welcome to dis-agree or offer alternative ideas for consideration. In fact, dissent should be encouraged, because it often leads to new and better ways of completing the project. If team members are agreeing on everything too easily, you might ask, “What would a critic or skeptic say about our project?” “How might someone else do this project?”

Mediate conflicts.

People will become irritated and even angry with each other. When conflicts surface, give each side time to think through and state their position. Then identify the two to five issues that the sides disagree about. Rank these issues from most important to least. Address each of these issues separately, and try to negotiate a solution to the conflict.

Motivate the slackers.

Slackers can kill the momentum of a team and undermine its ability to finish the project. If someone is slacking, your team should make your expectations clear to that person as soon as possible. Often, slackers simply need a straightforward list of tasks to complete, along with clear deadlines. If a slacker still refuses to participate, you might ask the professor to intervene or even to remove that person from the team.

Always remember that conflict is normal and inevitable in teams. When you see conflict developing in your team, remind yourself that the team is just going through the storming stage of the teaming process (that’s a good thing). While in college, you should practice managing these kinds of uncomfortable situations so you can better handle them in your career.

Norming: Getting Down to Work

Soon after the storming stage, your team will enter the norming stage. Norming gives your group an opportunity to refine the goals of the project and complete the majority of the work.

Revise project goals and expected outcomes.

At a meeting or in a Web conference, your team should look back at the original goals and outcomes you listed during the planning stage. Sharpen your goals and clarify what your team will accomplish by the end of the project.

Adjust team responsibilities.

Your team should redistribute the work so the burden is shared fairly among team members. Doing so will raise the morale of the group and allow the work to get finished by the deadline. Also, if everyone feels the workload is fairly divided, your team will usually avoid slipping back into the storming stage.

Revise the project calendar.

Unexpected challenges and setbacks have probably already put your team a little behind schedule, so spend some time working out some new deadlines. These dates will need to be firmer than the ones you set in the forming stage because you are getting closer to the final deadline.

Use online collaborative tools.

You can’t always meet face to face, so you should agree to work together online. Online collaborative sites such as Google Docs allow team members to view the document’s editing history, revert to previous versions of a document, and even work on the same document simultaneously. A voice connection is helpful when you are working on a document together.

Keep in touch with each other.

Depending on the project deadline, your group should be in touch with each other daily. Texting, emailing, and social networking work well for staying connected. If you aren’t hearing regularly from someone, call, text, or e-mail that person. Regular contact will help keep the project moving forward.

Performing: Working as a Team

Performing usually occurs when teams are together for a long time, so it’s rare that a team in a one-semester class will reach the performing stage. During this stage, each team member recognizes the others’ talents, abilities, and weaknesses. While performing, your team is doing more than just trying to finish the project. At this point, every-one on the team is looking for ways to improve how the work is getting done, leading to higher-quality results (and more satisfaction among team members). This is as much as we are going to say about performing. Teams usually need to be together for several months or even years before they reach this stage. If your team in a college class reaches the performing stage, that’s fantastic. If not, that’s fine, too. The performing stage is a goal you should work toward in your advanced classes and in your career, but it’s not typical in a college writing course.

Using Peer Response to Improve Your Writing

Peer response is one of the most common forms of collaboration in college. By sharing drafts of your work with others, you can receive useful feedback while also helping yourself and others succeed on the assignment. Because peer review involves probing and commenting on the writing choices that others have made in their drafts, it is similar to the reflecting you do in your own writing. In this way, critiquing others’ drafts helps you improve your writing skills and your reflecting skills.

Types of Peer Response and Document Cycling

Peer response can be used at any stage during the writing process but it usually happens after a good draft has been completed. The most common peer response strategies include:

- Rubric-centered editing. The professor provides the rubric that he or she will be using to evaluate the paper. In groups of three to five members, responders use the rubric to highlight places where their peers’ drafts can be improved. In some cases, your professor might ask you to score each other’s papers according to the rubric.

- Analysis with a Worksheet. The professor provides a worksheet that uses targeted questions to draw the responders’ attention to key features of the paper. The worksheet will often ask responders to highlight and critique specific parts of the paper, such as the thesis sentence and topic sentences in paragraphs.

- Read-aloud. In a group of three to four people, the draft’s author stays silent as another person reads the draft out loud. The others in the group listen and take notes about what they hear. Then the members of the group discuss the draft’s strengths—while the author stays silent—and make suggestions for improvement. Afterward, the author can respond to the group’s comments and ask follow-up questions.

- Round Robin. A draft of the paper is left on a desk or on a computer screen. Then, readers rotate every 15–20 minutes to a new desk or workstation, offering written suggestions for improving each paper. At the end of the class, each paper will have received comments from three or more different readers. Hint: In a computer classroom, the “Review” or “Suggesting” function of a word processor is a great way to add comments in the margins of papers.

- Document Cycling. Each paper is shared through a common storage site like Google Drive, Dropbox, or OneDrive. Alternatively, it can be sent to two or three other people via e-mail. Each person is then responsible for offering critiques of two or three papers from other members of the group.

Keep in mind that peer response isn’t just about helping others improve their papers. By paying attention to what works and doesn’t work in the writing of others, you will improve your own skills.

Using Digital Tools for Peer Review

Exchanging printouts of drafts is a messy and confusing process that requires multiple face-to-face meetings among peers. The process has become far more efficient with a variety of digital tools that make collaboration easier, such as file-sharing services Dropbox, Google Drive, Box, and OneDrive. Alternatively, digital tools allow multiple users to access, edit, and save files in the Cloud. Some of these services (Google Docs, Sheets, Slides, and OneDrive/SharePoint) are also real-time co-authoring tools, which allow you and others to work on the same document at the same, whether you’re sitting next to each other or are in different countries. These tools are very common in today’s workplace, so now is a good time to start using them.

Some of these Internet-based tools are available and free for anyone to use. Others, like those in some course-management systems, are specifically designed for doing peer review.

Responding Helpfully During Peer Response

While offering a peer response, you are engaging with both the paper and the author. Here are five guidelines to follow when responding to someone else’s draft:

- Guideline One: Read the entire paper before responding. First, you should gain a sense of the whole paper before offering comments to the author. That way, you can respond to the most important issues rather than reacting sentence by sentence. With a full read, you gain a sense of the author’s purpose, audience, and angle. This big-picture understanding of the context will allow you to offer meaningful comments about the author’s writing choices.

- Guideline Two: Read like a reader. Read the paper again. This time, you should “read like a reader,” responding to each paragraph as a normal reader would. When the writer has intentionally written for a specific group of readers, try to assume the role of such readers and respond as you think they would respond. Readers tend to evaluate the strength of ideas, not hunt for spelling errors and grammar problems.

- Guideline Three: Identify strengths as well as weaknesses. Always try to balance criticism with praise and advice. Of course, it’s your job to help other writers identify what is not working in their papers and what is unclear. Keep in mind, though, that it’s just as important to highlight what works well.

- Guideline Four: Explain the reasons behind your reading. Always provide the reasons that support both your praise and blame. If you are making a suggestion for improvement, start by explaining why something doesn’t work—why you feel that the author should consider different writing choices in light of the intended purpose, readers, and context. Offer strategies for making specific improvements. For instance, you might make suggestions like this: “Because your readers are going to be reading this on computer and smartphone screens, I think you should consider breaking up long paragraphs like this into smaller chunks.”

- Guideline Five: Use genre and writing-specific terminology. In this class and this book, you are learning a set of terms about genres and writing that you and your classmates share. Use those terms to frame your responses. That way, you and the others will use a common vocabulary to offer ideas for improving drafts.

Students and even work colleagues sometimes hesitate to offer honest critiques of others’ writing. They are concerned about hurting another person’s feelings or giving bad advice. In truth, your classmates and colleagues want your honest and specific feedback so they can improve their writing skills and succeed with a project.

If you are uncomfortable or unsure about giving advice, try this trick: Say, “This is good, and here’s how I would make it better.” In other words, start out by reassuring the author that the paper is interesting and valued. Then, offer some ideas about how you would improve it. Framing your comments in terms of “improvement” will give both you and the author more confidence.