4

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Develop your own dependable “research process” that will help you inquire into topics that interest you. (GEO 2, 4; SLO 1,2)

- Devise a “research plan” for your project that allows you to stay on schedule and keep track of sources and evidence. (GEO 2, 4; SLO 1, 2)

Research allows you to systematically explore topics by collecting factual evidence, consulting secondary sources, and using your hands-on experiences. Research allows you to do three important things:

- Inquire: You can gather evidence to investigate an issue and explain it to other people.

- Acquire knowledge: You can collect and analyze facts to increase or strengthen your knowledge about a subject. In some cases, research can allow you to add knowledge to what is already known.

- Support an argument: You can use research to persuade others and support a particular side of an argument while gaining a full understanding of the opposing view.

Doing research requires more than simply finding books or articles that agree with your preexisting opinion. You also need to look beyond the first page of hits from an Internet search engine like Google. Instead, research is about pursuing the truth and developing knowledge, whether the facts agree with your opinion or not. In this chapter, you will learn how to develop your own research process. A depend-able research process allows you to write and speak with authority, because you will be more confident about the evidence you collect and the reliability of the sources you choose to use. Following a consistent research process will save you time while helping you find useful and trustworthy sources of evidence.

Starting the Research Process

The research process is very similar to the scientific method. Both have the same goal: to come to a verifiable conclusion through careful study and research.

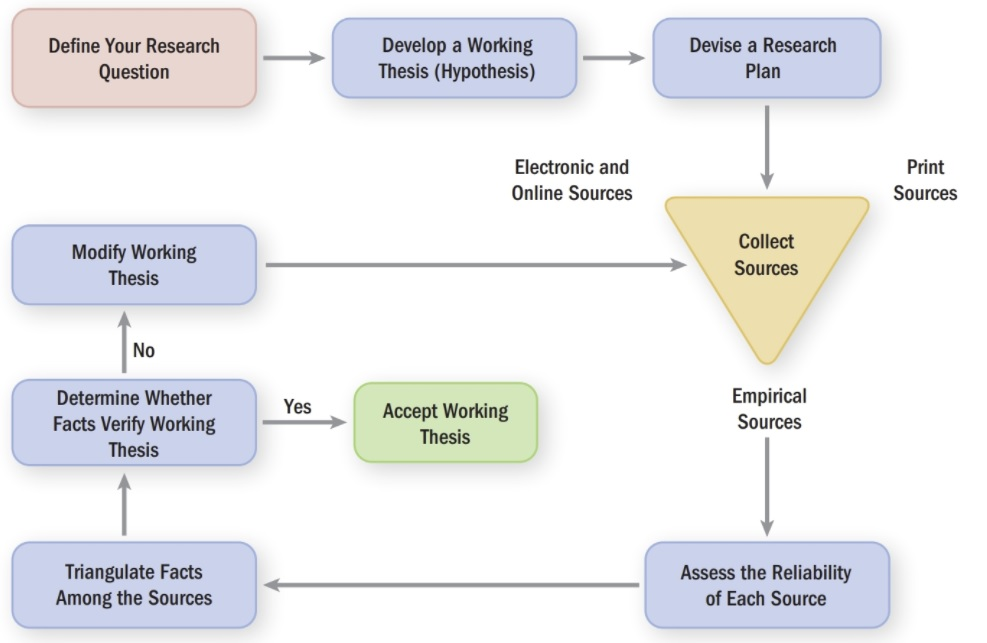

A reliable research process, as shown in Figure 18.1, is recursive, which means the researcher collects evidence and then repeatedly tests it against a working thesis. This cyclical process ends when the working thesis fits the evidence you collected.

1. Define the Five Elements of the Rhetorical Situation

- Topic: What am I being asked to write about?

- Angle: What is new or has changed recently about this topic?

- Context: Where and when will they be reading this document?

- Audience: Who will read this document, and what do they expect?

- Purpose: What exactly is the assignment asking me to accomplish?

The previous chapter (Chapter 17: Elements of the Rhetorical Situation) discusses these elements in depth.

2. Determine the Research Question

Your research question identifies what you want to discover about your topic. Name your topic and then write down a question your research will try to answer:

Examples

Topic: The anti-vaccine movement in the United States.

Research Question: Why are some people, including celebrities, choosing not to vaccinate their kids against common illnesses like measles, mumps, and whooping cough?

Topic: The oddity of wearing shorts and flip-flops in wintertime.

Research Question: Why do some college students wear shorts and flip-flops in the middle of the winter?

Once you have drafted a research question, spend some time narrowing it to a topic that you can answer in a college-length paper. The research questions mentioned above, for example, are too broad for a typical college paper. Here are more focused versions of those questions:

Examples

Is the anti-vaccine movement a real national threat, or is it primarily a problem for people who live in places like California with dense populations and many unvaccinated people?

Why do some students at Falls County Community College wear shorts and flip-flops to class, even in the middle of the winter?

3. Draft a Working Thesis

After defining your research question, you should then develop a working thesis, which is sometimes called a hypothesis in other fields. Your working thesis is your best guess at this moment about the answer to your research question.

Try to boil your thesis statement down to one sentence. For example, here are some working theses based on the research questions above:

Examples

Even here in northern Michigan, vaccinations are still critical for all children because illnesses spread quickly over the winter since we spend more time indoors in confined spaces.

Several Falls County Community College students wear shorts and flip-flops in the winter because they prefer light, comfortable clothing, and they can keep warm by staying inside and walking from building to building across campus, but others do it because they think it’s fashionable and cool.

Try to boil your working thesis down to one sentence. If you require two or three sentences to state your working thesis, your topic may be too complex or too broad. As you do your research, it is likely that your working thesis will change. Eventually, the final version of your working thesis will become the main claim for your project.

4. Find Sources

A source is a collection of information that can be used in an essay. Pay attention to the types of sources you use, such as what medium they are from, what their origins are, and who their audience is. You want to make sure that all your sources meet the assignment requirements, which might mean that you are only looking at recent or peer-reviewed sources. Chapter 19: Types of Sources discusses the different types of sources in more depth.

One way to manage your sources is to develop a research plan. Your plan should describe the kinds of evidence, including evidence from outside sources, you will need to answer your research question. Your plan should also describe how you are going to collect this evidence, along with your deadlines for finding sources. You will learn more about finding sources in the next chapter.

5. Collect Material From Sources

Look for quotes from experts, real-life examples, facts, and statistics. Differentiate between quotes (the original source’s exact words) and paraphrases (the source information put into your own words) by putting quotation marks around quotes, but not around paraphrases Information should be “bite-sized” – you will only be using small pieces of information, not whole paragraphs at a time, in your essays. One way of collecting source material is the old-fashioned note card method. If it can’t fit on the front of a notecard, it’s probably too long.

6. Group the Source Information

Look through the information you’ve collected, such as on the notecards. Group information on similar topics. These individual topics will become your body paragraphs. Chapter 12: Body Paragraphs provides more information on developing the body of your essay.

7. Organize the Essay

Now that you know what your different paragraphs will be about, you can decide what order they should go in. Then, you can organize your note cards so that you know what order you’ll be presenting your information in your essay. If you collected any useful or interesting pieces of information that didn’t fit into the topics of your body paragraphs, consider using them in your introduction or conclusion. Now, you have an exact outline of how your research will be presented in your essay. Chapter 9: Essay Organization further explains how to organize and outline your essay.

8. Revise the Working Thesis

The working thesis, like a hypothesis, should point you to an endpoint and give you an idea of when your research is complete. Now that you know what will actually be included in your essay, and in what order, you can revise your thesis to fit your outline.

A thesis should accomplish three things:

- Identify your topic to your reader (if you have not already done so).

- Clearly state the main point you are trying to prove.

- Summarize the evidence you’ll be using to support your point.

Remember to list your evidence in the same order you’ll be presenting it in your essay. Chapter 11: Thesis Statements further explains what is expected of your thesis.

9. Write the Rough Draft

Follow the outline from step #7. Try writing your essay in order (introduction, body paragraphs, conclusion) as the final product will have a more consistent voice and cohesive flow to it. Insert your source information into the draft as you write it – it’s not a good idea to simply put placeholders or leave yourself notes, because there’s no guarantee you’ll remember exactly what you wanted when you put them there (See Chapter 22: Source Integration). Remember to differentiate between quotations and paraphrases or summaries as you insert source information, because you should always put quotation marks around quotes and you should never do so with paraphrases or summaries. (See Chapter 34: Quotations and Chapter 35: Paraphrases and Summaries). It’s also a good idea to include the source reference when you insert source information. In MLA Style, we use parenthetical references as the in-text citations (see Chapter 33: In-Text Citations). It’s always better to have too much information or too much writing in a rough draft, because it’s easier to delete information than go back several steps to add more in.

10. Finalize the Draft

Go through the four stages of editing: global revision, substantive editing, copyediting, and proofreading. The editing process is discussed in Chapter 14: Editing and Revision.

Managing Your Research Process

When you finish your start-up research, you should have enough information to finalize a schedule for completing your research. At this point, you should also start a bibliographic file to help keep track of your sources.

Finalizing a Research Schedule

You might find “backward planning” helpful when finalizing your research schedule. Backward planning means working backward from the deadline to today, filling in all the tasks that need to be accomplished. Here’s how to do it:

1. On your screen or a piece of paper, list all the tasks you need to complete.

2. On your calendar, mark a final deadline for finishing your research. Then, fill in your deadlines for drafting, designing, and revising your project.

3. Work backward from your research deadline, filling in the tasks you need to accomplish and identifying the days on which each task needs to be completed. Online calendars like those from Google, Microsoft Outlook, Mozilla, or Yahoo! are great tools for creating research schedules. A low-tech paper calendar still works well, too.

Starting Your Bibliography File

One of the first tasks on your research schedule should be to set up a file on your computer that holds a working bibliography of the sources you find. Each time you find a useful source, add it to your bibliography file. As you collect each source, record all the information for a full bibliographic citation (you will learn how to cite sources in Chapter 32: Bibliographical Citations).

Following and Modifying Your Research Plan

You should expect to modify your research plan as you move forward with the project. In some cases, you will find yourself diverted from your research plan by interesting facts, ideas, and events that you didn’t know about when you started. That’s fine. Let the facts guide your research, even if they take you in unexpected directions. Also, check in regularly with your research question and working thesis to make sure you are not drifting too far away from your original idea for the project. In some cases, you might need to adjust your research question and working thesis to fit some of the sources or new issues you have discovered.

When Things Don’t Go as Expected

Research is a process of inquiry—of exploring, testing, and discovering. You are going to encounter ideas and issues that will require you to modify your approach, research question, or working thesis. Expect the unexpected, make any necessary changes, and then move forward.

Roadblocks to research. You may not be able to get access to all the sources you had planned on using. For example, you might find that the expert you wanted to interview is unavailable, or that the book you needed is checked out or missing from the library, or that you simply cannot find the data or evidence you expected to use. Don’t give up. Instead, modify your approach and move around the roadblock.

Evidence and ideas that change your working thesis. You might find something unexpected that alters or completely changes how you view your topic. For instance, the evidence you collect might not support your working thesis after all. Or you might find that a different, more focused working thesis is more interesting to you or more relevant for your audience. Rather than getting distracted or disappointed, consider this an opportunity to discover something new. Modify your research question or working thesis and move forward.

These temporary roadblocks can be frustrating, but following unexpected paths can also make research fun. They can lead you to new breakthroughs and exciting innovations.

The systematic investigation into and study of materials and sources in order to establish facts and reach new conclusions.

A collection of information that supplies material for research purposes.

A method of procedure that has characterized natural science since the 17th century, consisting in systematic observation, measurement, and experiment, and the formulation, testing, and modification of hypotheses.

Circling back.

Any set of circumstances that involves at least one person (the author) communicating a message to at least one other person (the audience).

The broad idea or issue that a message deals with.

The unique viewpoint, new information, or interesting take on a topic.

The circumstances that form the setting for an event, statement, or idea, and in terms of which it can be fully understood and assessed.

The goal or objective that the creator of a message is trying to achieve by communicating that message.

A question that a research project sets out to answer.

A break or pause within poetry or prose.

A supposition or proposed explanation made on the basis of limited evidence as a starting point for further investigation.

The main idea, point, or claim of a written work. Plural: theses.

A group of words taken from a text or speech and repeated by someone other than the original author or speaker, noted with quotation marks.

A piece of informatin that is known or proven to be true.

Source information expressed in the writer/researcher's own words, usually to achieve greater clarity.

The majority of an essay in which claims are presented and subsequently proven, described, analyzed, or explained.

A self-contained unit of discourse in writing dealing with a particular point or idea.

A general plan or overview giving the essential features of an essay but not the detail.

A beginning section which states the purpose and goals of the following writing, generally followed by the body and conclusion. The introduction typically describes the scope of the document and gives the brief explanation or summary of the document.

The last paragraph in an academic essay that generally summarizes the essay, presents the main idea of the essay, or gives an overall solution to a problem or argument given in the essay.

The rhetorical mixture of vocabulary, tone, point of view, and syntax that makes phrases, sentences, and paragraphs flow in a particular manner.

The grammatical and lexical linking within a text or sentence that holds a text together and gives it meaning (also called "flow").

Related to "cohesive"

A brief statement or account of the main points of a source, written by the writer/researcher.

Each of a set of punctuation marks, single (‘ ’) or double (“ ”), used to mark the beginning and end of a title or quoted passage.

A citation style in which partial citations that reference a bibliographical citation are enclosed within parentheses and embedded in the text, either within or after a sentence.

The brief form of a source reference that included the text of an essay.

A completed but unpolished version of an essay.

The first stage of global editing in which the writer reexamines and reconsiders their project’s topic, angle, and purpose, and their understanding of their readers and the context.

A form of local editing that revises a document for the purposes of clarity, cohesion, and consistency.

The final stage of the editing process that inspects surface features and writing mechanics, such as grammar, syntax, punctuation, diction, and style.

A list of the sources referred to in a scholarly work, typically printed as an appendix.

A reference to a source used in a scholarly work that contains the relevant information about that source's publication.