5

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Recognize the differences between primary, secondary, and tertiary sources. (GEO 1; SLO 2)

- Triangulate your research by collecting evidence from electronic, print, and empirical resources. (GEO 2; SLO 2)

Now that you have figured out your working thesis and research plan, you are ready to start collecting sources. In this chapter, you will learn how to find a variety of primary and secondary sources that will help you research your topic and uncover useful evidence.

Using Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Sources

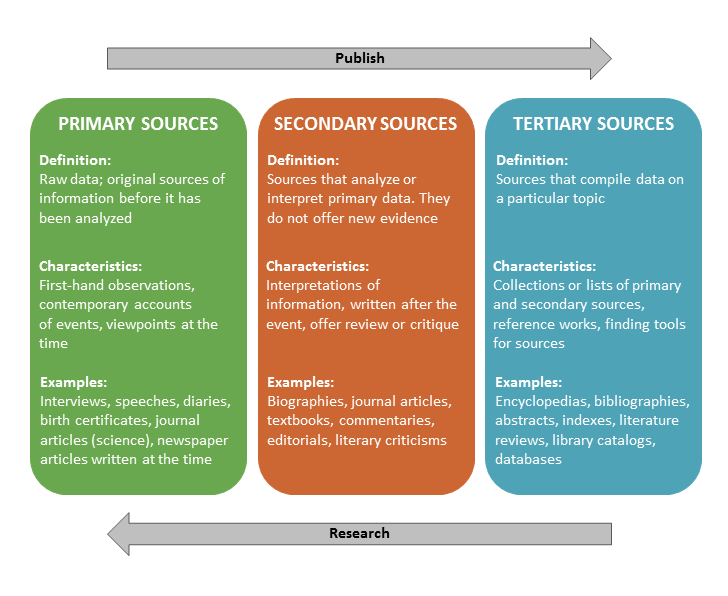

Professional researchers tend to distinguish between three types of sources: primary, secondary, and tertiary sources. All are important for doing reliable research.

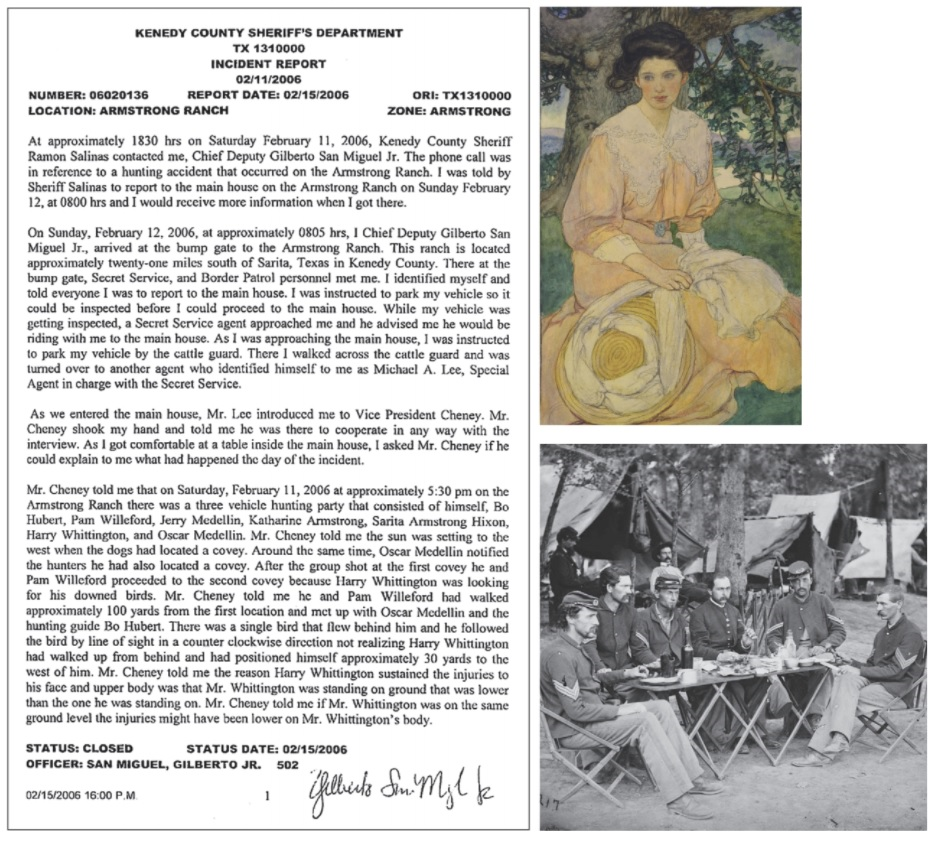

Primary Sources

Primary sources are the actual records or artifacts, such as letters, photographs, videos, memoirs, books, or personal papers, that were created by the people involved in the issues and events you are researching (Figure 19.1). These sources can also include any data, observations, or interview answers that you or others collected from empirical methods.

Secondary Sources

Secondary sources are the writings of scholars, experts, and other knowledgeable people who have studied your topic. Scholarly books and articles by historians are secondary sources because their authors analyze and reflect critically on past events. Secondary sources also include books, academic journals, magazines, newspapers, and blogs.

You will usually rely on secondary sources for most college papers. However, you should always look for opportunities to collect evidence from primary sources, such as archives, interviews, surveys, and observations. Collecting your own evidence allows you to confirm or challenge the information you find in secondary sources.

Tertiary Sources

Tertiary sources provide overviews of topics by synthesizing information gathered from other resources. These sources often provide data in a convenient form or provide information with context by which to interpret it.

The distinctions between primary, secondary, and tertiary sources can be ambiguous. An individual document may be a primary source in one context and a secondary source in another. Encyclopedias are typically considered tertiary sources, but a study of how encyclopedias have changed on the Internet would use them as primary sources. Time is a defining element.

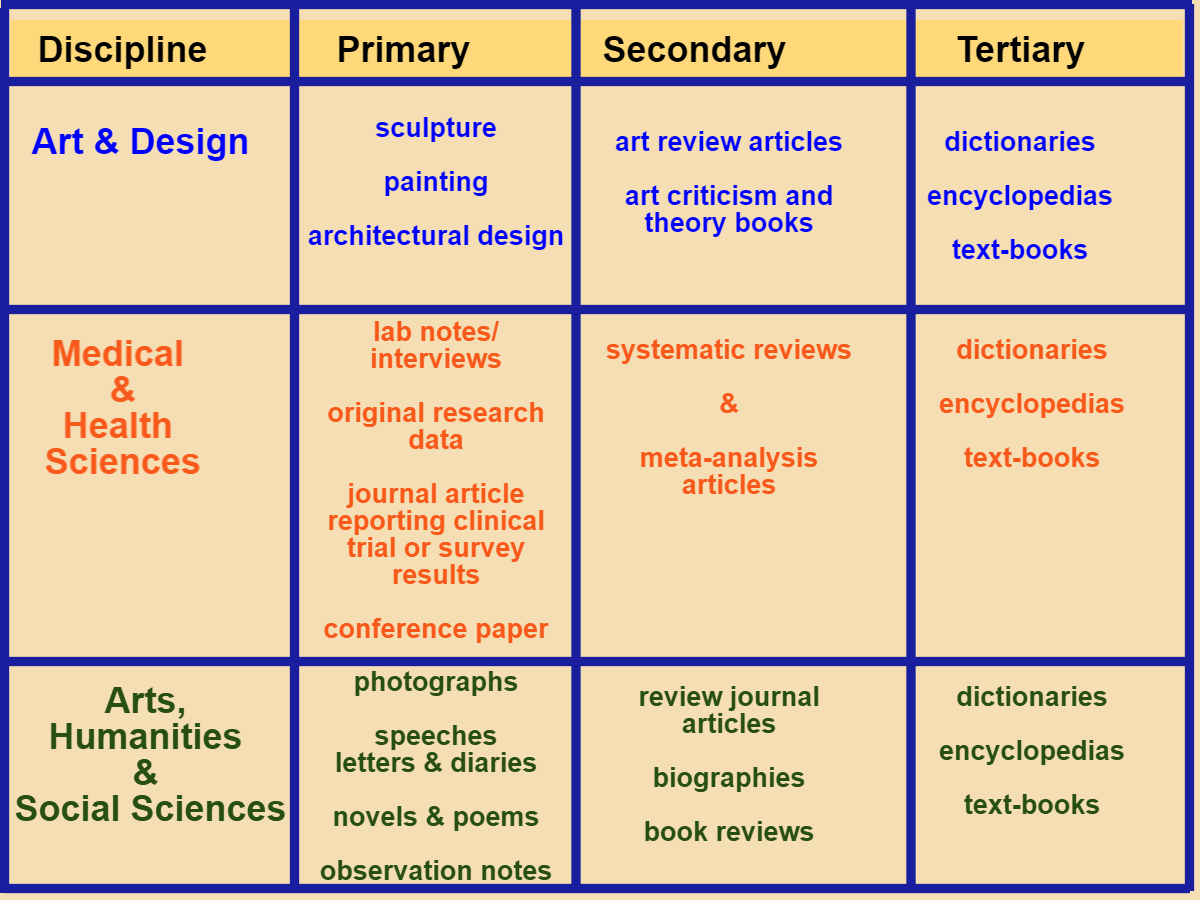

While these definitions are clear, the lines begin to blur in the different discipline areas, as demonstrated in the chart below:

Evaluating Sources with Triangulation

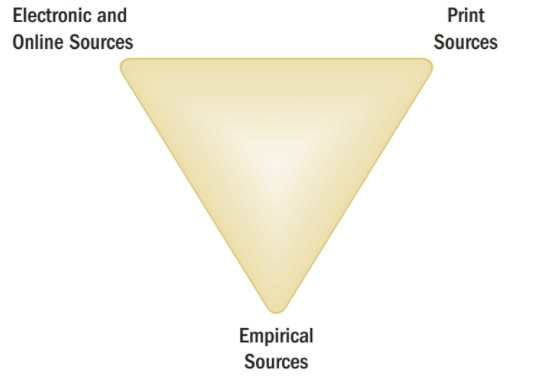

When doing any kind of research, try to collect evidence from a variety of sources and perspectives. If you rely on just one type of source, especially the Internet, you risk developing a limited or inaccurate understanding of your topic. To avoid this problem, you should triangulate your research by looking for evidence from three different types of sources:

- Electronic and online sources: Web sites, podcasts, videos, DVDs, listservs, television, radio, and blogs.

- Print sources: Books, journals, magazines, newspapers, government publications, reference materials, and microform/microfiche.

- Empirical sources: Personal experiences, archives, field observations, interviews, surveys, case studies, and experiments.

Together, these three types of sources are called the research triangle (Figure 18.2).

Here’s how the research triangle works:

- Probably reliable: If you collect similar evidence from all three kinds of sources, the evidence you found is probably reliable.

- Somewhat reliable: If you gather com-parable evidence from only two points of the triangle, your findings are prob-ably still reliable but are open to some doubt.

- Unreliable: If you can only find comparable evidence from one point on the triangle, then you should be skeptical. You probably need to do more research to back up your findings with other kinds of primary and secondary sources.

Of course, finding similar evidence in all three types of sources doesn’t make something true. It just means the evidence is probably trustworthy. Triangulation is a good way to evaluate your sources and corroborate the facts you uncover about your topic, but it won’t guarantee the truth of what you find. Also, remember that there are always at least two sides to any issue. So don’t just look for sources that support your working thesis. Even if you completely disagree with one of your sources, its argument and evidence might give you a stronger understanding of your own position.

| Electronic Sources | Print Sources | Empirical | |

| Pros: | Easy to access; immediate answers | Reliable; generally trustworthy | Specificity; ensures accuracy |

| Cons: | Unreliable; can be biased | Timeliness | Requires extra time, effort, skill |

“Popular” vs. “Scholarly” Sources

Research-based writing assignments in college will often require that you use scholarly sources in the essay. Different from the types of popular sources found in newspapers or magazines, scholarly sources have a few distinguishing characteristics.

|

|

Popular Source |

Scholarly Source |

|

Intended Audience |

Broad: readers are not expected to know much about the topic already |

Narrow: readers are expected to be familiar with the topic before-hand |

|

Author |

Journalist: may have a broad area of specialization (war correspondent, media critic) |

Subject Matter Expert: often has a degree in the subject and/or extensive experience on the topic |

|

Research |

Includes quotes from interviews. No bibliography. |

Includes summaries, paraphrases, and quotations from previous writing done on the subject. Footnotes and citations. Ends with bibliography. |

|

Publication Standards |

Article is reviewed by editor and proofreader |

Article has gone through a peer-review process, where experts on the field have given input before publication |

Where to Find Scholarly Sources

The first step in finding scholarly resources is to look in the right place. Sites like Google, Yahoo, and Wikipedia may be good for popular sources, but if you want something you can cite in a scholarly paper, you need to find it from a scholarly database. Your school library pays to subscribe to these databases, to make them available for you to use as a student.

Immediate, first-hand accounts of a topic, from people who had a direct connection with it.

One step removed from primary sources (though they often quote or otherwise use primary sources), secondary sources can cover the same topic, but add a layer of interpretation and analysis.

A source that indexes, abstracts, organizes, compiles, or digests other sources.

Sources that require an Internet connection and/or electronic device (computer, DVD player, radio, television, etc.) to access. For example: websites, podcasts, videos, movies, television shows, audio recordings.

Sources that were originally intended to be accessed and read in physical, printed form. For example: books, newspapers, magazines, journals, newsletters, other periodicals or publications.

Source material that was collected by the researcher and analyzed for research purposes. For example: Personal experiences, field observations, interviews, surveys, case studies, experiments.

A source written by experts in a particular field that serves to keep others interested in that field up to date on the most recent research, findings, and news (also called peer-reviewed or academic sources).

A source intended for a general audience of readers and written typically to entertain, inform, or persuade.