7

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Assess whether sources are reliable and trustworthy. (GEO 4; SLO 2)

Why Is Evaluating Research Important?

The Pacific Northwest Tree Octopus

A few years ago, a little-known animal species suddenly made headlines. The charming but elusive Tree Octopus became the focal point of internet scrutiny.

If you’ve never heard of the Pacific Northwest Tree Octopus, take a few minutes to learn more about it on this website, devoted to saving the endangered species. You can also watch this brief video for more about the creatures:

Source Reliability

If you’re starting to get the feeling that something’s not quite right here, you’re on the right track. The Tree Octopus website is a hoax, although a beautifully done one (Figure 21.1). There is no such creature, unfortunately.

Many of us feel that “digital natives”–people who have grown up using the internet–are naturally web-savvy. However, a 2011 U.S. Department of Education study that used the Tree Octopus website as a focal point revealed that students who encountered this website completely fell for it. According to an NBC news story by Scott Beaulieu, “In fact, not only did the students believe that the tree octopus was real, they actually refused to believe researchers when they told them the creature was fake.”

While this is a relatively harmless example of a joke website, it helps to demonstrate that anyone can say anything they want on the internet. A good-looking website can be very convincing, regardless of what it says. The more you research, the more you’ll see that sometimes the least-professional-looking websites offer the most credible information, and the most-professional-looking websites can be full of biased, misleading, or outright wrong information.

There are no hard and fast rules when it comes to resource reliability. Each new source has to be evaluated on its own merit, and this chapter will offer you a set of tools to help you do just that.

In this chapter, you’ll learn about tips and techniques to enable you to find, analyze, integrate, and document sources in your research.

Evaluating Source Material

When you search for information, you’re going to find lots of it . . . but is it good information? You will have to determine that for yourself, and the CRAAP Test can help. The CRAAP Test is a list of questions to help you evaluate the information you find. Different criteria will be more or less important depending on your situation or need. The CRAAP Test was developed by the Meriam Library of California State University, Chico. You have read and/or save a handout they developed for the CRAAP test here.

1. Currency: The timeliness of the information.

- When was the information published or posted?

- Has the information been revised or updated?

- Does your topic require current information, or will older sources work as well?

- Are the links functional?

Depending on your topic, sources can quickly become obsolete. In some fields, like cancer research, a source that is only a few years old might already be out of date. In other fields, like geology or history, data or facts that are decades old might still be relevant today. So pay attention to how rapidly the field is changing. You can consult your professor or a research librarian about whether a source should be considered up to date.

2. Relevance: The importance of the information for your needs.

- Does the information relate to your topic or answer your question?

- Who is the intended audience?

- Is the information at an appropriate level (i.e. not too elementary or advanced for your needs)?

- Have you looked at a variety of sources before determining this is the one you will use?

- Would you be comfortable citing this source in your research paper?

Your task as a researcher is to determine the appropriateness of the information your source contains, for your particular research project. It is a simple question, really: will this source help me answer the research questions that I am posing in my project? Will it help me learn as much as I can about my topic? Will it help me write an interesting, convincing essay for my readers?

3. Authority: The source of the information.

- Who is the author / publisher / source / sponsor?

- What are the author’s credentials or organizational affiliations?

- Is the author qualified to write on the topic?

- Is there contact information, such as a publisher or email address?

- Does the URL reveal anything about the author or source (examples: .com .edu .gov .org .net)?

To determine whether a source’s author and publisher are trustworthy, you should use an Internet search engine to check out their backgrounds and expertise. If you cannot find further information about the author or publisher—or if you find questionable credentials or reputations—you should look for other sources that are more credible.

4. Accuracy: The reliability, truthfulness, and correctness of the content.

- Where does the information come from?

- Is the information supported by evidence?

- Has the information been reviewed or refereed?

- Can you verify any of the information in another source or from personal knowledge?

- Does the language or tone seem unbiased and free of emotion?

- Are there spelling, grammar or typographical errors?

You should be able to confirm your source’s evidence by consulting other independent sources. If just one source offers a specific piece of evidence, you should treat it as unverified and use it cautiously, if at all. If multiple sources offer the same or similar kinds of evidence, then you can rely on those sources with much more confidence.

5. Purpose: The reason the information exists.

- What is the purpose of the information? Is it to inform, teach, sell, entertain or persuade?

- Do the authors / sponsors make their intentions or purpose clear?

- Is the information fact, opinion or propaganda?

- Does the point of view appear objective and impartial?

- Are there political, ideological, cultural, religious, institutional or personal biases?

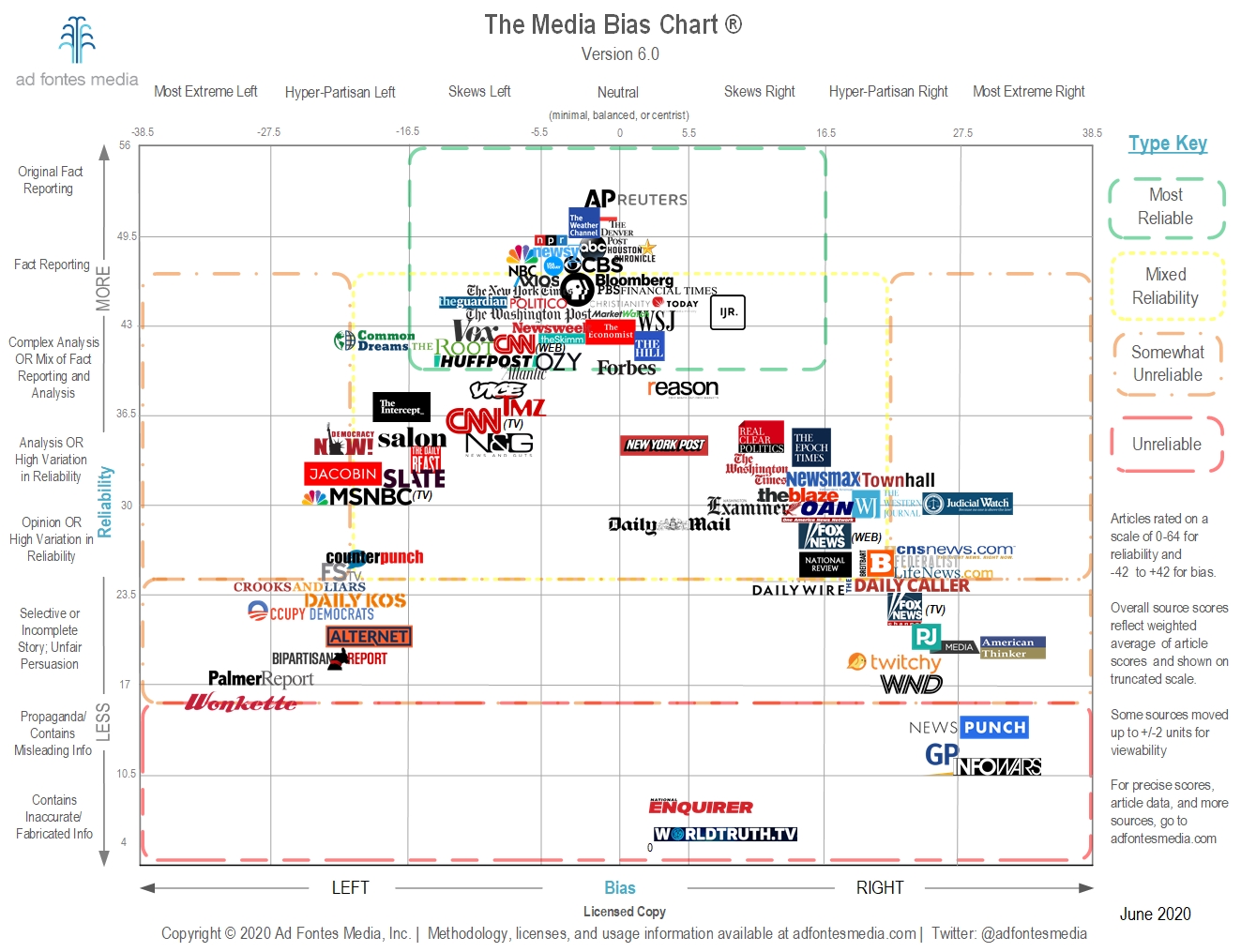

All sources have some bias because authors and publishers have their own ideas and opinions (see Figure 21.2). When you are assessing the bias of a source, consider how much the author or publisher wants the evidence to be true. If it seems like the author or publisher would only accept one kind of answer from the outset (e.g., “climate change is a liberal conspiracy”), the evidence should be considered too biased to be reliable. On the other hand, if the author and publisher seem open to a range of possible conclusions, you can feel more confident about using the source.

TIP: As a researcher, you need to keep your own biases in mind as you assess your sources. Try viewing your sources from alternative perspectives, even perspectives you disagree with. Knowing your own biases and seeing the issue from other perspectives will help you gain a richer understanding of your topic. With that in mind, the following types of sources generally are not acceptable for an academic essay in college, although that depends on the nature of the essay:

- Blogs, podcasts, and anything else that is clearly opinion-based

- Social Media

- Wikis

- Anything with a clear political or religious agenda

The timeliness of source information.

The importance of source information in connection to an essay's needs.

The credibility, qualifications, expertise, and experience of a source's author.

The reliability, truthfulness, and correctness of a source's information.

The goal or objective that the creator of a message is trying to achieve by communicating that message.