24

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Generate content for your memoir. (GEO 1, 4; SLO 4)

- Use the memoir genre to organize a story. (GEO 2; SLO 1, 2)

- Develop an engaging voice to tell your story. (GEO 1, 2; SLO 5)

- Design and add visuals to enhance the narrative. (GEO 2; SLO 3)

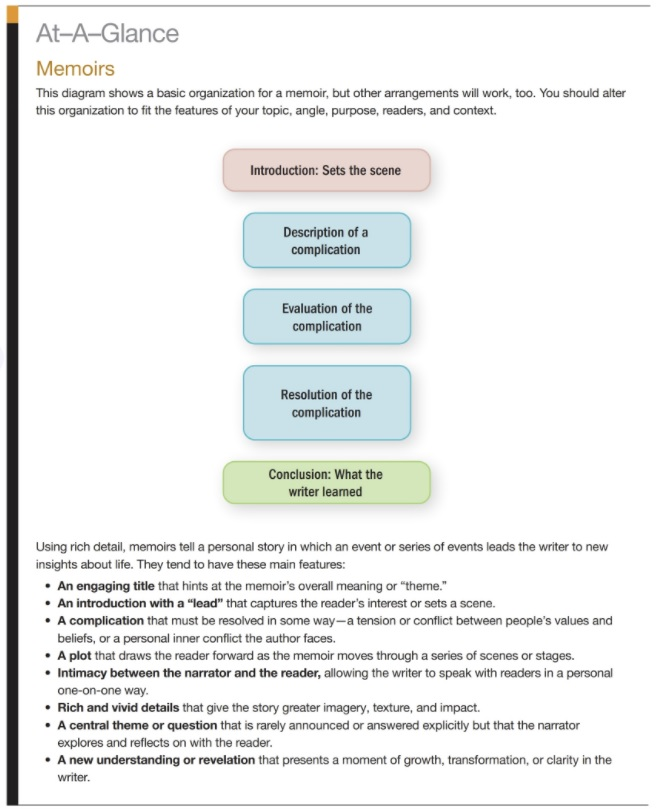

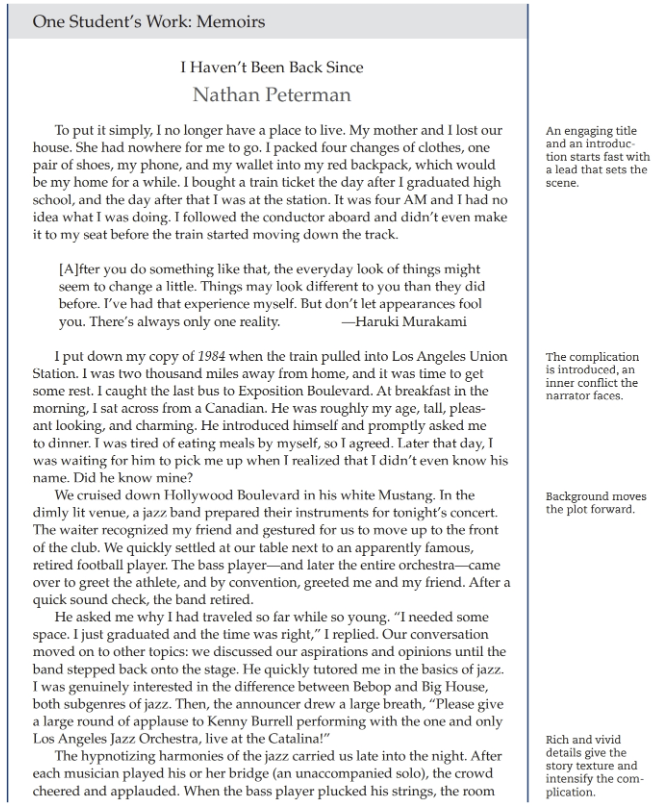

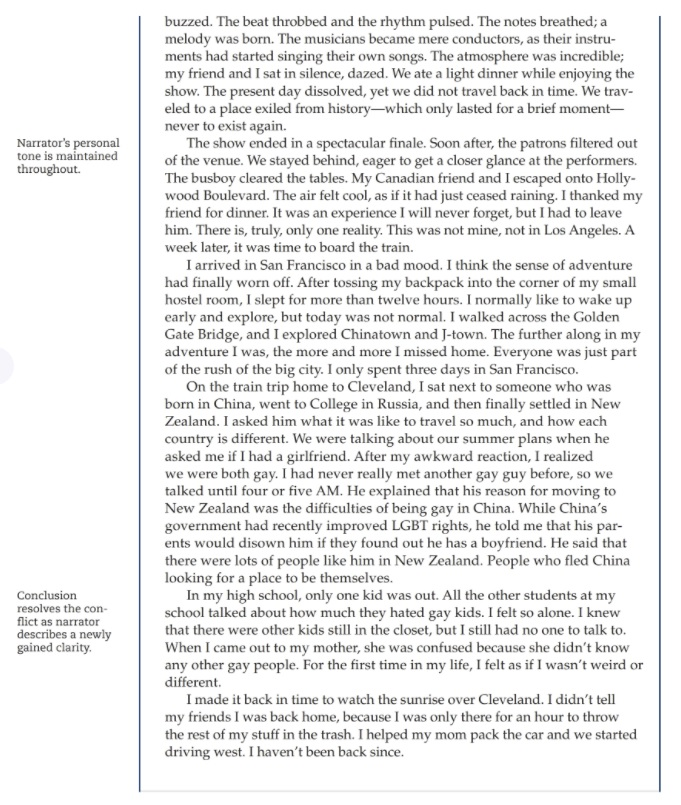

The words memoir and memory come from the same root word. Memoirs, however, do more than allow writers to share their memories. Good memoirs explore and reflect on a central theme or question even though they rarely conclude with explicit answers to those questions. Instead, they invite readers to explore and reflect with the narrator to try to unravel the deeper significance of the recounted events.

People write memoirs when they have true personal stories that they hope will inspire others to reflect on intriguing questions or social issues. Readers expect memoirs to help them encounter perspectives and insights that are fresh and meaningful. Today, memoirs are more popular than ever. They are common on best-seller lists of books, with some recent memoirs selling millions of copies, such as Amy Schumer’s The Girl with the Lower Back Tattoo, which describes her meteoric rise as a comedian, and Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes about his impoverished childhood in Ireland. Meanwhile, blogs and social networking sites give ordinary people opportunities to post reflections on their lives.

In college, professors will sometimes ask you to write about your life to explore your upbringing and discern how you came to hold certain beliefs. In these assignments, the goal is not just to recount events but to unravel their significance and arrive at insights that help you explore and engage more deeply with the issues discussed in the class.

Inventing Your Memoir’s Content

The aim of your memoir is to explore the meaning of an event or series of events from your past. When you start out, don’t be too concerned about the point of your memoir. Instead, choose an interesting incident from your life that you want to explore in greater depth. You want to uncover the meaning of this event for your readers and yourself.

Inquiring: Finding an Interesting Topic

With your whole life as potential subject matter, deciding what to write about and narrowing your topic can be a challenge. Think about the times when you did something challenging, scary, or fun. Think about the times when you felt pain or joy. Think about the times when someone or something important came into your life, helping you make a discovery about yourself. Make a brainstorming list of as many of these events as you can remember (Figure 24.1). Don’t think too much about what you are writing down. These events don’t need to be earth-shattering. Just list the stories you like to tell others about yourself.

Inquiring: Finding Out What You Already Know

Memoirs are about memories—of course—but they include your reflections on those memories. You need to do some personal inquiry to pull up those memories and then reflect on them to figure out what they meant to you at the time and what they mean to you now. Pick an event from your brainstorming list and use some of the following techniques to reflect on it.

Make a map of the scene.

In your mind’s eye, imagine the place where the event happened. Then draw a map of that place (Figure 24.2). Add as many details as you can remember—names, buildings, people, events, landmarks. You can use this map to help you tell your story.

Record your story as a podcast or video.

Tell your story into your computer’s audio recorder or into a camcorder. Afterward, you can transcribe it to the page or screen. Sometimes it’s easier to tell the story orally and then turn it into written text.

Storyboard the event.

In comic strip form, draw out the major scenes in the event. It’s fine to use stick figures, because these drawings are only for you. They will help you recall the details and sort out the story you are trying to tell.

Do some role–playing.

Use your imagination to put yourself into the life of a family member or someone close to you. Try to work through events as that person might have experienced them, even ones that you were part of. Then compare and contrast that person’s experiences with your own, paying special attention to any tensions or conflicts.

Researching: Finding Out What Others Know

Research can help you better understand the event or times you are writing about. For instance, a writer describing her father’s return from a tour in the Iraq War (2003–2011) might want to find out more about the history of this war. She could also find out about soldiers’ experiences by reading personal stories at The Library of Congress Veterans History Project (loc.gov/vets). When researching your topic, try to find information from the following three types of sources:

- Online sources. Use Internet search engines to find information that might help you understand the people or situations in your memoir. Psychology Web sites, for example, might help you explain your own actions or the behavior of others that you witnessed. Meanwhile, historical Web sites might provide background information for an event. This knowledge would help you better recount an experience from a time when you were very young and had little or no awareness of what was happening in the world.

- Print sources. At your campus or public library, look for newspapers or magazines that might have reported something about the event you are describing. Or find historical information in magazines or a history textbook. These resources can help you explain the conditions that shaped how people behaved.

- Empirical sources. Research doesn’t only happen on the Internet and in the library. You should interview people who were involved with the events you will describe in your memoir. If possible, revisit the place you are writing about. Write down any observations, describe things as they are now, and look for details that you might have forgotten or missed.

Organizing and Drafting Your Memoir

To write a good memoir, you will need to go through a series of drafts in order to discover what your theme is, how you want to recount the events, what tone will work best, and so forth. So don’t worry about doing it “correctly” as you write your first, or even your second, draft. Just try to write out your story. When you revise, you can work on figuring out what’s most important and how it all holds together.

Setting the Scene in Rich Detail

At first, you might just describe what happened without worrying too much about the structure of your narrative. Then, once you have the basic series of events written down, start adding details. Give rich descriptions of people, places, and things. Use dialogue to bring your readers into the story.

Main Point or Thesis

Memoirs explore and reflect on a central theme or question, but they rarely provide precise answers or explicit thesis statements. When writing a memoir, put your point in the conclusion, using an implied thesis. In other words, don’t state your main point or thesis in your introduction unless you have a good reason for doing so.

Describing the Complication

The complication in your memoir is the problem or challenge that you or others needed to resolve. So pay special attention to how this complication came about and why you and others first reacted to it as you did.

Evaluating and Resolving the Complication

After describing the characters’ initial reaction, show how you and others evaluated and resolved the complication. The complication isn’t necessarily a problem that needs to be fixed. Instead, you should show how people tried to make sense of the complication, reacted to the change, and moved forward.

Concluding with a Point—an Implied Thesis

Your conclusion describes, directly or indirectly, not only what you learned but also what your reader should have learned from your experiences. Memoirs often have an implied thesis, which means you’re allowing readers to figure out the main point of the story for themselves. In some cases, though, it’s fine to just tell your readers what you learned from the experience.

Examples

Avoid concluding with a “the moral of the story is . . . ” or a “they lived happily ever after” ending. Instead, strive for something that suggests the events or people reached some kind of closure. Achieving closure, however, doesn’t mean stating a high-minded platitude or revealing a fairy tale ending. Instead, give your readers the sense that you and your characters are looking ahead to the future.

Whether you choose to state your main point directly or not, your readers should come away from your memoir with a clear sense of what the story meant to you.

Choosing an Appropriate Style

Choose a style that harmonizes with your story and theme. Your style will create the atmosphere your readers feel and help them identify with your attitude and feelings about the events you are narrating. To make your narrator (you) seem casual, choose a casual style. To set a scene that’s serene, use language that feels calm and quiet.

Evoking an Appropriate Tone or Voice

Tone or voice refers to the attitude, or stance, that you are taking toward your subject matter and your readers. Your tone or voice is the sound your readers will hear as they read your writing. It isn’t something innate to you as a writer. Instead, the tone or voice should fit your topic and your readers.

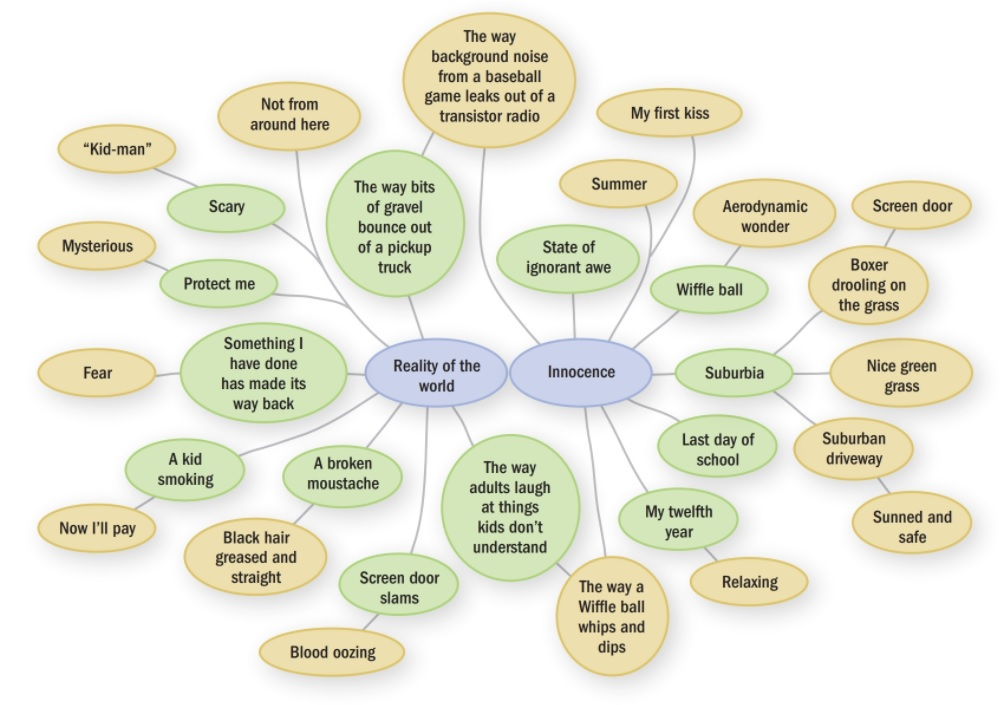

Concept mapping is a useful tool for helping you to set a specific tone and find your voice.

- Think of a keyword that describes the tone you want to set in your memoir.

- Put that word in the middle of your screen or a piece of paper and circle it (Figure 24.3).

- Around that keyword, write down any words or phrases that you tend to associate with this tone word.

- As you put words on the screen or paper, try to come up with more words that are associated with these new words. Hint: you can use your word processor’s thesaurus to help you generate more words.

Eventually, you will fill the screen or sheet. Then, while drafting and revising your memoir, look for places where you can strategically use these words. If you use them consistently throughout the memoir, your readers will sense the tone or attitude you are trying to convey. This tone will help you develop your central “theme,” the idea or question that the entire memoir explores.

Use these words and phrases occasionally and strategically to achieve the effect you want. If you use too many of these words, your readers will sense that you are overdoing it.

Using Dialogue

Allow the characters in your memoir to reveal key details about themselves through dialogue rather than narration. Use dialogue strategically to reveal themes and ideas that are key to understanding your memoir. Here are some guidelines for using dialogue effectively:

Use dialogue to move the story forward.

Reserve dialogue between characters for key moments that move the story forward in an important way. Whenever characters are talking in your memoir, they should reveal something new about themselves or the events happening around them.

Write the way your characters speak.

People rarely speak in proper English. When your characters are talking to each other, use realistic phrasing to show how people really talk. You can use dialects or speech patterns to reveal aspects of your character’s personalities or cultures; however, take care not to slip into dialects that sound stereotypical or even offensive.

Trim the extra words.

In real dialogue, people often say more than they need to say. To avoid drawing out a conversation too much, craft your dialogue to be as crisp and tight as possible.

Identify who is talking.

Your readers should know who is talking, so make sure you use dialogue tags (e.g., he said, she said, he growled, she yelled). Not every statement needs a dialogue tag. If you leave off the tag, make sure it’s obvious who is speaking.

Create unique voices for characters.

Each of your characters should sound different. You can vary their vocabulary, tone, cadence, dialect, or style to give them each a unique voice.

What if you cannot remember what people actually said? As long as you remain true to what you remember, you can invent some of the details of the dialogue.

Designing Your Memoir

Memoirs, like almost all genres today, can use visual design to reinforce the written text. You can augment and deepen your words with images or sound.

Choose the medium.

Readers might be more moved by an audio file of you narrating and enacting your memoir than by a written document. Or perhaps a video or a multimedia document would better allow you to convey your ideas.

Add visuals, especially photos.

Use one or more photos to emphasize a key point, set a tone, or add a new dimension. Photos or drawings of specific places will help your readers visualize where the events in the memoir took place.

Publish your memoir.

Websites like Teen Ink, Buzzfeed, and Slice offer places where you can share your memories. Otherwise, you might consider putting your memoirs on a blog or on your Facebook page. Remember, though, not to reveal private information or photographs that might embarrass you or put you or others at any kind of risk.

Microgenre: The Literacy Narrative

The literacy narrative and digital literacy narrative are memoirs that describe how the author learned to read and write or that focus on some formative experience that involved writing and speaking. Literacy narratives usually have all the elements of other memoirs. They don’t just recount a series of events, but carefully work those events into a plot with a complication. Quite often, the author describes overcoming some obstacle, perhaps the quest for literacy itself or the need to overcome some barrier to learning. Digital literacy narratives are especially popular because they show how authors learned to use new technologies that helped them solve problems in their lives.

Literacy narratives are distinguished from other memoirs by a single feature: they focus on the author’s experiences with reading and writing. Keep in mind that “literacy” encompasses more than learning to read and form letters on the traditional printed page. New writing situations are emerging due to new contexts, readers, purposes, and technologies. Learning to negotiate among these readers, situations, and technologies is the real challenge of becoming literate in today’s world. The definition of literacy is constantly changing. New situations, technologies, and other changes require each of us to continually acquire new literacy skills. All of these challenges are fair game for a literacy narrative.

Literacy narratives should have all the features described in this chapter’s At-A-Glance. Be sure to pay attention to the conflict or tension: What challenge did you face and how did you resolve it—or fail to resolve it? Also, how did the experience change you? What new understanding (positive or negative) did you come away with? And finally, think about the larger theme: What significance does your story have, and what does it tell readers about literacy or what questions does it encourage your readers to reflect on?

Remember that “literacy” includes a broad range of activities, skills, knowledge, and technologies. Choose a significant incident or set of related incidents in your life that involved coming to terms with literacy. Write your literacy narrative or digital literacy narrative as a memoir, paying attention to the memoir’s features. Possible subjects include:

- encountering a new kind of literacy, and the people involved

- working with or helping others with literacy issues

- encountering a new communication technology

- a situation where your literacy skills were tested

- a particular book, work of literature, or other communication that changed your outlook

Memoir Example #1: “My Name” from The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros (1984)

In English my name means hope. In Spanish it means too many letters. It means sadness, it means waiting. It is like the number nine. A muddy color. It is the Mexican records my father plays on Sunday mornings when he is shaving, songs like sobbing.

It was my great-grandmother’s name and now it is mine. She was a horse woman too, born like me in the Chinese year of the horse–which is supposed to be bad luck if you’re born female-but I think this is a Chinese lie because the Chinese, like the Mexicans, don’t like their women strong.

My great-grandmother. I would’ve liked to have known her, a wild, horse of a woman, so wild she wouldn’t marry. Until my great-grandfather threw a sack over her head and carried her off. Just like that, as if she were a fancy chandelier. That’s the way he did it.

And the story goes she never forgave him. She looked out the window her whole life, the way so many women sit their sadness on an elbow. I wonder if she made the best with what she got or was she sorry because she couldn’t be all the things she wanted to be. Esperanza. I have inherited her name, but I don’t want to inherit her place by the window.

At school they say my name funny as if the syllables were made out of tin and hurt the roof of your mouth. But in Spanish my name is made out of a softer something, like silver, not quite as thick as sister’s name Magdalena–which is uglier than mine. Magdalena who at least- – can come home and become Nenny. But I am always Esperanza.

I would like to baptize myself under a new name, a name more like the real me, the one nobody sees. Esperanza as Lisandra or Maritza or Zeze the X. Yes. Something like Zeze the X will do.

Sandra Cisneros (b. 1954) is a poet, short story writer, novelist, essayist, whose work explores the lives of the working-class. Her classic, coming-of-age novel, The House on Mango Street, has sold over six million copies, been translated into over twenty languages, and is required reading in elementary, high school, and universities across the nation. Sandra Cisneros is a dual citizen of the United States and Mexico, and earns her living by her pen.

Memoir Example #2: “Book War” by Wang Ping (Kinship of Rivers 2017)

I discovered “The Little Mermaid” in 1969. That morning, when I opened the door to light the stove to make breakfast, I found my neighbor reading under a streetlight. The red plastic wrap indicated it was Mao [Zedong]’s collected work. She must have been there all night long, for her hair and shoulders were covered with frost, and her body shivered from cold. She was sobbing quietly. I got curious. What kind of person would weep from reading Mao’s words? I walked over and peeked over her shoulders. What I saw made me shiver. The book in her hands was Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales, and she was reading “The Little Mermaid,” the story that had lit my passion for books since kindergarten. I had started school a year earlier so that I could learn how to read the fairy tales by myself. By the end of my first grade, however, the Cultural Revolution began. Schools were closed, libraries sealed. Books, condemned as “poisonous weeds,” were burnt on streets. And I had never been able to get hold of “The Little Mermaid.”

My clever neighbor had disguised Andersen’s “poisonous weed” with the scarlet cover for Mao’s work. Engrossed in the story, she didn’t realize my presence behind her until I started weeping. She jumped up, fairy tales clutched to her budding chest. Her panic-stricken face said she was ready to fight me to death if I dared to report her. We stared at each other for an eternity. Suddenly she started laughing, pointing at my tear-stained face. She knew then that her secret was safe with me.

She gave me 24 hours to read the fairy tales, and I loaned her The Arabian Nights, which was missing the first fifteen pages and the last story. But the girl squealed and started dancing in the twilight. When we finished each other’s books, we started an underground book group with strict rules for safety, and we had books to read every day, all “poisonous” classics.

Soon I excavated a box of books my mother had buried beneath the chicken coop. I pried it open with a screwdriver, and pulled out one treasure after another: The Dream of the Red Chamber, The Book of Songs, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, The Tempest, The Notre Dame, Huckleberry Finn, American Dream, each wrapped with waxed paper to keep out moisture.

I devoured them all, in rice paddies and wheat fields, on my way home from school and errands. I tried to be careful. If I got caught, the consequences would be catastrophic, not only for myself, but also for my entire family. Buy my mother finally discovered I had unearthed her treasure box and set out to destroy these “time bombs” – if I was caught reading these books, the whole family would be destroyed. She combed every possible place in the house: in the deep of drawers, under the mattress and floorboards. It was a hopeless battle: my mother knew every little trick of mine. Whenever she found a book, she’d order me to tear the pages and place them in the stove, and she’d sit nearby watching the words turn into cinder.

When the last book was burnt, I went to the coop to sit with my chickens. Hens and roosters surrounded me, pecking at my closed fists for food. As tears flowed, the Little Mermaid came to me. She stepped onto the sand, her feet bled terribly, and she could not speak, yet how her eyes sang with triumph. Burning with a fever similar to the Little Mermaid’s, I started telling stories to my siblings, friends, and neighbors – stories I’d read from those treasures, stories I made up for myself and my audience. We gathered on summer nights, during winter darkness. When I saw stars rising from their eyes, I knew I hadn’t lost the battle.

The books had been burnt, but the story went on.

Wang Ping (b. 1956) was born in China and came to USA in 1986. She is the founder and director of the Kinship of Rivers project, a five-year project that builds a sense of kinship among the people who live along the Mississippi and Yangtze rivers through exchanging gifts of art, poetry, stories, music, dance and food. With other artists and poets, she has been teaching poetry and art workshops to children and seniors along the river communities, making thousands of flags as gifts to bring to the Mississippi during 2011-12 and to the Yangtze in 2013.

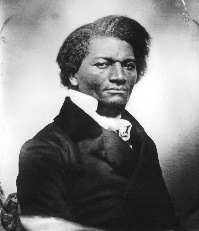

Memoir Example #3: Chapter VII from The Narrative of Frederick Douglass by Frederick Douglass (1845)

I lived in Master Hugh’s family about seven years. During this time, I succeeded in learning to read and write. In accomplishing this, I was compelled to resort to various stratagems. I had no regular teacher.

The plan which I adopted, and the one by which I was most successful, was that of making friends of all the little white boys whom I met in the street. As many of these as I could, I converted into teachers. With their kindly aid, obtained at different times and in different places, I finally succeeded in learning to read. When I was sent of errands, I always took my book with me, and by going one part of my errand quickly, I found time to get a lesson before my return. I used also to carry bread with me, enough of which was always in the house, and to which I was always welcome; for I was much better off in this regard than many of the poor white children in our neighborhood. This bread I used to bestow upon the hungry little urchins, who, in return, would give me that more valuable bread of knowledge.

I was now about twelve years old, and the thought of being a slave for life began to bear heavily upon my heart.

I often found myself regretting my own existence, and wishing myself dead; and but for the hope of being free, I have no doubt but that I should have killed myself, or done something for which I should have been killed. While in this state of mind, I was eager to hear any one speak of slavery. I was a ready listener. Every little while, I could hear something about the abolitionists. It was some time before I found what the word meant. It was always used in such connections as to make it an interesting word to me. If a slave ran away and succeeded in getting clear, or if a slave killed his master, set fire to a barn, or did any thing very wrong in the mind of a slaveholder, it was spoken of as the fruit of abolition.

The light broke in upon me by degrees. I went one day down on the wharf of Mr. Waters; and seeing two Irishmen unloading a scow of stone, I went, unasked, and helped them. When we had finished, one of them came to me and asked me if I were a slave. I told him I was. He asked, “Are ye a slave for life?” I told him that I was. The good Irishman seemed to be deeply affected by the statement. He said to the other that it was a pity so fine a little fellow as myself should be a slave for life. He said it was a shame to hold me. They both advised me to run away to the north; that I should find friends there, and that I should be free. I pretended not to be interested in what they said, and treated them as if I did not understand them; for I feared they might be treacherous. White men have been known to encourage slaves to escape, and then, to get the reward, catch them and return them to their masters. I was afraid that these seemingly good men might use me so; but I nevertheless remembered their advice, and from that time I resolved to run away. I looked forward to a time at which it would be safe for me to escape. I was too young to think of doing so immediately; besides, I wished to learn how to write, as I might have occasion to write my own pass. I consoled myself with the hope that I should one day find a good chance. Meanwhile, I would learn to write.

The idea as to how I might learn to write was suggested to me by being in Durgin and Bailey’s ship-yard, and frequently seeing the ship carpenters, after hewing, and getting a piece of timber ready for use, write on the timber the name of that part of the ship for which it was intended. When a piece of timber was intended for the larboard side, it would be marked thus—”L.” When a piece was for the starboard side, it would be marked thus—”S.” A piece for the larboard side forward, would be marked thus—”L. F.” When a piece was for starboard side forward, it would be marked thus—”S. F.” For larboard aft, it would be marked thus—”L. A.” For starboard aft, it would be marked thus—”S. A.” I soon learned the names of these letters, and for what they were intended when placed upon a piece of timber in the ship-yard. I immediately commenced copying them, and in a short time was able to make the four letters named. After that, when I met with any boy who I knew could write, I would tell him I could write as well as he. The next word would be, “I don’t believe you. Let me see you try it.” I would then make the letters which I had been so fortunate as to learn, and ask him to beat that. In this way I got a good many lessons in writing, which it is quite possible I should never have gotten in any other way. During this time, my copy-book was the board fence, brick wall, and pavement; my pen and ink was a lump of chalk. With these, I learned mainly how to write.

Thus, after a long, tedious effort for years, I finally succeeded in learning how to write.

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) was an escaped slave who became a prominent activist, author and public speaker. He became a leader in the abolitionist movement, which sought to end the practice of slavery, before and during the Civil War. After that conflict and the Emancipation Proclamation of 1862, he continued to push for equality and human rights until his death.

Memoir Example #4: “Words of My Youth” from The Last Street Before Cleveland: An Accidental Pilgrimage by Joe Mackall (2014)

I stand at the edge of my suburban driveway on Fairlawn Drive, sunned and safe. My friend Mick and I play Wiffle ball. Each swing of the bat sends the ball flying into the mystery grip of physics and aerodynamic wonder. The ball appears headed straight up before some hidden hand of wind and speed and serrated plastic jerks it over to the lawn of the widow next door. Mrs. Worth’s boxer drools the day away, watching from the backyard in its own state of ignorant awe.

We take turns “smacking the shit” out of the plastic ball. I don’t notice, not right away, an older kid-a man really-walking down the other side of the street, his eyes straight ahead. Not from around here. As the kid-man gets closer, I focus more intently on the game, as if this focus will protect me from what’s about to happen. I chase the ball as if catching it matters more than anything, more than my first kiss or my last day of school. I make careful throws, keeping my eye on the ball, trying to anticipate the direction of its flight and fall.

I fear-as I so often fear-that something I have done has found its way back to me. And now I’ll pay. Five or six houses away now, the kid-man crosses the street. He’s not from around here, but I recognize him from somewhere. There’s something in the way the kidman never looks around, as if his entire world centers on a horizon only he can see. He’s smoking. Not a good sign. I pick the ball up off the boxer’s drool-wet lawn, wipe the drool on my jeans, and toss it a few feet in the air. When I look up I see the kid-man-black hair greased and straight, a broken mustache, patches of dirt and beard-punch Mick in the nose. Mick bends over and covers his nose with cupped hands in one motion. Blood oozes through his summer-stained fingers and drips onto the hot cement. Although the kidman-eighteen, nineteen, probably-has just punched Mick in the face, I’m stunned stupid when the kid-man walks over to me and slams me in the nose. We run to the porch.

“My girlfriend’s not a dyke” the kid-man says, as he lights a new cigarette from the old and walks off.

It’s true. We have called the man’s girlfriend a dyke. Often and repeatedly. But still, standing behind the harsh-sounding, cool-sounding word with blood dripping from my nose, I who only a minute ago was playing Wiffle ball on a summer afternoon, realize I cannot define nor do I understand the word we all so love to use.

Again on the Wiffle ball driveway, also summer, also my twelfth year, I call one of my Gentile friends a dumb Jew. Soon all of us revel in the discovery of this new slur. This new way of degrading each other catches on quickly. Not one of the Catholic boys schooled in the Judeo-Christian tradition is sure why calling somebody a dumb few is derogatory. But we celebrate this new slur anyway. But wait. Wasn’t Jesus a Jew? Isn’t Bill Rosenberg a Jew? We all love Bill. This must be something else. It sounds different. It sounds like it shouldn’t be said. So we say it and love saying it, we boys without weapons.

The screen door slams. My mother has caught the sound of the slur. She motions for me to come inside. “Tell your friends to go home,” she says. I do not have to. They’re gone. This is 1971, and the suburbs. Somebody’s parent is everybody’s parent. Parents stick together. They know who the real enemy is.

She grabs my hair and pulls me into the house. Inside my head I’m screaming.

I do not say a word.

“What did you say out there? What were you saying?” I understand that my mother knows the answer to her questions. I realize I had better not repeat what I said outside, not even in answer to her questions. I know she never wants to hear that again. Not ever. Not from me. Not from anybody.

“Where did you ever hear a thing like that? That kind of talk?” she asks.

An excellent question. I honestly do not know. I have no idea. The slur just seems to have been out there, there and somehow not there, like incense, Iike the way a Wiffle ball whips and dips, the way adults laugh at things kids don’t understand, the way background noise from a baseball game leaks out of transistor radios, the way bits of gravel bounce out of pickup truck beds, the way factory fires flirt with the night sky, the way sonic booms burst the lie of silence.

Joe Mackall (b. 1959) is an author of books about culture and his own life. In this memoir he talks about growing up in the suburbs. Notice how his voice seems to emerge from the text as he tells his story.

Memoir Example #5: “What’s in a Name?” by Henry Louis Gates Jr. (Dissent Magazine Fall 1989)

“The question of color takes up much space in these pages, but the question of color, especially in this country, operates to hide the graver questions of the self.”

James Baldwin, 1961

“ . . . blood, darky, Tar Baby, Kaffir, shine . . . moor, blackamoor, Jim Crow, spook . . quadroon, meriney, red bone, high yellow . . . Mammy, porch monkey, home, homeboy, George . . . spearchucker, schwarze, Leroy, Smokey . . . mouli, buck. Ethiopian, brother, sistah.”

Trey Ellis, 1989

I had forgotten the incident completely, until I read Trey Ellis’ essay “Remember My Name” in a recent issue of the Village Voice (June 13, 1989). But there, in the middle of an extended italicized list of the bynames of “the race” (“the race” or “our people” being the terms my parents used in polite or reverential discourse, “jigaboo” or “nigger” more commonly used in anger, jest, or pure disgust), it was: “George.” Now the events of that very brief exchange return to mind so vividly that I wonder why I had forgotten it.

My father and I were walking home at dusk from his second job. He “moonlighted” as a janitor in the evenings for the telephone company. Every day but Saturday, he would come home at 3:30 from his regular job at the paper mill, wash up, eat supper, then at 4:30 head downtown to his second job. He used to make jokes frequently about a union official who moonlighted. I never got the joke, but he and his friends thought it was hilarious. All I knew was that my family always ate well, that my brother and I had new clothes to wear, and that all of the white people in Piedmont, West Virginia, treated my parents with an odd mixture of resentment and respect that even we understood at the time had something directly to do with a small but certain measure of financial security.

He had left a little early that evening because I was with him and I had to be in bed early. I could not have been more than five or six, and we had stopped off at the Cut-Rate Drug Store (where no black person in town but my father could sit down to eat, and eat off real plates with real silverware) so that I could buy some caramel ice cream, two scoops in a wafer cone, please, which I was busy licking when Mr. Wilson walked by.

Mr. Wilson was a very quiet man, whose stony, brooding, silent manner seemed designed to scare off any overtures of friendship, even from white people. He was Irish, as was one-third of our village (another third being Italian), the more affluent among whom sent their children to “Catholic School” across the bridge in Maryland. HE had white straight hair, like my Uncle Joe, whom he uncannily resembled, and he carried a black worn metal lunch pail, the kind that Riley [from the 1950s TV program The Life of Riley, about a white, working-class family and their neighbors] carried. My father always spoke to him, and for reasons that we never did understand, he always spoke to my father.

“Hello, Mr. Wilson,” I heard my father say.

“Hello, George.”

I stopped licking my ice cream cone, and asked my Dad in a loud voice why Mr. Wilson had called him George.

“Doesn’t he know your name, Daddy? Why don’t you tell him your name? Your name isn’t George.”

For a moment I tried to think of who Mr. Wilson was mixing Pop up with. But we didn’t have any Georges among the colored people in Piedmont; nor were there colored Georges living in the neighboring towns and working at the mill.

“Tell him your name, Daddy.”

“He knows my name, boy,” my father said after a long pause. “He calls all colored people George.”

A long silence ensued. It was “one of those things,” as my Mom would put it. Even then, that early, I knew when I was in the presence of “one of those things,” one of those things that provided a glimpse, through a rent curtain, at another world that we could not affect but that affected us. There would be a painful moment of silence, and you would wait for it to give way to a discussion of a black superstar such as Sugar Ray or Jackie Robinson.

“Nobody hits better in a clutch than Jackie Robinson.”

“That’s right. Nobody.”

I never again looked Mr. Wilson in the eye.

Henry Louis Gates Jr. (b. 1950) was born in Keyser, West Virginia, and grew up in the small town of Piedmont. Currently the W. E. B. Du Bois Professor of Humanities and Director of the W. E. B. Du Bois Institute for African-American Research at Harvard, he has edited many collections of works by African-American writers and published several volumes of literary criticism. However, he is probably best known as a social critic whose books and articles for a general audience explore a wide variety of issues and themes, often focusing on race and culture. In the following essay, which originally appeared in the journal Dissent, Gates recalls a childhood experience that occurred during the mid-1950s.

Background on the Civil Rights movement: In the mid-1950s, the first stirrings of the civil rights movement were underway, and in 1954 and 1955 the U.S. Supreme Court handed down decisions declaring racial segregation unconstitutional in public schools. Still, much of the country – particularly the South – remained largely segregated until Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination based on race, color, religious, or national origin in businesses covered by interstate commerce laws, as well as in employment. This was followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which guaranteed equal access to the polls, and the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which prohibited discrimination in housing and real estate. At the time of the experience Gates recalls here – before these laws were enacted – prejudice and discrimination against African-Americans were the norm in many communities, even those outside the South.

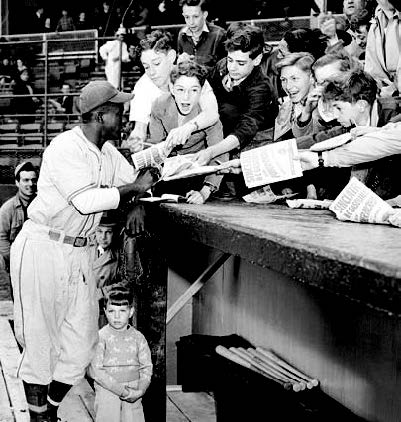

Memoir Example #6: “The Noble Experiment” from I Never Had It Made by Jackie Robinson, as told to Alfred Duckett (1972)

In 1910 Branch Rickey was a coach for Ohio Wesleyan. The team went to South Bend, Indiana, for a game. The hotel management registered the coach and team but refused to assign a room to a black player named Charley Thomas. In those days college ball had a few black players. Mr. Rickey took the manager aside and said he would move the entire team to another hotel unless the black athlete was accepted. The threat was a bluff because he knew the other hotels also would have refused accommodations to a black man. While the hotel manager was thinking about the threat, Mr. Rickey came up with a compromise. He suggested a cot be put in his own room, which he would share with the unwanted guest. The hotel manager wasn’t happy about the idea, but he gave in.

Years later Branch Rickey told the story of the misery of that black player to whom he had given a place to sleep. He remembered that Thomas couldn’t sleep.

“He sat on that cot,” Mr. Rickey said, “and was silent for a long time. Then he began to cry, tears he couldn’t hold back. His whole body shook with emotion. I sat and watched him, not knowing what to do until he began tearing at one hand with the other—just as if he were trying to scratch the skin off his hands with his fingernails. I was alarmed. I asked him what he was trying to do to himself.

“‘It’s my hands,’ he sobbed. ‘They’re black. If only they were white, I’d be as good as anybody then, wouldn’t I, Mr. Rickey? If only they were white.’”

“Charley,” Mr. Rickey said, “the day will come when they won’t have to be white.”

Thirty-five years later, while I was lying awake nights, frustrated, unable to see a future, Mr. Rickey, by now the president of the Dodgers, was also lying awake at night, trying to make up his mind about a new experiment.

He had never forgotten the agony of that black athlete. When he became a front-office executive in St. Louis, he had fought, behind the scenes, against the custom that consigned black spectators to the Jim Crow section of the Sportsman’s Park, later to become Busch Memorial Stadium. His pleas to change the rules were in vain. Those in power argued that if blacks were allowed a free choice of seating, white business would suffer.

Branch Rickey lost that fight, but when he became the boss of the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1943, he felt the time for equality in baseball had come. He knew that achieving it would be terribly difficult. There would be deep resentment, determined opposition, and perhaps even racial violence. He was convinced he was morally right, and he shrewdly sensed that making the game a truly national one would have healthy financial results. He took his case before the startled directors of the club, and using persuasive eloquence, he won the first battle in what would be a long and bitter campaign. He was voted permission to make the Brooklyn club the pioneer in bringing blacks into baseball.

Winning his directors’ approval was almost insignificant in contrast to the task which now lay ahead of the Dodger president. He made certain that word of his plans did not leak out, particularly to the press. Next, he had to find the ideal player for his project, which came to be called “Rickey’s noble experiment.” This player had to be one who could take abuse, name-calling, rejection by fans and sportswriters and by fellow players not only on opposing teams but on his own. He had to be able to stand up in the face of merciless persecution and not retaliate. On the other hand, he had to be a contradiction in human terms; he still had to have spirit. He could not be an “Uncle Tom.” His ability to turn the other cheek had to be predicated on his determination to gain acceptance. Once having proven his ability as player, teammate, and man, he had to be able to cast off humbleness and stand up as a full-fledged participant whose triumph did not carry the poison of bitterness.

Unknown to most people and certainly to me, after launching a major scouting program, Branch Rickey had picked me as that player. The Rickey talent hunt went beyond national borders. Cuba, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, and other countries where dark-skinned people lived had been checked out. Mr. Rickey had learned that there were a number of black players, war veterans mainly, who had gone to these countries, despairing of finding an opportunity in their own country. The manhunt had to be camouflaged. If it became known he was looking for a black recruit for the Dodgers, all hell would have broken loose. The gimmick he used as a cover-up was to make the world believe that he was about to establish a new Negro league. In the spring of 1945 he called a press conference and announced that the Dodgers were organizing the United States League, composed of all black teams. This, of course, made blacks and pro-integration whites indignant. He was accused of trying to uphold the existing segregation and, at the same time, capitalize on black players. Cleverly, Mr. Rickey replied that his league would be better organized than the current ones. He said its main purpose, eventually, was to be absorbed into the majors. It is ironic that by coming very close to telling the truth, he was able to conceal that truth from the enemies of integrated baseball. Most people assumed that when he spoke of some distant goal of integration, Mr. Rickey was being a hypocrite on this issue as so many of baseball’s leaders had been.

Black players were familiar with this kind of hypocrisy. When I was with the Monarchs, shortly before I met Mr. Rickey, Wendell Smith, then sports editor of the black weekly Pittsburgh Courier, had arranged for me and two other players from the Negro league to go to a tryout with the Boston Red Sox. The tryout had been brought about because a Boston city councilman had frightened the Red Sox management. Councilman Isadore Muchneck threatened to push a bill through banning Sunday baseball unless the Red Sox hired black players. Sam Jethroe of the Cleveland Buckeyes, Marvin Williams of the Philadelphia Stars, and I had been grateful to Wendell for getting us a chance in the Red Sox tryout, and we put our best efforts into it. However, not for one minute did we believe the tryout was sincere. The Boston club officials praised our performance, let us fill out application cards, and said, “So long.” We were fairly certain they wouldn’t call us, and we had no intention of calling them.

Incidents like this made Wendell Smith as cynical as we were. He didn’t accept Branch Rickey’s new league as a genuine project, and he frankly told him so. During this conversation, the Dodger boss asked Wendell whether any of the three of us who had gone to Boston was really good major league material. Wendell said I was. I will be forever indebted to Wendell because, without his even knowing it, his recommendation was in the end partly responsible for my career. At the time, it started a thorough investigation of my background.

In August 1945, at Comiskey Park in Chicago, I was approached by Clyde Sukeforth, the Dodger scout. Blacks have had to learn to protect themselves by being cynical but not cynical enough to slam the door on potential opportunities. We go through life walking a tightrope to prevent too much disillusionment. I was out on the field when Sukeforth called my name and beckoned. He told me the Brown Dodgers were looking for top ballplayers, that Branch Rickey had heard about me and sent him to watch me throw from the hole. He had come at an unfortunate time. I had hurt my shoulder a couple of days before that, and I wouldn’t be doing any throwing for at least a week.

Sukeforth said he’d like to talk with me anyhow. He asked me to come to see him after the game at the Stevens Hotel.

Here we go again, I thought. Another time-wasting experience. But Sukeforth looked like a sincere person, and I thought I might as well listen. I agreed to meet him that night. When we met, Sukeforth got right to the point. Mr. Rickey wanted to talk to me about the possibility of becoming a Brown Dodger. If I could get a few days off and go to Brooklyn, my fare and expenses would be paid. At first I said that I couldn’t leave my team and go to Brooklyn just like that. Sukeforth wouldn’t take no for an answer. He pointed out that I couldn’t play for a few days anyhow because of my bum arm. Why should my team object?

I continued to hold out and demanded to know what would happen if the Monarchs fired me. The Dodger scout replied quietly that he didn’t believe that would happen.

I shrugged and said I’d make the trip. I figured I had nothing to lose.

Branch Rickey was an impressive-looking man. He had a classic face, an air of command, a deep, booming voice, and a way of cutting through red tape and getting down to basics. He shook my hand vigorously and, after a brief conversation, sprang the first question.

“You got a girl?” he demanded.

It was a hell of a question. I had two reactions: why should he be concerned about my relationship with a girl; and, second, while I thought, hoped, and prayed I had a girl, the way things had been going, I was afraid she might have begun to consider me a hopeless case. I explained this to Mr. Rickey and Clyde.

Mr. Rickey wanted to know all about Rachel. I told him of our hopes and plans.

“You know, you have a girl,” he said heartily. “When we get through today, you may want to call her up because there are times when a man needs a woman by his side.”

My heart began racing a little faster again as I sat there speculating. First he asked me if I really understood why he had sent for me. I told him what Clyde Sukeforth had told me.

“That’s what he was supposed to tell you,” Mr. Rickey said. “The truth is you are not a candidate for the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers. I’ve sent for you because I’m interested in you as a candidate for the Brooklyn National League Club. I think you can play in the major leagues. How do you feel about it?”

My reactions seemed like some kind of weird mixture churning in a blender. I was thrilled, scared, and excited. I was incredulous. Most of all, I was speechless.

“You think you can play for Montreal?” he demanded.

I got my tongue back. “Yes,” I answered.

Montreal was the Brooklyn Dodgers’ top farm club. The players who went there and made it had an excellent chance at the big time.

I was busy reorganizing my thoughts while Mr. Rickey and Clyde Sukeforth discussed me briefly, almost as if I weren’t there. Mr. Rickey was questioning Clyde. Could I make the grade?

Abruptly, Mr. Rickey swung his swivel chair in my direction. He was a man who conducted himself with great drama. He pointed a finger at me.

“I know you’re a good ballplayer,” he barked. “What I don’t know is whether you have the guts.”

I knew it was all too good to be true. Here was a guy questioning my courage. That virtually amounted to him asking me if I was a coward.

Mr. Rickey or no Mr. Rickey, that was an insinuation hard to take. I felt the heat coming up into my cheeks.

Before I could react to what he had said, he leaned forward in his chair and explained.

I wasn’t just another athlete being hired by a ball club. We were playing for big stakes. This was the reason Branch Rickey’s search had been so exhaustive. The search had spanned the globe and narrowed down to a few candidates, then finally to me. When it looked as though I might be the number-one choice, the investigation of my life, my habits, my reputation, and my character had become an intensified study.

“I’ve investigated you thoroughly, Robinson,” Mr. Rickey said.

One of the results of this thorough screening were reports from California athletic circles that I had been a “racial agitator” at UCLA. Mr. Rickey had not accepted these criticisms on face value. He had demanded and received more information and came to the conclusion that if I had been white, people would have said, “Here’s a guy who’s a contender, a competitor.”

After that he had some grim words of warning. “We can’t fight our way through this, Robinson. We’ve got no army. There’s virtually nobody on our side. No owners, no umpires, very few newspapermen. And I’m afraid that many fans will be hostile. We’ll be in a tough position. We can win only if we can convince the world that I’m doing this because you’re a great ballplayer and a fine gentleman.”

He had me transfixed as he spoke. I could feel his sincerity, and I began to get a sense of how much this major step meant to him. Because of his nature and his passion for justice, he had to do what he was doing. He continued. The rumbling voice, the theatrical gestures were gone. He was speaking from a deep, quiet strength.

“So there’s more than just playing,” he said. “I wish it meant only hits, runs, and errors—only the things they put in the box score. Because you know—yes, you would know, Robinson, that a baseball box score is a democratic thing. It doesn’t tell how big you are, what church you attend, what color you are, or how your father voted in the last election. It just tells what kind of baseball player you were on that particular day.”

I interrupted. “But it’s the box score that really counts—that and that alone, isn’t it?”

“It’s all that ought to count,” he replied. “But it isn’t. Maybe one of these days it will be all that counts. That is one of the reasons I’ve got you here, Robinson. If you’re a good enough man, we can make this a start in the right direction. But let me tell you, it’s going to take an awful lot of courage.”

He was back to the crossroads question that made me start to get angry minutes earlier. He asked it slowly and with great care.

“Have you got the guts to play the game no matter what happens?”

“I think I can play the game, Mr. Rickey,” I said.

The next few minutes were tough. Branch Rickey had to make absolutely sure that I knew what I would face. Beanballs6would be thrown at me. I would be called the kind of names which would hurt and infuriate any man. I would be physically attacked. Could I take all of this and control my temper, remain steadfastly loyal to our ultimate aim?

He knew I would have terrible problems and wanted me to know the extent of them before I agreed to the plan. I was twenty-six years old, and all my life—back to the age of eight when a little neighbor girl called me names—I had believed in payback, retaliation. The most luxurious possession, the richest treasure anybody has, is his personal dignity. I looked at Mr. Rickey guardedly, and in that second I was looking at him not as a partner in a great experiment, but as the enemy—a white man.

I had a question, and it was the age-old one about whether or not you sell your birthright.

“Mr. Rickey,” I asked, “are you looking for a Negro who is afraid to fight back?”

I never will forget the way he exploded.

“Robinson,” he said, “I’m looking for a ballplayer with guts enough not to fight back.”

After that, Mr. Rickey continued his lecture on the kind of thing I’d be facing.

He not only told me about it, but he acted out the part of a white player charging into me, blaming me for the “accident” and calling me all kinds of foul racial names. He talked about my race, my parents, in language that was almost unendurable.

“They’ll taunt and goad you,” Mr. Rickey said. “They’ll do anything to make you react. They’ll try to provoke a race riot in the ballpark. This is the way to prove to the public that a Negro should not be allowed in the major league. This is the way to frighten the fans and make them afraid to attend the games.”

If hundreds of black people wanted to come to the ballpark to watch me play and Mr. Rickey tried to discourage them, would I understand that he was doing it because the emotional enthusiasm of my people could harm the experiment? That kind of enthusiasm would be as bad as the emotional opposition of prejudiced white fans.

Suppose I was at shortstop. Another player comes down from first, stealing, flying in with spikes high, and cuts me on the leg. As I feel the blood running down my leg, the white player laughs in my face.

“How do you like that, boy?” he sneers.

Could I turn the other cheek? I didn’t know how I would do it. Yet I knew that I must. I had to do it for so many reasons. For black youth, for my mother, for Rae, for myself. I had already begun to feel I had to do it for Branch Rickey.

I was offered, and agreed to sign later, a contract with a $3,500 bonus and $600-a-month salary. I was officially a Montreal Royal. I must not tell anyone except Rae and my mother.

Jackie Robinson (1919–1972) was the first man at the University of California, Los Angeles, to earn varsity letters in four sports. He then went on to play professional baseball in 1945 in the Negro Leagues. His talent and extraordinary character were quickly noticed. In 1947, he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers. Robinson was honored as Rookie of the Year in 1947 and National League Most Valuable Player in 1949. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962. With the help of his wife, Rachel, Jackie paved the way for African-American athletes.

Robinson worked on his autobiography with Alfred Duckett, a writer and baseball fan. Active in the civil rights movement, Duckett was a speechwriter for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Segregated National Pastime: In the 1940s, African-Americans faced many barriers. Segregation kept African Americans separate from whites in every part of society, including sports. In baseball the Negro League was completely separate from the all-white teams of the Major League. Jackie Robinson would help change that.

A nonfiction narrative based in the author's personal memories.

The broad idea or issue that a message deals with.

An informal way of generating ideas to write about or points to make about your topic.

Drawing a set of pictures that show the progression of your ideas.

Sources that require an Internet connection and/or electronic device (computer, DVD player, radio, television, etc.) to access. For example: websites, podcasts, videos, movies, television shows, audio recordings.

Sources that were originally intended to be accessed and read in physical, printed form. For example: books, newspapers, magazines, journals, newsletters, other periodicals or publications.

Source material that was collected by the researcher and analyzed for research purposes. For example: Personal experiences, field observations, interviews, surveys, case studies, experiments.

A conversation between two or more characters, noted with quotation marks.

A central topic, subject, or message within a narrative.

The main idea, point, or claim of a written work. Plural: theses.

The last paragraph in an academic essay that generally summarizes the essay, presents the main idea of the essay, or gives an overall solution to a problem or argument given in the essay.

A situation or detail of a character that complicates the main thread of a plot and presents a challenge, choice, or conflict.

The general feeling or attitude of a piece of writing.

The rhetorical mixture of vocabulary, tone, point of view, and syntax that makes phrases, sentences, and paragraphs flow in a particular manner.

A diagram that depicts suggested relationships between concepts.

The process of telling a story using sequence of events and description.

Traditionally, literacy is defined as the ability to read and write. Today, UNESCO defines literacy as "an ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts." Contemporary social linguistics studies interpret as a "context-dependent assemblage of social practices," which reflects the understanding that individuals' reading and writing practices develop and change over the lifespan as their cultural, political, and historical contexts change.