25

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Invent the content for your profile. (GEO 1, 4; SLO 4)

- Organize and draft your profile in an attention-grabbing way. (GEO 2; SLO 1, 2)

- Choose a style that captures the essence of your topic. (GEO 1, 2; SLO 5)

- Design your profile to fit the place where it will be used. (GEO 2; SLO 3)

Profiles are used to describe interesting people, places, and events. They are used to create a sketch of a person, place, or event by viewing the subject from a specific angle. Profiles often reveal something essential through a story or series of stories—an insight, idea, theme, or social cause. Some of the best profiles focus on people, places, or events that seem ordinary but are symbolic of larger issues. Most profiles are written about people, but places and events can offer interesting topics, too. For example, you could profile a specific place in your hometown, a unique building, or a whole town, describing it as a living being. Or you might write a profile of an event (e.g., a basketball game, a protest, a historical battle, an earthquake) in a way that makes the subject come alive. Profiles appear in a variety of print and online publications. They are common in print magazines like People, Rolling Stone, and Sports Illustrated. They are also regularly published on Web sites like Slate.com, National Review Online, and Politico. Profiles are also mainstays on cable channels like ESPN, A&E, and the Biography Channel. In college and in your career, you will write profiles for Web sites, brochures, reports, and proposals. Profiles are also called backgrounders and bios, and they appear on corporate Web sites under headings or links such as “About Us” or “Our Team.” You may also want to write your own profile for social networking sites like Facebook, Instagram, or LinkedIn.

Inventing Your Profile’s Content

Start out by choosing a person, place, or event that you can easily access. If you are profiling a person, choose someone you can shadow, interview, or research as the subject for your profile. Or, if you are writing a profile of an historic figure or a celebrity, find someone whose life and times you are interested in exploring. If you are writing a profile of a place or event, choose something that you can portray as a living being, which moves, has emotions, and is changing in an interesting way. Make sure you find a subject that is fascinating to you, because if you are not interested, you will find it very difficult to spark your readers’ interest.

Inquiring: Finding Out What You Already Know

Take some time to think about what makes this person, place, or event unique or interesting. Try to develop an angle that will depict your topic in a way that makes your pro-file thought-provoking and meaningful. Use one or more invention methods to generate ideas for your profile. Here are a couple of especially good invention tools for profiles.

- Answer the five-w and how questions. Journalists often use the Five-W and How questions (heurisitics) to get started.

- Who? Who exactly is this person? What’s the nature of this place or event? Who has influenced the subject of your profile, and who has he or she influenced? Who is regularly involved with this person?

- What? What exactly are you profiling? What does the person, place, or event look like? What is unique about this person, place, or event? What has your subject done that is especially interesting to you and your readers?

- Where? Where did this person come from? Where is this person now? Where did important events happen? Where did the events start and end?

- When? When did the major events in the profile happen? When did the story begin? When did it end, or when will it probably end?

- Why? Why did this person or others behave as they did? Why has this person, event, or organization succeeded or failed? Why has your subject changed in a significant way?

- How? How did this person’s background shape his or her outlook on life? How does your subject respond to people and events? How will this person, organization, place, or event be understood or misunderstood in the future?

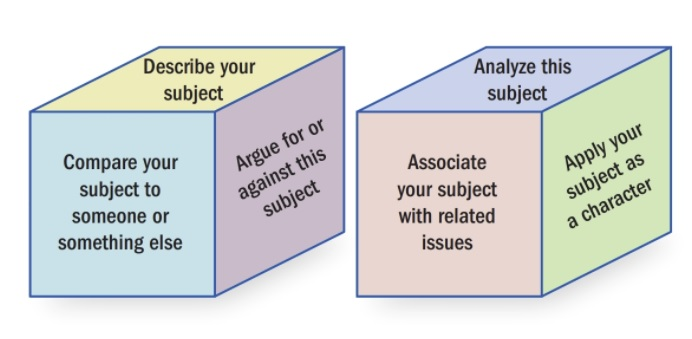

- Use cubing. Cubing allows you to explore your topic from six different viewpoints or perspectives (Figure 25.1). Describe your subject by paying attention to your senses.

- Compare your subject to someone or something else. Associate this subject with related issues or things you already know about. Analyze this subject, looking for any patterns, hidden questions, or unique characteristics. Apply your subject as a character by describing it in action. Argue for or against: Is this person or group of people right or wrong, a saint or a scoundrel, or has this place helped bring about good or bad results?

Researching: Finding Out What Others Know

Good research is essential to writing an interesting profile. You should begin by idetifying a variety of online, print, and empirical sources.

- Online Sources. Use an Internet search engine to gather biographical or historical information on this person, place, or event. Then gather background information on the time period you are writing about.

- Print Sources. Consult newspapers, magazines, and books. These print sources are probably available at your campus library or a local public library.

- Empirical Sources. Interview your subject and/or talk to people who can provide firsthand knowledge or experience about this person, place, or event. You might also ask whether you can observe or even shadow him or her. For a profile about a place or an event, you can interview people who live in the place you are profiling or who experienced the event you are writing about.

- Interviewing. An interview is often the best way to gather information for a profile. If possible, do your interviews in person. If that’s not possible, phone calls or e-mails are often good ways to ask people questions about themselves or others. Remember to script your questions before your interview. Then, while conducting the interview, be sure to listen and respond—asking follow-up questions that engage with what the interviewee has told you.

- Shadowing. If the subject of your profile is a person, you could “shadow” him or her (with the person’s permission, of course), learning more about that person’s world, the people in it, and how he or she interacts with them. For a place or event profile, spend some time exploring and observing, either by visiting the physical location or examining pictures and firsthand accounts. Keep your notebook, a camera, and perhaps a digital recorder handy to capture anything that might translate into an interesting angle or a revealing quotation. In Section III: Research, you can learn more about interviewing and other empirical forms of research.

Organizing and Drafting Your Profile

A well-organized profile will capture the attention of readers and keep it. As you organize your ideas and write your first draft, keep these key questions in mind: What do you find most interesting, surprising, or important? As you researched your subject, what did you discover that you weren’t expecting? How can you make this discovery interesting for your readers? What important conflicts does your subject face? People are most interesting when they face important challenges. Similarly, places and events are scenes of conflict and change. What is the principal conflict for your subject?

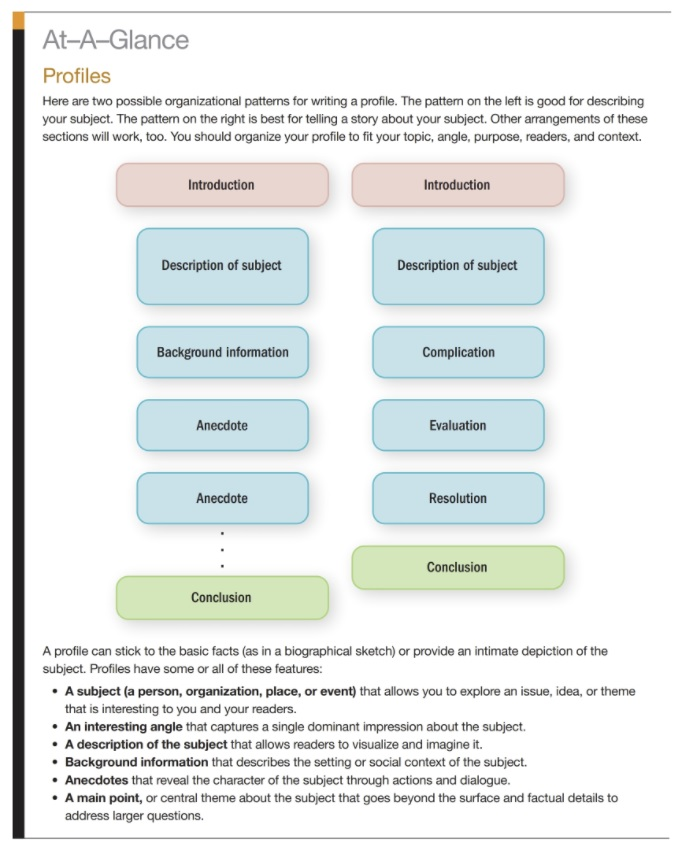

Keep in mind that the profile is one of the most flexible genres. You can arrange the information you collected in a variety of ways to suit your topic, purpose, and readers and the contexts in which they will read the profile.

The Introduction

You want to start strong with a lead that hints at or captures the main point of the profile.

Identify your topic and purpose. Your introduction should identify the subject of your profile, while directly or indirectly revealing your purpose. You might also want to show readers why the person, place, or event you are profiling is significant in some way.

State your main point or thesis. The placement of your main point (thesis) depends on the type of profile you are writing. In a descriptive profile, you can state your main point, or thesis, in the introduction. Tell your readers upfront what you are trying to show about your subject. In a narrative profile, you probably won’t state your main point or thesis in the introduction. Instead, you should wait until the conclusion to reveal your overall point.

The Body

In the body, you can include a variety of moves such as describing your topic, offering background information, recounting anecdotes, or revealing important ideas through dialogue.

Describe your topic. Use plenty of details to describe how your subject looks, moves, and sounds. In some situations, you might use your full senses to describe your subject’s environment, including how things smell, sound, and feel.

Offer background on the topic. You can tell your readers something about the time periods and places in which your subject lived or lives now. Explore the circumstances that led to key events you describe in your profile.

Use anecdotes to tell stories. An anecdote is a small story that reveals something important about a person or a place. Your anecdotes should also reflect the main point of your profile by revealing something important about your subject.

Reveal important information through dialogue or quotes. Dialogue and quotes are often the best way to reveal something important about the topic of your profile without coming out and stating something directly. However, don’t overuse dialogue or quotes. Because quotes receive special attention from readers, reserve them for insights or changes that are especially important.

The Conclusion

Profiles shouldn’t just end; they should leave your readers with an impression. Your readers will give your conclusion special attention because they will expect you to reveal the point you want them to take away from the profile. Conclude with a strong impression that will stay with your readers. You should also keep your conclusion brief. State or restate your main point (your thesis) with emphasis. If you included a thesis statement in your introduction, phrase your main point differently here. Then offer a look at the future in which you say something about what lies ahead for the person, place, or event you profiled.

Choosing an Appropriate Style

If possible, the style of your profile should reflect the essential character of the person, place, or event you are describing. If you are profiling an exciting or restless person, you want your tone or voice to be equally exciting and energetic. If you are profiling someone or something sad or dour, again, your profile’s tone or voice should match that feeling.

Change the pace. If you want to convey energy and spirit, speed up the pace by using abrupt, short sentences and phrases that will increase the heartbeat of the text. If you want your readers to sense a slower pace or thoughtfulness, you can use longer sentences that slow things down. All sentences, however, should be “breathing length,” which means they can be read out loud comfortably in one breath.

Choose words that set a specific tone. Think of one word or phrase that captures the main feeling or attitude you want to express about the subject of your profile. Do you want to convey a sense of joy, sadness, energy, devotion, goodwill, seriousness, or anxiety? Pick a word and then use brainstorming or concept mapping to come up with more words and phrases that associate with that word. You can then seed those words and phrases into your profile to create this specific tone or feeling.

Get into character. You might find the best way to develop a specific voice or tone is to inhabit the character of the person, place, or event you are profiling. Imagine you are that person (or at the place or event). From this different perspective, how would you describe the people, objects, and happenings around you? Are you amped up? Are you anxious or scared? Are you worried? Use words that fit this character.

Designing Your Profile

Profiles usually take on the design of the medium (e.g., magazine, newspaper, Web site, television documentary) in which they will appear. A profile written for a magazine or newspaper will look different than a profile written to go with a report or proposal. So as you think about the appropriate design for your profile, consider what will work with the medium in which it will appear.

Use headings. Your readers may be looking for specific information about the person, place, or event you are profiling. Headings will allow you to reveal how your profile is organized, while helping your readers locate the information they need.

Add photographs. When writing for any medium, consider using photographs, especially images that reflect the profile’s main point. If possible, try to find photographs that capture the look or characteristic you are trying to convey. Then use captions to explain each picture and reinforce the profile’s point.

Include pull quotes or breakouts. Readers often skim profiles to see if the topic interests them. You want to stop them from skimming by giving them an access point into the text. One way to catch their attention is to use a pull quote or breakout that quotes something from the text. Pull quotes appear in a large font and are usually placed in the margins or a gap in the text. These kinds of quotes will grab the readers’ attention and encourage them to start reading.

Microgenre: The Portrait

A portrait is a snapshot that attempts to reveal a person’s inner nature. In photography and painting, portraits do more than describe how someone looks. They capture the feeling and emotion of a person in an instant.

Similarly, a written portrait is a visual description that offers insights into someone’s inner being. When writing this kind of profile, you are trying to describe your subject in a way that reveals her or his true personality without coming out and telling the readers directly what that personality is.

In your college classes, you may be asked to write portraits of people you know or meet, as well as prominent people, such as famous scientists, political figures, and revolutionaries. In literature classes, you may be asked to write about fictional protagonists and villains. You may also enjoy writing portraits of musicians, sports figures, actors, and fictional characters for popular Web sites. A portrait is a good way to explore someone else’s personality, characteristics, and motives.

When writing a portrait, pay attention to how that person looks or presents herself or himself to others. Pay attention to how this person moves or interacts with others. Look for those moments in which the person behind the mask is revealed and try to capture that moment in descriptive detail. Keep in mind that the best portraits in photography and painting capture something “true” that lies beneath the surface. The same is true of a written portrait.

Set the scene. Portraits are usually stories, so your first task is to set the scene. Describe the place and time in which you are describing your subject.

Describe your subject. Describe your subject within that scene. A detailed visual description is common, but you can also use sound, smell, and touch to add other qualities for your readers to experience.

Add a complication. People best reveal themselves when they are dealing with a conflict. Show this per-son being challenged in some way. The complication can be a small thing. In fact, people often reveal their true selves in unguarded moments when they are trying to solve a small problem. Provide the basic biographical facts. If appropriate, offer the subject’s name, age, and other relevant biographical details.

Concentrate on the subject’s face. Like a photographic portrait, the face is the focal point of a written portrait. The face is where subjects will reveal their emotions and tensions. Describe those moments for your readers through your subject’s face.

Put your subject in motion. Photographic portraits are still, but give a sense of motion. Written portraits should also put the subject in motion, showing how she or he moves and interacts with others and the scene.

Use dialogue. People often reveal themselves as they talk. Use quotes from your subject that reveal the quality you are trying to capture.

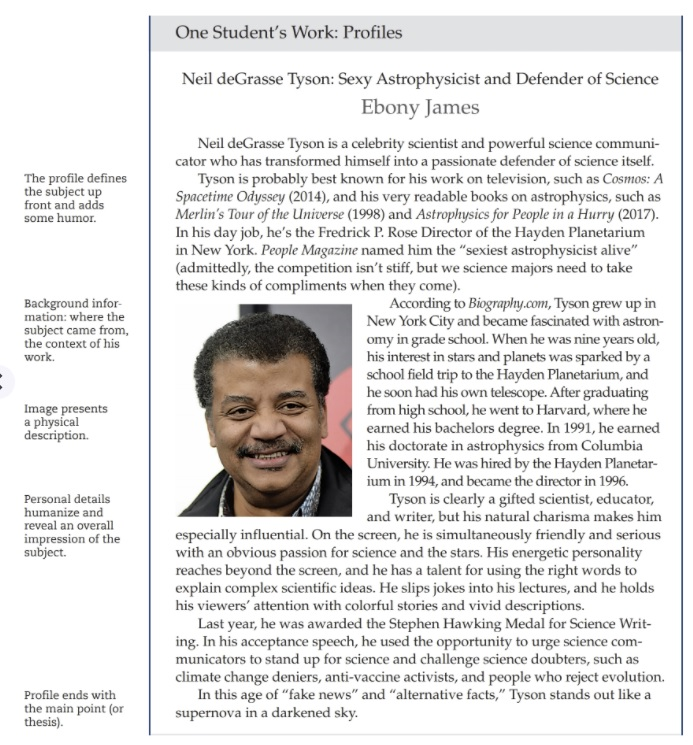

“Beyoncé Brought the Feminine Divine to the Grammys” by Hannah Giorgis

Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter is first and foremost the daughter of Celestine. And it was “with a mother’s pride” that Ms. Tina herself introduced her daughter’s celestial performance only an hour into Sunday’s Grammys. With shades of gold and yellow radiating out from the stage where she stood, Beyoncé channeled the sacred femininity she has long celebrated. But tonight, in her first performance since announcing her pregnancy on February 1, the icon insisted women are not simply powerful—we are divine.

In a monochromatic gold outfit that made [the] Staples Center disappear behind her, Beyoncé looked regal. The intricate crown atop her head, adorned with both spikes and roses, was equal parts arresting and angelic. It recalled the ethereal headpiece her sister Solange wore in her Saturday Night Live performance in November, but with a protective edge. With its juxtaposition of floral fragility and thorned weaponry, Beyoncé’s halo befit the woman who appeared onstage to the sounds of British-Somali poet Warsan Shire: “Women like her cannot be contained.”

The performance itself was lavish, engrossing, otherworldly; but it still felt grounded in the way an Octavia Butler novel does: futuristic but familiar. Flanked by dozens of black women whose gold accents shone in harmony with her own gold attire, Beyoncé drew from some of Lemonade’s most powerful imagery: scenes of black women in sync with one another, dancing, swaying, being. Their bodies moved as a wave underneath her. When her gold throne tilted so far back it seemed it would rupture the laws of physics not to fall, the scene still felt imbued with a palpable sense of comfort. . . .

“We all experience pain and loss, and often we become inaudible,” she said a little later while accepting the award for Best Urban Contemporary Album. “My intention for the film and album was to create a body of work that would give a voice to our pain, our struggles, our darkness, and our history—to confront issues that make us uncomfortable. It’s important to me to show images to my children that reflect their beauty.” If that project of reflection found a prism in Lemonade, then tonight’s performance was its apex.

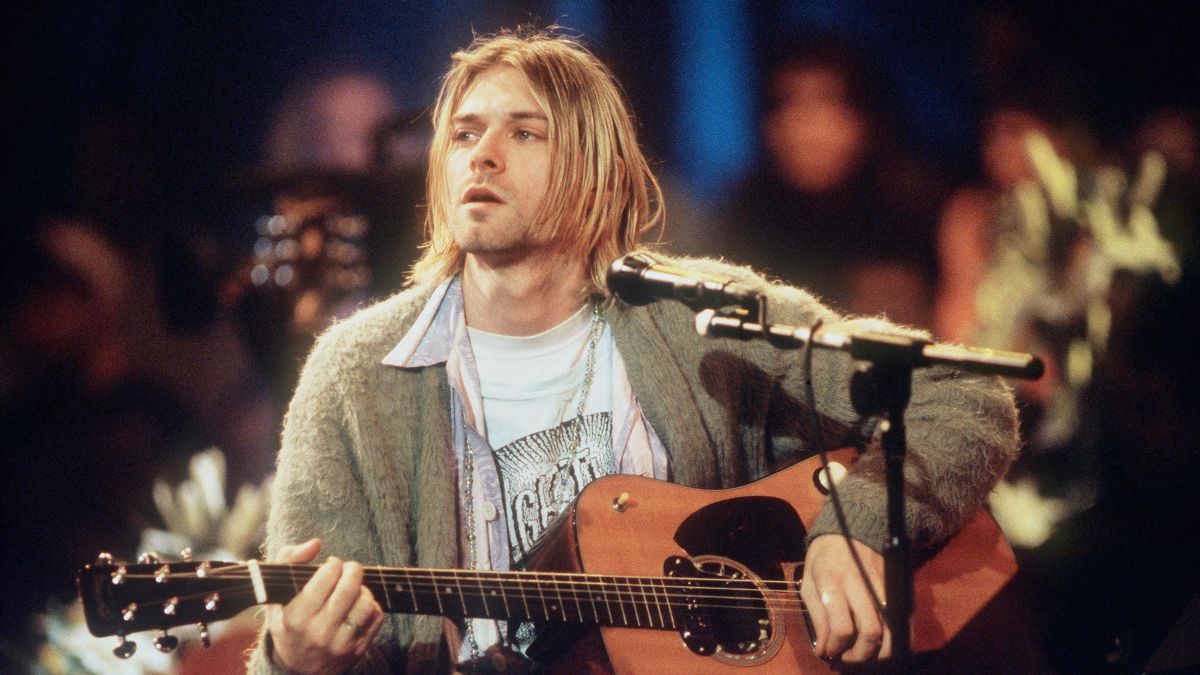

Profile Example #1: “Dave Grohl and the Foo Fighters” by Carl Wilkinson (Financial Times 8 August 2011)

A group of record company executives, sitting down to sketch the perfect rock star, may well come up with someone a little like Dave Grohl. He has the look—long, thick black hair; he has the talent—he plays the drums, guitar and piano, he sings and he writes his own songs; and, above all, he has both pedigree and credibility.

In the early 1990s, as drummer with seminal grunge band Nirvana, Grohl helped change the face of popular music. Today, as lead singer with stadium-filling rock giants Foo Fighters, he is a multi-millionaire who has sold more than 15 million albums worldwide, won six Grammy awards and is president of his own record label. Alongside Foo Fighters he has a number of side projects (including supergroup Them Crooked Vultures, with Led Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones); a documentary about his band shot by Oscar-winning director James Moll was released last month and his seventh album, Wasting Light, is out on Monday. Now 42, Grohl—and his brand of rock ‘n’ roll—has grown up, had kids and settled down.

How did a man who was just a drummer and who never intended to make money from music end up as one of the biggest and wealthiest rock stars of the decade, succeeding in the face of a record industry in crisis?

We meet at Studio 606, the 8,000 sq ft recording space he built in 2005 in the Northridge area of Los Angeles. Outside, the Californian spring sunshine throws stark shadows across a neighbourhood that estate agents would describe euphemistically as “mixed”; from inside this large utilitarian building, with its tinted windows, the blue sky looks almost overcast.

Grohl, who is tall, lean and has grown into his slightly goofy looks, sets down the keys to his decidedly un-rock ‘n’ roll grey BMW estate, tucks his shoulder-length hair behind his ear and flips the lid on his laptop. “Sorry,” he beams. “I’ve just got to check my e-mail. I want to see if my daughter got into private school.” Grohl married Jordyn Blum in 2003, and they have two daughters, Violet Maye, aged four, and Harper Willow, one.

The upstairs lounge looks like a bachelor pad: there’s a fridge, jukebox and widescreen TV with an eclectic selection of boxsets: The Office, ACDC and Bon Jovi gigs, and a tape of the Make-up and Effects trade show 1997. Scattered across the purple sofa are cushions covered with old band T-shirts (Slayer, The Police, Black Sabbath, Motorhead, Led Zeppelin) made by Grohl’s mother. “She called up and said ‘David, what do you want me to do with those T-shirts in the attic?’,” says Grohl in a falsetto.

Downstairs, a vast recording studio complete with Persian rugs and a grand piano in the corner leads on to a warehouse filled with carefully labelled guitar cases, drums and assorted equipment. Among the platinum records, framed posters and photographs hanging in the corridor outside the soundproofed control room where we adjourn to talk is the iconic cover of Nirvana’s 1991 album Nevermind, which celebrates its 20th anniversary in September.

Nevermind (and Nirvana) is both a gift and a curse to Grohl now. “For 16 years I’ve had to balance these two things: my love and respect of Nirvana and my love and respect of the Foo Fighters.” He lifts first his right hand then his left and balances the two, the large feathers tattooed on both forearms gently rising and falling. “I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for Nirvana, there’s no question. But I don’t know if I’d be alive if it wasn’t for the Foo Fighters. I try to keep them at a balance that is very respectful of each other.”

Despite Grohl’s desire to move on, the legacy of Nirvana’s groundbreaking album still haunts him, and for good reason. Nevermind changed popular culture. Until the release of that album in 1991, music was dominated by pop giants such as Madonna, Michael Jackson and Whitney Houston. The alternative music scene was just that: lo-fi, raw-sounding and based on a punk DIY ethos that came to be known as grunge.

“Grunge emerged from the Pacific north-west,” explains the writer Mark Yarm, whose book Everybody Loves Our Town: An Oral History of Grunge will be published in September to coincide with Nevermind’s anniversary. “It’s unclear who coined the term, but it came to mean guitar bands who had a certain unkempt style and usually came from Seattle. It was a movement that was always supposed to transcend the cash. Success was viewed very warily. People like Nirvana’s lead singer Kurt Cobain were resistant to success, yet very much sought it at the same time.”Grohl, who never imagined himself becoming a doctor, lawyer or writer, recorded his first album at 15 in a studio near his parents’ house in Springfield, Virginia—a suburb of Washington, DC. “The intention wasn’t to become U2, it was to satisfy that need to accomplish something outside of the mainstream system,” he says.

That early anti-commercial intent symbolised the ethos of the alternative music scene. In 1990, Grohl became the drummer for Seattle-based band Nirvana, which had been formed by singer Kurt Cobain and bass player Krist Novoselic in 1987. Nirvana had already released a debut album, Bleach (1989), and the three-piece—Cobain, Novoselic and Grohl—toured small venues in a tiny van. It was a love of music that fuelled them, not the desire to become rich, famous rock stars.

All that changed when they teamed up with producer Butch Vig on their second album Nevermind. Where Bleach was a bona fide indie album released on the tiny Seattle-based Sub Pop label to which the band signed for an initial $600 advance, Nevermind was released by Geffen, a label owned by the Universal Music Group that was also home to the band’s idols Sonic Youth.

“Sonic Youth’s major label debut came out in 1990 and sold about 200,000 copies, which was considered a huge number in indie-rock circles back then,” explains Yarm. “It was just inconceivable that another ‘weird’, underground band like Nirvana, who really looked up to Sonic Youth, could sell millions and millions of albums.” Yet Nevermind, which was expected to sell around 200,000 copies, exploded.

“Many people point to the week in January 1992 when Nirvana knocked Michael Jackson—the King of Pop—off the top of the American charts as the moment alternative music truly went mainstream,” says Yarm. To date, Nevermind has sold more than 26 million copies worldwide.

The album marked a sea-change in popular culture: it was the birth of a sound, a fashion and a lifestyle that was as big as punk or the swinging 60s before it. In the same year as Nevermind was released, Douglas Coupland published his famous novel Generation X and the theme tune for this new generation was Nirvana’s breakthrough single “Smells Like Teen Spirit”—a raw, angry rallying cry that touched a nerve around the world.

Yet, for Grohl—at least initially—little changed. “It was just as much a shock to us as it was to everybody else. I think we were the last ones to believe it. Our world wasn’t changing within all of that. We had a gold record and we were still touring in a van. And then it went platinum—we sold a million records—and we were still touring in a van; I was still sharing a room with Kurt when we had a platinum record. Even after we sold 10 million albums I was still living in a back room at my friend’s house with a futon and a lamp.” He does remember being sent his first credit card though. Never a big spender, he immediately rushed to his local Benihana, the chain of Japanese restaurants.

Thanks to Nirvana’s success, record companies descended on Seattle, snapping up any band they could find. “It was a feeding frenzy,” says Yarm. “One executive told me that all the flights from LA to Seattle were constantly booked. If one of those planes had gone down, it would have destroyed the music industry.”

After the stratospheric success of Nevermind, Nirvana released just one further studio album, 1993’s In Utero, and toured to breaking point. In 1994, lead singer Kurt Cobain, struggling with the pressure, was flown home to the US from Rome after taking an overdose during the European leg of the band’s tour. On April 8 1994, Cobain was found dead at the house in Seattle he shared with his wife Courtney Love and their daughter Frances Bean. He had taken a heroin overdose and shot himself. His suicide shook the music world to its core, made global headlines and, in the eyes of many devastated fans, established Cobain as a tragic-romantic figure in the mould of Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison or Jimi Hendrix. He was 27 years old.

In the months after Cobain’s death, Grohl couldn’t bring himself to play music. “After Nirvana ended in April 1994, I didn’t really do much that year,” explains Grohl. It wasn’t until October 1994 that he felt ready to go back into the studio. “I didn’t have a plan or any major career aspiration,” he says. “I just felt like I needed to do something.”

Over the course of five days, he recorded 13-14 of his songs in a small studio near his house, playing all the instruments and singing every song. Grohl distributed 100 copies of the recording to friends and music industry insiders and, reticent to step into the limelight so soon after Nirvana, he called the project Foo Fighters, the second world war term for an unidentified flying object, as it “sounded more like a band”. Those recordings, which cost Grohl around $5,000, became Foo Fighters’ self-titled debut album. Released in 1995, it established Grohl as one of the biggest rock musicians in the world.

It’s practically unheard of for a drummer to make it as a lead singer—perhaps the only other famous example is Phil Collins, who forged a solo career after his time in Genesis. Yet Collins is not playing stadium gigs 20 years on. When almost every other band of his generation has fallen by the wayside, what is it about Grohl and Foo Fighters that still resonates?

“Their music is no nonsense, blue-collar everyman music,” explains Butch Vig, who has produced the band’s new album Wasting Light. “I think that people feel like they know the band. They can relate to their songs, but they can also relate to them as individuals.” Today, after some personnel changes over the years, Foo Fighters consist of drummer Taylor Hawkins, guitarists Chris Shiflett and Pat Smear, bass player Nate Mendel and Grohl. They are a friendly, close-knit five-piece, who share jokes nonstop and banter about moments on tour. Over the course of 16 years and seven studio albums, the band has honed a particular brand of emotionally charged rock that has transcended their early grunge influences. Grohl writes melodies with the energy of punk rock that form an enviable greatest hits package guaranteed to fill any stadium in the world (in June 2008 the band played two consecutive shows at the 90,000-capacity Wembley Stadium).

The band’s new album is in some ways a return to the sound and approach of their early records. “There’s no question that history is a big part of this record,” admits Grohl. Despite his shiny, well-equipped studio, he decided to record Wasting Light in his garage at home, and in a nod to his lo-fi, DIY roots, recorded to tape rather than digitally on a computer. Like Nevermind, Wasting Light is something of an antidote to the overproduced mainstream pop that currently fills the charts. It’s not the only thing that sets the band apart.

The music industry has changed since Foo Fighters released their first album in 1995. “Historically record sales accounted for the majority of band revenues,” explains Chris Carey, senior economist at PRS for Music, a not-for-profit organisation which collects and distributes public performance royalties for composers, songwriters and music publishers. “As record sales have suffered in recent years the industry has looked to other areas for revenue. Synchronisations [music used in computer games and TV programmes] and merchandise sales have become increasingly important, and the boom in live music is well reported. It used to be that bands would tour at a loss to sell CDs. Nowadays music is often given away in order to generate buzz and promote live events.”

How does this seismic shift in the record industry affect a band such as the Foo Fighters? “They’ve got an established fan base and a good track record, they’re an act coming to the top of the market,” says Carey. “Their revenues won’t be representative of what a band coming into the market now would experience. That existing fan base, I’d imagine, will still buy physical albums and, I would expect, have a good amount of money to spend on concert tickets so what you can charge for a Foo Fighters gig is more than you could for a newer band. As a result their earning profile will be quite healthy: a good mix of live and recorded.”

Today, thanks to industry pressures, many popstars often have to take the money wherever they can get it, whether it’s corporate gigs, sponsorship deals or product placement in music videos. In the week I met Foo Fighters, the Libyan revolution was erupting and Beyoncé, Nelly Furtado and Usher had donated to charity their million-dollar fees earned playing for the Gaddafi family. “We’ve done corporate gigs to pay for touring,” says Foo Fighters drummer Taylor Hawkins, “but we’ve never played for the Gaddafis! There’s nothing wrong with getting paid to play music as long as it’s in the realms of whatever moral standards you have … “

Despite the shift in the music industry, Foo Fighters, with a secure fan base and stable income have been able to pick and choose what they do. “I think at this point we’ve exceeded any of the expectations we had for this band—musically or financially,” explains Grohl. “The most important thing is that we do what we do with the same integrity we had when we started 16 years ago. We’re not a financially ambitious band—we’re doing just fine. It comes down to how much do you really need?”

Nate Mendel, the band’s bassist and longest-serving member after Grohl himself, agrees: “All these ways you can exploit your band commercially, we’ve done a lot of it, but compared to a band similar to us, we’ve held back. We wanted to be in a band that didn’t have to do that. It’s only our generation that’s ever had a problem with it. Prior to and after 80s punk rock and the alternative music of the 90s nobody cared. It’s only our generation that was cautious about exploiting their music.”

“Punk-rock guilt,” laughs Hawkins. “I’m flying in this private jet and eating lobster thermidor—but I’m not giving a song to Honda!”

As internet piracy has taken its toll on the record industry, revenue from live gigs and merchandise has become ever more important. “If you’re not making money from records you have to make it somewhere else,” says Carey. “Merchandise was up more than 20 per cent in 2009 growing at a good rate and in 2008 live music was up about 13-14 per cent which is boom growth.”

Piracy and the decline in record sales won’t have hit the Foo Fighters as hard as many other newer bands—which may explain why Grohl, who is president of his own label, Roswell Records, is unconcerned about file sharing. When he was growing up Grohl and his friends would swap tapes of their favourite bands despite campaigns warning that “home taping is killing the record industry”. Today, the internet has really put a dent in the music business, Grohl acknowledges, but for him file sharing is simply an extension of those home-made mix-tapes. “To me, the most important thing is that people come and sing along when we pull into town on tour,” he says. “Sharing music is not a crime. It shouldn’t be. There should be a deeper meaning to making music than just selling downloads.”

Grohl’s experience with Nirvana has coloured the way he now runs Foo Fighters. “I learnt a lot of lessons from being in Nirvana. A lot of beautiful things and a lot of …” he pauses, “lessons of what not to do. I’m not a businessman, but when it comes to making music I’ve kind of figured out a way of doing it without anyone getting hurt.” He drums his fingers, performing a short paradiddle against the arm of the leather sofa.

After his death, Cobain’s estate passed to his wife, the singer Courtney Love, who in 1997, with Cobain’s bandmates, formed Nirvana LLC, a limited liability company to oversee their interests. The three have at times fought over Nirvana’s legacy, almost going to court in 2002 (a settlement was reached the day before proceedings were due to begin) and in 2009 scrapping over the use of Cobain’s likeness in computer game Guitar Hero 5. In April 2006, Love sold 25 per cent of her share in Nirvana’s catalogue to Primary Wave Music for a reported $50m.

When he formed Foo Fighters, Grohl set up Roswell Records as a holding company for the band’s entire music catalogue, which is then licensed to a record company for a six- to seven-year period at a time. “Unfortunately, a lot of musicians sign away their freedoms when they enter into these big business contracts. It’s an age-old story. It’s still happening. I don’t think there’s a place for that kind of outside control when it comes to being creative.”

Are you a control freak? I ask. “Absolutely. No question. I am a controlling freak. I’m not a control freak, I’m a controlling freak. This is our baby. When it comes to making music, we have our own process, we have our own crooked democracy …”

Democracy? Or is it a benign dictatorship? “Well, yeah. Show me a band of five people where there’s no leader … I just don’t think it could happen. At the end of the day, it’s my name at the bottom of the cheque.”

Foo Fighters are now embarking on another stadium-filling world tour. As Grohl, the perfect rock star, headed off, I couldn’t help thinking of the two fortune cookies I’d spotted earlier pinned to his fridge. “An interesting musical opportunity is in your near future,” read one. The other said simply: “Study and prepare yourself and one day, your day will come.”

Profile Example #2: “Show Dog” by Susan Orlean (The New Yorker 20 February 1995)

If I were a bitch, I’d be in love with Biff Truesdale. Biff is perfect. He’s friendly, good-looking, rich, famous, and in excellent physical condition. He almost never drools. He’s not afraid of commitment. He wants children — actually, he already has children and wants a lot more. He works hard and is a consummate professional, but he also knows how to have fun.

What Biff likes most is food and sex. This makes him sound boorish, which he is not — he’s just elemental. Food he likes even better than sex. His favorite things to eat are cookies, mints, and hotel soap, but he will eat just about anything. Richard Krieger, a friend of Biff’s who occasionally drives him to appointments, said not long ago, “When we’re driving on I-95, we’ll usually pull over at McDonald’s. Even if Biff is napping, he always wakes up when we’re getting close. I get him a few plain hamburgers with buns — no ketchup, no mustard, and no pickles. He loves hamburgers. I don’t get him his own French fries, but if I get myself fries, I always flip a few for him into the back.”

If you’re ever around Biff while you’re eating something he wants to taste — cold roast beef, a Wheatables cracker, chocolate, pasta, aspirin, whatever — he will stare at you across the pleated bridge of his nose and let his eyes sag and his lips tremble and allow a little bead of drool to percolate at the edge of his mouth until you feel so crummy that you give him some. This routine puts the people who know him in a quandary, because Biff has to watch his weight. Usually, he is as skinny as Kate Moss, but he can put on three pounds in an instant. The holidays can be tough. He takes time off at Christmas and spends it at home, in Attleboro, Massachusetts, where there’s a lot of food around and no pressure and no schedule and it’s easy to eat all day. The extra weight goes to his neck. Luckily, Biff likes working out. He runs for fifteen or twenty minutes twice a day, either outside or on his Jog-Master. When he’s feeling heavy, he runs longer, and skips snacks, until he’s back down to his ideal weight of seventy-five pounds.

Biff is a boxer. He is a show dog — he performs under the name Champion Hi-Tech’s Arbitrage — and so looking good is not mere vanity; it’s business. A show dog’s career is short, and judges are unforgiving. Each breed is judged by an explicit standard for appearance and temperament, and then there’s the incalculable element of charisma in the ring. When a show dog is fat or lazy or sullen, he doesn’t win; when he doesn’t win, he doesn’t enjoy ancillary benefits of being a winner, like appearances as the celebrity spokesmodel on packages of Pedigree Mealtime with Lamb and Rice, which Biff will be doing soon, or picking the best-looking bitches and charging them six hundred dollars or so for his sexual favors, which Biff does three or four times a month. Another ancillary benefit of being a winner is that almost every single weekend of the year, as he travels to shows around the country, he gets to hear people applaud for him and yell his name and tell him what a good boy he is, which is something he seems to enjoy at least as much as eating a bar of soap.

Pretty soon, Biff won’t have to be so vigilant about his diet. After he appears at the Westminster Kennel Club’s show, this week, he will retire from active show life and work full time as a stud. It’s a good moment for him to retire. Last year, he won more shows than any other boxer, and also more than any other dog in the purebred category known as Working Dogs, which also includes Akitas, Alaskan malamutes, Bernese mountain dogs, bull-mastiffs, Doberman pinschers, giant schnauzers, Great Danes, Great Pyrenees, komondors, kuvaszok, mastiffs, Newfoundlands, Portuguese water dogs, Rottweilers, St. Bernards, Samoyeds, Siberian huskies, and standard schnauzers. Boxers were named for their habit of standing on their hind legs and punching with their front paws when they fight. They were originally bred to be chaperons — to look forbidding while being pleasant to spend time with. Except for show dogs like Biff, most boxers lead a life of relative leisure. Last year at Westminster, Biff was named Best Boxer and Best Working Dog, and he was a serious contender for Best in Show, the highest honor any show dog can hope for. He is a contender to win his breed and group again this year, and is a serious contender once again for Best in Show, although the odds are against him, because this year’s judge is known as a poodle person.

Biff is four years old. He’s in his prime. He could stay on the circuit for a few more years, but by stepping aside now he is making room for his sons Trent and Rex, who are just getting into the business, and he’s leaving while he’s still on top. He’ll also spend less time in airplanes, which is the one part of show life he doesn’t like, and more time with his owners, William and Tina Truesdale, who might be persuaded to waive his snacking rules.

Biff has a short, tight coat of fox-colored fur, white feet and ankles, and a patch of white on his chest roughly the shape of Maine. His muscles are plainly sketched under his skin, but he isn’t bulgy. His face is turned up and pushed in, and has a dark mask, spongy lips, a wishbone-shaped white blaze, and the earnest and slightly careworn expression of a small-town mayor. Someone once told me that he thought Biff looked a little bit like President Clinton. Biff’s face is his fortune. There are plenty of people who like boxers with bigger bones and a stockier body and taller shoulders — boxers who look less like marathon runners and more like weight-lifters — but almost everyone agrees that Biff has a nearly perfect head.

“Biff’s head is his father’s,” William Truesdale, a veterinarian, explained to me one day. We were in the Truesdales’ living room in Attleboro, which overlooks acres of hilly fenced-in fields. Their house is a big, sunny ranch with stylish pastel kitchen and boxerabilia on every wall. The Truesdales don’t have children, but at any given moment they share their quarters with at least a half-dozen dogs. If you watch a lot of dog-food commercials, you may have seen William — he’s the young, handsome, dark-haired veterinarian declaring his enthusiasm for Pedigree Mealtime while his boxers gallop around.

“Biff has a masculine but elegant head,” William went on. “It’s not too wet around the muzzle. It’s just about ideal. Of course, his forte is right here.” He pointed to Biff’s withers, and explained that Biff’s shoulder-humerus articulation was optimally angled, and bracketed his superb brisket and forelegs, or something like that. While William was talking, Biff climbed onto the couch and sat on top of Brian, his companion, who was hiding under a pillow. Brian is an English toy Prince Charles spaniel who is about the size of a teakettle and has the composure of a hummingbird. As a young competitor, he once bit a judge — a mistake Tina Truesdale says he made because at the time he had been going through a little mind problem about being touched. Brian, whose show name is Champion Cragmor’s Hi-Tech Man, will soon go back on the circuit, but now he mostly serves as Biff’s regular escort. When Biff sat on him, he started to quiver. Biff batted him with his front leg. Brian gave him an adoring look.

“Biff’s body is from his mother,” Tina was saying. “She had a lot of substance.”

“She was even a little extreme for a bitch,” William said. “She was rather buxom. I would call her zaftig.”

“Biff’s father needed that, though,” Tina said. “His name was Tailo, and he was fabulous. Tailo had a very beautiful head, but he was a bit fine, I think. A bit slender.”

“Even a little feminine,” William said, with feeling. “Actually, he would have been a really awesome bitch.”

The first time I met Biff, he sniffed by pants, stood up on his hind legs and stared into my face, and then trotted off to the kitchen, where someone was cooking macaroni. We were in Westbury, Long Island, where Biff lives with Kimberly Pastella, a twenty-nine-year-old professional handler, when he’s working. Last year, Kim and Biff went to at least one show every weekend. If they drove, they took Kim’s van. If they flew, she went coach and he went cargo. They always shared a hotel room.

While Kim was telling me all this, I could hear Biff rummaging around in the kitchen. “Biffers!” Kim called out. Biff jogged back into the room with a phony look of surprise on his face. His tail was ticking back and forth. It is cropped so that it is about the size and shape of a half-smoked stogie. Kim said that there was a bitch downstairs who had been sent from Pennsylvania to be bred to one of Kim’s other clients, and that Biff could smell her and was a little out of sorts. “Let’s go,” she said to him. “Biff, let’s go jog.” We went into the garage where a treadmill was set up with Biff’s collar suspended from a metal arm. Biff hopped on and held his head out so that Kim could buckle his collar. As soon as she leaned toward the power switch, he started to jog. His nails clicked a light tattoo on the rubber belt.

Except for a son of his named Biffle, Biff gets along with everybody. Matt Stander, one of the founders of Dog News, said recently, “Biff is just very very personable. He has a je ne sais quoi that’s really special. He gives of himself all the time.” One afternoon, the Truesdales were telling me about the psychology that went into making Biff who he is. “Boxers are real communicators,” William was saying. “We had to really take that into consideration in his upbringing. He seems tough, but there’s a fragile ego inside there. The profound reaction wand hurt when you would raise your voice at him was really something.”

“I made him,” Tina said. “I made Biff who he is. He had an overbearing personality when he was small, but I consider that a prerequisite for a great performer. He had such an attitude! He was like this miniature man!” She shimmied her shoulders back and forth and thrust out her chin. She is a dainty, chic woman with wide-set eyes and the neck of a ballerina. She grew up on a farm in Costa Rica, where dogs were considered just another form of livestock. In 1987, William got her a Rottweiler for a watchdog, and a boxer, because he had always loved boxers, and Tina decided to dabble with them in shows. Now she makes a monogrammed Christmas stocking for each animal in their house, and she watches the tape of Biff winning at Westminster approximately once a week. “Right from the beginning, I made Biff think he was the most fabulous dog in the world,” Tina said.

“He doesn’t take after me very much,” William said. “I’m more of a golden retriever.”

“Oh, he has my nature,” Tina said. “I’m very strong-willed. I’m brassy. And Biff is an egotistical, self-centered, selfish person. He thinks he’s very important and special, and he doesn’t like to share.”

Biff is priceless. If you beg the Truesdales to name a figure, they might say that Biff is worth around a hundred thousand dollars, but they will also point out that a Japanese dog fancier recently handed Tina a blank check for Biff. (She immediately threw it away.) That check notwithstanding, campaigning a show dog is a money-losing proposition for the owner. A good handler gets three or four hundred dollars a day, plus travel expenses, to show a dog, and any dog aiming for the top will have to be on the road at least a hundred days a year. A dog photographer charges hundreds of dollars for a portrait, and a portrait is something that every serious owner commissions, and then runs a full-page ad in several dog-show magazines. Advertising a show dog is standard procedure if you want your dog or your presence on the show circuit to get well known. There are also such ongoing show-dog expenses as entry fees, hair-care products, food, health care, and toys. Biff’s stud fee is six hundred dollars. Now that he will not be at shows, he can be bred several times a month. Breeding him would have been a good way for him to make money in the past, except that whenever the Truesdales were enthusiastic about a mating they bartered Biff’s service for the pick of the litter. As a result, they now have more Biff puppies than Biff earnings. “We’re doing this for posterity,” Tina says. “We’re doing it for the good of all boxers. You simply can’t think about the cost.”

On a recent Sunday, I went to watch Biff work at one of the last shows he would attend before his retirement. The show was sponsored by the Lehigh Valley Kennel Club and was held in a big, windy field house on the campus of Lehigh University, in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. The parking lot was filled with motor homes pasted with life-size decals of dogs. On my way to the field house, I passed someone walking an Afgan hound wearing a snood, and someone else wiping down a Saluki with a Flintstones beach towel. Biff was napping in his crate — a fancy-looking brass box with bright silver hardware and with luggage tags from Delta, USAir, and Continental hanging on the door. Dogs in crates can look woeful, but Biff actually likes spending time in his. When he was growing up, the Truesdales decided they would never reprimand him, because of his delicate ego. Whenever he got rambunctious, Tina wouldn’t scold him — she would just invite him to sit in his crate and have a time-out.

On this particular day, Biff was in the crate with a bowl of water and a gourmet Oinkeroll. The boxer judging was already over. There had been thirty-three in competition, and Biff had won Best in Breed. Now he had to wait for several hours while the rest of the working breeds had their competitions. Later, the breed winners would square off for Best in Working Group. Then, around dinnertime, the winners of the other groups — sporting dogs, hounds, terriers, toys, non-sporting dogs, and herding dogs — would compete for Best in Show. Biff was stretched out in the crate with his head resting on his forelegs, so that his lips draped over his ankle like a café curtain. He looked bored. Next to his crate, several wire-haired fox terriers were standing on tables getting their faces shampooed, and beyond them a Chihuahua in a pink crate was gnawing on its door latch. Two men in white shirts and dark pants walked by eating hot dogs. One of them was gesturing and exclaiming, “I thought I had great dachshunds!”

Biff sighed and closed his eyes.

While he was napping, I pawed through his suitcase. In it was some dog food; towels; an electric nail grinder; a whisker trimmer; a wool jacket in a lively pattern that looked sort of Southwestern; an apron; some antibiotics; baby oil; coconut-oil coat polish; boxer chalk powder; a copy of Dog News; an issue of ShowSight magazine, featuring an article subtitled “Frozen Semen — Boon or Bain?” and a two-page ad for Biff, with a full-page, full-color photograph of him and Kim posed in front of a human-sized toy solider; a spray bottle of fur cleanser; another Oinkeroll; a rope ball; and something called a Booda Bone. The apron was for Kim. The baby oil was to make Biff’s nose and feet glossy when he went into the ring. Boxer chalk powder — as distinct from, say, West Highland-white-terrier chalk powder — is formulated to cling to short, sleek boxer hair and whiten boxers’ white markings. Unlike some of the other dogs, Biff did not need to travel with a blow dryer, curlers, nail polish, or detangling combs, but, unlike some less sought-after dogs, he did need a schedule. He was registered for a show in Chicago the next day, and had an appointment at a clinic in Connecticut the next week to make a semen deposit, which has been ordered by a breeder in Australia. Also, he had a date that same week with a bitch named Diana who was about to go into heat. Biff has to book is stud work after shows, so that it doesn’t interfere with his performance. Tina Truesdale told me that this was typical of all athletes, but everyone who knows Biff is quick to comment on how professional he is as a stud. Richard Krieger, who was going to be driving Biff to his appointment at the clinic in Connecticut, once told me that some studs want to goof around and take forever but Biff is very businesslike. “Bing, bang, boom,” Krieger said. “He’s in, he’s out.”

“No wasting of time,” said Nancy Krieger, Richard’s wife. “Bing, bang, boom. He gets the job done.”

After a while, Kim showed up and asked Biff if he needed to go outside. Then a handler who is a friend of Kim’s came by. He was wearing a black-and-white houndstooth suit and was brandishing a comb and a can of hair spray. While they were talking, I leafed through the show catalogue and read some of the dogs’ names to Biff, just for fun — names like Aleph Godol’s Umbra Von Carousel and Champion Spanktown Little Lu Lu and Ranchlake’s Energizer O’Motown and Champion Beaverbrook Buster V Broadhead. Biff decided that he did want to go out, so Kim opened the crate. He stepped out and stretched and yawned like a cat, and then he suddenly stood up and punched me in the chest. And announcement calling for all toys to report to their ring came over the loudspeaker. Kim’s friend waved the can of hair spray in the direction of a little white poodle shivering on a table a few yards away and exclaimed, “Oh, no! I lost track of time! I have to go! I have to spray up my miniature!”

Typically, dog contestants first circle the ring together; then each contestant poses individually for the judge, trying to look perfect as the judge lifts its lips for a dental exam, rocks its hindquarters, and strokes its back and thighs. The judge at Lehigh was a chesty, mustached man with watery eyes and a grave expression. He directed the group with hand signals that made him appear to be roping cattle. The Rottweiler looked good, and so did the giant schnauzer. I started to worry. Biff had a distracted look on his face, as if he’d forgotten something back at the house. Finally, it was his turn. He pranced to the center of the ring. The judge stroked him and then waved his hand in a circle and stepped out of the way. Several people near me began clapping. A flashbulb flared. Biff held his position for a moment, and then he and Kim bounded across the ring, his feet moving so fast that they blurred into an oily sparkle, even though he really didn’t have very far to go. He got a cookie when he finished the performance, and other a few minutes later, when the judge wagged his finger at him, indicating that Biff had won again.

You can’t help wondering whether Biff will experience the depressing letdown that retired competitors face. At least, he has a lot of stud work to look forward to, although William Truesdale complained to me once that the Truesdales’ standards for a mate are so high — they require a clean bill of health and a substantial pedigree — that “there just aren’t that many right bitches out there.” Nonetheless, he and Tina are optimistic that Biff will find enough suitable mates to become one of the most influential boxer sires of all time. “We’d like to be remembered as the boxer people of the nineties,” Tina said. “Anyway, we can’t wait to have him home.”

“We’re starting to campaign Biff’s son Rex,” William said. “He’s been living in Mexico, and he’s a Mexican champion, and now he’s ready to take on the American shows. He’s very promising. He has a fabulous rear.”

Just then, Biff, who had been on the couch, jumped down and began pacing. “Going somewhere, honey?” Tina asked.

He wanted to go out, so Tina opened the back door, and Biff ran into the back yard. After a few minutes, he noticed a ball on the lawn. The ball was slippery and a little too big to fit in his mouth, but he kept scrambling and trying to grab it. In the meantime, the Truesdales and I sat, stayed for a moment, fetched ourselves turkey sandwiches, and then curled up on the couch. Half an hour passed, and Biff was still happily pursuing the ball. He probably has a very short memory, but he acted as if it were the most fun he’s ever had.

Profile Example #3: “A Vampire’s Life? It’s Really Draining” by Monica Hesse (The Washington Post 24 November 2008)

The vampire drank cola at the movie because the vampire does not drink blood. She remarked that the giggling teenagers buying popcorn in their capes were “really, really great,” but the vampire herself wore jeans and a gray T-shirt, as she breaks out vamparaphernalia only for special occasions. And after the 9:15 showing of the new hit film “Twilight,” the vampire went straight home with her teenage son, because the vampire is a doting mom.

The vampire is Linda Rabinowitz, also known as Selket. She’s in her thirties, lives in central Virginia and radiates warm approachability. If you needed a quarter to get on the bus, she is the stranger you would ask.

If you maintained eye contact for too long, though, she might be tempted to quietly sip away at your energy, or prana, leaving you a little fatigued, because that is what empathic and psychic vampires feed on, and that is what Rabinowitz says she is. But she would never actually do that, because “good” vampires — both psychic and blood-consuming sanguinarians — operate under the Black Veil, a strict code of ethics that stipulates feeding only off willing donors.

What did you expect, some kind of monster?

Every time Hollywood comes out with an undead movie — pale skin, exposed throats, eternal lust — everyone wants to talk to real vampires. “Twilight” — which made $70.6 million over the weekend and recounts the love story of human teen Bella and vampire teen Edward — is no exception. (Hey! Tyra just had one on her show — some woman called Vampyra who lights her son on fire and says he likes the rush!)

Vampyra is exactly what the vampire community does not need right now.

Because frankly, they are sooo over the negative exposure. Over explaining that many of them really like sunlight, over teaching that vampires are born and not made, over answering such questions as: Do you really sleep in coffins and never die? Please, people. Please.

Vampires, depressingly, are Just Like Us.

* * *

“I really look at my condition as more of an energy deficiency,” says one 27-year-old Washingtonian, whose condition, she says, is vampirism. She goes by Scarlet in the vampire community, but she — like many vampires — does not allow her real name to be printed because she has not come out of the coffin in real life. “I don’t always produce enough energy to sustain myself,” Scarlet says. She noticed this deficiency while a child, she says, and “awakened” as a vampire in her teens.

So the woman, who recently relocated from the South, occasionally needs to take a little energy from her boyfriend. Just a teaspoon of blood, once every week or 10 days, and always collected with disposable single-use lancet. Safety first, safety first. Feeding is “not as parasitic as people think,” she says. “It’s more of a reciprocal thing.” While she has an energy deficiency, she says, her boyfriend has an energy surplus. “He’d been a little hyperactive, and now he can actually sleep through the night.” It’s almost medicinal, really.

Rabinowitz is just as discriminating when it comes to empathic feeding. “I stay away from people with medical issues,” she says. “There’s just too much complex emotion there.” Also, no drunks, no druggies, no head cases, and “I try to stay away from people who are evil, basically.” Although she most often feeds from one willing donor (most often, her long-term partner), she is able to take in ambient energy from crowds, without people even realizing. Places such as Hard Times Cafe and Applebee’s can be good spots, she says, because of the generally positive energy.

Think of this next time you’re noshing on Nachos Nuevos.

At this point, it seems wise to address the fact that we are giving serious discussion to vampires. Or, at least, people who genuinely believe they are vampires. Because vampires are something that we’ve been taught are not, er, real. And if they are, shouldn’t they be slinking around a Transylvanian forest wearing a cravat?

The vampires expect this reaction, and they are prepared for it.

“We’re taking advantage of the release of ‘Twilight’ ” to try to get some truths out, says Michelle Belanger, a prominent psychic vampire and author of “The Psychic Vampire Codex.” For example, did you know that New York has at least 1,000 self-identified vampires? “If we take that as a sample,” Belanger says, “it’s less than 1 percent, but we’d still have tens of thousands worldwide.”

Repeat: Tens of thousands of people believe they are vampires. It is hard, however, to verify this, seeing as it’s a self-selecting title, and each vampire might have a different definition of what it means to be vampirical. Some are more “Anne Rice,” some are more “Aren’t you my yoga instructor?”

* * *

Down in Georgia, the Atlanta Vampire Alliance and its research arm, Suscitatio Enterprises LLC, have been working for two years to collect useful data on the community. More than 700 vampires have answered hundreds of survey questions, and from the study we learn that vampires:

1. Have much higher rates of asthma, migraines and anemia than normal humans.

2. Most commonly live in California, followed by Georgia, Texas, New York and Ohio. (The District does not have a high concentration — House Eclipse was the most prominent vampire group in the area, but its Web site does not appear to be updated regularly.

3. Are an average age of 28.

Also, only 17 percent of vampires drink blood; 31 percent are solely psychic, and the rest are hybrids.

The keeper of this data is J. Collins, who is also the administrator for Voices of the Vampire Community, which Collins describes as “kind of like the United Nations of Vampires,” except that it exists purely to dis-perse information and does not govern.

On Friday afternoon, Collins, who goes by the vampire name Merticus, was fielding media requests for interviews with vampires. He casually rattled off the schedule of just about every major vampire in the United States. Father Sebastiaan was in New York, briefly, before heading off to Paris. Don Henrie, a “lifestyler” who really does sleep in a coffin, just taped Maury Povich and was heading back to Las Vegas with his manager. Belanger was giving a lecture on vampires at a college in Florida.

“We really hope that the fruits of what we’re doing now will lead to us being understood later,” he said. The VVC exists to help vampires form a cohesive community, present a united front.

Of course, as with any community, there have been internal struggles:

Psychic vampires have perceived sanguinarians as rudimentary brutes, while blood vampires “had a very hard time accepting that psychic vampires are legitimate,” Belanger says. She sighs. “It boiled down to: Oh, sure, ‘I’m taking your energy, I’m taking your energy.’ [Sanguinarians] have a hard time wrapping their brains around the psychic stuff.”

Anyway. That hatchet was mostly buried a few years ago, Belanger says, especially after Sanguinarius, a respected blood-drinking vampire (and founder of the resource site http://Sanguinarius.org), changed an ear-lier antagonistic position and came out in support of unity.

In a phone interview, Sanguinarius, whose real name is Elizabeth, wholeheartedly expresses solidarity, but goes on to say that psychic vampires “concern themselves as much as we do with ethics . . . but all ethics aside, they could just walk into some place, and pick some person, and feed on them until the person flops down and twitches. The cops can’t do anything because it’s not illegal. Now if I did that . . .”

You can understand the frustration.

You can also understand the inter-community annoyance, which sounds pretty much like run-of-the-mill interoffice tension (Oh, sure, she has kids, so she gets to leave at 5. Now if I tried that . . .).

It’s all so borrring, so very borrring. Deep down, deep way down, we don’t really want vampires to be just like us, because we are pretty lame. Deep down, we know that if we really have nothing to fear, then we also have nothing to be titillated by, nothing to make us shriek, then laugh, then shriek again. No, no, don’t suck my blood! Or do. Okay, do.

It’s doubly depressing to learn that some academics are viewing vampires as less mythical creature, more identity group. It’s the next step in society’s evolution, says Joe Laycock, author of the forthcoming “Vampires Today: The Truth About Modern Vampires.” See, “in the Middle Ages people didn’t really consider themselves as individuals,” Laycock explains. “These modern ‘Who am I?’ questions are very new. Self-identified vampires take it to the next logical progression: Maybe I can’t take for granted that I’m human. Maybe who I am is not a person at all.”

In the future, we will all be vampires.

In “Twilight,” the sensitive vampire Edward can scale trees in seconds, can stop moving cars with an outstretched hand, can read people’s minds, and gets all glittery when he stands in the sunlight.

When Rabinowitz is asked whether she possesses any of these skills — any at all — she thinks about it for a second. “I do have a heightened sense of smell” when she feeds, she says. And, of course, she can read people’s energy, which is not exactly like reading people’s minds, but it’s something.

The energy in the movie theater, for example, was really happy. A lot of people overcome with excitement and emotion. Personally, she loved the movie. Unlike previous vampire movies, she thought this one went a long way toward showing that vampires are complex, multifaceted beings. Regular folk.

Vampires should be pleased.

We average humans are a little disappointed.

Profile Example #4: “Nathan Wolfe: Virus Hunter” (MLA Style)

Profile Example #5: “John Green, Author Extraordinaire” (MLA Style)

A concise, biographical sketch of a subject (usually a person representing an issue).

A discovery tool that helps you ask insightful questions or follow a specific pattern of thinking.

Sources that require an Internet connection and/or electronic device (computer, DVD player, radio, television, etc.) to access. For example: websites, podcasts, videos, movies, television shows, audio recordings.

Sources that were originally intended to be accessed and read in physical, printed form. For example: books, newspapers, magazines, journals, newsletters, other periodicals or publications.

Source material that was collected by the researcher and analyzed for research purposes. For example: Personal experiences, field observations, interviews, surveys, case studies, experiments.

A category of artistic composition, as in music or literature, characterized by similarities in form, style, or subject matter.

The broad idea or issue that a message deals with.

The goal or objective that the creator of a message is trying to achieve by communicating that message.

The groups of people (demographics) who receive a message.

The circumstances that form the setting for an event, statement, or idea, and in terms of which it can be fully understood and assessed.

A beginning section which states the purpose and goals of the following writing, generally followed by the body and conclusion. The introduction typically describes the scope of the document and gives the brief explanation or summary of the document.

The main idea, point, or claim of a written work. Plural: theses.

The majority of an essay in which claims are presented and subsequently proven, described, analyzed, or explained.

A short, personal story about the writer's own experiences.

A conversation between two or more characters, noted with quotation marks.

A group of words taken from a text or speech and repeated by someone other than the original author or speaker, noted with quotation marks.

The last paragraph in an academic essay that generally summarizes the essay, presents the main idea of the essay, or gives an overall solution to a problem or argument given in the essay.

The manner of expressing thought in language characteristic of an individual, period, school, or nation.

The general feeling or attitude of a piece of writing.

The written equivalent of a snapshot, which attempts to reveal a person’s inner nature.

The person, group of people, place, or animal that is the focus of a profile.

A situation or detail of a character that complicates the main thread of a plot and presents a challenge, choice, or conflict.