26

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Invent the content of your literary analysis with critical reading strategies. (GEO 1, 4; SLO 4)

- Organize your literary analysis to highlight your interpretation of the text. (GEO 2; SLO 1, 2)

- Use an appropriate voice and quotations to lend authority to your analysis. (GEO 1, 2; SLO 5)

- Create an appropriate design by following formatting requirements and adding visuals. (GEO 2; SLO 3)

A literary analysis poses an interpretive question about a literary text and then uses that question to explore an intriguing aspect of the text, its characters, its author, or the historical context in which the work was written. In a literary analysis, your purpose is to think critically about the text and offer readers new and interesting insights into what the work means or what it represents. A literary analysis interprets the text, analyzes its structure and features, and examines it through the lenses of historical, cultural, social, biographical, or other contexts. An effective literary analysis helps readers understand what makes a literary work thought-provoking, revealing, troubling, or enjoyable. These kinds of analyses also contribute to the larger scholarly conversation about the meaning and purpose of literature.

When writing a literary analysis, you shouldn’t feel like you need to prove that you have the “right” interpretation. Instead, your literary analysis should invite your readers to consider the work from new and interesting angles, while showing them how a particular perspective can lead to fresh insights. Usually, you will write literary analyses for courses that feature creative works, such as English, language studies, cultural studies, gender studies, and history. Some college courses, in the sciences, human sciences, and technology, incorporate literature to help students better understand the ethical situations and cultures in which important historical or cultural shifts occurred.

Student Example: “. . . Happily Ever After” or What Fairytales Teach Girls About Being Women by Alice Neikirk

Inventing Your Literary Analysis’s Content

The first challenge in writing a literary analysis is coming up with an interesting interpretive question about the work. As you read and research the text, look for evidence that might lead to insights that go beyond the obvious.

Authors want their literary works to affect readers in specific ways. Authors rarely present straightforward, simple lessons, but they do want to influence the way readers view the world. As you are exploring the text from different angles, try to figure out what message or theme the author is trying to convey.

Read, Reread, Explore

If the literary work is a short story or novel, read it at least twice. If it is a poem, read it again and again, silently and aloud, to get a sense of how the language works and how the poem makes you feel. As you read the text, mark or underline anything that intrigues or puzzles you. Write observations and questions in the margins.

Inquiring: What’s Interesting Here?

As you are reading and exploring the text, try to come up with a few thought-provoking questions that focus on the work’s genre, plot, characters, or use of language. The goal is to develop your interpretive question, which will serve as your angle for seeing the text from a new point of view.

Explore the genre.

In your literature classes, your professors will use the term genre somewhat differently than it is used in this book. Literary works fall into four major genres: fiction, poetry, drama, and literary nonfiction. Each of these genres can be further divided into subgenres.

- Fiction: short stories, novellas, novels, comics, science fiction, romance, mysteries, horror, fantasy, historical fiction

- Poetry: sonnets, ballads, haikus, villanelles, odes, sestinas, open verse

- Drama: plays, screenwriting, comedies, tragedies, musicals, operas

- Literary nonfiction: memoirs, autobiographies, profiles, biographies, essays, nature writing, sports writing, religion, politics

- Folklore: mythology, epics, folk tales, legends, fairy tales

While examining the text, ask yourself why the author chose this genre or sub-genre of literature and not another one. Why a poem rather than a story? Why a short story rather than a novel? Also, look for places where the author follows the genre or strays from it. How does the genre constrain what the author can do? How does she or he bend the genre to fit the story that he or she wants to tell? How does the author use this genre in a unique or interesting way?

Explore the complication or conflict.

In almost every literary work, a key complication or conflict is at the center of the story. What are the complications or conflicts that arise from the narrative? How do the characters react to the complications? And how are these complications and conflicts resolved? Keep in mind that conflicts often arise from characters’ values and beliefs or situations in which characters find themselves. What choices do the characters make, how do those choices reflect their values and beliefs, and what are the results of those choices? Are there conflicts between characters, between characters and their surroundings, between characters’ aspirations, or between competing values and beliefs?

Explore the plot.

Plot refers not just to the sequence of events but also to how the events arise from the main conflict in the story. How do the events in the story unfold? Why do the events arise as they do? Which events are surprising or puzzling? Where does the plot seem to stray from a straight path? When studying the plot, pay special attention to the climax, which is the critical moment in the story. What happens at that key moment, and why is this moment so crucial? How do the characters react to try to resolve the conflict, for better or worse?

Explore the characters.

The characters are the people who inhabit the story or poem. Who are they? What kinds of people are they? Why do they act as they do? What are their values, beliefs, and desires? How do they interact with each other, or with their environment and setting? You might explore the psychology or motives of the characters, trying to figure out the meaning behind their decisions and actions.

Explore the setting.

When and where does the story take place? What is the broader setting—culture, social sphere, historic period? Also, what is the narrow setting—the details about the particular time and place? How does the setting con-strain the characters by influencing their beliefs, values, and choices? How does the setting become a symbol that colors the way readers interpret the work? Is the setting realistic, fantastical, ironic, or magical?

Explore the language and tone.

How does the author’s tone or diction color your attitude toward the characters, setting, or theme? What feeling or mood does the work’s tone evoke, and how does that tone evolve as the story or poem moves forward?

Explore the use of tropes.

Also, pay attention to the author’s use of metaphors, similes, and analogies. How does the author use these devices to deepen the meaning of the text or bring new ideas to light? What images are used to describe the characters, events, objects, or setting? Do those images become metaphors or symbols that color the way readers understand the work, or the way the characters see their world?

Researching: What Background Do You Need?

While most literary analyses focus primarily on the literary text itself, you can also research the historical background of a work and its author. Internet and print sources are good places to find relevant facts, information, and perspectives that will broaden your understanding.

Research the author.

Learning about the author can often lead to interpretive insights. The author’s life experiences may help you understand his or her intentions. You might also study the events that were happening in the author’s time because the work itself might directly or indirectly respond to them.

Research the historical setting.

You could also do research about the text’s historical setting. If the story takes place in a real setting, you can read about the historical, cultural, social, and political forces that were in play at that time and in that place.

Research the science.

Human and physical sciences can often give you insights into human behavior, social interactions, or natural phenomena. Sometimes interesting insights into characters and events.

Organizing and Drafting Your Literary Analysis

So far, you have read the literary work carefully, taken notes, done some research, and perhaps written one or more responses. Now, how should you begin drafting your literary analysis? Here are some ideas for getting your ideas onto the page or the screen.

The Introduction: Establish Your Interpretive Question

Introductions in literary analyses usually contain a few common features:

Include background information that leads to your interpretive question.

Draw your reader into your analysis by starting with an intriguing feature of the work. You can use a quote from the work or the author, state a historical fact that highlights something important, or draw attention to a unique aspect of the work or the author.

State your interpretive question prominently and clearly.

Make sure your reader understands the question that your analysis will investigate. If necessary, make it obvious by saying something like, “This analysis will explore why. . . .” That way, your readers will clearly understand your purpose.

Place your thesis statement at or near the end of the introduction.

Provide a clear thesis that answers your interpretive question. Since a literary analysis is academic in nature, your readers will expect you to state your main point or thesis statement somewhere near the end of the introduction. Here are examples of a weak thesis statement and a stronger one:

Examples

Weak: Jane Austen’s Emma is a classic early nineteenth-century novel that has stood the test of time.

Stronger: Jane Austen’s Emma is especially meaningful now, because Emma herself is a complex female character whose passion for matchmaking resonates with today’s socially networked women.

The Body: Summarize, Interpret, Support

In the body paragraphs, take your readers through your analysis point by point, showing them why your interpretation makes sense and leads to interesting new insights.

Summarize and describe key aspects of the work.

You can assume that your readers will be familiar with the literary work, so you don’t need to provide a complete summary or fully explain who the characters are. But you should describe the aspects that demand special attention. You may wish to focus on a particular scene, or on certain features, such as a character, interactions between characters, setting, language, symbols, plot features, and so forth. Discuss only those aspects of the work that lay the foundation for your analysis.

Build your case, step by step.

Keep in mind that the goal of a literary analysis is not to prove that your interpretation is correct but to show that it is plausible and leads to interesting insights into the text. Take your readers through your analysis point by point. Back up each key point with reasoning and evidence and make connections to your interpretive question and thesis statement.

Cite and quote the text to back up and illustrate your points.

The evidence for your interpretation should come mostly from the text itself. Show your readers what the text says by quoting and citing it, or by describing and citing key scenes and events.

Include outside support, where appropriate.

Other scholars have prob-ably offered their own critical remarks on the text. You can use their analyses to support your own interpretations, or you can work against them by arguing for a different or new perspective. Make sure you cite these sources properly. Do not use their ideas and phrasings without giving them credit or quoting them. (Your professor, who is an expert in these literary works, will know what others have said about them, so you need to be extra careful not to plagiarize their ideas or words.)

The Conclusion: Restate Your Thesis

Your conclusion should bring your readers’ attention back to the thesis that you expressed in the introduction. Your conclusion should also point the reader in new directions. Up to this point in the literary analysis, your readers will expect you to closely follow the text. In the conclusion, though, they will allow more leeway. In a sense, you’ve earned the right to speculate and consider other ideas. So, if you want, take on the larger issues that were dealt with in this literary work. What conclusions or questions does your analysis suggest? What challenges does the author believe we face? What is the author really trying to say about people, events, and the world we live in?

Choosing an Appropriate Style

Literary analyses invite readers into a conversation about a literary work. Therefore, the style should be straightforward but also inviting and encouraging.

Use the “Literary Present” Tense

Describe the text, what happens, and what characters do as though the action is taking place at the present moment. Here are two examples that show how to use the literary present:

Examples

Louise Mallard is at first grief-stricken by the news of her husband’s death, but her grief fades and turns into a sense of elation.

While many of Langston Hughes’s poems recount the struggles of African-Americans, they are often tinged with optimism and hope.

When discussing the author historically, however, use the past tense.

Examples

Of course, Chopin knew nothing about the discoveries made by modern scientists, but she did understand human nature and how we are driven to search for meaning.

Langston Hughes was well known in his time as a Harlem Renaissance poet. He often touched on themes of equality and expressed a guarded optimism about equality of treatment for all races.

Integrate Quoted Text

Weave words and ideas from the literary text in with your words and ideas, and avoid quotations that are not directly related to your ideas. For example, you can include a quotation at the end of your own sentence:

Example

You could also take the same sentence from the story and weave a “tissue” of quotations into your words:

Example

Make sure any sentences that include quotations remain grammatically correct. When you omit words from your quotation, use ellipses. Also, whenever you take a quote from the text, explain how the quotation supports the point you are trying to make. Don’t leave your readers hanging with a quotation but no commentary. Tell them what the quote means and be clear about why you used it.

Move Beyond Personal Response

Literary analyses are always partly personal, but your personal response is not enough. While your professor may encourage you to delve into your personal reactions in your response papers, your literary analysis should move beyond that personal response to a discussion of the literary work itself. In other words, describe what the text does, not just how you personally react to it. Keep in mind that literary analyses are interpretive and speculative, not absolute and final. When you want your readers to understand that you are interpreting, use words and phrases such as “seems,” “perhaps,” “it could be,” “may,” “it seems clear that,” and “probably.”

Example

Designing Your Literary Analysis

Typically, literary analyses use a simple and traditional design, following the MLA format for manuscripts: double-spaced, easy-to-read font, one-inch margins, and MLA documentation style (see Section V). Always consult with your professor about which format to use.

Headings and graphics are becoming more common in literary analyses. Before you use headings or graphics, ask your professor if they are allowed in this class. Headings will help you organize your analysis and make transitions between larger sections. In some cases, you may want to add graphics, especially if the literary work you are analyzing uses illustrations or if you have a graphic that would illustrate or help explain a key element in your analysis.

Design features like headers and page numbers are usually welcome, because they help your professors and your classmates keep the pages in order. Also, if you are asked to discuss your work in class, page numbers will help the class easily find what is being discussed.

Microgenre: Gender Analysis

When it comes to analyzing literature, what you write about in your essay is determined by literary theory. There are different literary theories or schools of literary criticism to choose from. The Purdue Online Writing Lab (OWL) describes literary theories this way:

A very basic way of thinking about literary theory is that these ideas act as different lenses critics use to view and talk about art, literature, and even culture. These different lenses allow critics to consider works of art based on certain assumptions within that school of theory. The different lenses also allow critics to focus on particular aspects of a work they consider important. For example, if a critic is working with certain Marxist theories, s/he might focus on how the characters in a story interact based on their economic situation. If a critic is working with post-colonial theories, s/he might consider the same story but look at how characters from colonial powers (Britain, France, and even America) treat characters from, say, Africa or the Caribbean.

Gender Studies (previously called Women’s Studies or Feminist Studies) is one of these lenses. Gender studies focuses on the role of gender in a literary text. It is useful for analyzing how gender itself is socially constructed for both men and women. Gender studies also considers how literature upholds or challenges those constructions, offering a unique way to approach literature. A gender analysis explores issues of sexuality, power, and marginalized populations (woman as other) in literature and culture. In The Critical Tradition: Classic Texts and Contemporary Trends, literary scholar David H. Richter wrote that this literary theory evolved from previous literary and culturally significant discussions:

Effective as [feminism] was in changing what teachers taught and what the students read, there was a sense on the part of some feminist critics that…it was still the old game that was being played, when what it needed was a new game entirely. The argument posed was that in order to counter patriarchy, it was necessary not merely to think about new texts, but to think about them in radically new ways (1432).

- examines the differences in women’s and men’s lives, including those which lead to social and economic inequity for women, and applies this understanding to policy development and service delivery

- is concerned with the underlying causes of these inequities

- aims to achieve positive change for women

While gender refers to the social construction of female and male identity, it is more than biological differences between men and women. It includes the ways in which those differences, whether real or perceived, have been valued, used, and relied upon to classify women and men and to assign roles and expectations to them. The significance of this is that the lives and experiences of women and men, including their experience of the legal system, occur within complex sets of differing social and cultural expectations.

- women’s and men’s lives and therefore experiences, needs, issues and priorities are different

- women’s lives are not all the same; the interests that women have in common may be determined as much by their social position or their ethnic identity as by the fact they are women

- women’s life experiences, needs, issues and priorities are different for different ethnic groups

- the life experiences, needs, issues, and priorities vary for different groups of women (dependent on age, ethnicity, disability, income levels, employment status, marital status, sexual orientation and whether they have dependents)

- different strategies may be necessary to achieve equitable outcomes for women and men and different groups of women

- Gender equality is based on the premise that women and men should be treated in the same way. This fails to recognize that equal treatment will not produce equitable results, because women and men have different life experiences.

- Gender equity takes into consideration the differences in women’s and men’s lives and recognizes that different approaches may be needed to produce outcomes that are equitable.

Gender analysis provides a basis for robust analysis of the differences between women’s and men’s lives, and this removes the possibility of analysis being based on incorrect assumptions and stereotypes.

At this point, you may be wondering, what is gender exactly? It’s a term that we are all used to hearing, but the definition and the concept as it applies to literature are more complicated than you may realize. Click here to view a Prezi presentation on gender and its role in society.

Breaking the Disney Spell by Jack Zipes

Literary Analysis Example #1: “Harry Potter’s Girl Trouble” by Christine Schoefer (Salon 13 January 2000)

The World of Everyone’s Favorite Kid Wizard is a Place Where Boys Come First

Four factors made me go out and buy the Harry Potter books: Their impressive lead on the bestseller lists, parents’ raves about Harry Potter’s magical ability to turn kids into passionate readers, my daughters’ clamoring and the mile-long waiting lists at the public library. Once I opened “The Sorcerer’s Stone,” I was hooked and read to the last page of Volume 3. Glittering mystery and nail-biting suspense, compelling language and colorful imagery, magical feats juxtaposed with real-life concerns all contributed to making these books page-turners. Of course, Diagon Alley haunted me, the Sorting Hat dazzled me, Quidditch intrigued me. Believe me, I tried as hard as I could to ignore the sexism. I really wanted to love Harry Potter. But how could I?

Harry’s fictional realm of magic and wizardry perfectly mirrors the conventional assumption that men do and should run the world. From the beginning of the first Potter book, it is boys and men, wizards and sorcerers, who catch our attention by dominating the scenes and determining the action. Harry, of course, plays the lead. In his epic struggle with the forces of darkness — the evil wizard Voldemort and his male supporters — Harry is supported by the dignified wizard Dumbledore and a colorful cast of male characters. Girls, when they are not downright silly or unlikable, are helpers, enablers and instruments. No girl is brilliantly heroic the way Harry is, no woman is experienced and wise like Professor Dumbledore. In fact, the range of female personalities is so limited that neither women nor girls play on the side of evil.

But, you interject, what about Harry’s good friend Hermione? Indeed, she is the female lead and the smartest student at Hogwart’s School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. She works hard to be accepted by Harry and his sidekick Ron, who treat her like a tag-along until Volume 3. The trio reminds me of Dennis the Menace, Joey and Margaret or Calvin, Hobbes and Suzy. Like her cartoon counterparts, Hermione is a smart goody-goody who annoys the boys by constantly reminding them of school rules. Early on, she is described as “a bossy know-it-all,” hissing at the boys “like an angry goose.” Halfway through the first book, when Harry rescues her with Ron’s assistance, the hierarchy of power is established. We learn that Hermione’s bookish knowledge only goes so far. At the sight of a horrible troll, she “sinks to the floor in fright … her mouth open with terror.” Like every Hollywood damsel in distress, Hermione depends on the resourcefulness of boys and repays them with her complicity. By lying to cover up for them, she earns the boys’ reluctant appreciation.

Though I was impressed by Hermione’s brain power, I felt sorry for her. She struggles so hard to get Harry and Ron’s approval and respect, in spite of the boys’ constant teasing and rejection. And she has no girlfriends. Indeed, there don’t seem to be any other girls at the school worth her — or our — attention. Again and again, her emotions interfere with her intelligence, so that she loses her head when it comes to applying her knowledge. Although she casts successful spells for the boys, Hermione messes up her own and as a result, while they go adventuring, she hides in the bathroom with cat fur on her face. I find myself wanting Hermione to shine, but her bookish knowledge and her sincere efforts can’t hold a candle to Harry’s flamboyant, rule-defying bravery.

Even though Hermione eventually wins the boys’ begrudging respect and friendship, her thirst for knowledge remains a constant source of irritation for them. And who can blame them? With her nose stuck in books, she’s no fun. Thankfully, she is not hung up on her looks or the shape of her body. But her relentless studying has all the characteristics of a disorder: It makes her ill-humored, renders her oblivious to her surroundings and threatens her health, especially in the third volume.

Ron’s younger sister Ginny, another girl student at Hogwart’s, can’t help blushing and stammering around Harry, and she fares even worse than Hermione. “Stupid little Ginny” unwittingly becomes the tool of evil when she takes to writing in a magical diary. For months and months, “the foolish little brat” confides “all her pitiful worries and woes” (“how she didn’t think famous good

great Harry Potter would ‘ever’ like her”) to these pages. We are told how boring it is to listen to “the silly little troubles of an eleven-year-old girl.”

Again and again, we see girls so caught up in their emotions that they lose sight of the bigger picture. We watch them “shriek,” “scream,” “gasp” and “giggle” in situations where boys retain their composure. Again and again, girls stay at the sidelines of adventure while the boys jump in. While Harry’s friends clamor to ride his brand-new Firebolt broomstick, for example, classmate Penelope is content just to hold it.

The only female authority figure is beady-eyed, thin-lipped Minerva McGonagall, professor of transfiguration and deputy headmistress of Hogwart’s. Stern instead of charismatic, she is described as eyeing her students like “a wrathful eagle.” McGonagall is Dumbledore’s right hand and she defers to him in every respect. Whereas he has the wisdom to see beyond rules and the power to disregard them, McGonagall is bound by them and enforces them strictly. Although she makes a great effort to keep her feelings under control, in a situation of crisis she loses herself in emotions because she lacks Dumbledore’s vision of the bigger picture. When Harry returns from the chamber of secrets, she clutches her chest, gasps and speaks weakly while the all-knowing Dumbledore beams.

Sybill Trelawney is the other female professor we encounter. She teaches divination, a subject that includes tea-leaf reading, palmistry, crystal gazing — all the intuitive arts commonly associated with female practitioners. Trelawney is a misty, dreamy, dewy charlatan, whose “clairvoyant vibrations” are the subject of constant scorn and ridicule. The only time she makes an accurate prediction, she doesn’t even know it because she goes into a stupor. Because most of her students and all of her colleagues dismiss her, the entire intuitive tradition of fortune-telling, a female domain, is discredited.

A brief description of the guests in the Leaky Cauldron pub succinctly summarizes author J.K. Rowling’s estimation of male and female: There are “funny little witches,” “venerable looking wizards” who argue philosophy, “wild looking warlocks,” “raucous dwarfs” and a “hag” ordering a plate of raw liver. Which would you prefer to be? I rest my case.

But I remain perplexed that a woman (the mother of a daughter, no less) would, at the turn of the 20th century, write a book so full of stereotypes. Is it more difficult to imagine a headmistress sparkling with wit, intelligence and passion than to conjure up a unicorn shedding silver blood? More farfetched to create a brilliant, bold and lovable heroine than a marauder’s map?

It is easy to see why boys love Harry’s adventures. And I know that girls’ uncanny ability to imagine themselves in male roles (an empathic skill that boys seem to lack, honed on virtually all children’s literature as well as Hollywood’s younger audience films) enables them to dissociate from the limitations of female characters. But I wonder about the parents, many of whom join their kids in reading the Harry Potter stories. Is our longing for a magical world so deep, our hunger to be surprised and amazed so intense, our gratitude for a well-told story so great that we are willing to abdicate our critical judgment? Or are the stereotypes in the story integral to our fascination — do we feel comforted by a world in which conventional roles are firmly in place?

I have learned that Harry Potter is a sacred cow. Bringing up my objections has earned me other parents’ resentment — they regard me as a heavy-handed feminist with no sense of fun who is trying to spoil a bit of magic they have discovered. But I enjoyed the fantastical world of wizards, witches, beasts and muggles as much as anyone. Is that a good reason to ignore what’s been left out?

Literary Analysis Example #2: “The Empowered ‘Snow White’” by Monica Hesse (Washington Post 1 June 2012)

A Bad Apple in Modern Film Typecasting

Philosophical questions: 1. Would a rose by any other name smell as sweet? And, 2. Is a Snow White wearing a metal breastplate and brandishing a sword still “Snow White”?“Snow White and the Huntsman” stampeded into theaters Friday to mixed — often fawning — critical reviews, but the movie has a fairly open relationship with the original Grimms’ fairy story. Not because there are eight dwarfs instead of seven, or because the Wicked Queen has a superfluous brother, or because there’s a random scene in which a Christlike stag magically turns into a cloud of butterflies. Those are the sorts of minor changes that nag at fangirls.

But when Snow White storms a castle, and Snow White learns to fight, and Snow White (spoiler alert!) ends up choosing neither of her two male suitors, preferring to sit on a throne alone — well, perhaps we should at least call the girl Snow Whitish, or maybe Snow Ecru. Or just rename the altered product, “Princess on a Fast Horse, Also Tames Trolls.”

It’s not a new observation that entertainment screens have been subjected to recent fairy-bombings: TV shows “Once Upon a Time” and “Grimm,” and a cinematic deluge that began with Tim Burton’s “Alice in Wonderland” and included this spring’s “Mirror, Mirror,” another Snow interpretation.

The new adaptations have ranged from silly (“Mirror”) to slutty (“Red Hiding Hood”) but what they have in common is the boldfaced empowerment — or “empowerment” — bestowed upon the female protagonists. Amanda Seyfried’s Red Riding Hood didn’t need a woodsman to kill the wolf; she handily took care of that on her own. Mia Wasikowska’s Alice slew the Jabberwocky and opened trade routes to China. Lily Collins’s Snow White knew a bad apple when she saw one, so she fed it to Julia Roberts instead.

Yay for feminism, yay for fight scenes, yay for girls who know better than to lie around waiting for a lover’s kiss to wake them from a coma — because honestly, in modern times that scene looks like a date-rape PSA waiting to happen.

“It’s a desire to do a role reversal,” says Brian Sturm, a professor at the University of North Carolina who co-wrote the scholarly article “We Said Feminist Fairy Tales, Not Fractured Fairy Tales!” It’s a course correction — a way of acknowledging that misogyny in old bedtime stories should be put to sleep.

But sometimes Sturm wonders how well the course correction works. These strong-female updates often don’t create more complex characters, he says, but rather just pretend that a random sword can negate hours of eye-batting.

Because Snow White’s defining characteristics are her kindness and compassion to animals (just as Cinderella’s was her work ethic, and Red Riding Hood’s was her sense of familial duty), then why not have her use those strengths to defeat the queen? Why not have her rally a flock of birds to dive-bomb the magic mirror room? There are ways to update fairy tales that don’t lose the integrity of the original character. But when Kristen Stewart spends the first half of “Snow White” charming woodland creatures and then spends the second half slipping into chain mail for a hero’s run, that’s not creating a more three-dimensional Snow White. That’s replacing Snow White mid-movie with Katniss Everdeen.

Of course, the “original” Snow White would be barely recognizable now. The 1937 Disney version omitted the gore of the Grimms’ version — poison combs, stifling corsets — and even the Brothers Grimm revised the tale several times. In their original “Snow White,” published 200 years ago in 1812, there was no wicked stepmother. It was the mother who was wicked; she wanted to murder her own too-beautiful child. The Grimms changed it for later editions.

Snow White “has become a very important meme,” says Jack Zipes, a renowned folklore and fairy-tale scholar, because it’s been used to reflect societal concerns. To Zipes, a successful retelling of the story would be one that accurately reflected women’s struggles and issues today. “Snow White and the Huntsman” doesn’t, he says.

It’s just Kristen Stewart, eight pudgy dwarfs and a monumentally screwed-up stepmom relationship that pits women against women and calls it feminist.

If we can’t find a way to stop mangling old fairy-tale tropes, maybe we can find a way to invent better ones. After all, how many times must a story be crossed out and rewritten before someone should just get a fresh sheet of paper and write something new?

Literary Analysis Example #3: “Finding the Glass Slipper” by Kathryn Buckingham (Elon University 2016)

A Feminist Analysis of the Disney Princess Films

Abstract

This research studied Walt Disney’s female representation within the Disney Princess franchise. With the princess movies’ target audience being very young and impressionable, it’s important to understand how female characters are being presented. With that, it is important to see how it has changed over the years. The study was done by performing a content analysis of the Disney Princess films, through the application of the Bechdel test. Then through an extension of the test, the types of relationships found in the films were analyzed. Along with the content analysis, a critical analysis was applied to the films in order to better examine some of the female relationships. The critical analysis was supplemented by the use of secondary sources from the literature review. The findings of the research demonstrated that the majority of Disney’s Princess movies passed the Bechdel test, but did not consistently have good female relationships or representation.

Introduction

Over the years, the Walt Disney Company has been known for its Disney princess franchise. From Snow White to Rapunzel, Disney has managed to cover almost every fairy tale. While the stories are beloved by children around the world, Disney has often received criticism for its handling of female characters. At a grand total of eleven princesses (with soon to be two more added), the Disney Princess franchise is one of Disney’s most popular sources of entertainment. However, since Disney’s Mulan in 1998, we’ve seen a decline in not only the Disney princess franchise, but also in female-lead films from the Disney Company. The next did not appear until eleven years later, with Disney’s film The Princess and the Frog. However, during this gap, it was not just an absence of princesses that was happening. Pixar Animation had its strongest run during 1998–2009, producing major blockbuster animations such as Finding Nemo (2003) and Up (2009). It was 2013’s Frozen that catapulted Disney back into the spotlight, featuring not just one princess, but two, in an action-packed musical. The story features two sisters who have to embark on a journey to find themselves and each other in order to save their city. Frozen dominated the theaters, bringing in a total of $1.072 billion worldwide (McClintock, 2013). This study focuses on Disney’s handling of its female characters over the years and the changes to it with more modern characters. In relation to that, it applies popular feminist media critique, the Bechdel test, to see how Disney has represented female characters in its forever-popular Disney Princess movies. The study will examine all twelve of the Disney Princess films of the franchise and attempt to discover how good of an example Disney is setting for young audiences that watch these films.

Literature Review: Disney the Company

Walt Disney began his career in the late 1920s, and ended up creating a “multifaceted entertainment enterprise—short cartoons, feature-length animations, live-action films, comic books and records, nature documentaries, television shows, colossal theme parks” ( Walt Disney, 1995). Often Disney was called an “artistic genius and a modernist pioneer” ( Walt Disney, 1995). As Disney continued to grow in popularity, it became “a symbol for the security and romance of the small-town America of yesteryear—a pristine never-never land in which children’s fantasies come true, happiness reigns, and innocence is kept safe through the magic of pixie dust” (Giroux & Pollock, 2010, p. 17). In 2006, Disney “announced that it [was] buying Pixar, the animated studio led by Apple head Steve Jobs, in a deal worth $7.4 billion” (Monica, 2006). This was a strategic move on the part of Disney, based on how Pixar had “yet to have a flop with its six animated movies . . . gross[ing] more than $3.2 billion worldwide, according to movie tracking research firm Box Office Mojo” (Monica, 2006). Pixar would later go on to make the movie Brave in 2012, featuring one of Disney’s newer official Disney princesses.

Disney’s Handling of Female Characters

Just as feminism has changed and developed over the years, so has Disney’s portrayal of female characters. Categorically, Disney films can be separated into different eras based on when they were made, making it easier to see the progress that has been made. The belief is that Disney shows that women can be successful if “they firmly believe in themselves—as individuals and as women” (Brode, 2005, p. 171). According to Disney’s website for the official princesses, there are currently eleven princesses. The classic heroines from Disney’s princess lineup are typically considered to be Snow White from Snow White (1937), Cinderella from Cinderella (1950), Aurora from Sleeping Beauty (1959), Ariel in The Little Mermaid (1989), Bell in Beauty and the Beast (1991), Pocahontas (1995), and Mulan in Mulan (1998); followed up by their later counterparts Tiana from Princess and the Frog (2009), Rapunzel in Tangled (2010), and Merida in Brave (2012). They will later be joined by Elsa and Anna from Frozen (2013), though they have not yet been initiated into the official line up. There is current speculation that by the end of 2014, the two princesses will be officially added to the lineup, creating princesses number twelve and thirteen. There is an importance to the Walt Disney Company and how they present their media, as well as the ability to critique it, due to the “expanding role [it] plays in shaping popular culture and broader public discourse” (Giroux, 2010, p. xiii). Disney has created a persona that has become synonymous with “childhood innocence and wholesome entertainment” (Giroux, 2010, p. xiii). Disney as a whole made over $37.8 billion in revenue in 2008 making it an extremely powerful business (Giroux & Pollock, 2010, p. 93). Henry Giroux and Grace Pol-lock stress in their book, The Mouse That Roared, that “it is imperative that parents, teachers, and other adults understand how [Disney’s] animated films influence the values of the children who view them” (2010, p. 97). Haseenah Ebrahim agrees in his article, “Are the ‘Boys’ at Pixar Afraid of Little Girls?,” commenting on the fact that critique is good and necessary, and it is “the Disney princesses who continue to garner the most attention, both scholarly and popular” (2014, p. 45).

The difficulty in analyzing Disney’s female characters is choosing which interpretation to take when studying them. For instance, Disney’s Mulan is often considered one of its most successful Disney princess movies, featuring a strong, independent young woman who defies the boundaries placed on her gender and helps save her country. The argument against Mulan as a strong female character comes in that her transformation to a man actually “supports patriarchal power structures rather than disputes established gender roles” (Cheu, 2013, p. 115) and that it “contains the disruption that arises when a woman becomes a man to reinforce the gender binary and deny any agency” (Cheu, 2013, p. 116). Much like Lady Macbeth’s symbolic transformation in William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Mulan must shed her own femininity and appear as a man in order to be successful. Mulan does successfully show the dangers of societal pressures on women, such as the scene with the song “Honor to Us All,” where Mulan is led to the matchmaker and it is defined that in her culture, “a daughter can only bring honor to herself and her family by becoming a bride. Without fulfilling her assigned gender role . . . her family [will] merit no honor” (Cheu, 2013, p. 117). As Sam Abel says in his article cited in Cheu’s book, Disney “cannot critique traditional gender roles because [it] buy[s] into them” (1995). So while Mulan remains a progressive film and represents a more positive female character, there is still hesitancy behind Disney’s plot, having a give-and-take situation in which there is an improved female character but a lack in challenging the status quo.

The different interpretations of Disney princesses extend to the very first one as well, Snow White. While her character is often seen as soft and domestic, Douglas Brode describes her as “formidable” (2005, p. 180). According to him, the power in Snow White is that she “makes her own decisions, redeeming housework from mere drudgery,” making a point that “housework is equal in value to any labor performed ‘in the world’—that, in fact, the home is a part of that world, and the work done there equal in validity to anything achieved in an office” (Brode, 2005, p. 178–179). These interpretations, however, are some of the few more positive ones seen speaking in favor of Snow White’s character. Jacqueline Layng criticized Disney for its portrayal of Snow White. While Brode argues in favor of the soft-spoken character, Layng calls out how “Snow White never acts to help herself” (2001) and gives examples such as covering her face and screaming when threatened by the hunts-man and that “when in a sleeping death, she can only be saved by the prince” (2001). This idea that the prince must kiss her to awaken her plays with the theme of what is seen as a popular theme in Disney romance—the no-means-yes scenario. In the case of Snow White, this theory applies to the idea that “the object of the prince’s desire is unavailable yet tantalizingly visible: a beautiful woman encased in a glass coffin” (Bean, 2003, p. 60). This contrast in character interpretation is extended to more modern princesses as well, such as Disney’s Aladdin, Princess Jasmine. While Disney portrays Jasmine in a strong light as independent and a freethinker with a thirst for freedom, her character battles “between what she says and what she does” (Layng, 2001). While she does run away from the male figures in her life, her freedom is cut short and she returns to her home, only to be saved in the end by Aladdin. Layng compares these two seemingly very different princesses, Snow White and Jasmine, and concludes that in regard to both character arcs, “Disney’s answer for women today is same as it was in 1937—marry the right man and live happily ever after” (2001). Along with that, she determined that “dependency is a consistent theme, as both ‘heroines’ are required to rely on heroes to save them” (Layng, 2001). In regard to the interpretation of Belle from Beauty and the Beast, there are similarly different ways to look at her character. Unlike the majority of the princess characters at the time, Belle retains no interest in marriage and instead is fixated on knowledge. She is a “smart, independent young woman” (Manley, 2003, p. 79) and a “better role model than the marriage-minded Disney heroines of the past” (Manley, 2003, p. 79). There is, however, one negative female character stereotype that she falls dangerously near—woman as a civilizing force. This is the idea that a woman must take care of male characters or that it is her role to tame the wilder, immature man (Manley, 2003, p. 83–84). The danger of this type of role is that:

women may believe their role in a relationship with a man is to mother him, or be a model of civilized behavior, or both. It may also cause women to have an unrealistic belief in their ability to reform a man who treats them badly . . . though the woman might feel like a powerful agent . . . she is constrained by a role which requires certain behaviors from her. (Manley, 2003, p. 88)

In his research article, “Are the ‘Boys’ at Pixar Afraid of Little Girls?,” Haseenah Ebrahim addresses Pixar’s handling of female characters. While Disney currently owns Pixar, the two have worked as separate companies and handle their female characters differently. Brave was Pixar’s “first film with a female protagonist,” (2014) sending “Internet bloggers, animation and film Web sites, feminists, Pixar fans, newspapers, magazine columnists, and entertainment TV channels” (Ebrahim, p. 44) into huge discussions about what “this departure from the animation studio’s well-established record of highly successful male-centric fare would mean” (Ebrahim, p. 44). Brave director, Brenda Chapman, is also the first woman to direct any of Pixar’s films (Ebrahim, 2014, p. 46). Besides having very few female characters, Pixar also chooses to focus its plots on male bonding as a “conspicuous theme of Pixar films,” (Ebrahim, 2014, p. 44) and “after twelve noteworthy animated features Pixar had avoided making a female a protagonist in any of its films” (Ebrahim, 2014, p. 44). When referring to Rapunzel and Tiana (princesses of Tangled and The Princess and the Frog respectively), Ebrahim acknowledged their strength as modern princesses as being “independent, intelligent young women actively pursuing their goals,” but that this was then sacrificed as they were “forced to share most of their screen time with their respective love interests” (2014, p. 46). Brave is now the only Princess film to have been made without a love interest. The consistent theme of a love interest runs through almost all of the Disney Princess films, even in Brave where there isn’t a direct romantic partner but the story’s plotline is initiated from not necessarily a lack of female characters. However their story arcs are often tied to a romance-based plotline and “little attention is paid to female characters that are not the protagonists or the main love interest of the protagonist, even though the Disney animation universe is populated with a considerable number of human female characters” (Ebrahim, 2014, p. 44). With the focus primarily on romance in the different plots, Disney sends the message that “marriage represents the inevitable reward of the righteous and properly catechized woman” (Bean, 2003, p. 53).

The Background and Success of Disney’s Frozen

In 2013 Disney released one of the most successful movies, animated or live action. Frozen is a retelling of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Snow Queen, and features young princess Anna on a mission to save her older sister from herself and to save their city. Elsa’s ice powers appear to both be a blessing and a curse as she struggles to learn control and what it means to let go (a perfect theme utilized in her breakthrough solo, “Let It Go”). As of March 30, 2014, Frozen had “earned $398.4 million domestically and $674 million internationally for a total $1.072 billion” (McClintock, 2014). At the time that Pamela McClintock wrote her article for The Hollywood Reporter, Frozen had “become the top-grossing animated film of all time” and “internationally, . . . the biggest Disney or Pixar animated film of all time in 27 territories, including Russia, China and Brazil” (2014). Amongst the high box office ratings, Frozen “directed by Chris Buck and Jennifer Lee, claimed the best animated film Oscar at [the 2014] Academy Awards” (McClintock, 2014). Movie critics gave Frozen high praise, also drawing high acclaim from a feminist perspective. In her movie review for Frozen, Durga M. Sengupta (2013) cited writer Linda Barnard’s positive critique:

(Frozen) makes it clear that girls . . . may want to rethink the fairy tale and opt for self-reliance . . . Welcome to Disney 2.0, which has learned from the box office success of Tangled and last year’s Brave, that kids are demanding a lot more from their cartoon princesses these days . . . these two even pass the Bechdel test for feminism on film, where two women talk to each other about something other than a man. Make way for a new kind of fairy tale (Barnard, 2013).

Frozen seemed to be a great step in the right direction for Disney in regard to female characters, building off of the strength of the recent, but less popular, princess movies. There was a double dose of female power with the sisters who give strong images of independence as well as being very much their own person, including personal growth as the movie goes on. Besides quips such as “You can’t marry a man you just met,” from the character Elsa (Frozen, 2013), a stark contrast and slight nod to early Disney films, there are a lot of good moments between the female characters. The emphasis on the sister relationship stems from the basis of the plot. The younger of the princesses, Anna, spends the movie looking for her sister and not only to help save the kingdom, but also to save their relationship. Their story arc primarily focuses on them versus a romantic storyline, and they grow as independent characters rather than based on interactions with their male counterparts.

The Bechdel Test and Feminist Film Analysis

A common tool in feminist critique is the use of the Bechdel Test. The test is most commonly “used to gauge gender bias in fiction, including comics and graphic novels” (Møllegaard, 2014). The test’s origins come from a comic created by cartoonist, Alison Bechdel in a 1985 comic strip called Dykes to Watch Out For. In the comic strip, a female character is describing to another what she looks for in a movie and what her rules are in order for her to watch it. These rules then evolved into what is now known as the “Bechdel Test.” According to Bechdel, in order for a movie to have adequate female representation and pass the test, it must meet these three requirements:

1. It includes at least two women,

2. Who have at least one conversation,

3. About something other than a man or men.

While a seemingly simple test, even modern films are rarely successful in checking off each of the three requirements. And while films can pass the Bechdel Test in regard to female character interaction, the test does not have a way to measure or demonstrate that the female characters are good representation. Though missing this element, the test is still seen as an important step in improving equality in media. The Bechdel Test has been critiqued, and Møllegaard points this out in her article, answering her own question with, “Is the Bechdel Test applicable to anthologies of academic writing? Probably not without some serious caveats” (2014). Due to the test not being an end-all for feminist critique, various versions and expansions have been created to help sup-ply further critique. A recent one that came out was inspired by female sci-fi fans, called the Mako Mori Test, “named after the sole female lead in . . . blockbuster Pacific Rim—which, not incidentally, failed the Bechdel Test itself” (John, 2013). This test has its own set of three rules:

1. Has at least one female character,

2. Who gets her own narrative arc,

3. That is not about supporting a man’s story.

In Arit John’s article for The Wire on the Bechdel Test and the Mako Mori Test, he included a quote from one of the original women who helped give input on the popular blogging platform Tumblr, about the importance of a test that reaches farther than the Bechdel Test:

It’s really easy to throw away a film because of that test (which is flawed and used incorrectly in a lot of ways) if you’re a white woman and can easily find other films with white women who look like you and represent you. . . . But as an East Asian woman, someone like Mako—a well-written Japanese woman who is informed by her culture without being solely defined by it, without being a racial stereotype, and gets to carry the film and have character development—almost NEVER comes along in mainstream Western media. (John, 2014)

This research seeks to answer the question, how has Disney’s female representation changed in the Disney Princess franchise over the years? Through a feminist analysis and critique, has Disney presented an overall negative or positive image of female characters?

Methods

This study will use two different methods of analysis, a critical analysis of secondary sources and a content analysis of Disney’s official princess films. The method of a quantitative analysis was chosen to help see if there has been a progression of positive female representation in Disney’s princess films over the years. This content analysis, applying the Bechdel Test to each film, will help give an idea of how the representation of women has changed over the years, or possibly has not changed. The critical analysis will take different sources that have studied different aspects of the questions presented by the study in an attempt to come to a conclusion of how Disney and its female characters have been changed by the influence of the comic book industry and whether it is a positive or negative outcome.

The Sample

The first part of the study analyzes Disney’s female representation, specifically the movies that are considered to be Disney’s official princesses. The movies selected were taken from Disney’s official Princess website.

Because this study focuses on the idea of the Disney princesses versus the superhero movement, these were the more critical films to analyze instead of simply all of Disney’s films. The princess films are also typically seen as the most popular and influential Disney films when it comes to younger girls. The importance of progress in female representation is more crucial in the franchise that draws the most attention. The amount of exposure that the princess films receive outweighs other Disney films that could have an influence on a younger audience.

The Procedure

Taking the Disney films that were designated as official Disney films, they were then analyzed in an extended version of the Bechdel Test. The basis of the test was the original version of the Bechdel Test, and included the requirement that the characters must be named to count for the test. After first noting the year the film was made, each film was put through a pass/fail analysis of the extended version of the Bechdel Test:

1. It includes at least two named women,

2. Who have at least one conversation,

3. About something other than a man or men.

If the movie passes at least the first test, it then is analyzed based on the general type of relationship of the women in the film. Like the pass/fail analysis of the first portion of the test, it will be marked as a positive, neutral, or a negative relationship. Because there can be room for interpretation of what is positive, neutral, or negative, these terms will be used as a basic guide for if the relationship shows a general representation of the terms’ connotations. The type of relationship classification was designed to cover that while two female characters might speak in a movie, it might be for a limited amount of time or only happen once. These conclusions were reached based on the different interactions with the female characters and the strength of their type of involvement. If the interaction was limited and/or one-sided (brief or only pertained to a villain and the main character), then it was classified as negative. The flaw of the original test is that it does not cover this possibility, so the researcher added these sections to analyze the type of relationship. There will also be a count of the female characters in each movie, a number that will be generated by focusing on the female characters that have speaking roles and/or are main characters in the movie. This will then be compared to the total number of speaking/main characters to see how the ratio balances out. This will help show if there is a true balance of characters due to that while in some stories there might only be three speaking female characters, there might only be a total of seven main characters. By finding the ratio it will help give a better idea of the strength of the female representation.

Analysis

While the content analysis will help give a rough idea if there has been a positive or negative trend in female representation in the Disney Princess movies, it is not a perfect system to use for feminist analysis. The Bechdel Test focuses on statistical data, but the addition to it sup-plied in the study still does not adequately measure the success of female representation. This will instead give a general idea of how each film does, and a deeper study would be required to truly see the improvements and failings of the movies. Stronger feminist analysis breaks down individual movies and analyzes the characters and their portrayals and interactions to better learn how the movie does involving its female characters. The critical analysis of the secondary sources will require reaching a conclusion based on various, separate sources. Due to not every source being connected, this section of the findings will be based on the conclusions that are independently reached by the researcher. The conclusion will be based on different readings covering the topics listed in the literature review.

Findings

In order to see the success of the relationships of female characters in the Disney Princess movies, a content analysis was performed for each movie. The first test focused on the Bechdel Test.

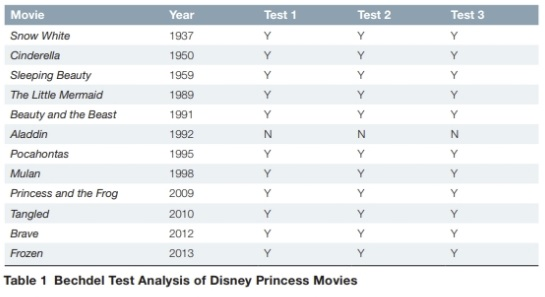

As a whole, the results of the research shown in Table 1 demonstrate that the Disney Princess movies overwhelmingly passed the Bechdel Test. Out of the twelve movies, only one (Aladdin) failed. On the surface, these results are positive. These numbers show that 11 out of 12 Disney Princess movie features have at least two named female characters who at some point, talk about something other than a man/men. This test, however, is relatively simplistic when it comes to analyzing female representation and relationships, so the author then applied an extended content analysis, as described in the previous Methods section.

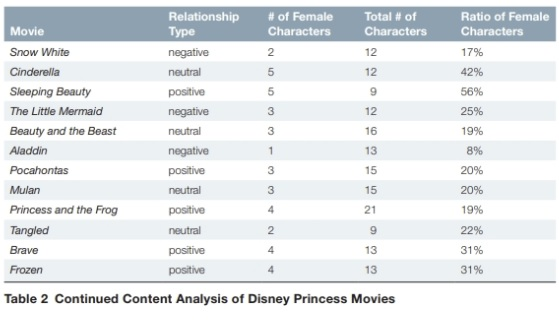

Table 2 shows a breakdown of the different types of relationships in the Disney movies. The first analysis was based on the views of the relationship demonstrated as positive, negative, or neutral. Most of the movies were found to be positive or neutral, with only Aladdin, Snow White, and The Little Mermaid being classified as portraying negative types of relationships. In the case of Aladdin, it is automatically considered negative because it was unable to pass the original Bechdel Test. The ratio of the female characters to the total number of char-acters helped give an idea of the statistical representation of female characters. Movies like Snow White and Aladdin have the lowest percentage of female characters, whereas films like Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty have the highest.

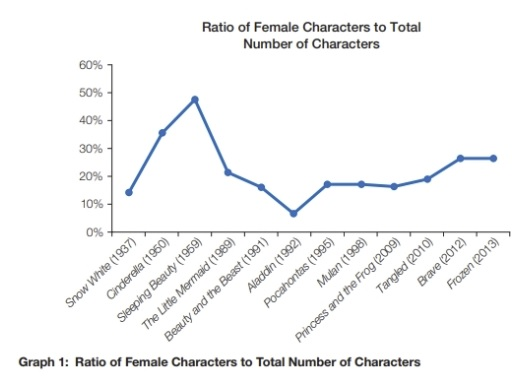

Graph 1 represents the changes in percentage of female representation over the years. It chronologically orders the movies with the year they were released while comparing the percentage amount for each one over the years. While Disney’s best female represented film is actually Sleeping Beauty from 1959, there has been an overall increase in the ratio of female characters in the past two decades—specifically after 1992 when Disney had its lowest female representation in the movie Aladdin. This steady increase comes after a dramatic decline in the movies between Sleeping Beauty and Aladdin. Because the movies are organized sequentially in order of when they were made, this shows a positive trend going into the future for Disney.

Conclusions

While this data does show different trends and other quantitative data for the movies, it is not a complete way to analyze the strength of female representation in Disney’s Princess films. The Bechdel Test is a good starting point to ensure that there is a balanced amount of female characters in movies and to guarantee that they do have some type of relationship, even if it is positive or negative. However, doing a purely numbers-based content analysis removes aspects of some of the characters and stories that otherwise might be good representation. As an example, Sleeping Beauty passes the Bechdel Test with flying colors and has the highest percentage of female characters, but is not considered a strong example of a good feminist film in regard to how the female characters are portrayed. While not necessarily a bad character, Aurora is an extremely flat character. When she is not singing or dancing, she is sleeping.

Her importance lies in her beauty and does not inspire as a good representation of a woman. However, her counterpart, Maleficent, is one of the stronger Disney villains regardless of gender. Her cunningness and strategy makes her a force to be reckoned with and stands as a strong female character. The importance of good female characters does not necessarily mean that they all represent good people, but that they are complex and more than just a caricature of female stereotypes.

A similar critique can be applied to Cinderella. Cinderella falls just behind Sleeping Beauty with 42% of the characters being female, and it passes the Bechdel Test. However, the type of relationship that it was classified as was “neutral.” This pertains to the fact that the only female characters that Cinderella interacts with are her fairy godmother and her stepmother and step-sisters. While the fairy godmother is a positive character, her only role is to save Cinderella. Cinderella’s only other interactions are then with the antagonists of the story. This creates a neutral relationship because Cinderella’s character is either tormented by the female characters or strictly saved by one. The danger of tests like the Bechdel Test is that they ignore the detail needed to do a proper feminist analysis of the films. Numbers can only show so much and fail to acknowledge the strength of female characters and their story arcs. As discussed in the literature review, Frozen is considered one of best feminist Disney animated films to have been created. Looking at the data from the charts however, Frozen falls in the middle of the pack in the female representation. Compared to a movie like Sleeping Beauty, Frozen excels in the different type of female characters but falls short statistically. In order to get the most out of a feminist analysis, in-depth discussion and review of the characters is a necessity. Many of the criticism that was cited in the literature review are examples of different types of deeper analysis. By combining both types of analysis, this provides the best contextual way of finding solutions and ways for Disney to look ahead in making more positive female represented films.

References

Barnard, L. (2013). Frozen will warm your heart: Review. Toronto Star. Retrieved from https://www. thestar.com/entertainment/movies/2013/11/27/animated_frozen_will_warm_your_heart_movie_ review.html

Bean, K. (2003). Stripping beauty: Disney’s “feminist” seduction. In B. Ayres (Ed.), The emperor’s old groove: Decolonizing Disney’s Magic Kingdom (pp. 53-64). New York, NY: Lang.

Brode, D. (2005). Multiculturalism and the mouse: Race and sex in Disney entertainment. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Cheu, J. (Ed.). (2013). Diversity in Disney films: Critical essays on race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality and disability. Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company.

Ebrahim, H. (2014). Are the “boys” at Pixar afraid of little girls? Journal of Film & Video, 66(3), 43–56. Giroux, H., & Pollock, G. (2010). The mouse that roared: Disney and the end of innocence. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

John, A. (2013, August 21). Beyond the Bechdel Test: Two (new) ways of looking at movies. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2013/08/beyond-bechdel-test-two-new-ways-looking-movies/311930/

Layng, J. M. (2001). The animated woman: The powerless beauty of Disney heroines from Snow White to Jasmine. The American Journal of Semiotics, 17(3), 197–215.

Manley, K. E. B. Disney, the beast, and woman as civilizing force. (2003). In B. Ayres (Ed.), The emperor’s old groove: Decolonizing Disney’s Magic Kingdom (pp. 79-89). New York, NY: Lang.

McClintock, P. (2014, March 30). Box office milestone: “Frozen” becomes no. 1 animated film of all time. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com/entertainment/ movies/2013/11/27/animated_frozen_will_warm_your_heart_movie_review.html

Møllegaard, K. (2014). Critical approaches to comics: Theories and methods. The Journal of American Culture, 37(1), 81.

Monica, P. (2006, January 25). Disney buys Pixar. CNN Money. Retrieved from http://money.cnn .com/2006/01/24/news/companies/disney_pixar_deal/

Sengupta, D. M. (2013, November 29). Movie review: Frozen is both old and newage Disney. Hindustan Times. Retrieved from http://www.hindustantimes.com/hollywood/movie-review-frozen-is-both-old-and-new-age-disney/story-8RnEr2FkUo95lcGnfZnvbK.html

Walt Disney: Art and politics in the American century. (1995). The Journal of American History, 82(1), 84–110.

Literary Analysis Example #4: “Romeo + Juliet = Retrofuturistic Shakespeare” (MLA Style)

Literary Analysis Example #5: “Eliza Bennet’s Hindu Wedding” (MLA Style)

The study, evaluation, and interpretation of a work literature. Such analysis allows us to understand the parts of a literary work to define how they correlate with each other and what influence they make on the work overall.

An open-ended question about a work of human creativity with infinite possible answers that seeks to explore how the pieces of that work function together. This is an example of divergent thinking, as opposed to the more common convergent thinking.

The unique viewpoint, new information, or interesting take on a topic.

A category of artistic composition, as in music or literature, characterized by similarities in form, style, or subject matter.

A situation or detail of a character that complicates the main thread of a plot and presents a challenge, choice, or conflict.

A struggle between opposing forces.

The sequence of events within a narrative.

Word choice; a writer's or speaker's distinctive vocabulary choices and style of expression.

A figure of speech in which a word or phrase is applied to an object or action to which it is not literally applicable.

A figure of speech involving the comparison of one thing with another thing of a different kind, used to make a description more emphatic or vivid (e.g., as brave as a lion, crazy like a fox ).

A comparison of the relationship between two sets of things, typically for the purpose of explanation or clarification.

A beginning section which states the purpose and goals of the following writing, generally followed by the body and conclusion. The introduction typically describes the scope of the document and gives the brief explanation or summary of the document.

The main idea, point, or claim of a written work. Plural: theses.

The majority of an essay in which claims are presented and subsequently proven, described, analyzed, or explained.

A self-contained unit of discourse in writing dealing with a particular point or idea.

The last paragraph in an academic essay that generally summarizes the essay, presents the main idea of the essay, or gives an overall solution to a problem or argument given in the essay.