12

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Use prewriting techniques to get your ideas flowing. (GEO 1, 2; SLO 1)

- Develop your ideas with heuristics. (GEO 1, 2; SLO 1)

- Reflect on your ideas with exploratory writing and extend them in new directions. (GEO 1, 2; SLO 1)

Coming up with new ideas is often the hardest part about writing. You stare at the page or screen, and it stares back. Writers can choose from a wide variety of techniques to help them “invent” their ideas and think about their topics from new perspectives. In this chapter, you will learn about three types of invention strategies that you can use to generate new ideas and explore your topic: Prewriting uses visual and verbal strategies to put your ideas on the screen or a piece of paper, so you can consider them and figure out how you want to approach your topic. Heuristics use time-tested techniques that help you ask good questions about your topic and figure out what kinds of information you will need to support your claims and statements. Exploratory writing uses reflective strategies to help you better understand how you feel about your topic. This kind of open-ended writing helps you turn those thoughts into sentences, paragraphs, and outlines. Some of these invention strategies will work better for you than others. You will also discover that some of them are better than others for particular kinds of papers. Try them all to see which ones are most helpful as you tap into your creativity.

Prewriting

Prewriting helps you put your ideas on the screen or a piece of paper, often in a visual way. Your goal while prewriting is to figure out what you already know about your topic and to start coming up with new ideas that go beyond your current understanding.

Concept Mapping

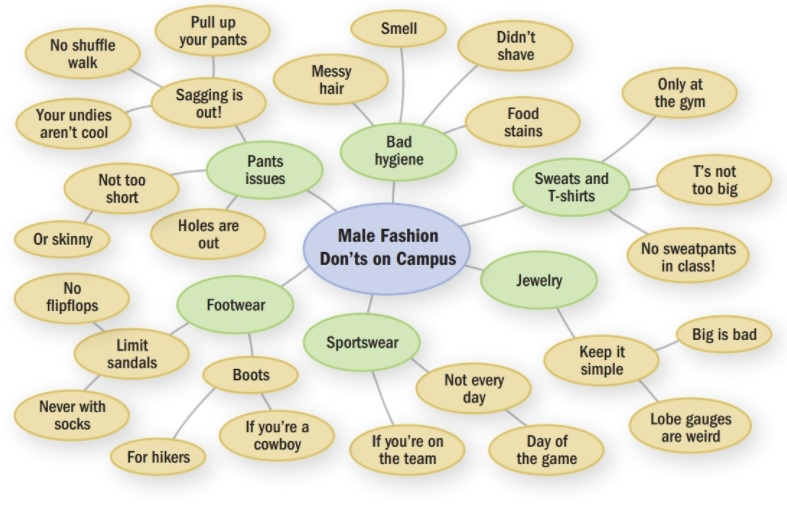

One of the most common prewriting tools is concept mapping. To create a concept map, write your topic in the middle of your screen or a piece of paper (Figure 5.1). Put a circle around it. Then write down as many other ideas as you can about your topic. Circle those ideas and draw lines that connect them with each other.

The magic of concept mapping is that it allows you to start throwing your ideas onto the screen or a blank page without worrying about whether they make sense at the moment. Each new idea in your map will help you come up with other new ideas. Just keep going. Then, when you run out of new ideas, you can work on connecting ideas into larger clusters. For example, Figure 16.1 shows a concept map about the pitfalls of male fashion on a college campus. A student made this concept map for an argument paper. She started out by writing “Male Fashion Don’ts on Campus” in the middle of a sheet of paper. Then she began jotting down anything that came to mind. Eventually, the whole sheet was filled out. She then linked ideas into larger clusters.

With her ideas in front of her, she could then choose the topic and angle that best suited her audience and purpose. The larger clusters became major topics in her argument (e.g., sweats and T-shirts, jewelry, footwear, hygiene, saggy pants, and sports uniforms). Or she could have chosen just one of those clusters (e.g., footwear) and structured her entire argument around that narrower topic. If you like concept mapping, you might try one of the free mapping software packages available online, including Coggle, NovaMind, MindNode, MindMeister, and MindManager, among others.

Freewriting

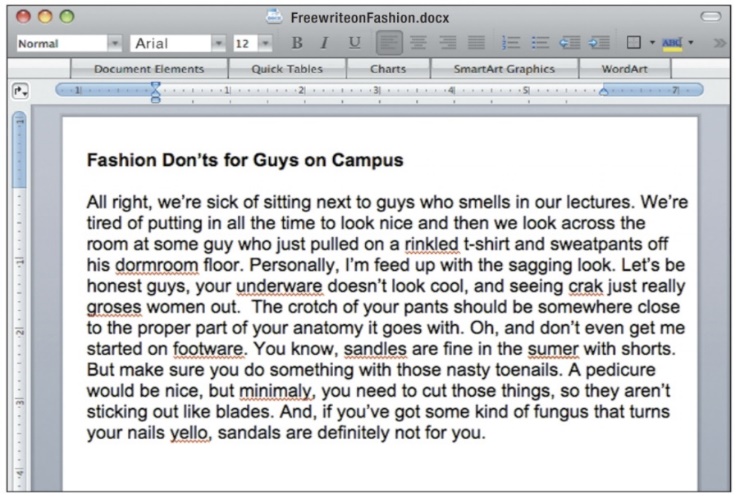

When freewriting, all you need to do is open a page on your computer or pull out a piece of paper. Then write as much as you can for five to ten minutes, typing or jotting down anything that comes into your mind. Don’t stop writing, and don’t worry about putting your ideas into real sentences or paragraphs. If you find yourself running out of words, try finishing phrases like “What I mean is . . .” or “Here’s my point. . . .” When using a computer, try darkening the screen or closing your eyes as you free-write. That way, the words you have already written won’t distract you from writing down new ideas. Plus, a dark screen will help you avoid the temptation to go back and fix any typos and garbled sentences. Figure 5.2 shows an example freewrite. The text has typos and some of the sentences make no sense. That’s fine. The author is just getting her ideas on the screen.

When you are finished freewriting, go through your text, highlighting or under-lining your best ideas. Some people find it helpful to do a second, follow-up freewrite that focuses just on the best ideas.

Brainstorming

To brainstorm about your topic, open a new page on your screen or pull out a piece of paper. Then list everything that comes to mind about your topic. As in freewriting, just keep listing ideas for about five to ten minutes without stopping. Next, choose your best idea and create a second brainstorming list on a separate sheet of paper. Again, list everything that comes to mind about this best idea. Making two lists will help you narrow your topic and deepen your thoughts about it.

Storyboarding

Movie scriptwriters and advertising designers use a technique called storyboarding to help them sketch out their ideas. Storyboarding involves drawing a set of pictures that show the progression of your ideas. Storyboards are especially useful when you are working with genres like memoirs, reports, or proposals, because they help you visualize the “story.”

The easiest way to storyboard about your topic is to fold a regular piece of paper into four, six, or eight panels (Figure 5.3). Then, in each of the panels, draw a scene or a major idea involving your topic. Stick figures are fine.

Storyboarding is similar to turning your ideas into a comic strip. You add panels to your storyboards and cross them out as your ideas evolve. You can also add dialogue into the scenes and put captions underneath each panel to show what is happening. Storyboarding often works best for people who like to think visually in drawings or pictures rather than in words and sentences.

Using Heuristics

You already use heuristics, but the term is probably not familiar to you. A heuristic is a discovery tool that helps you ask insightful questions or follow a specific pattern of thinking. Writers often memorize the heuristics that they find especially useful. Here, we will review some of the most popular heuristics, but many others are available.

The most common heuristic is a tool called the journalist’s questions, or sometimes called the “Five-W and How questions.” Writers for newspapers, magazines, and television use these questions to help them sort out the details of a story.

- Who was involved?

- What happened?

- When did it happen?

- Where did the event happen?

- Why did it happen?

- How did it happen?

Write each of these questions separately on your screen or a piece of paper. Then answer each one in as much detail as you can. Make sure your facts are accurate, so you can reconstruct the story from your notes. If you don’t know the answer to one of these questions, put down a question mark. A question mark signals a place where you might need to do some more research.

When using the Five-W and How questions, you might also find it helpful to ask,

“What has changed recently about my topic?” Paying attention to change will also help you determine your angle on the topic (i.e., your unique perspective or view).

the formulation and organization of ideas preparatory to writing during the first stage of the writing process

A diagram that depicts suggested relationships between concepts.

A prewriting technique in which a person writes continuously for a set period of time without worrying about rhetorical concerns or conventions and mechanics.

An informal way of generating ideas to write about or points to make about your topic.

Drawing a set of pictures that show the progression of your ideas.

A discovery tool that helps you ask insightful questions or follow a specific pattern of thinking.

The unique viewpoint, new information, or interesting take on a topic.