14

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Use the narrative pattern to tell a story. (GEO 2; SLO 1)

- Describe something with the senses or tropes. (GEO 2; SLO 1)

- Define a word or concept. (GEO 2; SLO 1)

- Use classification to put things into categories. (GEO 2; SLO 1)

- Explain what caused something and its effects. (GEO 2; SLO 1)

- Compare and contrast two or more things. (GEO 2; SLO 1)

- Combine rhetorical patterns to make sophisticated arguments. (GEO 2; SLO 1)

Writers use rhetorical patterns to organize ideas and information in ways that readers find easy to follow and understand. Ancient rhetoricians called these patterns topoi, or commonplaces (from the Greek word “place”). Rhetorical patterns are familiar places (topoi) that can help you develop and organize your ideas. A variety of rhetorical patterns are available, but the six most common are:

You may already be familiar with these patterns because they are often used to teach high school students how to write essays, such as cause and effect essays or comparison and contrast essays. Keep in mind, though, that rhetorical patterns are not formulas to follow mechanically. You can alter, bend, and combine these patterns to fit your purpose and the genre you’re using.

Narrative

A narrative describes a sequence of events or tells a story in a way that illustrates a specific point.

Narratives can be woven into almost any genre. In reviews, literary analyses, and rhetorical analyses, narratives can be used to summarize or describe the work you are examining. In proposals and reports, narratives can be used to recreate events and provide historical background on a topic. Some genres, such as memoirs and profiles, often rely on narrative to organize the entire text.

The diagram in Figure 7.1 shows the familiar pattern for a narrative. When telling a story, writers will usually start out by setting the scene and introducing a complication, which presents the characters with a challenging choice or problem. Then the characters evaluate the complication, assessing the nature of the situation. Writers then resolve the complication by describing the outcomes that resulted from the characters’ choices. At the end of the narrative, writers often state the point of the story, or the overall meaning that readers should take away from it.

Consider, for example, the paragraph below, which follows this basic narrative pattern:

Example

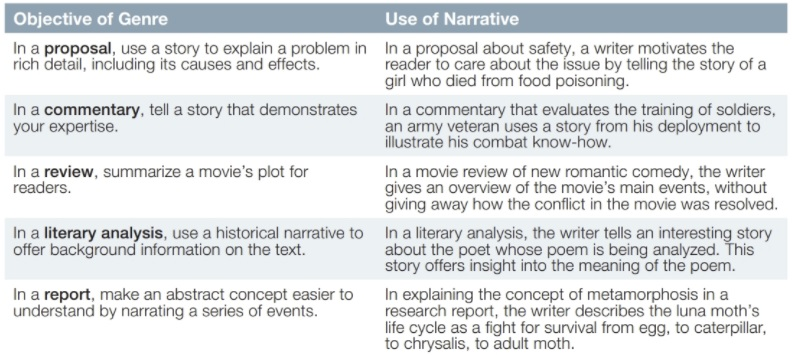

The narrative pattern is probably already familiar to you, even if you didn’t know its name before. This is the same pattern used in television sitcoms, novels, jokes, and just about any story. In nonfiction writing, though, narratives are not “just stories.” They help writers make specific points for their readers. The chart below shows how narrative can be used in a few different genres.

Description

Descriptions often rely on details drawn from the five senses—seeing, hearing, touching, smelling, and tasting. You can also use rhetorical devices, like metaphor, simile, and onomatopoeia, to deepen readers’ experience and understanding.

Describing with the Senses

When you need to describe a person, place, or object, start out by considering your subject from each of the five senses:

- What does it look like? What are its colors, shapes, and sizes? What is your eye drawn toward? What makes your subject visually distinctive?

- What sounds does it make? Are the sounds pleasing, sharp, soothing, irritating, metallic, or erratic? What effect do these sounds have on you and others?

- What does it feel like? Is it rough or smooth, hot or cold, dull or sharp, slimy or firm, wet or dry?

- How does it smell? Does your subject smell fragrant or pungent? Does it have a particular aroma or stench? Does it smell fresh or stale?

- How does it taste? Is your subject spicy, sweet, salty, or sour? Does it taste burnt or spoiled? Which foods taste similar to the thing you are describing?

Describing with Similes, Metaphors, and Onomatopoeia

Some people, places, and objects cannot be fully described using the senses. Here is where tropes like similes, metaphors, and onomatopoeia can be especially helpful.

- Simile. A simile (“X is like Y”; “X is as Y”) helps you describe your subject by making a simple comparison with something else:

- Directing the flow of traffic, police officers move as mechanically and purposefully as a robot on an assembly line.

- Metaphor. A metaphor (“X is Y”) lets you describe your subject in more depth than a simile by directly comparing it to something else.

- A college campus is a small city with neighborhoods, stores, restaurants, entertainment, and even its own transportation system.

- Onomatopoeia. Onomatopoeia uses words that sound like the thing being described.

- The cyclist whooshed by the crowd and then zipped along the road and up the mountain.

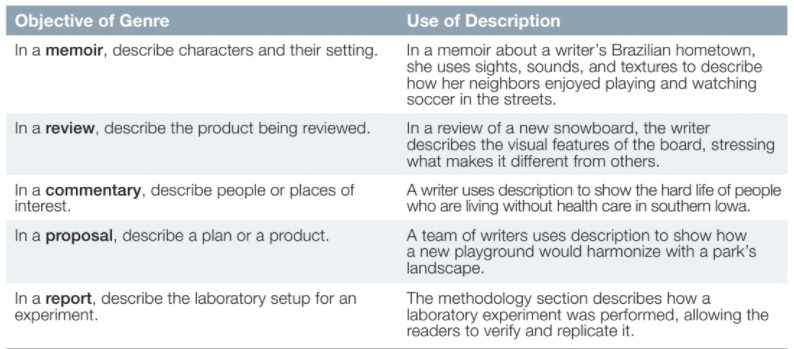

Description is commonly used in all genres, as shown in the chart below. Where possible, look for ways to use combinations of senses and tropes to add a visual element to your texts.

Definition

A definition states the exact meaning of a word or phrase. Definitions explain how a particular term is being used and why it is being used that way. Sentence definitions, like the ones in a dictionary, typically have three parts: the term being defined, the category to which the term belongs, and the distinguishing characteristics that set it apart from other things in its category.

Cholera is a potentially lethal illness that is caused by the bacterium, Vibrio cholerae, with symptoms of vomiting and watery diarrhea.

Category Term Distinguishing characteristics

An extended definition is longer than a sentence definition. An extended definition usually starts with a sentence definition and then continues to define the term further. You can extend a definition with one or more of the following techniques:

- Word origin (etymology). Exploring the historical origin of a word can pro-vide some interesting insights into its meaning.

- According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word escape comes from the Old French word “eschaper,” which literally means “to get out of one’s cape, leave a pursuer with just one’s cape.”

- Examples. Giving examples can put a word’s meaning into context.

- For example, when someone says she “drank the Kool-Aid” for a political party, it means she became a mindless follower of its leaders’ values and ideas.

- Negation. When using negation, you explain something by telling what it is not.

- St. John’s Wort is not a stimulant, and it won’t cure all kinds of depression. Instead, it is a mild sedative.

- Division. You can divide the subject into parts, which are then defined separately.

- There are two kinds of fraternities. The first kind, a “social fraternity,” typically offers a dormitory-like place to live near a campus, as well as a social community. The second kind, an “honorary fraternity,” allows members who share common backgrounds to build networks and support fellow members.

- Similarities and differences. When using similarities and differences, you can compare and contrast the item being defined to other similar items.

- African wild dogs are from the same biological family, Canidae, as domestic dogs, and they are about the same size as a Labrador. Their coats, however, tend to have random patterns of yellow, black, and white. Their bodies look like those of domestic dogs, but their heads look like those of hyenas.

- Analogy. An analogy compares something unfamiliar to something that readers would find familiar.

- Your body’s circulatory system is similar to a modern city. Your arteries and veins are like roads for blood cells to travel on. These roadways contain white blood cells, which act like police officers patrolling for viruses and bacteria.

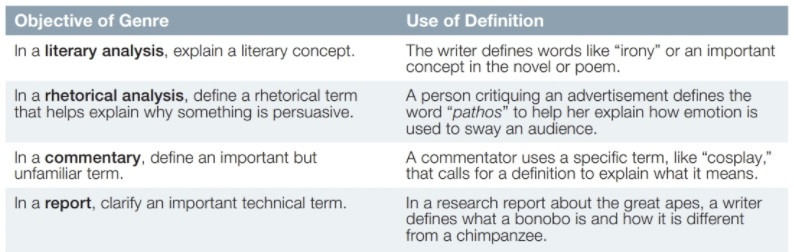

The chart below shows how definitions can be used in a variety of genres.

Classification

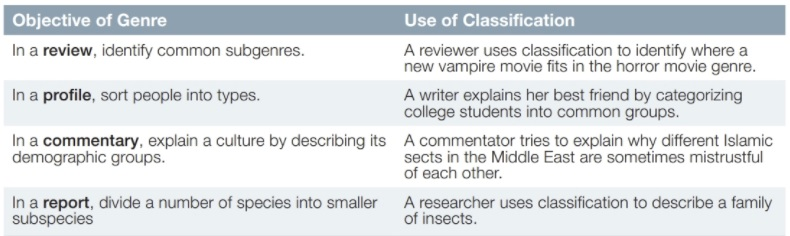

Classification allows you to divide objects and people into groups, so they can be discussed in greater depth. A classification can take up a single paragraph, or it might be used to organize an entire section. Here are a few steps to help you use classification to organize a paragraph or section.

- Step One: List Everything That Fits into the Whole Class List all the items that can be included in a specific class. Brainstorming is a good tool for coming up with this kind of list.

- Step Two: Decide on a Principle of Classification The key to classifying something is to come up with a principle of classification that helps you do the sorting.

- For example, let’s suppose you are classifying all the ways to stop smoking. You would list all the methods you can find. Then you would try to sort them into categories: Lifestyle changes—exercise daily, eat healthy snacks, break routines, distract yourself, set up rewards, keep busy Smoking-like activities—chew gum, drink hot tea, breathe deeply, eat vegetables, eat nuts that need to be shelled Nicotine replacement—nicotine patch, nicotine gum, sprays, inhalers, lozenges, nicotine fading Medical help—acupuncture, hypnosis, antidepressants, support group

- Step Three: Sort into Major and Minor Groups You should be able to sort all the items from your brainstorming list cleanly into the major and minor categories you came up with. In other words, an item that appears in one category should not appear in another. Also, no items on your list should be leftover.

This classification describes a plan to stop smoking and is structured around four major categories:

Example

I really want to quit smoking because it wastes my money and I’m tired of feeling like a social outcast. Plus, someday, smoking is going to kill me if I don’t stop. I have tried to go cold turkey, but that hasn’t worked. The new e-cigarettes are too expensive and just make me want to start smoking again. So, I began searching for other ways to stop. While doing my research, I found that there are four basic paths to stopping smoking:

The first and perhaps easiest path is to make some lifestyle changes. Break any routines that involve smoking, like smoking after meals or going outside for a smoke break. Start exercising daily and set personal rewards for reaching milestones (e.g., dinner out, treat, movie). Mostly, it’s important to keep yourself busy. And, if needed, keeping pictures of charcoal lungs around is a good reminder of what happens to people who don’t give up smoking.

For many of us, the physical aspects of smoking are important, especially doing something with the hands and mouth. Some people keep a bowl of peanuts around in the shells, so they have something to do with their hands. Drinking hot tea or breathing deeply can replicate the warmth and sensation of smoking on the throat and lungs. Healthy snacks, like carrots, pretzels, or chewing gum, will keep the mouth busy.

Let’s be honest—smokers want the nicotine. A variety of products, like nicotine gum, patches, sprays, and lozenges can hold down those cravings. Also, nicotine fading is a good way to use weaker and weaker cigarettes to step down the desire for nicotine.

Medical help is also available. Here on campus, the Student Health Center offers counseling and support groups to help people stop. Meanwhile, some people have had success with hypnosis and acupuncture.

My hope is that a combination of these methods will help me quit this habit. This time I’m going to succeed.

The author of this classification has found a good way to sort out all the possible ways to stop smoking. By categorizing them, she can now decide which ones will work best for her.

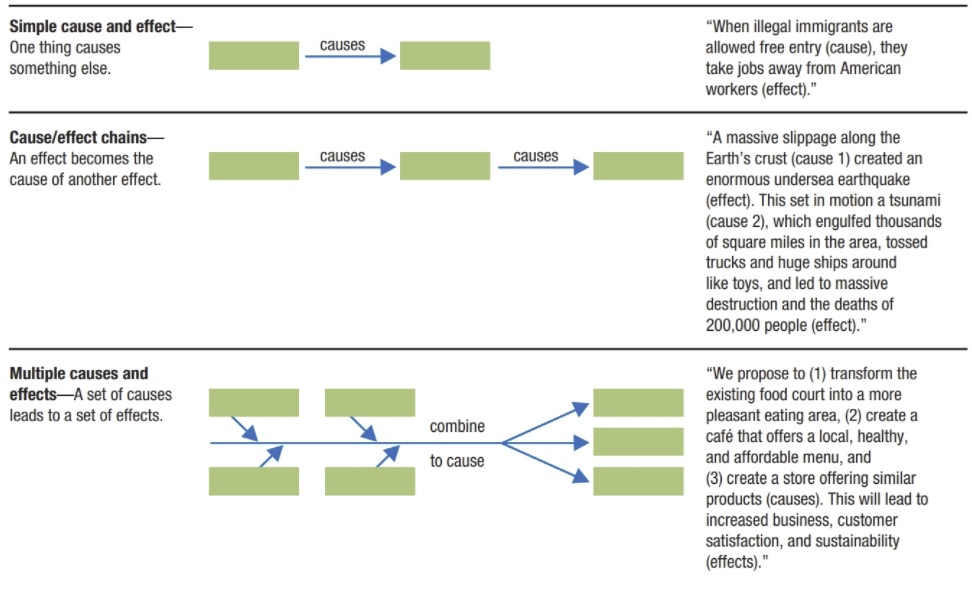

Cause and Effect

Exploring causes and effects is a natural way to discuss many topics. Identifying causes is the best way to explain why something happened. Exploring the effects is a good way to describe what happened afterward. When explaining causes and effects, identify both causes and effects and then explain how and why specific causes led to those effects.

Even when describing a complex cause and effect scenario, you should try to present your analysis as clearly as possible. Often, the clearest analysis will resemble a narrative pattern, as in this analysis of tornado formation:

Example

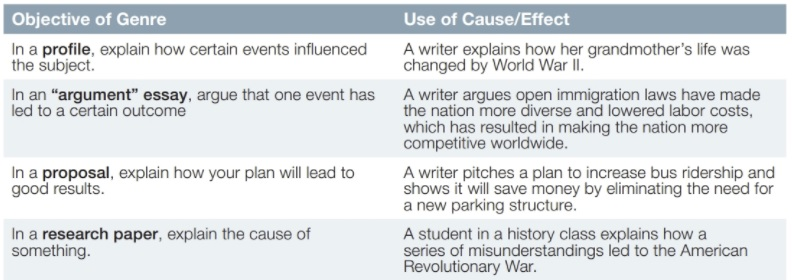

The chart below shows how different kinds of cause and effect analyses can be used in a variety of genres.

Comparison and Contrast

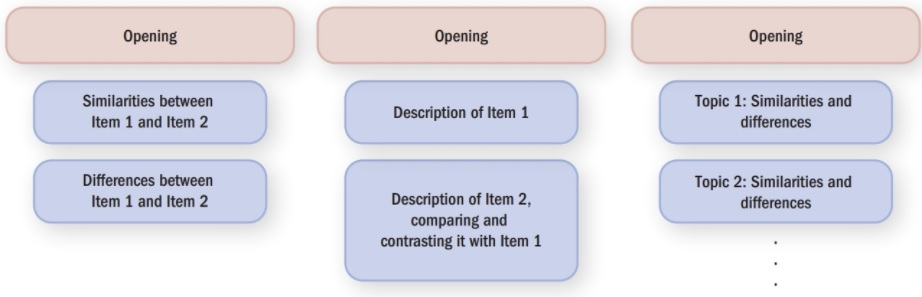

Comparisonandcontrast allow you to explore the similarities and differences between two or more people, organizations, objects, places, or ideas. When comparing and contrasting, you should first list all the common characteristics that the two items share. Afterward, list all the distinguishing characteristics that make them different.

You can then show how these two things are similar to and different from each other. Figure 7.3 shows three patterns that could be used to organize the information in your list. The first two sentences of the paragraph below describe common characteristics, followed by several sentences describing distinguishing characteristics:

Example

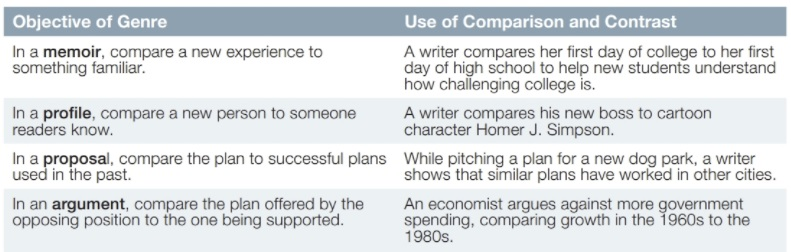

Comparison and contrast is a useful way to describe something by comparing it to something else. It can also be used to show how two or more things measure up against each other. The chart below describes how comparison and contrast can be used in a variety of genres.

Common techniques to present organized ideas and information for the audience to better understand.

Patterns; from the Greek word for "commonplace."

A spoken or written account of connected events; a story.

A pattern of narrative development that aims to make vivid a place, object, character, or group.

A statement of the exact meaning of a word or idea.

The action or process of classifying something according to shared qualities or characteristics.

Influence by which one event, process or state contributes to the production of another event, process or state where the cause is partly responsible for the effect, and the effect is partly dependent on the cause.

The act of evaluating two or more things by determining the relevant, comparable characteristics of each thing, and then determining which characteristics of each are similar to the other.

The act of evaluating two or more things by determining the relevant, contrasting characteristics of each thing, and then determining which characteristics of each are different to the other.

A category of artistic composition, as in music or literature, characterized by similarities in form, style, or subject matter.

A situation or detail of a character that complicates the main thread of a plot and presents a challenge, choice, or conflict.

A figure of speech involving the comparison of one thing with another thing of a different kind, used to make a description more emphatic or vivid (e.g., as brave as a lion, crazy like a fox ).

A figure of speech in which a word or phrase is applied to an object or action to which it is not literally applicable.

The formation of a word from a sound associated with what is named (e.g. cuckoo, sizzle ).

A longer definition that spans one or more sentences.

The study of the origin of words and the way in which their meanings have changed throughout history.

The action or logical operation of negating or making negative.

A comparison of the relationship between two sets of things, typically for the purpose of explanation or clarification.