An overview of the portfolio & how to create one.

Now that we have learned about inflation and assets, we may begin to develop a plan and strategy. For many people, the goal is to preserve and grow their wealth by saving, but we will be focusing on investing. We want to be preserving and growing our wealth through the asset ownership process of investing. Let’s go.

Perhaps you’ve heard the term portfolio used in the news or in articles. But what does that really mean? A portfolio is simply a collection of assets; one could have a stock portfolio, a bond portfolio, a real estate portfolio, a contemporary art portfolio, and so on. Most American portfolios contain a mix of some or all of the assets we have discussed – this is what makes the portfolio so essential and powerful. It protects us from inflation and provides for future dreams and expenses. Some people have large, varied portfolios; others have their assets concentrated in one or two key assets. The portfolio is as unique as you are, and there are a million different ways to craft it. Nothing is set in stone; portfolios can change and morph as you move through life acquiring or selling assets. There are many schools of thought and businesses dedicated to helping people construct the correct portfolio, and while that is an interesting topic, it is far too vast for this book. We will focus on the basics.

For most Americans, the single-family residence is the largest item in their portfolio. For middle-class families, it is estimated that home equity, or the amount of the mortgage you have paid off, represents 50-70% of net worth.[1] Therefore in most cases, more than 50% of the family’s entire assets are concentrated in their home. Not only is the house an important shelter for living, it is also the most important and biggest asset your family owns. From an investing perspective, owning a home is no joke.

We also know that there is a huge difference between the net worth of homeowners and renters. On average, the person or family who owns a home has approximately 40 times the net worth of someone who rents.[2] Why is that the case? The basic answer is that money spent on rent isn’t going to any asset – it is paid and then lost forever. In comparison, the mortgage payment amount is added to the total you have paid the bank back towards the home. This is known as home equity.

Take an example of a house worth one million dollars. One homeowner has paid off their entire mortgage, owns the property outright, and therefore has one million dollars in home equity. Another homeowner made a 20% down payment of $200,000 and has an outstanding mortgage balance of $800,000. They are said to have $200,000 in home equity. Later, if they had paid half of their outstanding loan, they would have bought back an additional $400,000 of home value, bringing the equity to $600,000. Think of mortgage payments as buying back small pieces of your home from the bank over a long period of time. As we can see, this greatly trumps renting, where the money is simply lost to the landlord. The evidence is clear that the system greatly rewards the asset owner and investor.

![]()

So if homeownership takes up 50% of net worth, where does the rest of the 50% of Americans’ portfolios go? This 50% is made up of a variety of things. The biggest is undoubtedly stocks, which just recently were estimated to make up 42% of household wealth from data compiled by the Federal Reserve.[3] Much of this stock wealth comes in the form of retirement accounts, with 401Ks being a primary indicator and measure of household wealth. The 401K is the primary retirement savings vehicle for most Americans. It functions very similarly to other brokerage and investment accounts. Retirement is the most expensive venture in anyone’s life, and the 401K is the chosen vehicle for enjoying the golden years. The 401K is named after a section in the Revenue act of 1978, a broad tax bill that was aimed at incentivizing retirement savings and lowering investment taxes for the middle class. As part of this tax code change, employees of large firms were now allowed to contribute to their retirement savings directly out of their paychecks before taxes were taken out, letting them receive a tax deduction for the amounts they contributed.

This was also greatly beneficial for employers, who, up to that point, hadn’t figured out a way around the traditional pension-style retirement plan. Pensions are guaranteed income for employees paid by their employers upon retirement. Pensions are risky and expensive for the companies providing them. Regardless of how business is doing, they must guarantee pension to their employees. The 401K rule allowed employees to put direct portions of their salaries into retirement savings and receive tax benefits for doing so. This shifted the risk of funding retirements away from the employers and onto the employees, as individuals are able to choose what investments go into their 401Ks. However, in an effort to encourage retirement savings, employers often match the contributions made by their employees, incentivizing them to stay with the company and save for retirement.

The 401K plan has taken over the retirement savings and planning industry. Nearly every large employer offers a plan, and match contributions can be quite generous – sometimes exceeding 10%. This means that for every contribution of $100 that the employee makes, the company will match up to 10%, or in this case $10, for the employee. This is also a very solid immediate 10% return, which easily beats our inflation target of 3%, with zero risk involved. Based on the company’s policy and some federal laws, these funds for your retirement must be made available to you within 5 years of your start date, regardless of whether or not you stay with the company. If you have a new job, with a new 401k, you can do a transfer or rollover of the assets.

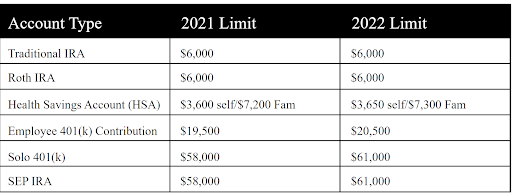

401Ks act as a brokerage account, and within this account, the owner can buy many of the assets we have mentioned so far – stocks, bonds, real estate funds, cash, and so on. 401Ks also fall into the larger family of retirement accounts, which include IRAs (individual retirement accounts), Defined Benefit plans (similar to pensions), and SEP IRAs/Solo 401Ks (Simplified Employee Pensions). The major difference between the 401K (with the exception of the Solo 401K) and these other plans is the aspect of employer sponsorship. For example, a traditional IRA is a savings or investment account that people can open with a bank or brokerage. This account functions the same as a 401K but is 100% owner funded. The same tax deduction benefits also apply. Another type of IRA is the Roth. The Roth IRA does not allow for tax deductions in the year contributions are made. However, the money (and all investment gains) may be withdrawn tax-free. For many young people, a Roth IRA is the best tool to start saving for retirement. It is recommended by nearly all financial professionals. Finally, the SEP or Simplified Employee Pension IRA/Solo 401K is specific to self-employed workers, business owners, or single-owner businesses such as freelancers, consultants, lawyers, architects, and so on. The SEP/Solo 401K allows them to save for retirement in larger amounts than the other plans, as they don’t have the benefit of a corporate sponsor. The chart below shows the associated limits of contribution for each account type per year.

*It can be noted that the Health Savings Account (HSA) is on here, yet as this serves a different purpose in terms of asset ownership/investing we won’t go into an explanation of it.

The remaining 10% or so of average wealth falls into savings and checking accounts. The figure used most widely to determine the savings rate is the Federal Reserve’s personal savings rate figure. The average long-run value for this sits between 6% and 7% and increases exponentially by class (higher income earners tend to save more, while people making less save less.[4] We can safely assume that after the personal savings rate, the remainder of household net worth falls into checking accounts for quick access and daily expenses.

![]()

You may have some of these assets already, and I would guess most are in the form of checking or savings accounts. So let’s do an exercise to set up a financial foundation before we move into asset ownership. I want you to spend a few minutes writing down all of the things you spend money on. Then, next to each item, write down their monthly cost. Finally, I want you to add up all of those numbers and arrive at a grand total. Circle that number. That is your total expenses for any given month. This is all the money you have going out the door for the things you want and need in order to be happy and live well.

The next step is to calculate how much you take in monthly, known as your income. This could be a paycheck from work, money from your side business, or allowance or gifts from your family. If you aren’t currently working, this will be harder to estimate. Do your best, and remember this technique when you begin to work. Lastly, take the total of your expenses and multiply it by three. This is an estimate of your emergency fund, and should always be readily available in your savings account. If something were to happen, like injury or sickness, an emergency fund is critical. It protects you in the event that you are unable to work and gives you ample time to find solutions.

Now take a look at the balances of your checking and savings accounts. Is there enough for three months of expenses in your savings? Is there more? How do you feel about the money in there? The practical rule states that you should not own any assets until you have a checking account with which to pay your bills and a savings account with three months of living expenses (the emergency fund). Take a quick thought break. If you were an asset owner, would you want to sell your assets to have enough money to survive? Would that be a hard choice? By implementing a concrete rule for saving, we can protect ourselves from these situations. Before we invest or purchase assets, it is of the utmost importance that we are saving to reach the total for our emergency fund.

Now that we understand assets and the three-month rule we must meet before starting to invest, we are faced with our biggest question yet: Which assets should you purchase to fill your portfolio? There is no easy answer to this question. Your portfolio will be as unique as you are, much of it depending on your age, your financial situation, tolerance for risk, and so on. I may not be able to tell you how to build the perfect portfolio (if that even exists), but I can provide you with some widely accepted strategies and methods used by asset managers. Let’s carry on.

- Jenny Schuetz, “Rethinking Homeownership Incentives to Improve Household Financial Security and Shrink the Racial Wealth Gap,” Brookings Blueprints for American Renewal & Prosperity (Brookings, December 9, 2020), https://www.brookings.edu/research/rethinking-homeownership-incentives-to-improve-household-financial-security-and-shrink-the-racial-wealth-gap/. ↵

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Federal Reserve Board - Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF),” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Federal Reserve, 2019), https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/scfindex.htm. ↵

- Jeff Cox, “In Today’s Environment, the Notion That the Stock Market Isn’t the Economy Doesn’t Hold up Anymore,” Economy (CNBC, May 9, 2022), https://www.cnbc.com/2022/05/09/the-notion-that-the-stock-market-isnt-the-economy-just-doesnt-hold-up-anymore.html. ↵

- Financial Samurai, “The Average Saving Rate by Income (Wealth Class),” Financial Samurai, April 7, 2020, https://www.financialsamurai.com/the-average-savings-rates-by-income-wealth-class/. ↵

The amount of your house you own as opposed to owe on your mortgage, home equity represents your vested interest in a residential real estate property.

The 401K is the primary type of retirement savings for Americans. 401K plans are sponsored by your employer and allow you to automatically contribute a fixed dollar or percentage amount of your income into a retirement account. Many employers, in an effort to offer benefits to employees, will also contribute to this retirement account on your behalf as well.

Out of your disposable or discretionary income you may choose to save some and/or spend some. Your savings rate is the percentage of your left over money after all your non-discretionary bills have been paid that you are able to save.

Your expenses are the items you spend money on over a given period of time, most commonly monthly or annually. Expenses include discretionary items such as meals out or new toys and non-discretionary items like rent, food, gas and utilities.

Your income is how much money you take in over a certain period of time, most commonly monthly or annually. Income can come from many sources such as wages, salary, investment/rental income, social security or insurance/retirement benefits.

Something everyone should have before beginning to invest, the Emergency Fund is recommended to be 3-6 months of active living expenses.