12.6 Analyzing Film: Evaluation and Interpretation

Film is useful to study in any Composition course—not only because film shapes our lives but also because the medium is grounded in the relationship between the filmmakers and the audience. Film is inherently rhetorical in that the success of a film is dependent upon the ability to persuade. In any experience of watching a film, we have a great example of the rhetorical triangle in practice.

Just like a book or painting, Film has its own specific formalist elements and principles. The elements of a film include: screenplay, set design, acting, directing, costumes, cinematography, editing, lighting, music, sound, special effects, and so on.

Two Strategies for Taking Notes on Movies

We all watch movies and shows; it is one of our most popular pastimes. However, watching a film in order to analyze it is different from watching a film in order to be entertained. To that end, it is helpful to have specific strategies for taking notes so that you stay in analytical mode while you watch the film.

Strategy One: Questions focused on Film Elements

One strategy for taking notes on a film is to focus on one of more of the film’s formalist elements and ask a specific set of questions about that element. The questions below are inspired by and partly adapted from William H. Phillips, Film: An Introduction (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1999).

- Screenplay: Character: Who is the protagonist? What do they want? Are they successful? If so, at what point in the story?

- Screenplay: Dialogue: How is dialogue used to create unique characters? Which lines (in general) are particularly interesting (funny, surprising, sad, etc.)? Which lines, if any, are repeated throughout the film?

- Screenplay: Structure: As you are watching the film, jot down those moments that surprise you, those moments that seem predictable, and those moments in which you think you’ve got it figured out.

- Set Design: What do the settings add to the film? Are the settings true-to-life or imaginary? What shapes are being used – in which scenes are the set pieces and the props curvy and in which scenes are the set pieces and the props angular and linear? which characters are costumed in cool colors, and which are costumed in warm colors?

- Acting (focused on one specific character): What actions are especially revealing about the character? That is to say, how is actor using their body (gestures, gait, posture, facial expressions (head/eye/eyebrow/mouth movement), and voice (accent, timber, pace, delivery) to create the character?

- Costumes: Focusing on the five suspects, which characters are costumed in cool colors (blue, tan, green, gray) and which are costumed in warm colors (red, black)? What is the cloth pattern for each character (e.g. is the material solid or is it patterned in some way—paisley, striped, lamé, etc.)? Do these colors and these patterns change throughout the film for any of the characters, and, if so, how? How, if at all, is the styling of the clothing unique to each character?

- Lighting: Where is lighting used to create a particular mood? Does the film use cool or warm colors? Is color used in a symbolic way? Where is the lighting white and where does the camera seem to have a “filter” over the lens, producing a red, blue, or yellow tone?

- Cinematography: Jot down a list of the images that seem important or are repeated. From the list select the most important ones; then explain why they are significant.

- Cinematography: What camera distances are used? How are the subjects arranged within the frame? Are the bunched up or spread apart? Are they in the center or off to a side? Are they in the background or foreground? Are the subjects shot from above or below?

- Cinematography/Editing: Pace: In which scenes does the camera tend to move and in which scenes does it tend to remain stationary? Are there any particular types of shots that you notice being used (e.g. tracking shot, pan shot) to create this sense of pace? Is the film’s editing characterized by fast cutting or slow cutting?

- Editing: Transitions: Pay attention to how the film transitions from one scene to the next and/or from one shot (visual moment) to the next? How has the editor constructed these transitions and to what effect? (for instance, are there moments in which the visual from the former scene remains on screen but is overlapped by the sound from the next scene? or, are there moments in which there is no smooth transition but rather there is an abrupt end to the first scene before beginning the next scene – the screen may even go totally dark and/or the music/sound may go totally silent?)

- Music: Where and why is music used? On what individual instruments (as far as you can tell) does the music seem to be played? Are there musical themes that are repeated, and, if so, what do you notice about these moments? Are there any moments of silence in the film, and, if so, what is going on?

- Sound effects: Jot down a list of the sounds that seem important or are repeated. From the list select the most important ones; then explain why they are significant.

Strategy Two: Treatment + Analysis

A second note-strategy for analyzing a film is “Treatment + Analysis.” A film treatment is written in the development phase of a film project, and it outlines the major scenes of a film. To adapt this practice into a note-taking technique, divide your page in half. On the left side, recreate the treatment with a keyword summary of the scene and write down the time markers for that scene (if you are watching on a device or player and able to see the time markers); on the right side of the page, write your analytical notes. Try to make at least two observations per scene. Do you not stop the film; key words are preferred at this point. After each scene, add a line to separate, and begin taking notes on the next scene.

Write down facts rather than your impressions. You want to use this note-taking strategy to collect evidence so that you can develop an argument rather than just state your opinion. The kind of evidence that will be useful in your essay will be details, specifics, and quotations. You won’t be able to turn your impressions and opinions into an essay unless you have collected evidence to support your observations.

When implementing this strategy, you should aim to collect between 4-12 pages of notes for a two-hour film.

Two Examples of Notetaking: Weak vs. Strong

Here are two observations from a screen of The Great Gatsby (2013), to illustrate the differences between a weak and strong note.

Weak Example

Scene: Tom stops at Wilson’s shop

Analysis: Myrtle comes across as trampy

Strong Example

Scene: Tom stops at Wilson’s shop

Analysis: Myrtle – camera focuses on legs and cleavage before we see her face. Costume — Red, tight clothes, red lipstick, fishnet

Weak Example

Scene: Gatsby and Daisy reunite

Analysis: Gatsby feels nervous.

Strong Example

Scene: Gatsby and Daisy reunite

Analysis: Gatsby paces room, knocks over clock, mouth open, stares at Daisy, stutters “g-g-good to see you”

Two Approaches to Writing about Film: Evaluation and Interpretation

Now that we have considered various strategies for note-taking when analyzing movies, let’s turn our attention to essay writing. When it comes to writing about Film, two of the most frequently assigned types of essays are evaluation and interpretation.

Preparing for a Film Evaluation Essay

Writing a film evaluation sounds deceptively easy. After all, evaluating movies and shows is something we do frequently. When your partner asks if you want to watch Emily in Paris, and you grumble back, “No way; that show is awful,” you are making an evaluation of sorts. When you catch the babysitter letting your adolescent son watch Scream, and you say, “I am not okay with my little boy watching that horror film,” you are making an evaluation of sorts. When you find yourself saying, “I can’t believe Belfast didn’t win Best Picture at the Oscars this year—that film has such amazing acting,” you are making an evaluation of sorts. However, writing a thorough evaluation essay about a movie is much more involved than giving a simple thumbs-up or thumbs-down. An evaluation is not simply your opinion.

An evaluation paper is grounded in an argument, not an opinion. A good film evaluation essay has a clear thesis statement that argues for the strengths and weaknesses of the film. A good film evaluation essay contains evaluative claims that are measured using specific criteria and supported with viable evidence.

Let’s imagine that you have been given the assignment of choosing three formalist elements of a film and writing an essay based on your evaluation of those elements. The structure of your essay should be: a claim for each of the elements, criteria to base each claim on, and evidence to support each claim.

The most important attribute of the evaluative argument is the criteria. The criteria define what “good” or “bad” means. Without specific criteria to use to measure—for instance, the cinematography, set design, and acting—your film essay will only be based upon opinion rather than an argument. To prepare to write your film evaluation essay, draft your three evaluative statements.

- The _____ is good/bad because ________________________.

- The _____ is good/bad because ________________________.

- The _____ is good/bad because ________________________.

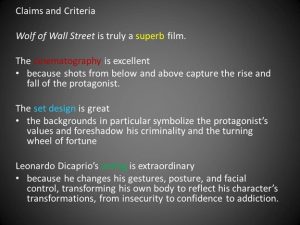

For an example of claims that have clearly stated criteria, see the sample outline for an evaluation essay on The Wolf of Wall Street.

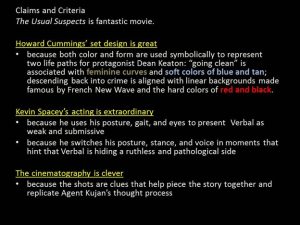

For an additional example of claims that have clearly stated criteria, here is a sample outline for an evaluation essay on The Usual Suspects.

The point of film evaluation is to look more closely than usual at the components of your movie, to isolate what you like about the movie, and to develop your ability to analyze those components, on your own.

For a supplemental guide to formalist analysis of film, one OER is Film Appreciation by Yelizaveta Moss and Candice Wilson. Their chapters on mise-en-scène and cinematography are particularly useful.

Keep in mind, though, that a good writer doesn’t go to outside sources for any components of their essay that they are capable of writing. If you think that you have chosen an element that you lack the experience to analyze, then choose another element. Don’t understand special effects? Switch to costumes. Aren’t sure how to analyze directing? Change your focus to acting. If your assignment calls for a summary of the film, you should be the person who writes that summary. If your assignment calls for descriptions of the scenes, you should be the person who writes those descriptions.

Writing a Film Interpretation Essay

Evaluation involves making an analytical argument about a film’s quality, or lack thereof. Interpretation, on the other hand, is focused on a film’s meaning. In the sample outline for the essay on The Usual Suspects offered above, one of the claims is based on interpretive criteria—specifically, the writer says that in designing the set, Howard Cummings used color and pattern symbolically. Focusing on the meaning of a formalist element is an act of interpretation. In the example mentioned, though, interpretation is used as a criteria for making an evaluation—the writer argues that the set design is good because it holds up to interpretation—rather than having interpretation be the focus of the argument.

This textbook provides you with several chapters on interpreting multiple types of literature, including plays, novels, poetry, and creative non-fiction. Films, too, are literary works that are subject to interpretation.

Excerpts from a Book-to-Film Interpretation Essay

The following sections are excerpted from an essay that compares the theme of suffocation in The Great Gatsby novel and film. The author of the essay takes a Feminist or Gender Studies approach and focuses on two specific formalist elements: descriptive passages in the novel and cinematography in the film.

Example

[…..]

In The Great Gatsby, the antagonist, Tom Buchanan, is associated with death in the sense that he takes the life out of the women who love him. F. Scott Fitzgerald achieves this effect in the novel largely through descriptions of the scenes in Tom’s house whereas Baz Luhrmann achieves this effect in the film via the visual motif of the pearls.

Fitzgerald equates Tom with suffocation from Tom Buchanan’s first scene. Nick Carraway, as narrator, relates his impression when he enters the Buchanans’ house by saying:

The only completely stationary object in the room was an enormous couch on which two young women were buoyed up as though upon an anchored balloon. They were both in white, and their dresses were rippling and fluttering as if they had just been blown back in after a short flight around the house. (8) [1]

The words that Fitzgerald uses here invoke two senses. The first is of levity—the women are lifted “up” by the wind like they are in a “balloon” and have taken “flight.” The second is of movement—the dresses are “rippling” and “fluttering,” and they women are being “blown” and “buoyed.” At this point in the scene, the tone is an upbeat, lively one. That tone changes, however, once Tom enters the room. Fitzgerald writes, “Then there was a boom as Tom Buchanan shut the rear windows and the caught wind died out about the room, and the curtains and the rugs and the two young women ballooned slowly to the floor” (8). Tom’s presence stops the “wind.” Fitzgerald’s choice of words—“died out”—suggests that this is a kind of violence—Tom kills the air. The word “boom” invokes a weapon, such as a gunshot or the roar of a cannon. At the same time, Tom also seems to kill the happiness and good spirits that were circulating throughout the room. Not only are the windows “shut,” and the air stopped, but Daisy and Jordan are brought down “to the floor” because of Tom.

In his 2012 film adaptation of Fitzgerald’s novel, Baz Luhrmann offers the same reading of Tom Buchanan’s character, representing him as the character who brings death to the women he purports to love, and even replicating Fitzgerald’s idea that Tom metaphorically suffocates the women in his life. However, Luhrmann achieves this effect in the film not through description or narration of the scenes in the Buchanan mansion but, rather, via cinematography—specifically in the repeated visual motif of pearls.

In fact, in Luhrmann’s portrayal of the aforementioned scene, rather than stopping the movement of Daisy and Jordan, Tom is the character in motion (fig. 1).

The scene opens with a rush of movement as Tom gallops up the lawn on his polo pony, the camera chasing after him in one quick tracking shot, as if trying to catch up to his speed. Once inside his home, as in Fitzgerald’s description in the book, Tom is the character who goes to close the doors. However, in Luhrmann’s film it is not Tom’s action or noise that causes the wind to die out in the room (figs. 2-3). Instead, it is the name of another problematic male character: Gatsby. At the sound of Gatsby’s name—repeated by Daisy—the curtains deflate and Daisy’s spirits droop (figs. 4-5).

It is in the visual motif of pearl necklaces that Luhrmann centers his representation of Tom as an agent of death. Two women receive pearls from Tom in the film, and Luhrmann repeats the same symbolism in both scenes.

In the first instance, Jordan narrates a series of flashbacks that function as exposition detailing Daisy’s mixed feelings leading up to her wedding day. Jordan tells Nick that Tom “gave [Daisy] a string of pearls worth $350,000.” This last line is taken directly from the novel (59). However, where Fitzgerald simply marks the necklace as a sign of Tom’s incredible wealth, Luhrmann alters Jordan’s narrative and associates the necklace with criminal levels of violence. “Tom Buchanan of Chicago swept in and stole [Daisy] away,” Jordan says as the camera shows Tom grabbing on to the back of the pearl neck that sits on Daisy’s neck—as if seizing the power to choke the life out of Daisy and control any future movement (figs. 6-7).

Fitzgerald records Daisy’s reluctance, on her wedding day, to go through with the ceremony and he mentions that somehow the pearl necklace has ended up in the trash: “[s]he groped around in a waste-basket she had with her on the bed and pulled out the string of pearls” (57). However, Fitzgerald never depicts the moment that Daisy takes off the necklace. Luhrmann, by contrast, revels in the moment—revising the scene so that rather than throw away the necklack intact, Daisy actually rips the chains off of her neck, sending the pearls flying everywhere as she screams, “Tell them Daisy’s changed her mind!” The film captures this iconic action in slow motion (figs. 8-10).

In the novel, Jordan never details what happens to get Daisy to put the pearl necklace back on. Jordan only remarks that “half an hour later, when we walked out of the room, the pearls were around [Daisy’s] neck and the incident was over” (61). Luhrmann, however, invents and dramatizes the scenario, depicting Daisy’s mother grabbing her sewing needle, stitching the pearls back together into a chain again, and insisting that Jordan never tell anyone about Daisy’s reluctance to marry Tom (fig. 11). In the next scene, Luhrmann shows the first string of the pearl necklace tightly around Daisy’s neck—like a hangman’s noose or a slave’s chain—as Jordan continues the narration: “Daisy Fay married Tom Buchanan” (fig. 12).

In the film, the second woman who receives expensive pearl chains from Tom is his mistress, Myrtle Wilson. Importantly, this is not depicted at all in the book. Fitzgerald shows Tom buying Myrtle a dog and financing her apartment in the city so that he has a place where he can sleep with her (21), but he never buys Myrtle a pearl necklace. In Luhrmann’s film, not only does Tom buy a pearl necklace for Myrtle; the necklace also holds the same symbolism.

Myrtle wears the necklace in her death scene as her jealous husband grabs her by the back of the chain, accused her of infidelity, and smashes her head against the window (fig. 13). Myrtle tries to escape, and, seeing Tom’s car, she runs toward it—her strings of pearls in movement with her (fig. 14). The camera captures the action in slow motion as her body is catapulted into the air before she lands on the pavement. The pearls fly everywhere, a visual motif that replicates the earlier portrayal of Daisy’s pearls (fig.15-16).

[…..].

As you can see from reading the excerpts from the essay on The Great Gatsby, the goal in writing an interpretive essay is to apply one or more theoretical methodologies, or critical lenses, to your analysis of the film. Even if your instructor does not assign a film interpretation essay per se, writing about film can be a good way to practice your skills of literary interpretation, by starting with movies—a medium that is familiar and fun.

Notes

[1] Page numbers are taken from F. Scott. Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, 1925 (New York: Scribner, 2004).

Continue Reading: 12.7 Analyzing Graphic Novels