7.4 Revise Your Thesis

It is a myth that writers first come up with a thesis and then write their essays. The reality is that writers use issue-based questions to read, learn, and develop a thesis throughout the process of writing. Through revising and discussing their ideas, writers hone their thesis, making sure that it threads through every paragraph of the final draft. The position writers ultimately take in writing—their thesis—comes at the end of the writing process, after not one draft but many. Therefore, it is okay even if you cannot think out one clear thesis in the first place. As we practiced earlier, your thesis will evolve throughout writing process. Let a thesis keep changing and developing! Well, at least until the due date.

As you write your essay, it’s possible that you’ll create new ideas for supporting points or find and integrate new evidence to support your main claim. It’s even possible that, during the writing, researching, and reading processes, you find convincing evidence that makes you change your original position on the topic. Whatever the case, it is likely that your original vision for your essay will change to some degree as you write.

If your essay’s body contents begin to change, it might be necessary to revise your essay’s thesis so that it accurately and adequately reflects the new or changed content. Consider the following practices as you write your essay:

- Pause after writing each new paragraph.

- Read this new paragraph, then read your essay’s thesis. Ask yourself the following questions:

- Does the thesis reflect the inclusion of this paragraph?

- Does this paragraph make sense underneath your current thesis?

- Would a reader be surprised to read this paragraph?

If you find that this new paragraph doesn’t quite match the content of your current thesis, then it might be time to revise your thesis. Revision at this stage might include:

- Expanding the thesis to include more detail about new supporting points.

- Removing details from the thesis that are not relevant to the direction your essay is taking.

- Changing the claim of the thesis so that it matches the direction your essay is taking.

If you take the time to review your thesis after each new paragraph, you can improve your essay’s thesis and the coherency of its structure.

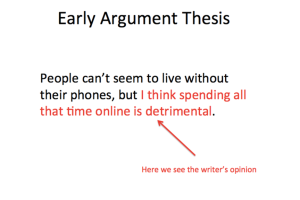

Let’s say you have to create a thesis on a topic like a smart phone. Maybe you’ve already read some essays or secondary sources on this subject, and maybe you haven’t, but you want to start drafting your thesis with a claim about your topic. Bring to your claim what you know and what you think about it:

Good start! This thesis certainly makes a claim because it demonstrates some knowledge or authority, and because it includes two sides to the issue. Can we make it better? Remember, you have to be able to write a paper in support of your thesis, so the more detailed, concrete, and developed your thesis is, the better. Here are tips:

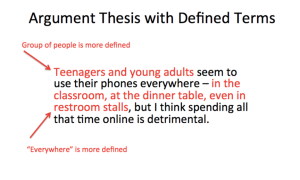

- Define your terms. What do you mean by people? Can that word be replaced with young people, or teenagers and young adults? If you replaced people with these more specific terms, you could write your paper with more specificity and precision. You also might define “can’t seem to live without,” which sounds good initially but is too general without explanation, with something more exact that appeals to your reader and can be supported with evidence or explained at greater length in your body paragraphs. Then, the thesis looks like:

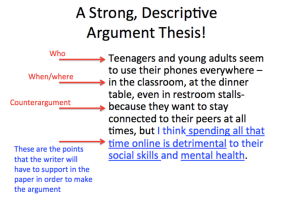

- Develop the parts of your thesis so it answers as many who, what, when, where, how, and why questions as possible. Your thesis is a one-sentence summary of your entire essay. Thus, you want your thesis statement to be something that you can unfold into a much longer work. And if your thesis makes a claim, that means it also answers a question. You can do this grammatically by adding prepositional phrases and “because” clauses that bring out the specifics of your argumentative thinking with confidence. Then, let’s see how the thesis could be revised:

Notice that this thesis, while not substantially different from the draft or working thesis we began with, has been significantly revised to be more specific, supported, and authoritative. It lays out an organized argument for a convincing paper. If you’d like to see a quick introduction to thesis statements, check out this video on Writing an Effective Thesis Statement.

Continue Reading: 7.5 Thesis Exercise and Checklist