2.2 Introduction to Academic Reading

You read everyday. In fact, you read more than you think you do because you are probably reading on a phone, a tablet, a computer, or other devices. So, what is “academic reading”? How is it different from casual reading? Academic reading demands your purposeful and intellectual engagement in the text. First of all, you as a reader must understand what you are reading and why you are reading it. At college, we read to build content knowledge because this knowledge is crucial to building an argument, which is the key to your academic career.

Of course, you need a different approach to a literary text for academic discussion and analysis. A literary text that does not have a clear argument and logical position requires us to understand elements of literature. For further reading and analysis of a literary text, see Chapter 26: Analyzing Literature.

How do we read effectively at college? Follow the five steps below.

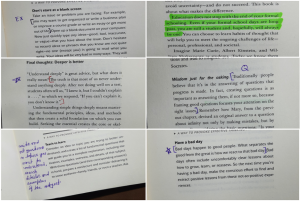

- Make notes while reading. Good readers almost always annotate the text as they read. An annotation is a special kind of note-taking directly on a piece of writing or text, usually in the margins of the page. The purpose of annotating is to aid your understanding of the text, engage in a conversation with the author of the text, and provide you with a reminder of your reading experience when you return to the text. People usually make notes in three ways. First, underline key words and phrases, which can appear useful when you need to quote for your analysis of the text. Second, summarize important ideas in a few phrases. Third, write down questions and thoughts that come up during reading. Observe how this book’s reader makes notes.

- Find a pattern of the text. All good writing has the same pattern: logical structure. Good readers know that almost all non-fiction texts—no matter the discipline, level of difficulty, or genre—follow pretty much the same pattern. The main idea comes at the beginning, the body paragraphs support the main idea, and the conclusion wraps up the whole thing. All the way back in grade school, you may have learned this formula for presenting your work: “Say what you are going to say, then say it, then say what you just said.”

- Understand a logical structure of the text. Good writers write clearly and use a specific structure. In order to be clear, they use the conventions of standard professional or academic non-fiction prose writing. If you know these conventions and their purpose, you will never get lost in someone’s written statement. You already know that most non-fiction texts have an introduction, a supporting body, and a conclusion, as we see above. These elements, too, are conventions. We can look for other conventions in addition to the introduction-body-conclusion structure. Here are common conventions in academic writing to notice. First, each paragraph carries one central idea. Second, one idea comes with evidence. Third, different ideas are related by transitions and transitional phrases, which create coherence and cohesiveness of an overarching argument. If you see this structure in reading, you can remember that clearly.

- See a big picture to understand an argument. As we examined earlier, the key to academic reading and writing is understanding and making an argument. This argument offers a big picture of a text. If you find unfamiliar words and jargon, you may want to give up reading. Hang in there! Using your pen or pencil, mark off the key conventional elements of the text and any other important features you notice at a glance. Then, read the introduction and conclusion. Next, read the first and last sentence of each paragraph. If that doesn’t give you the main idea of each paragraph, keep reading from the outside in until you get it. Write down the main points of these sections in the margins, on Post-its, or in your notes. This focused reading and writing will help you keep track of the main ideas of the whole article or essay or chapter, and when you see what you have written, you may be able to understand the work at a deeper level simply by imagining the connections between your annotations.

- Last, notice rhetorical features. When you listen to someone, the tone of the person’s voice reveals something beyond spoken words. You can “feel” the speaker’s sincerity when the person says, “I’m sorry.” To express that sentiment, what does the speaker do? You can consider the speaker’s gesture, tone, facial expressions, and other perceptible signs of her intention. In the same way, a writer uses various rhetorical features to express her intended meaning effectively. For further study of rhetorical features, see Chapter 5: Audience and Rhetoric.

Exercise: Practice Reading

Let’s practice reading academic writing effectively with Mike Bunn’s “How to Read Like a Writer.”

This is a good example of academic writing demonstrating an argument established through research of peer-reviewed articles and books.

What do you think about this essay? The anecdote in the beginning sounds interesting because we all have had that kind of job at some point. In this way, the writer starts his essay by gaining attention from his readers. On page 72, we as readers learn the author is going to tell us about “how reading in a particular way could also make me a better writer.”

First step. Grab a pen if you have the article printed. If not, download the file, and click an icon for annotation on the PDF. Underline key parts and mark the text with your notes, including your questions.

Second step. Let’s figure out the essay’s structure. Where is an introductory paragraph that carries a main argument? It is obvious that an introduction appears in the beginning. Note the subtitle, “What does it mean to read like a writer?” There, you can find a thesis. To you, what is his main argument? Note the structure by following the titles of the mini-chapters. All of them together make up the body of this essay with examples and sub-arguments.

These early two parts introduce a counterargument and defend his argument on reading like a writer. Someone would say, “So what? Why do we have to know?” You have to keep this counterargument in your mind because you can emphasize the importance of your argument by responding to a counterargument. Bunn places the significance of his argument here by placing the counterargument in the beginning.

After strengthening his argument, Bunn explains specific methods of his argument. This can guide the reader to understand its relevance and methodology, so that the reader can apply it to their own reading.

This last part serves as a conclusion of his essay. Instead of ending his argument as an abstract concept, Bunn offers practical examples for practice to emphasize his argument once more. If an essay is very long, you may feel lost somewhere in the middle of reading. Don’t worry. As long as you remember its main argument, which is introduced in the beginning, you are still in a safe corner. That is how you read like a writer. Then you will know how to write like a reader as well. I hope that you feel more confident in reading academic writing now!

Continue Reading: 2.3 Introduction to Academic Writing