5.3 Rhetorical Appeals

The Rhetorical Triangle

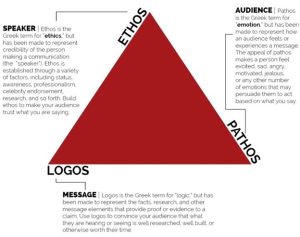

The principles that Aristotle laid out in his treatise on Rhetoric nearly 2,500 years ago still form the foundation of much of our contemporary practice of argument. The rhetorical situation Aristotle argued was present in any piece of communication is often illustrated with a triangle to suggest the interdependent relationships among its three elements: the voice (the speaker or writer), the audience (the intended listeners or readers), and the message (the text being conveyed).

Aristotle also described three different rhetorical strategies or appeals that a speaker or writer can use to make an argument effective. The three rhetorical appeals are ethos, pathos, and logos. These three appeals are guided by kairos, which is about timing. The three appeals may be used alone, but arguments are most effective when they combine appeals to ethos, pathos, and logos, with strong grounding in kairos or timeliness.

Ethos

A Greek word for “character,” ethos is an appeal to character, especially authority and expertise. That is, we often believe an argument because the argument is made by someone we respect. Ethos is often mistaken as an appeal to ethics. Though ethics are an aspect of a person’s or organization’s ethos, ethics are not the only component of character, authority, or expertise.

Celebrity and other endorsements are often based on ethos. Ethos is why an American Dental Association endorsement of a toothpaste is more powerful and generally holds more sway than an endorsement from a non-medical professional. At the same time, though, ethos as it relates to advertising is a bit complex. Sometimes people or organizations will have strong ethos not because they are professionals in a given field (such as dentistry) but because they may demonstrate the ideal results or benefits of a product.

Let’s take Sofia Vegara, for example. Vegara is a popular actor due to her role on the sitcom Modern Family. Her ethos as one of the world’s most beautiful people makes her an especially useful spokesperson for an array of personal care products, in part because she is known not only as an actor but as an attractive person. It is no surprise that she is a spokesperson for a variety of cosmetic and personal products, from Cover Girl makeup to Head and Shoulders shampoo. The latter product, though, is really where her ethos shines. Head and Shoulders is a dandruff shampoo, and generally, a flaky scalp is not associated with beauty. By having Vergara star in Head and Shoulders’ commercials, and further, having Vergara happily admit that her family has been using Head and Shoulders for over 20 years, the company relies on Vergara’s ethos as a confident, beautiful woman to combat embarrassment that some people (perhaps particularly women) may feel when faced with their own dandruff and flaky scalp and the need for a medicated shampoo. Vergara’s emphasis on how long her family has used Head and Shoulders even suggests that perhaps some of Vergara’s success in the beauty arena is due to Head and Shoulders.

Pathos

Originally, pathos described appeals to an audience’s sensibilities. Modern uses of pathos generally means an appeal to emotions, both positive and negative. That is, we often believe an argument because it makes us feel good (happy, proud, excited) or because it makes us feel poorly (scared, suspicious, angry). A rhetor may appeal to emotions that an audience already has about a subject, or a rhetor may try to make the audience feel those emotions.

Aristotle argued that emotions are central to our decision making, even if we are not consciously aware of it. If a rhetor desires to persuade a particular audience, then the rhetor must understand the ruling emotions regarding the topic and the specific audience. What makes the audience angry (or pleased), who or what is involved in producing or evoking that emotional state, and why does that particular audience become angry (or pleased) within a specific context? Knowing the answers to these questions will help a rhetor better prepare an argument and provide a basis for developing evidence and identifying counterarguments.

Appeals to pathos can sometimes be overwhelming and dominate an argument because emotions in general can be overwhelming. When emotions are strong enough, they can overtake logic and reason. That makes pathos sometimes misleading and dangerous, since it can use emotions to distract us from facts. Political campaigns are excellent examples of appeals to pathos. Political ads often play on the fears and hopes of different demographics. For example, a political ad aimed at retired and elderly voters may claim that a candidate plans on eliminating social support programs such as Medicare or will drastically cut Social Security benefits. These types of ads do not need to contain facts or evidence of such actions to be useful and successful because they rely on the fears and worries that the intended audience already has about financial and medical security.

Remember, pathos is about the emotional state of the audience, not the rhetor.

Logos

An appeal to logical reason, logos is about the clarity, consistency, and soundness of an argument, from the premise and structure to the evidence and support. A rhetor appeals to logos by making reasonable claims and supporting those claims with evidence, such as statistics, other data, and facts. However, logical and reasonable arguments and evidence are not universal across audiences, contexts, cultures, and times. What an audience considers reasonable claims and adequate evidence is influenced by an audience’s values and beliefs. Further, data and facts may evolve over time as we obtain more evidence, information, and data.

For example, some people believe the Federal Drug Administration is part of a conspiracy to cover up evidence that common vaccines cause a variety of neurological, psychological, and physical disorders, despite extensive scientific evidence from around the world that demonstrates common vaccines are safe. The scientific evidence is not reasonable or logical (and therefore not persuasive) for the conspiracy audience because the evidence may come from manufacturers of vaccines, FDA-sponsored studies, or researchers or studies with have connections to the FDA or other government agencies. However, for other audiences—such as those who are simply unsure about the actual benefits or reasons for vaccines—the same studies and data may be quite persuasive.

Kairos

Kairos is the Greek word for time. In Greek mythology, Kairos (the youngest son of Zeus) was the god of opportunities. In rhetoric, kairos refers to the opportune moment, or appropriateness, for persuading a particular audience about a particular subject. Kairos depends on a strong awareness of rhetorical situation. Kairos is the where, why, and when of persuasion. For example, nearly all op-eds and political essays are kairotic. The rhetors work to relate their ideas and messages to whatever is happening in the news and popular culture.

Continue Reading: 5.4 Logical, Emotional, and Ethical Fallacies