19.1 Introduction to Researched Writing

This chapter is about the process of researched writing. A lot of times, instructors and students tend to separate “thinking,” “researching,” and “writing” into different categories that aren’t necessarily very well connected. First you think, then you research, and then you write. The reality is that the process of researched writing is more complicated and much richer than that. We think about what it is we want to research and write about, but at the same time, we learn what to think based on our research and our writing. The goal of this chapter is to guide you through this process of researched writing by emphasizing a series of exercises that touch on different and related parts of the research process.

Sometimes, students think introductory college writing courses are merely an extension of the writing courses they took in high school. This is true for some, but for the majority of new college students, the sort of writing required in college is different from the sort of writing required in high school. College writing tends to be based more on research than high school writing. Further, college-level instructors generally expect a more sophisticated and thoughtful interpretation of research from student writers. It is not enough to merely use more research in your writing; you also have to be able to think and write about the research you’ve done.

Besides helping you write different kinds of projects where you use research to support a point, the concepts about research you will learn from this course and this chapter will help you become better consumers of information and research. And make no mistake about it: information that is (supposedly) backed up by research is everywhere in our day-to-day lives. News stories we see on television or read in magazines or newspapers are based on research. Legislators use research to argue for or against the passage of the laws that govern our society. Scientists use research to make progress in their work.

Even the most trivial information we all encounter is likely to be based on something that at least looks like research. Consider advertising: we are all familiar with “research-based” claims in advertising like “four out of five dentists agree” that a particular brand of toothpaste is the best, or that “studies show” that a specific type of deodorant keeps its wearers “fresh” longer. Advertisers use research like this in their advertisements for the same reason that scientists, news broadcasters, magazine writers, and just about anyone else trying to make a point uses research: it’s persuasive and convinces consumers to buy a particular brand of toothpaste.

This is not to say that every time we buy toothpaste we carefully mull over the research we’ve heard mentioned in advertisements. However, using research to persuade an audience must work on some level because it is one of the most commonly employed devices in advertising.

One of the best ways to better understand how we are affected by the research we encounter in our lives is to learn more about the process of research by becoming better and more careful critical readers, writers, and researchers. Part of that process will include the research-based writing you do in this course. In other words, this chapter will be useful in helping you deal with the practical and immediate concern of how to write essays and other writing projects for college classes, particularly ones that use research to support a point. But perhaps more significantly, these same skills can help you write and read research-based texts well beyond college.

What is Research?

When you hear the word research in a college class, what do you imagine? If an image of a scientist looking into a microscope pops in your mind, you have a sense of what research should be. Research is a process of collecting and investigating evidence to answer an academic inquiry objectively and persuasively. Research must involve a researcher’s reasonable method to find sources and critical interpretation of researched materials. For example, finding the capital city of Zimbabwe on Wikipedia is not research. However, if discovering the dynamic history of the country in the early twentieth century through academic journals and books leads you to explain the cultural and political significance of the capital city’s location, this can be considered research.

Research writing exists in a variety of different forms. For example, academics, journalists, or other researchers write articles for journals or magazines; academics, professional writers and almost anyone create web pages that both use research to make some sort of point and show readers how to find more research on a particular topic. All of these types of writing projects can be done by a single writer who seeks advice from others, or by a number of writers who collaborate on the project.

The Purpose of Research

Research does not end when you have found your answer. Imagine that a scientist collected enough evidence to prevent an invasion of a foreign predatory species, but she never shared her discovery with environmental organizations. Presenting what you have learned from research is just as important as performing the research. Research results can be presented in a variety of ways, but one of the most popular–and effective–presentation forms is the research paper. Having to write a research paper may feel intimidating at first. After all, researching and writing a paper requires a lot of time, effort, and organization. Nevertheless, the research process allows you to gain expertise on a topic of your choice, and the writing process helps you remember what you have learned and understand it on a deeper level.

Research Writing as a Process

As you may have seen in the earlier chapter, “The Writing Process,” research writing also follows the writing process from planning to revising. Nevertheless, research writing requires more specific skills to find sources and to incorporate them for your argumentation. No essay, story, or book (including this one) simply “appeared” one day from the writer’s brain; rather, all writings are made after the writer, with the help of others, works through the process of writing.

Before you start researching your topic, take time to plan your research and writing schedule. Research projects can take days, weeks, or even months to complete, depending on the scope and scale of your project. Creating a schedule is a good way to ensure that you do not end up being overwhelmed by all the work you have to do as the deadline approaches.

Generally speaking, the process of writing involves:

- Coming up with an idea (sometimes called brainstorming, invention or “pre-writing”);

- Writing a rough draft of that idea;

- Showing that rough draft to others to get feedback (peers, instructors, colleagues, etc.);

- Revising the draft (sometimes many times); and

- Proof-reading and editing to correct minor mistakes and errors.

An added component in the writing process of researched projects is, obviously, research. Rarely does research begin before at least some initial writing (even if it is nothing more than brainstorming or pre-writing exercises), and research is usually not completed until after the entire writing project is completed. Rather, research comes in to play at all parts of the process and can have a dramatic effect on the other parts of the process. Chances are you will need to do at least some simple research to develop an idea to write about in the first place. You might do the bulk of your research as you write your rough draft, though you will almost certainly have to do more research based on the revisions that you decide to make to your project.

There are two other things to think about within this simplified version of the process of writing. First, the process of writing always takes place for some reason or purpose and within some context that potentially changes the way you do these steps. The process that you will go through in writing for this class will be different from the process you go through in responding to an essay question on a Sociology midterm or from sending an email to a friend. This is true in part because your purposes for writing these different kinds of texts are simply different.

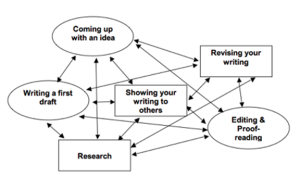

Second, the process of writing isn’t quite as linear and straight-forward as our list might suggest. Writers generally have to start by coming up with an idea, but writers often go back to their original idea and make changes in it after they write several drafts, do research, talk with others, and so on. The writing process might be more accurately represented like this:

Seem complicated? It is, or at least it can be.

So, instead of thinking of the writing process as an ordered list, you should think of it more as a “web” where different points can and do connect with each other in many different ways, and as a process that changes according to the demands of each writing project. While you might write an essay where you follow the steps in the writing process in order (from coming up with an idea all the way to proofreading), writers also find themselves following the writing process out of order all the time. That’s okay. The key thing to remember about the writing process is that it is a process made up of many different steps, and writers are rarely successful if they “just write.”

Continue Reading: 19.2 Getting Ready: Questions to Ask Yourself about Your Research Essay