22.8 Analyzing Story Elements in “Secrets and Gold”

As you read “Secrets and Gold,” you may have recognized it as fantasy fiction, as it is set in a fictional universe inspired by real world myths about dragons and witches. Fantasy fiction typically contains a system of magic and other supernatural elements in addition to the traditional story elements of plot, characterization, narration, and theme. Now that you have read the story carefully from beginning to end, it is time analyze the story, or to identify and discuss its elements.

One useful approach to identifying and mapping a story’s main events is the plot line. This plot line shows the basic plot points: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and denouement.

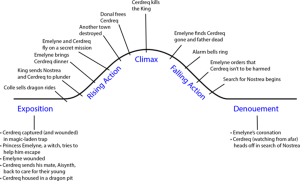

Begin by drawing a plot line on a piece of paper and considering how to map the story’s main events along the basic plot points. Remember, though, that story time, or the order of narrated events in a story, often differs from chronological order. Information about anything that happened before the story’s opening event is part of its exposition. LaRoche begins her story with Colle advertising dragon rides to the crowd while Cerdreq, the dragon, recalls—in a flashback—the day he fell into Nostrea’s trap and was captured. The events in that flashback are part of the story’s exposition, while the opening event of the storyline is Colle’s attempts to persuade the crowd to spend money to see or ride the dragon.

The interactions between the dragon and Emelyne are part of the rising action, as are the scenes involving the dragon and Nostrea or the interactions between Nostrea and the king. The climax of the story should be the point of the highest tension, not merely the midpoint of the story’s events. Not every reader will identify the same point as the climax, so be prepared to defend your choice. Students in my classes typically choose the moment that Cerdreq frees himself by killing the king with an avalanche of his own gold as the climax, identifying this as the pivotal point in the dragon’s quest for freedom. The remainder of the story–Cerdreq’s flight away from Aestavell, the discovery of the king’s and queen’s deaths, and Emelyne’s coronation are part of the story’s resolution, or conclusion.

The story is inhabited by people and animals, with Cerdreq and Emelyne being round, or developed, characters and Colle and the king being flat, or undeveloped by comparison. Nostrea seems to be only a minor character (playing a simpler, though important, role in the story’s outcome), and she may also seem stereotypical (as her character is based on overly generalized characteristics about the abilities of witches). LaRoche uses both direct and indirect characterization to bring her characters to life. For instance, the narrator describes Cerdreq, saying that the former “champion of the skies” is now “little more than a mangy pet to a human king.” On the other hand, readers see Colle capering about and calling to the crowd as he tries to attract customers.

As this story falls into the genre of fantasy, it is easily discernible that LaRoche is the author, or the person who wrote the story, but that she is not narrator, the person telling the story. LaRoche is located in the real world, bound by space and time, whereas her unnamed narrator lives in an imaginary realm that is not bound by the same physical laws as our own world. The teller of the story speaks from an external viewpoint, from somewhere outside the action, using third-person pronouns like he, his, she, her, it, and its. This is third-person narration, even though you may identify other pronouns within the story’s dialogue. While Colle addresses the crowd, for instance, he is not the narrator of the story. His words to his potential customers are enclosed in quotation marks, indicating that the narrator is relating exactly what Colle said to them. The narrator seems reliable, as Cerdreq’s captivity is described along with his wholescale destruction of nearby towns and villages. However, the story’s sympathetic attitude toward Cerdreq’s plight as he unsuccessfully struggles against his magic collar that forces him to bend to Nostrea’s will shows that the narrator is not entirely objective. By attributing the destruction of nearby villages and towns to Nostrea’s greediness and showing Cerdreq’s remorse for the devastation he caused, the narrator steers the reader toward the same sympathetic attitude. This is a narrator with limited omniscience, knowing only Cerdreq’s internal thoughts. The majority of the story is told from Cerdreq’s point of view. Near the end of the story, however, we see a narratorial shift, as the dragon escapes captivity and flies away, out of the reader’s sight. The narrator stays focused on the town of Aestavell, not the dragon. Within the story, several weeks pass before Cerdreq returns on the day of Emelyne’s coronation and is once again noticed by the narrator.

Returning again to your plot line, it should now look something like this (though no two plot lines will look exactly alike):

Notice that the story’s “exposition” contains events happening before the opening scene of the story, such as Cerdreq’s capture or Emelyne’s injury. On your own timeline, you might also want to note the passage of time or the names of specific towns or countries.

As mentioned above, “Secrets and Gold” is a fantasy, set in the fictional country of Aestavell in a world inhabited people, witches, and dragons. Aestavell is one of two countries mentioned in the story, with the Fens River separating between Aestavell and Evairis. Within these countries, specific cities, such as Ormkirk and Vathe, are mentioned, though the city where the dragon is housed is never named. While the imaginary location of Aestavell is obviously the “where” of the story, identifying its “when” is more difficult. Though more than six years pass with Cerdreq imprisoned in the pit, readers have no firm information about when the story takes place. Indeed, Aestavell seems a place overlooked by time. The region is located along an unidentified body of water large enough to require lighthouses to guide ships to harbor, villagers make their livings in traditional ways, like farming and blacksmithing, getting paid in gold rather than paper currency, and existing without the advantages provided by modern technologies. Dragon rides seem the only available means of flight, for instance, and communication takes place face to face, not via a telephone or computer. Aestavellian society is a monarchy, with the king ruling over the peasants, protecting the kingdom and enforcing order through military might. Injustice permeates the social order, with the king’s rapaciousness for gold leading to the impoverishment of his own people as well as the destruction of towns within neighboring kingdoms. The five kingdoms mark the extent of the story’s geographical reach, as the narrator evidences no knowledge of what lies beyond their borders.

Paying attention to the story’s publication helps us better understand the author’s use of story elements. Seven Deadly Sins: Avarice is a Young Adult anthology, meaning that the age and experience of the protagonists in the stories within the anthology correspond to its targeted audience: teenagers. (Keep in mind, however, that adults are voracious readers of YA fiction, making up approximately half of its readers.) Knowing that the story is designed for young adults helps us identify Emelyne as the protagonist of “Secrets and Gold.” She is the character who undergoes the most changes during the story. She begins life as a beautiful princess, loses the affection of her father when she is horribly maimed by a dragon blast, develops a sympathetic friendship with the captured mate of the dragon who injured her, embraces her magical powers to engineer her friend’s escape, and ascends to the monarchy upon the death of her father. Her coronation implies better, brighter days ahead for the long-oppressed citizens of Aestavall.

The story addresses many topics, including greed, friendship, social justice, abuse of power, and physical disabilities.

Identifying these topics allows us to begin possible thematic interpretations of the story. Here are some possibilities:

- Emeyne’s physical disability makes her not only more sympathetic to the wounded dragon but also to the plight of her future subjects.

- In “Secrets and Gold,” the unlikely friendship between Emelyne and Cerdreq is what heightens the princess’s awareness of her father’s greedy nature and builds her resolve to be a better person and ruler.

- The genre of fantasy allows LaRoche to provide readers with moral lessons about the power’s potential to corrupt without miring them down in discussions of contemporary world politics.

In an interview with me, LaRoche said that the subtitle of the anthology gave her the story’s primary topic–greed. Exploring this topic in a story for young adults was her motivation for writing, the point from which she then chose the genre of fantasy and began developing her fictional story world and characters. Her stylistic choices of using dialogue to move the story along and incorporating the highly popular elements of magic and dragons allow her to appeal to young readers, while her thematic investigations of greed, politics, power, physical disabilities, and social justice render her stories relevant to readers of all ages.

This initial analysis of “Secrets and Gold” provides us with a starting place for writing about the story, but it certainly does not address every possible story element or interpretation. The following questions are designed to thinking more deeply about the story, its elements, and your own interpretations.

Exercise

- How much time elapses in the story, and how do you know? What mechanisms does LaRoche use for controlling time within the story? Why would she choose to use these mechanisms and what are their effects on the pacing of the story?

- What do you make of the story’s final section, that ends with the dragon flying away in pursuit of the witch? Do you think the ending provides closure? Why or why not?

- LaRoche says that her primary topic in “Secrets and Gold” is greed, as that was also the assigned topic for the anthology in which this story appears. Which characters most exhibit the characteristic of greed and what are the outcomes of their greediness? Do you think the story fits the topic? Explain your answer.

- Like many fairy tales and fantasy stories, “Secrets and Gold” explores adult topics through the perspective of a young protagonist. While keeping your attention primarily on LaRoche’s story, make connections to other texts that you read as a child that you now realize did the same thing.

- Analyze the story in light of its title, “Secrets and Gold.” Who are the witches in the story, what magical powers do they possess, how do they use their powers, and what are their respective attitudes toward gold? Did the title give you any indication of the author’s stated theme: greed? If so, how? If not, why so?

Creative Commons Attributions

This chapter was authored and edited by Karin Hooks, Geoffrey Polk, and Amy Scott-Douglass. The sections on “How to Read a Play,” “Elements of Play,” and “Additional Strategies for Reading Plays” were written by Amy Scott-Douglass. The sections on “Story Elements” and “Analyzing Story Elements in ‘Secrets and Gold'” were written by Karin Hooks. Mari LaRoche’s story, “Secrets and Gold” is reprinted with permission by the author.

Other sections of this chapter contain material from Writing and Literature: Composition as Inquiry, Learning, Thinking, and Communication by Tanya Long Bennet, which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 International License as well as material from Writing and Critical Thinking Through Literature by Heather Ringo and Athena Kashyap, which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License.