23.5 The Elements of Fiction and Drama

Understanding the Elements of Fiction and Drama

Before you dive straight into your analysis of literature, you need to have a grasp of the basic elements of what you’re reading. When we read critically or analytically, we might disregard character, plot, setting, and theme as surface elements of a text. Aside from noting what they are and how they drive a story, we sometimes don’t pay much attention to these elements. However, characters and their interactions can reveal a great deal about human nature. Plot can act as a stand-in for real-world events just as setting can represent our world or an allegorical one. Theme is the heart of literature, exploring everything from love and war to childhood and aging.

With this in mind, you can begin your examination of literature with a “Who, What, When, Where, How?” approach. Ask yourself “Who are the characters?” “What is happening?” “When and where is it happening?” and “How does it happen?” The answers will give you character (who), plot (what and how), and setting (when and where). When you put these answers together, you can begin to figure out theme, and you will have a solid foundation on which to base your analysis.

We will be exploring several of the following literary elements in the following pages so that we can have a common vocabulary to be talk about fiction and drama:

- Plot

- Setting

- Characterization

- Narration and Point of View

- Conflict

- Theme

- Imagery

- Symbolism

- Style

Following are definitions of these elements and questions to consider when analyzing a literary work. We will be looking at some of these in more detail in the following pages.

Plot

The plot is the main sequence of events that make up the story.

- What are the most important events?

- How is the plot structured? Is it linear, chronological or does it move back and forth?

- Are there turning points, a climax and/or an anticlimax?

- Is the plot believable?

Setting

Setting is a description of where and when the story takes place. Ask yourself the following questions:

- What aspects make up the setting? Consider geography, weather, time of day, social conditions, etc.

- What role does setting play in the story? Is it an important part of the plot or theme? Or is it just a backdrop against which the action takes place?

Study the time period, which is also part of the setting, and ask yourself the following:

- When was the story written?

- Does it take place in the present, the past, or the future?

- How does the time period affect the language, atmosphere or social circumstances of the short story?

Characterization

Characterization deals with how the characters are described. Ask yourself the following:

- Who is the main character?

- Are the main character and other characters described through dialogue – by the way they speak (dialect or slang for instance)?

- Has the author described the characters by physical appearance, thoughts and feelings, and interaction (the way they act towards others)?

- Are they static/flat characters who do not change?

- Are they dynamic/round characters who DO change?

- What type of characters are they? What qualities stand out? Are they stereotypes?

- Are the characters believable?

Narration and Point of View

The narrator is the person telling the story. Point of view is whose eyes the story is being told through.

- Who is the narrator or speaker in the story?

- Is the narrator the main character?

- Does the author speak through one of the characters?

- Is the story written in the first person “I” point of view?

- Is the story written in a detached third person “he/she” point of view?

- Is the story written in an “all-knowing” 3rd person who can reveal what all the characters are thinking and doing at all times and in all places? Or is the story told through a narrator with limited omniscience, who can see into the minds and motives of only a few characters (or even a single character)?

Conflict

Conflict or tension is the heart of the story and is related to the main character. Conflict is a struggle between opposing forces. There may be outer and inner conflicts. A conflict is a misunderstanding or clash of interests that develops in the story. This often occurs between main characters. It drives the story forward and creates suspense.

- How would you describe the main conflict?

- Is it internal where the character suffers inwardly?

- is it external caused by the surroundings or environment the main character finds himself/herself in?

Theme

The theme is the main idea, lesson, or message in the literary work. It is usually an abstract, universal idea about the human condition, society or life, to name a few. A theme is the general subject the story revolves around. It often represents universal and timeless ideas that are relevant in most people’s lives.

- In a few words, what would you say the story is about? Often, the answer gives you clues to the story’s possible themes.

- How does the theme shine through in the story?

- Are any elements repeated that may suggest a theme?

- What other themes are there?

Imagery

As distinct from character, theme, and plot, imagery occurs primarily in language, in the metaphors (i.e. comparisons), similes (comparisons with “like” or “as”), or other forms of figurative (pictorial) language in a literary work. Sometimes setting, i.e., the locality or placing of scenes, or stage props (like swords, flowers, blood, winecups) can also be considered under the rubric of imagery. But whatever the expression, images primarily are visual and concrete, i.e., things which the reader sees or can imagine seeing. Some examples are flowers, tears, animals, the moon, sun, stars, diseases, floods, metals, darkness and light.

- Are there recurring images in the story?

- Look through your images and image clusters and see if they fall into any pattern. What are the interesting shifts? Do they generally appear in the speeches of certain characters? in certain scenes? Do we have a progression or development? Significant contrasts?

- How do the images relate to either the main point of the story or to some part of it? In other words, what do the images have to do with character or action? What are their effects on the story?

Symbolism

Symbolism is a practice of using symbols, or anything that represents something larger than itself. Common examples of symbols are a country’s flag and a heart symbol, which represent the country, and love. Each has suggestive meanings–the flag brings up thoughts of patriotism and a unified country, while a heart symbol implies feelings of love, affection, and emotion.

What is the value of using symbols in a literary text? Symbols in literature allow a writer to express a lot in a condensed manner. The meaning of a symbol is connotative or suggestive rather than definitive which allows for multiple interpretations.

Style

The author’s style has to do with the author’s vocabulary, use of imagery, and the tone or feeling of the story. The tone and feeling may come from the attitude (either implied or explicit) of the author, narrator, or characters. In some stories the tone can be ironic, humorous, cold, or dramatic.

- Is the text full of figurative language?

- Does the author use a lot of symbolism? Metaphors (comparisons that do not use “as” or “like”) or similes (comparisons that use “as” or “like”)?

- What images are used?

Analyzing the Elements of Literature

Next, let’s take a closer look at the elements of plot, character, setting, theme, and narration.

Plot

Before you can write an in-depth explanation of the themes, motives, or diction of a book, you need to be able to discuss one of its most basic elements: the story. If you can’t identify what has happened in a story, your writing will lack context. Writing your paper will be like trying to put together a complex puzzle without looking at the picture you’re supposed to create. Each piece is important, but without the bigger picture for reference, you and anyone watching will have a hard time understanding what is being assembled. Thus, you should look for “the bigger picture” in a book, poem, or play by reading for plot.

A plot is a storyline. We can define plot as the main events of a book, short story, play, poem, etc. and the way those events connect to one another. Conflicts act as the driving forces behind a plot.

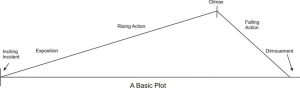

As we discussed earlier, a plot has several main elements: inciting incident, exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and dénouement. These elements often appear in the order listed here, but you should be aware that some works deviate from this form.

Inciting Incident: This is the event that sets the main conflict into motion. Without it, we could have no plot, as all the characters would already be living “happily ever after,” so to speak. Most stories contain many conflicts, so you will have to identify the main conflict before you can identify the inciting incident. Remember, the inciting incident and conflict are two separate things—the inciting incident is a moment in a story that starts the main conflict. For instance, a person throwing the first punch can be considered the inciting incident to the conflict of a long fistfight. In addition, the inciting incident can happen before a story takes place, in which case it is related to the reader as a past event.

Exposition: This is the part of the story that tells us the setting. We find out who the main characters are and where the story takes place. The exposition also hints at the themes and conflicts that will develop later in the story. Exposition can take place throughout a story as characters reveal more about themselves.

Rising Action: The rising action is comprised of a series of events that build up to the climax of the story. It introduces us to secondary conflicts and creates tension in the story. You can think of the rising action as the series of events that make the climax of the story possible.

Climax: The climax has often been described as the “turning point” of a story. A good way to think of it is the incident that allows the main conflict of a story to resolve. The climax allows characters to solve a problem. It takes many forms, such as an epiphany the protagonist has about himself, a battle between the protagonist and antagonist, or the culmination of an internal struggle.

Many stories actually have smaller climaxes before the main one. Like the main climax, these are turning points in the story. These sub-climaxes can be minor turning points in the main conflict that help build and release suspense during the rising action. They can also be the main turning points for secondary conflicts within a story.

Falling Action: The events that take place after the climax are called the falling action. These events show the results of the climax, and they act as a bridge between the climax and the dénouement.

Dénouement: The word dénouement comes from the French “to untie” and the Latin “knot,” which gives us an indication of its purpose. It serves as the unraveling of a plot–a resolution to a story. In the dénouement, the central conflict is resolved. However, conflicts aren’t always resolved. Some stories leave secondary conflicts unsettled, and a rare few even leave doubt about the resolution of the main conflict. The dénouement can also leave the story and characters in the same state they were in before the story began. This often occurs when an epilogue tells the reader that all the conflicts in the story have been resolved. Thus, we can see the dénouement as a kind of mirror to the exposition, showing us the same situation at both the beginning and end of a story.

Flashback (not shown in the diagram): A literary device used to give the reader background information that happened in the past.

Character

How do writers of prose fiction make us respond to the imaginary people they create? In order to encourage us to continue reading writers must force us to react in some way to their characters, whether it is to identify, empathize or sympathize with them, to dislike or disapprove of them, or to pass judgement on their actions, behavior and values. As we have already seen, the fundamental question we repeatedly ask when we read a story is what happened next. Equally importantly we want to know to whom it happened, and we will only want to know this if we feel strongly, one way or another about the characters in the story. In this respect the author’s skill at characterization is crucial.

We use the term characterization to describe the strategies that an author uses to present and develop the characters in a narrative. This use of descriptive techniques will vary from character to character. Some characters are central to a story; often there will be one main character, around whom the narrative revolves. Other characters may be much less thoroughly drawn; they may be introduced to the narrative primarily to perform a particular narrative or thematic function, and will probably undergo little or no change in the course of the story.

You are probably already adept at identifying the characters of a story, but there are some terms that will be helpful in your literary analysis. Keep in mind that characters aren’t necessarily people. They can be animals, divine beings, personifications, etc.

One of the most important terms you will use is conflict. Conflict occurs between two opposing sides in a story, usually centering on characters’ values, needs, or interests. A conflict can be internal or external. Internal conflict takes place within an individual, such as when a character is torn between duty to his family and duty to the state. External conflict occurs when two individuals or groups of individuals clash. A struggle between a character and his best friend is an example of an external conflict.

By examining the conflict, we can determine the protagonist and antagonist. The protagonist is the focal point of the conflict, meaning that he or she is the main character of the story. All the action in a story will revolve around its protagonist. In addition, a story that contains a series of conflicts can contain several protagonists–no story is limited to just one. The antagonist is the character who stands in opposition of the protagonist. The antagonist is the other half of the conflict. Remember that an antagonist doesn’t have to be a person–it can be a nation, a group, or even a set of ideas.

Sometimes, the protagonist can take the form of the antihero. The antihero is a protagonist who does not embody traditional “heroic” values. However, the reader will still sympathize with an antihero. For instance, a protagonist who is a scoundrel is an antihero, as a traditional hero would embody virtue.

In addition to the protagonist and antagonist, most stories have secondary or minor characters. These are the other characters in the story. They sometimes support the protagonist or antagonist in their struggles, and they sometimes never come into contact with the main characters.

Authors use minor characters for a variety of reasons. For instance, they can illustrate a different side of the main conflict, or they can highlight the traits of the main characters. One important type of minor character is called a foil. This character emphasizes the traits of a main character (usually the protagonist) through contrast. Thus, a foil will often be the polar opposite of the main character he or she highlights. Sometimes, the foil can take the form of a sidekick or friend. Other times, he or she might be someone who contends against the protagonist. For example, an author might use a decisive and determined foil to draw attention to a protagonist’s lack of resolve and motivation.

Finally, any character in a story can be an archetype. Readers often identify themes, tropes, symbolism, and archetypes that the author may have intentionally or unintentionally included. We can define archetype as an original model for a type of character, but that doesn’t fully explain the term. One way to think of an archetype is to think of how a bronze statue is made. First, the sculptor creates his design out of wax or clay. Next, he creates a fireproof mold around the original. After this is done, the sculptor can make as many of the same sculpture as he pleases. The original model is the equivalent to the archetype. Some popular archetypes are the trickster figure, such as Coyote in Native American myth or Brer Rabbit in African American folklore, and the femme fatale, like Pandora in Greek myth. Keep in mind that archetype simply means original pattern and does not always apply to characters. It can come in the form of an object, a narrative, etc. For instance, the apple in the Garden of Eden provides the object-based forbidden fruit archetype, and Odysseus’s voyage gives us the narrative-based journey home archetype.

Setting

If a story has characters and a plot, these elements must exist within some context. The frame of reference in which the story occurs is known as setting. The most basic definition of setting is one of place and time. You want to ask yourself “Where and when does the story take place?” Setting can be very important in discovering and highlighting the mood, or the general feeling we get from a story. (Note: Be careful not to mix up mood and tone, as they are not the same thing. Mood is the feeling we get from a story; tone is a way of getting that feeling across.) For instance, Edgar Allan Poe portrays a very dark, oppressive setting in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” which makes the reader share the narrator’s feelings of confinement and depression. In addition, the house in Poe’s story can be seen as a kind of internalized setting. In this kind of setting, an aspect of the story external to a character represents the character’s internal development. For instance, the cracked face of the house can be said to represent the cracked minds of the Usher siblings.

Setting doesn’t have to just include the physical elements of time and place. Setting can also refer to a story’s social and cultural context. There are two questions to consider when dealing with this kind of setting: “What is the cultural and social setting of the story?” and “What was the author’s cultural and social setting when the story was written?” The first question will help you analyze why characters make certain choices and act in certain manners. The second question will allow you to analyze why the author chose to have the characters act in this way.

Theme

Finally, you must examine theme in your basic analysis of literature. Theme is the unifying idea behind a story. It connects the plot points, conflicts, and characters to a major idea. It usually provides a broad statement about humanity, life, or our universe. We can think of theme, in its most basic definition, as the message the author tries to send his or her readers.

One thing you should remember about theme is that it must be expressed in a complete sentence. For instance, “discrimination” is not a theme; however, “genetic modification in humans is dangerous because it can result in discrimination” is a complete theme.

A story can have more than one theme, and it is often useful to question and analyze how the themes interact. For instance, does the story have conflicting themes? Or do a number of slightly different themes point the reader toward one conclusion? Sometimes the themes don’t have to connect– many stories use multiple themes in order to bring multiple ideas to the readers’ attention.

So how do we find theme in a work? One way is to examine motifs, or recurring elements in a story. If something appears a number of times within a story, it is likely of significance. A motif can be a statement, a place, an object, or even a sound. Motifs often lead us to discern a theme by drawing attention to it through repetition. In addition, motifs are often symbolic. They can represent any number of things, from a character’s childhood to the loss of a loved one. By examining what a motif symbolizes, you can extrapolate a story’s possible themes. For instance, a story might use a park to represent a character’s childhood. If the author makes constant references to the park, but we later see it replaced by a housing complex, we might draw conclusions about what the story is saying about childhood and the transition to adulthood.

Narration and Point of View

The narrator, or the person telling the story, is one of the most important aspects of a text. A narrator can be a character in the story, or he or she might not appear in the story at all. In addition, a text can have multiple narrators, providing the reader with a variety of viewpoints on the text. And finally, a story can be related by an unreliable narrator–a narrator the reader cannot trust to tell the facts of a story correctly or in an unbiased manner.

Note: One thing you should always keep in mind is that the narrator and author are different. The narrator exists within the context of the text and only exists in the story. However, in most non-fiction and some fiction, the author can model the narrator after themselves; in this case, the author and narrator are different people sharing the same viewpoint.

By point of view we mean from whose eyes the story is being told. All prose is written in one of three points-of-view: first-person narration, third-person limited narration, and third-person omniscient narration.

First-Person Narration

First-person narration is written in the first-person mode, meaning that that story is told from the viewpoint of one person who often uses language like “I,” “you,” or “we.” A first-person narrator can even be a character in the story she is narrating. Furthermore, the narrator will have a limited perspective; he cannot tell what the other characters are thinking or doing, and his telling of the story is influenced by his feelings about the other characters, the setting of the story, and the plot. When you read prose related by a first-person narrator, pay attention to the narrator’s biases–they can tell you a great deal about the other elements of the story. For instance, here’s an example of first-person narration:

As I walked home from the store, I could feel the cool spring breeze stir my hair. It was getting warm, and I had been looking forward to the end of snow, sleet, and rain for the past few months. I saw Charley coming down the sidewalk towards me. He was a nice guy, that Charley, but I always thought he was a few bulbs short of a chandelier. He waved at me, and I nodded in return.

As you can see, in the first-person mode, the narrator tells the story directly from his point-of-view. He has the ability to influence the reader’s opinions of characters through his narration– here the narrator explains Charley is not a very intelligent person. However, for all the reader knows, this could just be the narrator’s bias, not fact. Thus, when you read a story written in the first-person mode, look for evidence to support the narrator’s claims.

Third-Person Limited and Omniscient Narration

Third-person narration is related by someone who does not refer to themself and does not use “I,” “you,” or “we” when addressing the reader. Here’s the same story as above, told in third-person narration:

As Bill walked home from the store, he could feel the cool spring breeze stir his hair. It was getting warm, and he had been looking forward to the end of snow, sleet, and rain for the past few months. He saw Charley coming down the sidewalk towards him. Charley was a nice guy, but he was a few bulbs short of a chandelier. Charley waved at Bill, and he nodded in return.

In this example, the story is told by someone looking at the characters from an outside perspective. A third-person narrator will not be a character in a story, but an outside entity relating the story’s events. Third-person narrators rarely give biased accounts of events, but sometimes you will encounter an unreliable third-person narrator.

Some third-person narrators tell from a limited perspective. These narrators relate a story from one point of view, which is often the main character’s point of view. Because readers can only tell what that character is thinking and feeling, they have a limited perspective of what other characters are thinking and feeling. In addition, since only one character’s perspective is narrated, the audience gets to see the world through that character’s eyes; this can be good for revealing certain facts about setting and character, but it can also present a slightly biased story.

The other type of third-person narration is told from an omniscient perspective. This means that the narrator relates the story in third person but has access to all information in the story. The third-person omniscient mode is often used when an author wants to relate a text through the viewpoints of several characters. Third-person omniscient narrators tend to be the most reliable narrators, as they can present all the facts of a story.

Finally, you will sometimes encounter a story that is told in first-person narration by multiple narrators. When reading a multi-narrator text, you must always be aware of who is speaking. Multi-narrator prose provides the reader with as much insight about the characters as third-person omniscient narration does. However, because the reader only receives first-person accounts from each character, this kind of narration tends to be very biased. Thus, it is up to the reader to analyze the information provided by the narrators to reach conclusions about the story.

Narrative Organization

The way a story unfolds is as important as who tells it. Even though prose is just “regular writing,” there are many different kinds of prose. Some prose is written as short stories, while other prose is written as novels and novellas. Each type of prose has its own organizational scheme as well. For instance, some stories are organized into large sections, while others are organized into chapters. Some prose is even organized into sections of journal entries or letters between characters.

It is important to note how an author divides a story. In a novel, ask yourself why a chapter ends where it does. Does the chapter ending add suspense to the story, or does it just provide a place to transition to another character’s point of view? In a story, does each section of a story have its own theme, or is there only one overarching theme? Paying attention to how a text is organized and divided will provide you insight into the plot and theme.

Continue Reading: 23.6 Introduction to Poetry