Helen Fallon

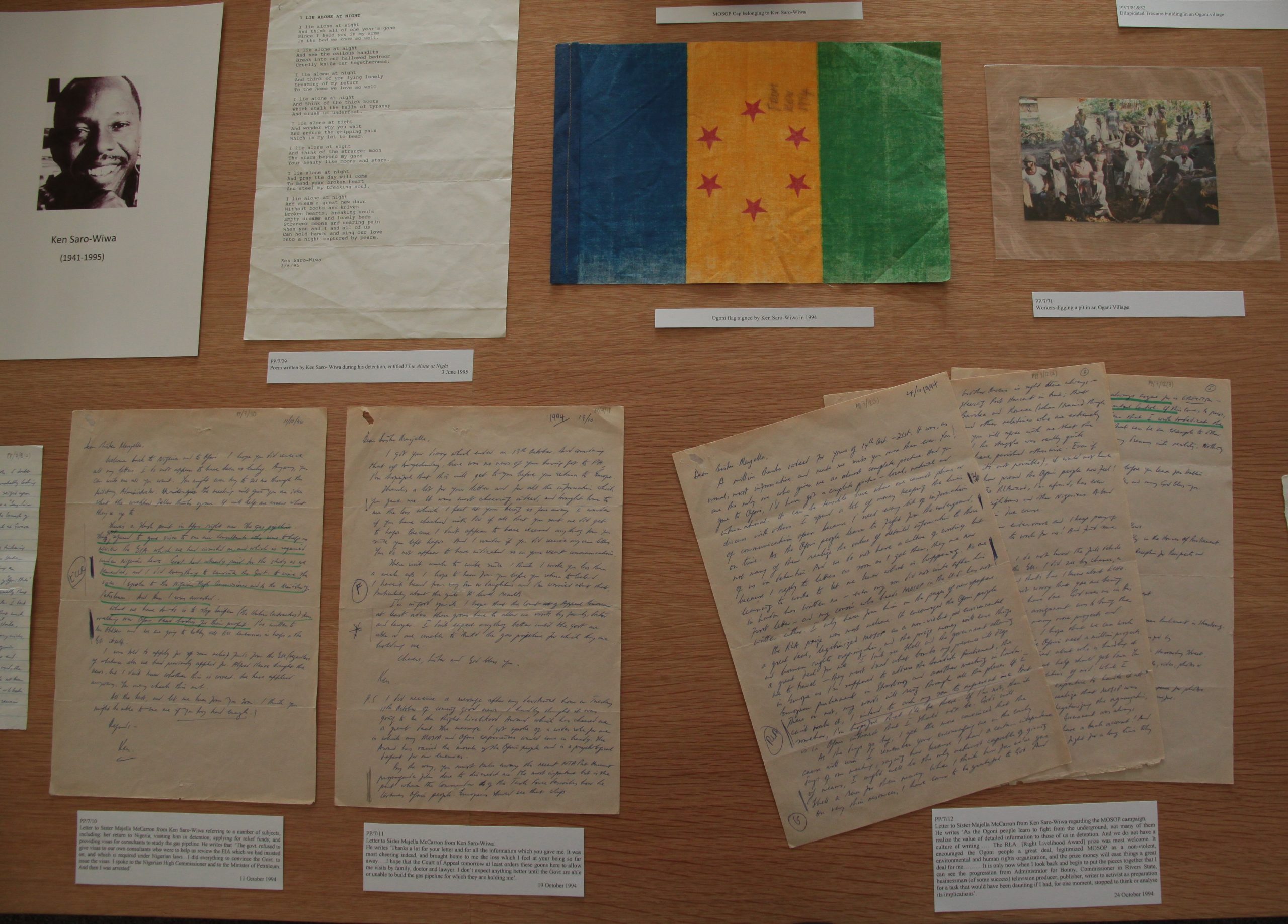

SR. MAJELLA MCCARRON (OLA) PRESENTED, on 10th November 2011, a collection of personal correspondence and 27 poems she had received from Nigerian writer and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa to the Library of Maynooth University. The date marked the sixteenth anniversary of Saro-Wiwa’s execution. Professor Philip Nolan, President of Maynooth University, accepted the gift from Sr. Majella on behalf of the University, saying, “the collection cast a very human eye on what was one of the late 20th century’s most troubling geopolitical issues”.

The collection comprises 28 letters to Sr. Majella, 27 poems, seven video cassette recordings of visits and meetings with family and friends after Saro-Wiwa’s death, a collection of photographs and other documents, including articles, reviews, flyers and maps relating to Saro-Wiwa’s work and the work of Sr. Majella on the cause of the Ogoni people, both in Nigeria and Ireland.

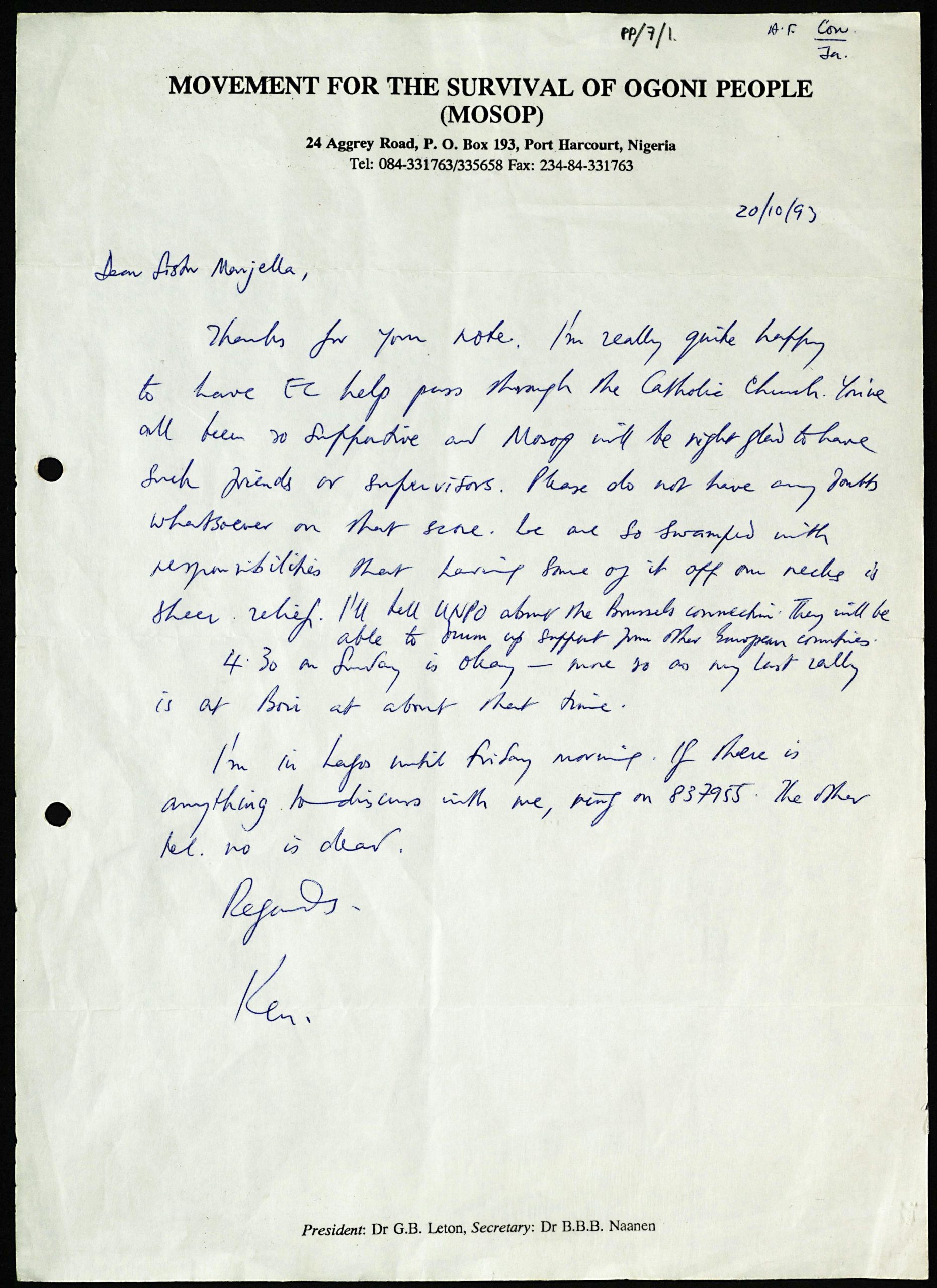

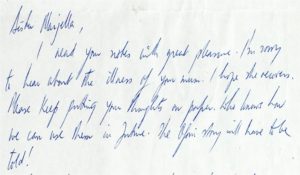

The letters were mainly handwritten between 20th October 1993 and 14th September 1995. The two earliest, dating from 1993, are from the period before Saro-Wiwa was taken into military detention: the first having been sent from his office in Port Harcourt, the second from Lagos. In May 1994 Saro-Wiwa and several other activists were placed in military detention in Port Harcourt. The letters written between July 1994 and his execution in November 1995 were smuggled out of detention in food baskets.

The letters cast light on Saro-Wiwa as a political activist, a writer, a family man and a personal friend to Sr. Majella. He wrote other letters during his captivity; apart from those to family and friends, he corresponded with Ethel Kennedy, Anita Roddick, Nelson Mandela, novelist William Boyd and other international figures. What makes the collection of letters to Sr. Majella unique is the relatively large number (28) and the combination of both personal and political content. Saro-Wiwa’s letters to Sr. Majella paint a picture of a well-educated and articulate Nigerian writer and illuminate his efforts to help the Ogoni people, who number less than 500,000 and live in the south eastern part of the Niger Delta.

While the letters tell a story of Ken Saro-Wiwa, we do not have the letters Sr. Majella sent to him to gain a more complete picture of this nun who left her rural home in Derrylin, County Fermanagh, to join the Missionary Institute of Our Lady of Apostles (OLA) in Cork in 1956. From there, armed with a science degree from University College Cork, she travelled to Nigeria. She initially taught science in a secondary school. Later, she completed postgraduate studies both in the University of Lagos and the University of Ibadan. In 1990, she was asked by the Missionary Institute of Our Lady of Apostles to do some work in Nigeria on its behalf. The Institute, a member of the Brussels-based Africa-Europe Faith and Justice Network (AEFJN), which lobbies the European Union on behalf of communities adversely impacted by European business, asked Sr. Majella to identify such communities in Nigeria. AEFJN offered to speak on their behalf at the EU. The oil problem in the Niger Delta region of South Eastern Nigeria was severe at the time, with major environmental damage being wrought by oil extraction. Saro-Wiwa, the leader of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), was organising a non-violent campaign against the environmental destruction of the Ogoni area of the Niger Delta. Sr. Majella brought the Ogoni complaint of environmental destruction by Royal Dutch Shell to the attention of AEFJN. He would eventually visit their office to offer his appreciation. Today AEFJN continues to monitor oil and gas impact throughout Africa.

When Sr. Majella selected this project, she had no idea how big it would become or of the strong relationship she would develop with Saro-Wiwa. She was initially introduced to him by Lynn Chukura, a prominent member of the Association of Nigerian Authors of which Saro-Wiwa was once president. Now deceased, Chukura, who was from Philadelphia, had lectured at the University of Lagos, the University of Ibadan and the University of Legon, Ghana. She was to give shelter to the wife and child of Ken’s brother Owens Wiwa in Lagos while he was avoiding arrest.

Sr. Majella was lecturing in Education at the University of Lagos when she met Saro-Wiwa. Academic institutions in Nigeria had frequent strikes and during one such period, she researched Ogoni issues. She visited Saro-Wiwa’s office in Lagos to consider with him how best to advance the Ogoni concerns. When Ogoni villages were destroyed in September 1993, Sr. Majella worked with the Daughters of Charity in Port Harcourt and Trócaire in Dublin to obtain a European Community grant for village relief. The first letter in the collection is Saro-Wiwa’s grateful response to her and offers MOSOP’s goodwill for the Church administration of this grant.

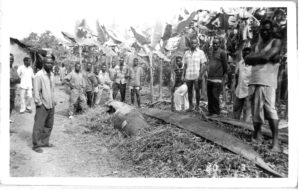

The collection contains photographs taken by Sr. Majella recording the destruction of the Ogoni villages, an act that was locally explained as a reactive punishment by unexplained forces to the campaign undertaken by MOSOP.

Another set of photographs records the efforts of Trócaire and the Daughters of Charity in the Catholic diocese of Port Harcourt to reconstruct houses in ten of these villages by means of the EC emergency aid she had helped to secure.

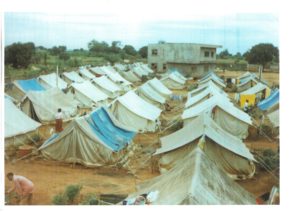

The collection also includes a third set of photographs which she received from a refugee camp set up in the Republic of Benin for fleeing Ogoni people. She was to keep in contact with this group and many other refugees in Europe and the US for several years.

Towards the end of 1993, Ken Saro-Wiwa discussed his concerns about developing the leadership potential of MOSOP with Sr. Majella. From her lecturing experience, she was familiar with a programme which used the psychosocial method of Paolo Freire, a Brazilian adult educator. His approach had spread through many grassroots communities internationally. In Nigeria, it had helped to shape the Development Education and Leadership Service administered by a team within the Catholic Church. Sr. Majella sought the assistance of one of its members, St. Patrick’s Society priest Tommy Hayden, and arranged a planning meeting with Saro-Wiwa in early October 1993. The first of a five-phase programme took place in 1993. While a second phase was planned for 1994, this was cancelled amid an outbreak of hostilities, turmoil and destruction.

It was an extremely dangerous time in Nigeria, with the Biafran war (1967-70) and the expulsion of missionaries still very prominent in people’s minds. The special security forces were very active and to be seen visiting the office of Saro-Wiwa was dangerous for Sr. Majella and others. “Anyone protesting in a military dictatorship places themselves in a dangerous position,” Sr. Majella commented in conversation with the author. She wrote observations on the Ogoni Movement, while Saro-Wiwa gave her regular updates, seeing her as a contact with the outside world—a way of getting his ideas and ideals out to a wider audience. “Ken and I used to talk at length about the problems concerning the Ogoni people. He appreciated my analysis and thoughts. I think he felt I was a benign, spiritual presence. I was a trusted witness,” Sr. Majella remarked.

In May 1994, Saro-Wiwa and other members of MOSOP were arrested. The twenty six letters dating from this time until his death were written in military detention. In a letter of 13th July 1994, he tells Sr. Majella he has managed to get a computer smuggled in so that he could continue with his writing. The urge to write is not just tied to the ideological conviction of the writer; for centuries, the commitment to write, despite expense and logistical difficulties, speaks of the pressing need for human contact. From military detention, Saro-Wiwa shared with Sr. Majella his thoughts on the Ogoni cause, his love for his family and friends and his passion for writing. On 13th July 1994, he wrote:

Have you been able to go through my essays: I wonder if they can be made into a book or should I take just the central ones and put them alongside the newspaper articles which I have collected? Seems to me that would be a better idea.[1]

The conversations that had begun in the Lagos office continued on paper; the high esteem in which Saro-Wiwa held Sr. Majella, and the value he placed on their contact as a window on the outside world, shines through in his letters. On 15th August 1994, he wrote to her in Ireland: “A million thanks for your letters. They are so entertaining, so encouraging, & they give me those intimate details of my family which no one else gives. God bless you & keep you for us!”[2] There is poignancy in his reference, in a letter dated 16th September 1994, to Sr. Majella’s visit to his family in London and her introduction to his newborn son: “It’s hard to think you’ve been away for a whole month! How fast does time fly? I saw your picture holding my young son Kwame whom I’m still to see.”[3] A fortnight later, on 1st October, he writes again, stressing her role in helping the Ogoni people:

I long to see you back in Nigeria, helping, among others, to guide the Ogoni people through the wilderness. You don’t know what help you have been to us and to me personally, intellectually. God grant that you do return to us. I’m counting the days.[4]

Sr. Majella did in fact return to Nigeria, on a short visit at the request of Trócaire, to finalise paperwork relating to various grants she had secured. She was not allowed to visit Saro-Wiwa during this period, but continued to correspond with him. The value of the correspondence in breaking his isolation was noted by Saro-Wiwa in a letter of the 24th October:

It was, as usual, most informative and made me miss you more than ever. You are the only one who gives me an almost complete picture. Had you gone to Ogoni, I’d have got a complete picture—local, national and international. It can be terrible here when one cannot phone or discuss with others.[5]

In October 1994, Saro-Wiwa was awarded the Right Livelihood Award, a Swedish prize presented annually, to honour people who make a significant contribution to solving modern-day challenges. He wrote his acceptance speech from his detention centre and Sr. Majella reviewed it for him. His request to attend the award ceremony, recorded in a letter of the 29th October, was refused by the military authorities. In December, Sr. Majella travelled to Stockholm for the ceremony. Photographs from the event are part of the collection donated to the Library. There is also an Ogoni flag which Saro-Wiwa listed among items for Majella to take to include in an exhibition in Stockholm to coincide with the presentation of the award. On Christmas Eve 1994, Saro-Wiwa wrote to her:

Dear Sr. M,

Thanks a million for your diaries of August, November and early December. It was really wonderful to hear all about the Stockholm Award Ceremony from your careful observant pen.[6]

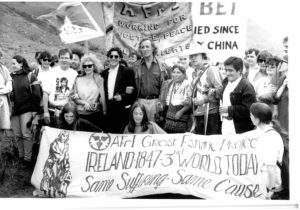

Sr. Majella devoted her sabbatical year to saving the lives of the Ogoni Nine through campaign work in Ireland. This led to the establishment of Ogoni Solidarity Ireland. Trócaire gave her the use of a phone and helped her to publicise the case of Saro-Wiwa and the eight others who were to be tried by a military tribunal. Photographs are included in the collection from this campaign. Her efforts offered some comfort to Saro-Wiwa, who wrote on the 21st March 1995:

I have seen your work & your pictures in the Irish Times and I think you yourself might be surprised how far those Ogoni bells are ringing now, and how you yourself have become the bellman. I thank God for your presence among us.[7]

In the last letter before his execution, dated 14th September 1995, he wrote of her letters:

[...]I believe that I’ve got everything you have sent thus far. Some of them come rather later and out of sequence, but I do get them. Because I keep them around me just to read and re-read them, I’ve had two of them seized lately. I hope that I will get them back, anyway, some day.

I expect that you have now started your new assignment and am really happy for you. It is hard to think that you will no longer be with us here in Nigeria, but it may well be that we shall be better served by your being away.[8]

She received this, his final letter, on 10th October, from his son, also named Ken, when he arrived in Belfast to receive a Nobel Peace Prize nomination secured by Mairéad Corrigan of the Peace People and supported by Amnesty International Northern Ireland, Trócaire Northern Ireland and the Bodyshop. The nomination was planned for Saro-Wiwa’s fifty-third birthday and was intended as a public appeal for the lives of the Ogoni Nine. One month later, their lives were taken at the behest of a military tribunal. It is very fitting that the collection now contains an e-mail from Mairéad Corrigan, herself a Nobel laureate, sent to Sr. Majella on reading newspaper coverage of the donation to Maynooth:

Dear Majella,

This is wonderful news that the life and writings of Ken Saro-Wiwa will be held at National University of Ireland Maynooth [9]. His life is a great testimony to the human spirit of love and compassion and self-sacrifice for others.

I had the great honour of having breakfast with Ken Saro-Wiwa during a Conference of UNPO in The Hague some years ago. He spoke with such love and passion about the plight of his people and also with love of his family particularly his son, who then was working as a journalist in London.

Ken would be pleased that you, his dear and faithful friend, have placed this material in the National University of Ireland Maynooth.

It’s amazing how things like letters remind us of our own connections and I am reminded too that you wrote to the Peace People about Ken and his Movement, so thank you Majella for all your work in supporting, during his lifetime, Ken and his people.

Ken Saro-Wiwa is considered to be one of the great environmental activists of the late 20th century and his letters reflect his passion for peace and justice around the world. Sr. Majella—an Irish female missionary charged with keeping Saro-Wiwa briefed and acting as the carrier of his message globally—is vital to this correspondence, having called the letters into existence. In his captivity, Saro-Wiwa must have drawn comfort from knowing the lengths to which Sr. Majella would go to ensure the delivery and protection of his written words. At a time when communications technology decreases the habit of traditional letter-writing, the enduring value of the letter in disseminating the voice of the oppressed remains. As a well-established writer, it is likely that Saro-Wiwa knew the letters were going to be read and considered in different contexts.

In gifting these letters to the Library at Maynooth University, Sr. Majella is ensuring the Ogoni story will continue to be told in many different contexts. These letters will be studied by students and researchers from a wide range of disciplines—Anthropology, Education, History, Economics, Geography, Sociology, Politics, Development Studies, African Studies, Archival Studies and Literature—all of which are represented in the courses offered at Maynooth University.

For this reason, the editors of this volume are grateful to Maynooth University sociology student, John O’Shea, who created the initial link between Sr. Majella and the University Library. In 2010, O’Shea interviewed her while working on his MA thesis. She told him about the Saro-Wiwa material she held and expressed an interest in finding an appropriate home for it, knowing the value this collection would have to present and future generations of scholars and activists. He contacted the Library and we immediately set about acquiring this unique collection. The Library already holds significant archives of writers, social and political figures, and missionaries and this collection will prove a most valuable addition in this area. The Ken Saro-Wiwa Collection complements our extant African holdings which comprise, among other works, a major collection of bibles representing 298 African languages, including Khana, Saro-Wiwa’s native tongue. Both on its own and in the context of broader themes which it so deftly illustrates, this donation marks a major new addition to our collections.

It is very timely that this donation has come shortly after the establishment of the Edward M Kennedy Institute for Conflict Intervention at Maynooth University, specialising in research on conflict resolution, leadership and civic engagement. The Saro-Wiwa correspondence will bring the lessons of the need for open dialogue around conflict to a wider audience— something the author was prevented from doing by his execution. Research of this nature needs to be happening at university level, where there are structures to support it and opportunities to share the findings globally. It is particularly appropriate that this research should be carried out in Maynooth University which has a long-standing commitment to equality and social justice.

The collection is now available in the Maynooth University Library for consultation. Archival and conservation work has been carried out, including cleaning and repairing documents that require attention, cataloguing each item and transferring the letters to acid free packaging materials. Future exhibitions will offer the opportunity for people to view the collection and the Library will provide a neutral space for people to become actively involved with Saro-Wiwa’s thoughts and experiences through his letters and other writings. Journal articles, research papers, theses and other work carried out on the Saro-Wiwa archive by staff and students of Maynooth University will be available—not just to the international research community but also to those involved in social movements all over the world. The letters have now been digitised and are available on open access.

The videos, which form part of the gift, record Sr. Majella’s visits to and meetings with the family and with the traditional authorities in Ken Saro-Wiwa’s home village of Bane as well as with members of the Methodist Church. There is an interesting Irish link here in that this was the earliest Christian missionary church in Ogoni and its missionaries were from the Kingston family of Cork, Ireland. This missionary family coordinated the translation of the Bible into Khana. The videos have been converted into more modern media to allow continuing access to the contents.

After the November 1995 executions of the Ogoni Nine, Sr. Majella continued to campaign on behalf of twenty more Ogoni detainees who were freed six years later. Much of the publicity material from this period is now with the collection.

These efforts were supported in Ireland by Trócaire, Action from Ireland, Amnesty International, the Bodyshop, the Peace People, many local groups from Cork to Donegal, a school in Dunboyne, and Belvedere College in Dublin. Ogoni Solidarity Ireland provided the essential focal point and Saro-Wiwa’s letters to Sr. Majella from May 1994 to July 1995 informed the Irish campaign before, during and long after the deaths of the Ogoni Nine. The material has been a source for the annual Saro-Wiwa Memorial Seminar organised by Sr. Majella in different venues every year since 1995, to consider the impact of multinational business on local communities in Ireland and elsewhere. Photographs from the collection, particularly that of a large mural remembering Ken Saro-Wiwa and his eight companions erected on the tenth anniversary of their death, record the connection between Ogoni and Erris in Mayo, Ireland. There are also photographic records of nine white crosses, situated opposite the Shell terminal at Ballinaboy, which were carried in campaigns. The letters informed Irish engagement with Shell in Nigeria and Ireland.

The letters, videos and other items are important historical and cultural artefacts, coming out of specific historical circumstances and specific human activity. The collection is part of the heritage of Saro-Wiwa, part of the heritage of Nigeria and particularly the Ogoni, and part of the heritage of the Sisters of Our Lady of the Apostles as represented by Sr. Majella in Nigeria. This wonderful donation comes at a particularly appropriate time. Our major new library extension has a purpose-built Archives and Special Collections area where material can be maintained, exhibited and consulted in the best possible environment.

In a letter of the 1st December 1993, Saro-Wiwa urged Sr. Majella: “Keep putting your thoughts on paper. Who knows how we can use them in future. The Ogoni story will have to be told!”[10] In gifting this material to the Library, Sr. Majella is ensuring that the Ogoni story will be told.

- MU archive PP/7/3[/f ootnote]

In August 1994, Sr. Majella returned to Ireland for a sabbatical, having decided not to renew her contract at the University of Lagos where she had taught for 13 years. On 30th July, prior to her departure, Ken writes simply,

“I will miss you in the year you are going to be away!”[footnote]MU archive PP/7/6 ↵

- MU archive PP/7/7 ↵

- MU archive PP/7/8 ↵

- MU archive PP/7/9 ↵

- MU archive PP/7/12 ↵

- MU archive PP/7/20 ↵

- MU archive PP/7/23 ↵

- MU archive PP/7/28 ↵

- since renamed Maynooth University — Ed. ↵

- MU archive PP7/2 ↵