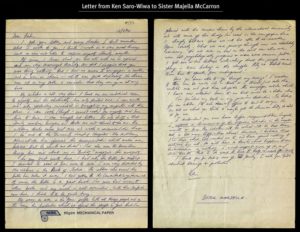

13/7/94

Dear Sr.,

I got your letter, and many thanks. I don’t remember what I wrote to you, I think I wrote in a very great hurry and so was not able to express myself clearly, maybe.

Of course, I know that you are all with me in spirit and am very encouraged thereby. Nor did I imagine that you were doing nothing. But I have no access to newspapers or radio, and I was in chains—which was quite depressing. The chains now sit on my table, a reminder that they can go on at any time.

My condition is not very bad. I have an air-conditioned room to myself, and the electricity has only failed once. I can write and only yesterday succeeded in smuggling my computer into this place. I can cook (though I cannot cook) for myself and from time to time, I can smuggle out letters.[1] The only thing is that family members, lawyers and doctor are not allowed to see me. The military doctor came just once and wrote a recommendation that I be sent to the University Teaching Hospital. The Military Administrator [Lt.-Col. Duada Musa Komo] has ignored the recommendation which makes me believe that he wants me dead. I’ve also seen the scurrilous things he’s said about me in Quality magazine. It’s annoying!

In my first month here, I had only the Bible for reading. I decided to read it from cover to cover. I was very disturbed by the violence in the book of Joshua. The soldier who owned the Bible has taken it away. I had gotten to the lamentations of Jeremiah. Of course, the Bible is a great book. I’ve since had access to other books and my mind is well-nourished. With the computer now here, I think I’ll be quite busy.

My worry, as ever, is the Ogoni people. With all MOSOP people out of the way, the protection which we offered the people is gone.[2] But I’m pleased with the concern shown by the international community and with some of the things I’ve read in the newspapers here. I strongly believe that we will be able to re-create Ogoni society. What we are passing through now was absolutely necessary. It’s not even as bad as the civil war when we were not psychologically prepared & were mere cannon fodder! I get one or two letters indicating that the people remain strong in their belief in the struggle. Pity we didn’t teach them how to operate from underground!

Have you been able to go through my essays? I wonder if they can be made into a book or I should just take the central ones and put them alongside the newspaper articles which I have now collected. Seems to me that would be a better idea.

I’ve finished my book on my previous detention. I’m looking for an editor. I’ll ask my office to send it to you. You can tell me what you think & maybe get the American lady to edit it for me.[3]

I understand you now have bigger responsibilities. Congrats. I expect a denouement of the Nigerian situation in the next month or two.[4] My situation will be solved with it, but there are a lot more difficulties ahead. However, I believe that I’ve done what God wanted me to, and have spared nothing to achieve his will. He will have to decide what happens to me. Incarceration is nothing. I must expect more of it, and even death. But I do want to live to help re-create Ogoni society.

I thank you for taking care of my family. I wish you God’s abundant blessings & protection.

Ken.

- Family members were required to supply food as was the norm in Nigerian prisons. The letters were smuggled in and out of the detention cell in food baskets. ↵

- Following the arrests and violence, many MOSOP members went into hiding. Some including the author’s brother, Owens Wiwa, had fled the country; a number received shelter at a refugee camp in Benin. ↵

- The book in question is A Month and a Day: A Detention Diary first published by Penguin books in 1995. The “American lady” to whom Saro-Wiwa refers is poet Lynn Chukura who came to Nigeria from Philadelphia to lecture in Lagos and Legon. As it turned out, she did not edit the manuscript. ↵

- On 12 June 1993, there was an attempt to restore civilian government. Abiola was elected but prevented by the military regime from taking office. Sani Abacha’s dictatorship continued until he died in 1998. Abiola died the same year. ↵