Laurence Cox

International solidarity between Africa and Ireland

THESE REMARKABLE LETTERS, from their writing to their publication, trace a history of international solidarity. Their origin lies in the relationship between Ken Saro-Wiwa, the wider Ogoni movement and Majella McCarron’s solidarity work, well-documented in Helen Fallon’s piece above. The letters themselves show Saro-Wiwa in action, mobilizing international support for himself and his co-defendants.

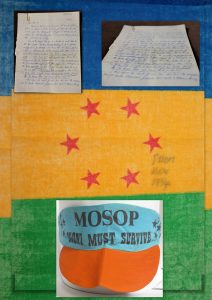

As he was only too aware, the situation of the “Ogoni Nine” symbolised the struggle between MOSOP, the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People, on the one side, and the Nigerian military government, together with the energy multinationals, on the other. To raise awareness and seek international solidarity for one was also to build support for the other. This strategy developed Saro-Wiwa’s earlier internationalisation of the conflict through participation in the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization and other fora.

When she returned to Ireland, Sr. Majella engaged closely with the Shell to Sea campaign of the equally remote community in Erris, County Mayo—the “Bogoni” as they sometimes called themselves—once again resisting Shell activities. As she made clear at the presentation of the letters, her choice of Maynooth University as a suitable repository for this historic collection is a result of the connections built up by Maynooth students working in solidarity with the campaign in Mayo, particularly John O’Shea, who suggested the donation; Jerrie Ann Sullivan, who recorded Irish police joking about the rape and deportation of protestors; and Terry Dunne, one of the original founders of the Rossport Solidarity Camp. Social movements can respect students and academics who take a stand on the basis of their own study and ethical choices; this engagement strengthens both civil society and intellectual work.

In turn, this publication would not have seen the light of day without the connection with Firoze Manji[1], the founder and former editor-in-chief of Pambazuka News, the pan African website and e-newsletter, who saw the significance of the letters at once and whose commitment to the project of publishing these letters has been exemplary. With this publication, the connection between African and Irish social movements comes full circle. But why should these movements exist in the first place?

The curse of oil: between Norway and Nigeria

The Norwegian specialist on oil and gas, Helge Ryggvik, speaks of the “curse of oil”. Finds of gas and oil only rarely benefit the local population. More commonly they lead to greater social and economic inequality, the corruption of the state apparatus and increased violence, as the rich and powerful use their existing advantages to monopolise the benefits of the new wealth.[2]

Norway, with all its complexities, is a rare exception to this rule. This is not because of any natural facts but because popular movements were determined that oil and gas wealth would be used for the benefit of society as a whole. In particular, civil servants who had been part of the resistance to fascism during the Second World War, an assertive trade union movement and popular commitment to social equality were crucial in pushing through the “Norwegian model” against the resistance of conservative elites and threats from the energy companies.

The essence of this was a productive model which gave multinationals limited access in the early phases in return for skill and technology transfer, which enabled Norway to build up its own industry, along with ownership and tax regimes which led to the Norwegian state’s petroleum fund becoming one of the world’s largest pension funds and financial investors.

Ireland and Norway both became independent from neighbouring powers in the early twentieth century; but Irish politics took different routes to the Norwegian, leading to the country becoming one of the most unequal in western Europe, with notoriously high levels of state corruption and clientelist power relations. It is this, rather than (as government ministers sometimes claim) some unique physical disadvantage vis-a-vis Norway, which has shaped Ireland’s response to oil and gas: a long-standing political commitment to enticing multinationals at any cost, coupled with the determination of local elites to secure small-scale advantages as middlemen in what has recently been called a “meet-and-greet” capitalism,[3] and the defeat and subordination of popular social movements.[4]

As the Navy is used to force through the Corrib pipeline in Mayo, further exploration rights are given away off the west coast, fracking is threatened across the west Midlands, and oilfields are announced off Dublin and Cork—all against a backdrop of IMF- and EU-mandated austerity and media cheers—the Irish future seems likely to be closer to Nigeria than Norway.

The Niger Delta and the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People

The people of the Niger Delta have suffered massively from their location on top of Nigeria’s oilfields. Their history, as Ken Saro-Wiwa wrote, has been one of a massively accelerated colonisation—the first British policemen arrived to impose imperial control as late as 1901 and conquest was only complete in 1914—tied to the then-crucial palm oil trade.[5]. Following the start of oil exploitation in the 1950s, multinational companies led a partial industrialisation, intertwined with internal colonisation by the newly independent Nigerian state.

Indigenous groups, in particular, suffer massively from their location in what are often strategic areas for extractive industries.[6] Ogoni are only one of several affected populations in this large and ethnically complex area. Such populations have truly been cursed by oil and gas: the vast bulk of Nigeria’s GDP and virtually all of its export revenue is generated here, where less than a quarter of the population live, and they are thus caught between the multinational energy companies—some of the world’s most powerful actors—and the national state.

The inequalities of high-tech industrial development side-by-side with rural poverty, the environmental devastation of blowouts, oil spills and the world’s largest flaring of natural gas, political marginalisation and police and military brutality have been the norm rather than the exception for indigenous groups in the Delta. From the Biafran war through to the current militarisation of the Delta, struggles for the control of the vast wealth represented by oil have taken place at the expense of local populations.[7]

As the newly independent African states’ pursuit of national economic development produced increasingly uneven distributions of wealth, repression of popular movements and ultimately acceptance of the “adjustment” packages of International Monetary Fund / World Bank austerity, poor rural groups and ethnic minorities suffered disproportionately from the deregulated economy. In the 1980s in particular, environmental movements revolving around the key resources of land, water, forests and so on challenged the state and multinational capital and connected this to the wider struggle for a people-centred democracy.[8]

MOSOP—the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People—was unusual in the history of resistance to this process in that it was determinedly democratic and non-violent; a truly popular mass movement aiming to secure popular control of this wealth, which did not simply reproduce the state’s own practices of violence.[9] As a federation of Ogoni organizations, including women’s and youth groups, churches and traditional leaders, students and teachers, it had particular legitimacy. In early 1993, something like 60% of the entire Ogoni population joined a coordinated day of protest—a virtually unheard-of level of participation.

The Ogoni Nine

The military response by the then dictatorship was one of characteristic brutality: demonstrators were shot, roads were sealed and villages were destroyed.[10] The trial of Ken Saro-Wiwa and the other members of the “Ogoni Nine” was part of this process. In 1994, four Ogoni chiefs were killed under circumstances which remain unclear.[11] Fifteen Ogoni men were charged with the murders, including Saro-Wiwa, who had been refused entry to Ogoniland on the day of the murders.

As the letters show, it was clear to Saro-Wiwa from early on that the court was rigged[12] and the intention was to execute MOSOP’s leaders in the belief this would end the movement. In fact, nine of the defendants, including Saro-Wiwa, were hanged, but the movement did not come to an end.

Instead, it was the dictatorship which fell in 1999.[13] State violence, it turns out, does not always win, and international outcry can make a dif-ference.[14] Nor did Shell win; it was declared persona non grata by MOSOP in 1993, subsequently left Ogoniland and eventually saw its operatorship handed over to the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation in 2011. A somewhat greater share of oil resources now go to Ogoniland, and the Ogoni movement continues.

Saro-Wiwa’s family, meanwhile, together with that of the other executed men, spent years pursuing Shell through the courts until they settled for over $15 million dollars. Court documents which have since become available make clear the extent to which Shell funded and instigated military operations against Ogoni activists in the Delta.[15] More recently, Wikileaks documents show Shell leadership boasting of their staff placed within Nigerian government departments and of exchanging intelligence with the US about militant activity in the Delta.[16]

Ken Saro-Wiwa and the letters

Ken Saro-Wiwa’s prison letters, like his son’s critical account[17], show him to be a genuinely remarkable figure and a social movement leader of great stature, who could draw on a breadth of political experience and historical vision. It is not too much to say that they bear comparison with the prison letters of the Italian anti-fascist leader Antonio Gramsci, which for decades have been staple reading for Italian schoolchildren.

At Gramsci’s trial, the prosecutor famously stated that “we” (fascists) must keep this brain from working for twenty years. Saro-Wiwa’s letters show his brain working at full speed, directing the campaign to halt the executions, developing strategy for MOSOP, and discussing the weakness of the Nigerian dictatorship. There is not only a clear analysis of the situation but also a hugely energetic activity directed not to saving his own life but to making sure that a death—which he in part expected—would serve the Ogoni movement and the end of dictatorship—as indeed it did.

Like Gramsci’s letters, Ken Saro-Wiwa’s prison letters deserve a wide readership. They are immensely readable, hugely enlightening and inspiring for all those who struggle for social and political justice. They show that even the world’s largest energy companies can be defeated; that even the most brutal and corrupt regimes do not necessarily win; and that even the smallest and most marginal populations, when they have their backs to the wall, a commitment to organising themselves and allies from other social movements, can find reasons to hope and act.

Your Ogoni, my Fermanagh

One of Saro-Wiwa’s poems, for Majella McCarron, sums this analysis—and his internationalism—up perfectly: “… reach out to the grassroots/ Of your Ogoni, my Fermanagh”. Ogoni’s situation is ours, and our situation is theirs; we can learn from each other.

The struggle for the democratic control of oil and gas resources, to ensure that when extracted their use is to benefit society as a whole and that only when appropriate ecological considerations prevail, is as global as the energy multinationals. Oil and gas go hand in hand with corrupt states, thuggish police forces, judges who do what they are told and a bought media.

They do not only bring out the worst in people, though; communities standing on their own land and fighting for their future existence often show extraordinary courage in the face of this intimidation, great generosity towards similar struggles elsewhere, a poetic vision of how we should live and a clear perspective of the realities not only of power but of the longer timescales in which we have to think if we want to have grandchildren and not simply bank accounts.

Ken Saro-Wiwa, in the letters collected here, exemplifies what human beings can be, in a standing reproach to the short-sighted, the vicious and the corrupt and a lasting inspiration to the wise, the decent and the brave.

- Firoze Manji, founder and former editor-in-chief of Pambazuka News, was head of CODESRIA’s Documentation and Information Centre <http://www.codesria. org>. He is the publisher of Daraja Press (https://darajapress.com). ↵

- Helge Ryggvik, Norway’s Oil Experience: A Toolbox for Managing Resources? Oslo: Centre for Technology, Innovation and Culture, University of Oslo, 2010. English translation available at <http://tinyurl.com/norwegianoil> ↵

- Conor McCabe, Sins of the Fathers: Tracing the Decisions that Shaped the Irish Economy (Dublin: The History Press, 2011) ↵

- Laurence Cox, “Gramsci in Mayo: a Marxist Perspective on Social Movements in Ireland”, Paper to New Agendas in Social Movement Studies Conference, Maynooth (2011) <http://eprints.nuim.ie/2889/> ↵

- Sanya Osha, “Birth of the Ogoni Protest Movement”, Journal of Asian and African Studies. 41.1/2 (2006): 13-38 ↵

- Declaration of the International Conference on Extractive Industries and Indigenous Peoples, Manila, 2009 ↵

- For an overview, see John Agbonifo, “Territorialising Niger Delta Conflicts: Place and Contentious Mobilisation”, Interface: a Journal for and about Social Movements 3.1: 240-265 <http://www.interfacejournal.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Interface-3-1-Agbonifo.pdf> ↵

- Cyril Obi, “Environmental Movements in Sub-Saharan Africa: a Political Ecology of Power and Conflict”, UN Research Institute for Social Development, Civil Society and Social Movements programme paper 15 (2005), online via <www.unrisd.org>. For wider overviews of social movements in Africa, see the Journal of Asian and African Studies special issue, “Political Subjectivities in Africa” 47.5; Peter Dwyer and Leo Zeilig, African Struggles Today: Social Movements Since Independence (Chicago: Haymarket, 2012); Miles Larmer, “Social Movement Struggles in Africa”, Review of African Political Economy 37.125: 251-262; Nikolai Brandeis and Bettina Engels, “Social Movements in Africa”, Stichproben: Wiener Zeitschrift für kritische Afrikastudien 20: 1-15, <http://www.univie. ac.at/ecco/stichproben/20_Einleitung.pdf>; and Michael Neocosmos, “Civil Society, Citizenship and the Politics of the (Im)Possible: Rethinking Militancy in Africa Today”, Interface: a Journal for and about Social Movements, 2.1: 263-334, <http://interfacejournal. nuim.ie/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Interface-1-2-pp263-334-Neocosmos. pdf> ↵

- Michael Neocosmos, “Transition, Human Rights and Violence: Rethinking a Liberal Political Relationship in the African Neo-colony”, Interface: a Journal for and about Social Movements, 3.2: 359-399, <http://www.interfacejournal.net/wordpress/wp-content/ uploads/2011/12/Interface-3-2-Neocosmos.pdf> ↵

- Elowyn Corby, “Ogoni People Struggle with Shell Oil” (2011), Global Nonviolent Action database, <http://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/ogoni-people-struggle-shell-oil-nigeria-1990-1995> ↵

- The Independent (London), “Ken Saro-Wiwa was Framed, Secret Evidence Shows”. 5th December 2010 ↵

- See the highly critical report on the trial for the Article 19 human rights NGO by Michael Birnbaum QC, “Nigeria: Human Rights Denied. Report of the Trial of Ken Saro-Wiwa and Others”. Article 19 (1995) <http://www.article19.org/data/files/pdfs/publications/nigeria-fundamental-rights-denied.pdf>. This notes among other things that the two principal witnesses subsequently swore affidavits claiming that they were bribed to give false evidence. ↵

- On the wider relationship between ethnic movements and democratisation, see Kehinde Olayode, “Ethno-nationalist Movements and Political Mobilisation in Africa: the Nigeria Experience (1990-2003)”, Stichproben: Wiener Zeitschrift für kritische Afrikastudien, 20: 69-93, <http://www.univie.ac.at/ecco/stichproben/20_Olayode.pdf> ↵

- Marie-Emmanuelle Pomerolle, “The Extraversion of Protest: Conditions, History and Use of the ‘International’ in Africa”, Review of African Political Economy, 37. 125: 263-279, rightly notes that internationalisation has costs as well as benefits; but few movements facing repressive regimes anywhere in the world have failed to appeal to movements and opinion abroad. ↵

- Guardian (London), “Shell Oil Paid Nigerian Military to Put Down Protests, Court Documents Show”, 3rd October 2011 ↵

- Guardian (London), “Wikileaks Cables: Shell’s Grip on Nigerian State Revealed”, 8th December 2010 ↵

- Ken Wiwa, In the Shadow of a Saint: a Son’s Journey to Understand his Father’s Legacy (London: Black Swan, 2001) ↵