Dr Anne O’Brien and Helen Fallon

KAIROS COMMUNICATIONS, under the direction of Dr Anne O’Brien, filmed the handover of the Ken Saro-Wiwa collection to Maynooth University in November 2011. From this and subsequently conversations the concept of an audio archive took root.

This is the story of the Ken Saro-Wiwa Audio Archive, which was created by Dr Anne O’Brien and Helen Fallon. The archive is freely available online. It has been accessed over 2,000 times since its creation and continues to be a living archive of people and events related to Ken Saro-Wiwa and his ideals.

Recordings

As of August 2018 there are 15 recordings in the audio archive and these can be accessed at:

https://www.maynoothuniversity.ie/library/collections/ken-saro-wiwa-audio-archive

Recordings 1-8 — The story of Sister Majella McCarron, from her childhood in rural Fermanagh to her work on social justice issues today.

Recording 9 — Dr Íde Corley discusses Ken Saro-wiwa’s position in post-colonial African literature and his role as a popular novelist and the creator of an award winning television sitcom.

Recording 10 — Helen Fallon discusses the Maynooth University acquisition of the Ken Saro-Wiwa collection.

Recording 11 — Dr Laurence Cox discusses Ken Saro-Wiwa’s legacy in terms of conflict over natural resources and the importance of the archive for both researchers and activists.

Recordings 12-14 — Dr Owens Wiwa talks about growing up in Ogoni, the environmental destruction of his homeland and the deaths of his brother and his colleagues. In recording 14, he reads two of his brother’s poems.

Recording 15 — An interview with Noo Saro-Wiwa.

While the archive of letters and images that McCarron donated to the library is immensely valuable, and the book Silence would be Treason offers an astute analysis of Saro-Wiwa’s work from a variety of perspectives, neither the archive nor the book entirely tell his story. The audio archive was designed to set out a more detailed and direct account of that story. Usually the hardest part of creating an audio archive is deciding on where the story is to be found. This was not the case with the Ken Saro-Wiwa audio archive, as the people who had the story were quite obvious, available, and willing to participate. In this case the story was most closely observed, from an Irish perspective by McCarron, and from a personal perspective by Saro-Wiwa’s brother, Owens Wiwa. The audio archive also contains an interview with Dr Íde Corley on post-colonial African literature; Helen Fallon talking about the importance of the letters and other materials in the collection, Dr Laurence Cox addressing the environmental issues and Noo Saro-Wiwa speaking about her father and life in Nigeria and London. These recordings complement their input to the written volume of letters and poems.

Arguably, it is the unique contribution of the audio archive that two of the people who worked most closely with Saro-Wiwa – Sister Majella and Owens Wiwa – were given the opportunity to speak for themselves, directly and in as unmediated a manner as was possible. Both of these people had so often had their version of Saro-Wiwa’s story told on their behalf, that it was important for them to have the opportunity to speak for themselves in an unconstrained manner. The absence of intervention in the telling of their versions of Saro-Wiwa’s story became a guiding principle for the production of the audio recordings. This allowed the contributors to maximise their imprint on the story, centrally guiding the subsequent editing process.

The key freedom involved in creating the audio archive, as opposed to working to the format, genre and scheduling constraints of broadcast documentary or feature programming, was that it offered as much ‘space’ as is required to tell the story in the fullest detail possible. While broadcast programmes limit the on-air time allocated to a programme and so limit the amount of material recorded at source, this was not the case with an open-ended time allocation. Seven hours of audio were recorded with McCarron.

This was free-ranging in the topics covered, from her Irish childhood, her education, her missionary work in Nigeria, the events that brought her to Saro-Wiwa, and all that passed subsequently. Hearing her story told in her own voice offers an insight into her personality and character that was not always as immediately conveyed in the written word. Moreover, hearing her voice first hand, with the intimacy this creates in recounting events in Nigeria leading up to Saro-Wiwa’s death, provokes a compelling intellectual and emotional awakening to the horror of the environmental abuse and destruction of Ogoni that she experienced first-hand.

Similarly, with Dr Owens Wiwa there was as much time available as needed to account for events in Ogoni and to tell the story of what had happened to his brother. Again, editorial intervention was minimised by recording the interviews as if they were being broadcast live. The interview with Owens Wiwa was recorded in a studio and there were no ‘retakes’ on any of the questions posed or answers offered. The interview as it exists in the archive is identical to that recorded in studio. This gave control of the final product, the archived version of the story to Owens Wiwa, rather than to an outside editor at a later point in time. In this way, by avoiding the possibility of editing, the audio archives can offer a safe ‘home’ to a story, a place where despite exclusion or misrepresentation in wider media, a story can be told and held with a minimum of editorial interference.

The interview with Noo Saro-Wiwa was recorded in a studio on her visit to Maynooth University on the 20th anniversary of her father’s execution.

She movingly told the story of how she found out about the death of her father:

I was a second year university student at King’s College London and he was sentenced to death – my father and his colleagues – on October 31st. So that came as a real shock, but then the international community really rallied round, so come November 10th it was just another day within that particular period. I must have attended classes, and then I went and did some shopping and I came back to the house I was living in in North London and my housemate had left a message, just a handwritten note on the table saying ‘call your mother’ and so I called my mother and she was the one who told me. I just put down the phone, which was the same reaction I had when I was told that my little brother died two years previously, I just put down the phone. And then went home immediately to my mother’s house and spent the evening with the family – my cousins and my aunt and uncle came over.”

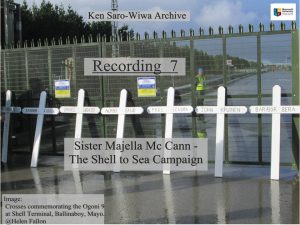

As to the mechanics of producing the audio archive, it is in essence a series of recorded interviews. Many were recorded on location. The two authors visited Rossport in Mayo with Sister Majella for the reinstatement of commemorative crosses for the Ogoni Nine at the Bellinanboy Shell terminal in November 2012.

Other interviews were recorded from the comfort of McCarron’s home, or in a car when nowhere more conveniently quiet presented itself. The aim in deciding the location for interview recordings was to make sure the sound was as ‘clean as possible’ to minimise distractions from the trajectory of the story itself. The interviews with Dr Owens Wiwa were recorded ‘as live’ in studio, when he came to Maynooth University to launch the book of his brother’s letters.

The interviews are, on first encounter, deceptively simple. They seem to meander through the story as if it is being told for the first time. This impression belies the volume of research that underpinned the detailed understanding of the story that the producers had acquired, the work involved in formulating and reformulating questions, and the care and time taken in conducting the interview on the day.

The recordings with Owens Wiwa attempted to follow best practice for interviews. There was no discussion of his brother or the ‘story’ prior to the recording, so that he did not feel he had already told the story, and might perhaps gloss over details in the interview. The session started with easy warm-up questions, such as childhood memories of his brother. This allowed the interviewee to settle into the interview and to get a feel for the right pace and tone of questions. From there the questions emerged from the chronology of events in Ogoni, leading up to Saro-Wiwa’s final detention. All the time, the interviewer needed to keep Owens Wiwa on the trail of the story while watching and reading how far he was able and willing to relive the detail of the destruction of Ogoni and in particular his brother’s death.

As the events recounted became more brutal and savage, the questions got shorter and simpler, relating to specific places and violent incidents – what happened at Biara? What happened in Kaa? Tell me about Oloko? These are simple questions that drove the narrative and were, for Owens Wiwa, the key turning points of the story; they shaped the topics that were discussed in the interview and gave the archive a route through a detailed and complex story that was coherent and manageable for non-expert listeners. Without thorough research and close listening, interviews don’t always yield the kinds of key personal insights that Owens Wiwa so generously offered. Despite close research, it is not unusual for an interviewer to be surprised by answers, for instance when questions don’t reveal the kind of insider tragedy or intimacy that was expected. When asked about the last time he had seen his brother Owens Wiwa gave quite an everyday answer, as if there was nothing of sentimental significance for him in the last meeting with his brother. In that case the unexpected answer is a useful reminder not to impose too much meaning or significance on events before the interview, but to remain alert to the dialogic exchange and possibilities that arise in the live telling of a story.

The archive required work in the pre-production phase, to gather as much information as possible on the story of Owens Wiwa and McCarron’s relationships with Saro-Wiwa, and to formulate questions that allowed for broad and wide-ranging responses, while still carrying the story forward in a manner accessible to non-experts. In production the recordings involved long sessions, so that the final archive would offer unlimited space to the contributor’s testimony. In post-production the editing was minimised, so that even apparently unrelated material was retained and valued as offering insights to McCarron’s character and presence. Hopefully, the archive can become a place in which a story can be ‘laid to rest,’ where it can reside indefinitely. McCarron commented that the archive could act as an overall record of her life and what had happened to Ogoni and to Saro-Wiwa. To that end, it is important that the audio archive is publicly available and accessible.

The Ken Saro-Wiwa audio archive, which was launched by Dr Owens Wiwa, alongside Silence Would be Treason, can be accessed online.

Between the launch on 7th November 2013 and 31 August 2017, the audio archive has been played over 2,000 times and has been widely promoted. At lectures and presentations on the audio archive, the audience never fail to be moved by the sound of Owens Wiwa’s voice, reading Ken’s poems Ogoni! Ogoni! or For Sister Majella McCarron. While academics and activists have spoken about Ken Saro-Wiwa in their research, through their publications and in their teaching, it is in the timber and accent of Owens Wiwa’s voice that Ken Saro-Wiwa really comes to life.

The Ken Saro-Wiwa Audio Archive provides an opportunity for students and the public to engage meaningfully with a complex and controversial topic that may seem very removed. There’s an old saying that ‘the pictures are better on radio.’ In the case of the Ken Saro Wiwa audio archive, that saying holds true. People listening to the recordings can construct mental images of the lives of the key protagonists in Ken Saro-Wiwa’s story and understand better the roles that Sister Majella McCarron and his brother Owens played in his life. There are no actual pictures to distract the imagination and so the listener can create their own landscape in an imagined Ogoni. But listeners don’t just think in terms of pictures; audio allows the user to access the part of the mind that generates dreams, to conjure more than a three-dimensional picture of Ogoni. Audio allows the listener to smell, feel and taste the world it creates. Listeners to the Ken Saro Wiwa audio archive can smell the gas flares, taste the polluted water and the touch the oil-encrusted, infertile spoiled land. In so doing they can clearly understand why Ken Saro-Wiwa created the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People. The audio archive brings home the fact that it was, and is, the survival of the people that was at stake.

Beyond Ogoni, the audio archive helps the listener to understand other issues too. In the immediacy of the first-person accounts and the intimacy of listening to another human voice, the passing of time collapses, the relevance and reality of events from decades ago become immediate. The audio archive, in this way, offers an insight into religious formation and convent life in 1950s Ireland. It gives an insider account of the thoughts and feelings of young missionaries travelling to Nigeria in the 1960s. Through Majella McCarron’s and Owens Wiwa’s recounting of their time with Ken Saro-Wiwa, particularly in the 1990s until his untimely death, the users are allowed to ‘see’ Ken Saro-Wiwa, not just as an activist who paid the ultimate price for his beliefs, but also as a friend and brother. Listening to the recordings, the users come to an understanding of the invisible ties that bind Sister Majella’s work in Nigeria with her activism today, against Shell in Erris, Co Mayo, in the West of Ireland. Somehow sound allows the listener to see very clearly the strong threads that connect the orator to the listener; the threads that also connect Ogoni to Ireland.

While recording that track of poetry for the archive, Owens Wiwa was asked if he would read from his brother’s letters. He refused, explaining that he felt to do so would be inappropriate as it would be to speak in his brother’s voice. On reflection, the most poignant aspect of the audio archive is the silence that lies at the heart of it, the listener doesn’t get to hear Ken’s voice. Throughout his life Ken fought for the rights of the Ogoni, and proclaimed that silence, in the face of their plight, would be treason. The stark fact remains, however, that Ken Saro Wiwa was silenced. That silence is in evidence amongst the voices of his ‘Sister Majella’ and his brother, Owens. It is a silence that offers testimony to the injustice and plight still suffered by Ogoni. Creating the Ken Saro-Wiwa Audio Archive is, the authors hope, a way to ensure the Ogoni story is not forgotten.