Person-First and Identity-First Language

Many people impacted by disability and/or disablement have a preference between person-first language like people/person with disabilities or identity-first language like disabled people/persons (Liebowitz, 2015; Kassenbrock, 2015). This language distinction is explained below.

| Person-first language |

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Identity-first language |

|

|

In this resource, we use both person-first and identity-first language to be inclusive of the various ways people self-identify. While persons with disabilities is the “politically correct” phrase often encouraged and used by public institutions right now, many disabled people prefer identity-first language. We recommend that you ask people their preference and use a variety of terms when you do not know.

Use of “Disability” Language

Students, staff, and faculty who legally, medically, and institutionally would qualify as having a disability for the purposes of rights protection and access to supports, may not identify with the language of “disability”. Some people only discover that the language of “disability” applies to them when filling in government forms or applying for accommodations, where this term is more widely used.

While some experiences of disability can feel very consistent over time, others may fluctuate over a lifetime (e.g. progressive gain of deafness or “loss” of hearing) or depending on context (e.g. sadness brought on by the time of year, pain triggered by weather changes or time spent sitting). This embodied fluidity can impact the language people use to describe their experiences or identify themselves over time and in different contexts.

Case Study:

Have you heard of the Forward Movement?

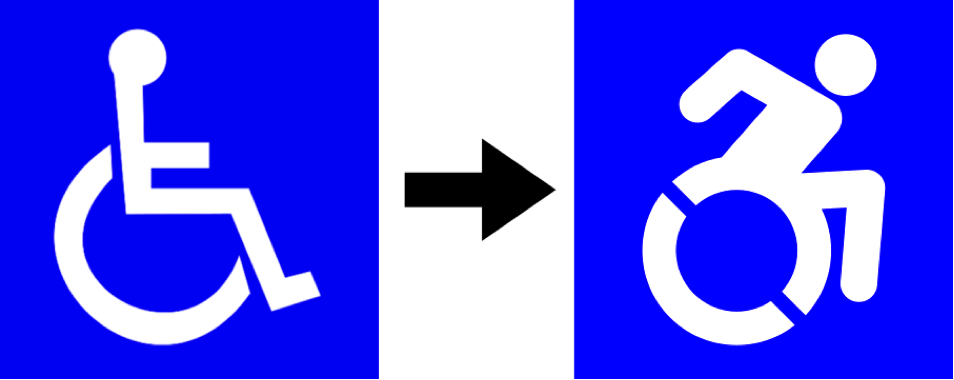

The Forward Movement (n.d.) advocates that we move away from the International Symbol of Access to instead adopt the Dynamic Symbol of Access.

As they describe on their website, “The current sign [with a blue background and white icon] depicts a stationary person with emphasis on the wheelchair. Portrayed in this way, people with disabilities are unfairly represented as unable to move, helpless and dependent”.

The Dynamic Symbol of Access, on the other hand, portrays a person in motion. The image presents a wheelchair user actively propelling themselves forward.

Read more on the Forward Movement website and sign their petition to legislate the use of the Dynamic Symbol of Access in Ontario.

Alternative Language and Identities

Instead of, or in addition to, using the language of “disability”, individuals may use descriptors like mental health concerns, chronic illness, trauma, or addiction. Some:

- relate to a diagnosis they have been given (e.g. lupus, Cerebral Palsy, Autism Spectrum Disorder, dyslexia, depression), and others

- have complex and shifting relationships to diagnoses.

It can be difficult for many people to both get (when it is desired or useful) and get rid of (when it is unwanted, unhelpful, or harmful) a diagnosis.

Case Study:

Did you know students are legally protected from disclosing a diagnosis?

- In early 2016, Navi Dhanota won a human rights case against York University, arguing that disclosing a specific diagnosis should not be necessary for accessing academic accommodations as a student (CBC News, 2016). Moving forward, students and employees seeking accommodation will not be asked to provide such specific and potentially pathologizing information (Condra & Condra, 2015; Ontario Human Rights Commission, 2017a).

Alternative Language

Some individuals may prefer to describe themselves and their experiences through:

- a connection to a disability community or politicized disability identity (e.g. psychiatric survivor, mad, neurodivergent, autistic, Deaf, self-advocate, voice hearer);

- in relation to the services they access (e.g. service user, consumer, patient, client); or

- in relation to other identities or disabling experiences (e.g. sexual assault or trauma survivor; experiencing grief or the impacts of systemic racism, transphobia, and/or poverty).

People often self-identify in different ways depending on the context.

It is important to resist making assumptions about the kinds of language someone may have access to or prefer to use to describe themselves or their communities of affiliation:

- It is generally best to avoid labelling people, and to use non-diagnostic and non-medical language instead (e.g. talking about energy or emotions rather than diagnosing someone’s experience as “bipolar” or medicalizing it as a disorder).

- Listen to the language people use to describe themselves and their communities and ask them which language they’d prefer you to use.

One important goal of enhancing accessibility in teaching and learning is to reduce the need for students to adopt the language of disability in order to communicate their needs or access their rights.

Accessible environments will support people identifying as having disabilities or experiencing disablement as well as those who understand and describe their experiences and barriers in different ways.

Continue Your Learning

- Listen to students with disabilities discuss approaches to self-identification and hear their suggestions for respectful language use in the classroom.

- Visit the door of Kenneth Taylor Hall 307A in the School of Social Work to read non-medical alternatives to pathologizing words that Mad students have developed, or view them online.

- Check out this glossary of words commonly used to talk about disability and accessibility.

- Recognize how disability is often misused as a metaphor rather than respected as an identity (Ben-Moshe, 2005).

- Appreciate how the euphemistic language of “differently abled” marginalizes disabled people (Brown, 2013).