This section picks up where Module 2 left off by connecting disability history and organizing to the furthering of accessibility in teaching and learning environments through Universal Design.

Disability Advocacy to Develop Universal Design

As discussed in the prior module on Disability History and Context, disabled people have been advocating for inclusion and against ableism for generations. One expression of this activism was the Barrier-Free Movement that began in the United States in the 1950s, when veterans disabled in World War II began to demand the removal of physical barriers that excluded them from civic and social life.

In keeping with the Social and Human Rights Model Approaches to disability, the Barrier-Free Movement questioned how physical environments were constructed for a “typical” able-bodied user, contributing to the ongoing exclusion of “unanticipated”, “atypical”, and disabled people. The Barrier-Free Movement challenged architects and inventors to rethink the design of physical environments and consumer goods so that they would be usable for a diverse range of users.

Universal Design principles emerged out of this context, promoting proactive design to avoid the construction of barriers, rather than reactive adjustments to mediate barriers that shouldn’t have been created in the first place. Universal Design is the opposite of the “one size fits all” approach; it is essentially the “no size fits all” but “multiple sizes and shapes and spaces are more likely to include most” approach (The Center for Universal Design, 2008).

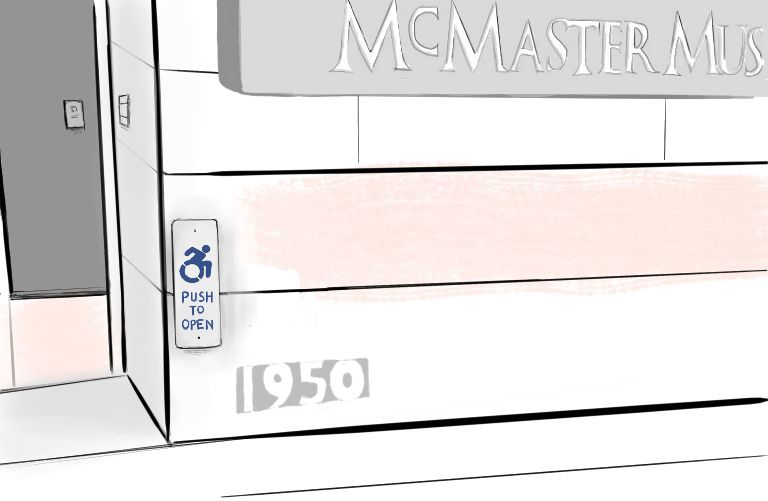

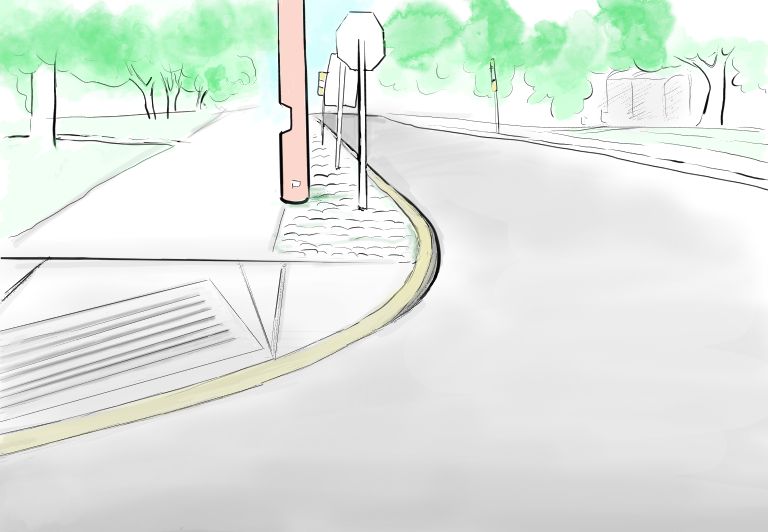

| For example: The Universal Design of ramps, push-button electronic doors, and curb cuts in sidewalks benefit many users, including those using wheelchairs or pushing strollers. In this way, the focus of Universal Design is not specifically on making modifications for disabled people, but on maximizing usability for everyone. Implementing Universal Design principles means avoiding the creation of and removing barriers so that all users can access a physical and social space (The Center for Universal Design, 2008). |

*Image of the push-button that opens the electric door entrance to the McMaster Museum of Art.*

*Image of a curb cut by the campus bus stop on Sterling Street.*

How does Universal Design relate to Accessible Education?

By the 1990s, principles of Universal Design were being adapted and applied to matters of curriculum and instruction. In this FLEX Forward resource, we focus on the research-based set of principles from Universal Design for Learning (UDL), which seek to optimize teaching and learning for everyone by designing educational environments with diverse learners in mind (CAST, Inc., 2017, n.p.).

The UDL framework aligns with the Social and Human Rights Model Approaches to disability by respecting the predictable and systematic variability in how human minds work – such as how we perceive, comprehend, and express learning, and in the ways we are motivated to learn (Torrisi-Steele, 2011). The social context we are raised in also influences how we learn to learn in different ways.

This difference is not an inherent deficit or problem. A problem is only created when our environments are designed in a way that include some learners and forms of learning and exclude others.

| For example: One person may learn more effectively by seeing words, while another might benefit more from hearing them, but neither visual nor aural recognition is superior. One person may best express their knowledge in the form of an oral story, while another might prefer to write in a linear manner. These differences should be understood, respected, and planned for so that no particular way of learning is valued or devalued over another. |

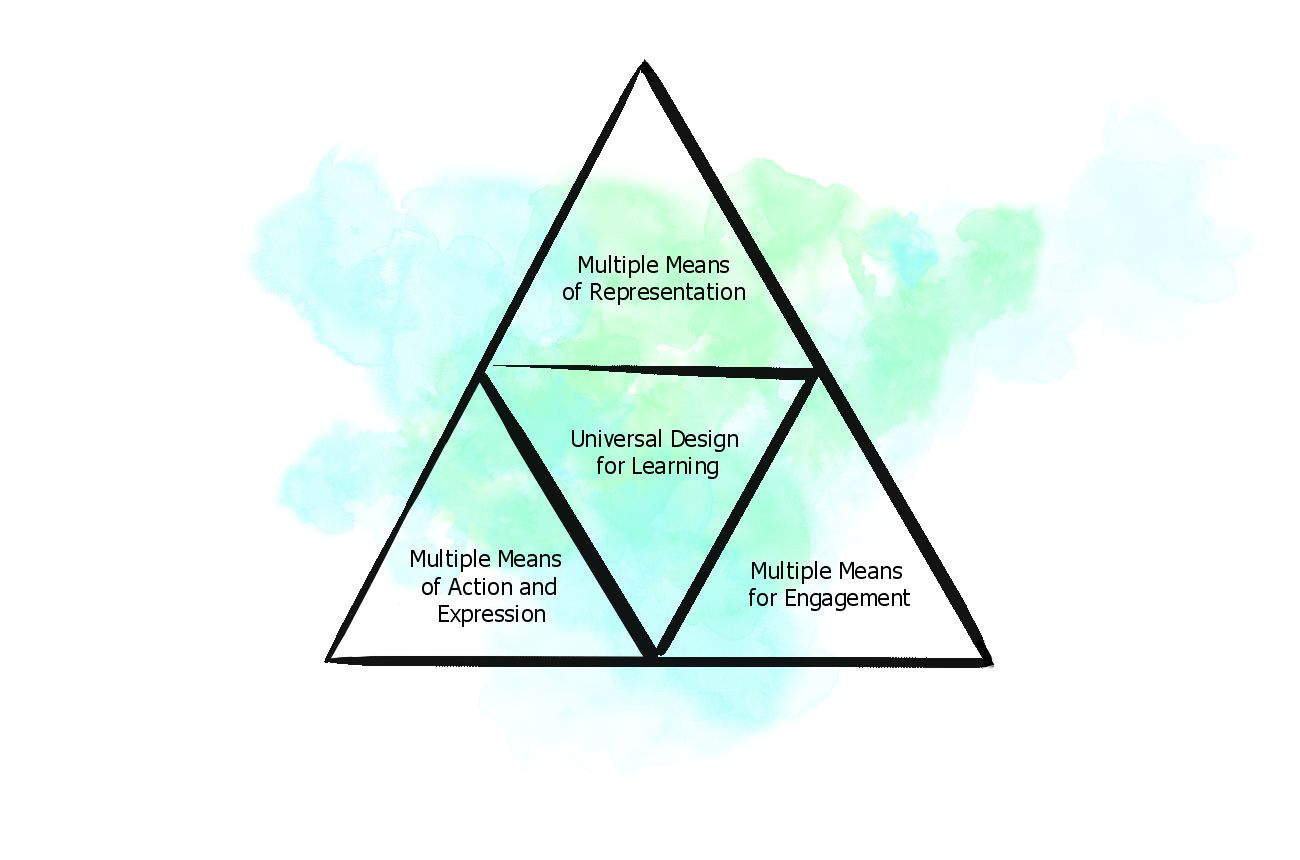

Dr. Jay Dolmage (2015) synthesizes a Universal Design for Learning approach to accessibility and supporting diverse ways of learning into the following 3 principles:

- Multiple means of representation;

- Multiple means of engagement; and

- Multiple means of action and expression.

Continue Your Learning

- Learn more about the seven principles of Universal Instructional Design (UID), a similar approach to accessibility in teaching and learning as UDL (University of Guelph)

Implementing Universal Design for Learning to Enhance Accessible Education: Flexibility & Variety

Given this recognition of and respect for variation among learners, and Dolmage’s (2015) encouragement to implement UDL principles by providing multiple options, this resource will put Accessible Education into practice through the methods of Flexibility and Variety.

| HOW can we FLEX Forward to advance Accessible Education? | |

| Flexibility |

|

| Variety |

|