Module 8. Our Way Forward

RACIAL & SOCIAL JUSTICE

At the beginning of our story, we asked if someone had ever misrepresented or taken advantage of you. We asked these questions to invoke an emotional frame of reference for you to begin to empathize and develop understanding about the impact of the United States and its history on people of color. It is difficult to comprehend another person’s pain, particularly if we have never experienced it ourselves, so we began with generalizations to help you build a mental bridge about the feelings that are invoked when you have been wronged or treated unfairly by others.

Racism and discrimination inflate race-based traumatic stress. Stress is a physiological and cognitive reaction to situations of perceived threats or challenges (Resler, 2019). Day-to-day stress is tolerable with coping skills and supportive relationships; however, exposure to adverse experiences over a long period of time can become harmful and toxic. Individuals experience toxic stress when they must maintain a level of hyper-vigilance to unpredictable or dangerous environments. Being a racial minority leads to greater stress because of the prevalence of systemic racism and racial discrimination (Resler, 2019). Racial minorities are in a constant state of red alert from having to anticipate racial events and interactions and being cognitively aware of how to respond appropriately for survival. Racial trauma can result in psychological affliction, behavioral exhaustion, and physiological distress (Comas-Diaz and Jacobsen, 2001).

When we are confronted by pain or trauma inflicted by others, we either develop adaptive strategies or change-oriented strategies to cope. Depending on the social conditions, our responses to such social and psychological distress vary. Minority groups, as a whole, function the same way by adapting to or changing the status quo.

There are four common adaptive responses to subordinate or minority status: acceptance, displaced aggression, avoidance, and assimilation (Farley, 2010). Each adaptive response consents to having unequal status and attempts to adjust or live within the social system. Acceptance involves the greatest degree of giving into a subordinate position. Some minorities accept inferior status because they are convinced the ideology of the dominant group is superior, others believe they cannot change their situation and become apathetic, and several pretend to accept their status by playing on dominant group prejudices such as acting dumb to fool the majority and navigate social contexts (Farley, 2010).

Displaced aggression is another adaptive response to subordinate status. In social systems where people are powerless, frustration and hopelessness are directed towards each other rather than the dominant group. Because minorities are oppressed by the dominant group and the power structure does not permit a mechanism for them to retaliate or strike back, they displace their emotions and aggression onto each other (Farley, 2010). Examples are seen in communities of color where minority group members commit violent acts on one another. In a state of displaced aggression, it is common for minorities to scapegoat or blame each other for their lack of power and lower status. Fighting each other releases the pain of being powerless while also inflating the misnomer of having more power than their minority group counterparts.

Another common method for adapting to subordinate status is avoidance. Some minority group members avoid contact with the dominant group to cope with the state of being powerless. By avoiding contact with the dominant group, minorities are able to forget or ignore their subordinate status (Farley, 2010). As a way of avoiding their inferior reality, other minority group members attempt to escape by using drugs and alcohol.

Lastly, assimilation is a way minority group members adapt to subordinate status. Assimilation necessitates minority group members to become part of or accepted by the majority or dominant group. This response relies heavily on socially and culturally transforming one’s position or role in society (Farley, 2010). To become part of the majority group or be accepted by the group, minorities must pass or fit into the dominant white culture. In an effort to assimilate, minority group members practice code switching where they alternate between their native or indigenous self into an assimilated and acculturated self.

BIOGRAPHICAL REFLECTION 8.1

THE BLUE MORNINGS

As a child, one of my earliest memories was of the “blue mornings.” That time before the sun rises when the night is almost gone. When I was about six-years-old, I used to wake up afraid because my three other siblings and I were in a strange place, waiting for my mom to come home from wherever she was. I worried about her never coming back.

My childhood had many blue mornings of fear and sadness. My grandmother was from Mexico, and she embodied everything that a Mexican grandmother could be. She died around this time, and suddenly, my 26-year-old mother, who was addicted to heroin, and had four children that she was not used to taking care of, was now motherless, and we were motherless as well as my grandmother had become our mother.

On the next blue morning I remember, my mother was arrested, and we had to go live in a foster home with relatives. I woke up to a year of blue mornings without her because she was in prison for a year. I worried about her and wondered whether she was safe. I was so excited to get mail from her which usually had beautiful drawings.

When she was released from prison, it seemed like we were all going to be together, and we were for about a year. She and my stepfather were both on parole, and we had parole agents visiting our home. That “family chapter” would come to a screeching halt when my stepfather was shot and killed in front of our home later that summer. We moved immediately to stay with my grandfather for a few weeks.

My mother found a boyfriend soon after and left us to move to Los Angeles with him. These blue mornings were packed with fear. We went back to a foster home to live with relatives until she got a place and could come and get us. She eventually did, about two years later, and we lived with her for a few months.

We came home from school one day, while living in Los Angeles, to a packed-up home. My mother announced that we were leaving to go back to Fresno. We were on a Greyhound bus headed back to Fresno to live in a migrant camp for a few weeks, then back to the foster home. These blue mornings were ones of exhaustion. We stayed there for two years until we got to high school.

Throughout the blue mornings of moving, grief, loss, trauma, fear, abandonment, and more loss, God was there. Even if we were the poorest people I knew, even if we moved every school year, even if my mother was lost and was not paying attention to God…he was paying attention to us, we were protected.

The most profound blue morning was a blessing that came at age 21. I committed to a life of faith that included forgiveness and hope for a future. My blue mornings were times that I prayed and spent time with God in the process of building a different life. This helped me develop a life that was not defined by my upbringing, but instead, redefined. I realized the gift of being born in a country where I had resources and the ability to get educated as a woman of color. Refined in the understanding that I was given many tools to help me step up and out of this life. I also recognized that not everyone is given the same. Because of those blessings, I did well in school and ultimately became a parole agent myself. I recently retired from that career after 25 years and am now a professor of Criminal Justice at a local junior college. God did that. There were so many jobs I was not qualified for, so many instances when the answer should have been no, but it was yes.

In the thousands of blue mornings that I spent with Him…He healed me…He helped me…He restored me…He defined me.

He transformed the blue mornings from a time of sadness trauma to a time of gratitude and hope. Now, the blue mornings are a time that I walk and take in the new day with so much hope. They are the times that I pray and cry out in appreciation for what I get to wake up to every day. The blue mornings no longer represent fear, trauma, loss, and rejection, but represent my special time with God. The time that he reminds me, it’s always bluest before daybreak. It is the best time.

This story “The Blue Mornings” by Guadalupe Capozzi is licensed under CC BY NC ND 4.0

Rather than adapt or accept subordinate status, some minority groups focus on change-oriented responses. Change-oriented responses focus on altering majority-minority relations and transforming the role of the minority group in the social structure and system (Farley, 2010). The goal is to increase the political, social, and economic power of the group while preserving its culture. Change-oriented responses are realized and implemented through social movements. A social movement is an organized effort to bring about social change. Social movements can develop on the local, national, or global level (Conerly, Holmes, & Tamang, 2021).

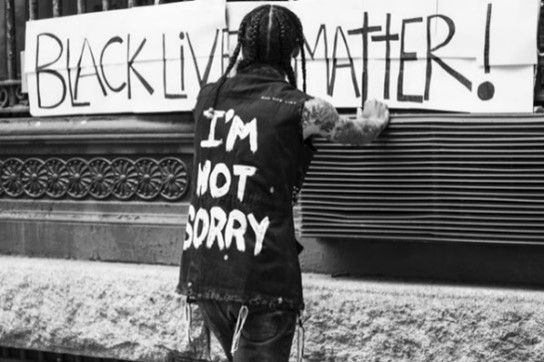

David Aberle (1966) observed and categorized six types of social movements. The first are reform movements which concentrate on modifying a part of social structure or system. Black Lives Matter is a reform movement motivated to stop police brutality by pressuring elected officials and law enforcement agencies to change policing practices. The second are revolutionary movements that center on changing society. The Civil Rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s worked to gain equality rights under the law for Black Americans in the United States. Religious or redemptive movements converge to provoke spiritual growth or change in people. American Indian Residential Schools of the mid-17th through early 21st centuries forced Native American children to give up their culture, language, and religion in an effort to assimilate them into Euro-American ideologies and beliefs. Alternative movements focus on self-improvement both in transforming personal beliefs and behaviors. Anti-Racist practices and support for Critical Race Theory are spreading throughout the United States specifically among White Americans. This alternative movement is grounded in the premise that race is socially constructed and used to oppress and exploit people of color in the United States. Finally, resistance movements strive for preventing change to existing social structures or systems. White supremacy groups involving the American Front, Klu Klux Klan, Proud Boys, and Christian Identity are participating in resistance movements throughout the United States. In California alone, there 72 active white nationalist hate groups supporting resistance (Southern Poverty Law Center, 2020).

Awareness leads people to start a social movement for change or resistance. An effective social movement must have an organized course of action to achieve a goal, a method to create interest or promote the movement, a message to communicate the significance for change or resistance, and a large number of unified and committed people supporting the cause. Social movements develop and evolve in five stages: (1) initial unrest and agitation, (2) mobilization, (3) organization, (4) institutionalization, and (5) organizational decline and possible resurgence (Henslin, 2011). The longevity of a social movement and its effectiveness strongly depend on the ability to maintain involvement of a large group of people over time.

Other social and environmental factors influence the effectiveness of a social movement to create or resist change. The physical environment affects the development of organizations including social movements. People organize their activities and way of life relative to weather conditions. A second factor of success is the political organization or structure of a society (i.e., democratic, authoritarian, etc.). Political authorities have the power to mobilize a community and political agencies can strongly affect the course of development and action in a society. Culture is another stimulating factor of efficacy. Social change requires transformation of social and cultural institutions religion, communication systems, and leadership. If society is not prepared for change, then it will resist so a social movement’s success depends on the cultural climate of the community. Lastly, the mass media serves as a gatekeeper for social change by either spreading information supporting or contradicting a movement’s message (Henslin, 2011). If social movements are unable to reach a large number of people, they cannot form an organized course of action.