Module 3. Our Story: Native Americans

WESTWARD EXPANSION

Most of the 19th century was a time of great turmoil and despair for Native Americans. The U.S. government approached relations with Natives in two different ways, first removal and relocation; then land redistribution and assimilation.

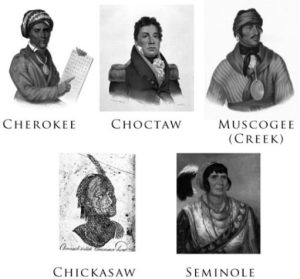

Between the 1820s up through the 1880s, Native Americans were continually uprooted and relocated to reservation lands. These actions were legitimized by the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, under President Andrew Jackson. This act passed with President Jackson’s approval and was later carried out under his predecessor Martin Van Buren. President Jackson claimed that Native Americans were “uncontrolled possessors” of their lands, and therefore would only be allowed to occupy lands that were given to them by their conquerors (Jackson, 1829; Richter, 2001). The act allowed for the removal of five different tribes from their ancestral lands to relocate to reservation territory in modern day Oklahoma. The former lands would later be settled by White Americans.

In a shift of tactics, instead of using force to combat the removal process, one of the five tribes, the Cherokee, sought to work within the U.S. legal system to sue for their rights to their land. This was an uphill battle, especially after Georgians discovered gold in Cherokee territory in 1829, making their territory highly coveted. After tumultuous court battles, in Worcester v. Georgia, the Supreme Court upheld Cherokee rights to their lands. Unfortunately, even this court ruling was not enough to protect the tribes, and over the course of several years, the five tribes: Chicksaw, Choctaw, Seminole, Creek, and the Cherokee were forced from their homelands to a territory west of the Mississippi River. The removal process took several years and was later named the Trail of Tears. The reason for the name was because the relocated Natives took the forced journey on foot, many of them dying of exposure, disease, and starvation. Men, women, children, the elderly, the infirm – they were all forced to walk with their possessions, no wagons, no horses, tents, or provisions. One in three died on the journey, and they barely made it to their destination.

APPLICATION 3.1

SHIFTING PERSPECTIVE: CHEROKEE INDIANS

Goal

To understand the experiences of the Cherokee Indians in protesting Indian Removal policies.

Instructions

Read the Cherokee Petition Protesting Removal, 1836. Answer the following questions:

- What reasons does the speaker use to protest removal?

- What kinds of language does the speaker use to describe U.S. policies?

The interactions between the Americans and Native Americans during the 19th century were justified by a concept that was coined into words by John O’Sullivan in the 1840s – Manifest Destiny. O’Sullivan successfully illustrated a concept that was already ingrained in the minds Americans since the initial settlement of this country. Manifest destiny was the belief that Americans had a destiny, a calling that could not be changed. That destiny was to inhabit the lands of North America from the Atlantic coast to the Pacific coast. Additionally, O’Sullivan was clear that this “destiny” was dictated by God, underpinning this concept with the most prevalent religion in America of the time, Protestant Christianity. By giving this concept a name, O’Sullivan gave Americans a justification to continue to settle and occupy all the lands in North America, continually pushing westward no matter what was in their way because it was their destiny. What he really conceptualized were the beliefs and desires of even the earliest colonists, who had journeyed west across the Atlantic Ocean so long before him. In this era, Manifest Destiny was not merely about colonial settlement, but American domination of land, resources, and societal order.

This maltreatment continued amidst the American civil war. Even as the country was torn by armed conflict, American citizens kept a steady pace on their quest for westward expansion. In what is Minnesota today, the Dakota tribes fought for their rights to remain in control of their lands in a conflict called the Dakota (Sioux) Uprising of 1862. Because of the severe depletion of buffalo herds, which was the tribe’s main food source, the Dakota tribes resorted to farming, which was not working out well. The tribes were then forced to resort to asking the state government for aid, or buying food on credit, or else their people would starve. Local authorities refused to comply and tensions rose. A group of Dakota men killed five White settlers, and violence continued to escalate into war with the Dakotas. By the time local militias ended the violence, hundreds of Dakotas were taken prisoners and held accountable in courts of local authorities where murder, rape, and atrocities took place. Officially, 303 Dakota tribal members were sentenced to be hanged, until President Lincoln stepped in and commuted most of the sentences to 38 individuals. This was the largest mass execution by hanging in U.S. history. The remaining members of the local Dakota tribes were chased into the hills, hunted, killed, and starved out.

After the events of the Dakota Uprising, more and more violent incursions occurred. In 1864, the Arapahoe and Cheyenne tribes attempted to protect their lands in Colorado. However, when gold was discovered on their lands, Americans sought to gain access. The tribes sought peace negotiations, but Colorado militiamen forged a different path. In a violent attack called the Sand Creek Massacre, a White militia openly attacked the tribes at Sand Creek, killing over 200, forcing those survivors onto reservations. In 1886, former Union soldiers forced the Navajo into a similar trek as the Five Civilized Tribes in the Long Walk, wherein thousands perished on their way to reservation lands from their New Mexico homelands. Any tribal members that resisted were shot.

Driven by a so-called campaign of peace, President Ulysses Grant attempted a different approach, closing this era of removal and relocation. In a post-war effort, Grant instituted a ‘Peace Plan’ to “conquer through kindness.” This plan was called the Dawes General Allotment Act or the Dawes Act of 1887. The goal falsely presented as a plan to redistribute and protect land rights but turned out to be another process of denial of land rights. The Dawes Act revoked collective land ownership from the tribes and redistributed the land in smaller plots to individuals within the tribes. Tribal members would be given the deed to those plots of land after they had lived on that land for 25 years. Only after the 25 years of probation would the individuals receive the land titles, and some would even be granted citizenship.

This legislation had multiple issues. First, it denied the traditional communal land use that generally, Native Americans had practiced. Customarily, no individual owned land, but they utilized it as a collective unit. Second, it assumed that tribes were not capable of holding a land deed. This part of the act was intended to defend Natives from criminal land prospectors or sneaky investors, but it also assumed that tribal members were too inexperienced and unintelligent to recognize unfair deals. Next, much land was taken during the allotment era, never released by the government to Native Americans. Lastly the law withheld land titles for the span of a generation on purpose, to award the lands to the next generation of children that had most likely gone through Indian boarding schools meant to Americanize or assimilate Native American children into American culture. The last point leads to the next issue at hand – education.

Native American education in the U.S. during the 19th century was similar to other marginalized groups such as immigrant communities. For Native Americans, the outcome was much more detrimental to the culture. Education for these groups was tailored towards one goal – assimilation into American culture, also known as Americanization. This is the process of deemphasizing the original culture of a group and indoctrinating students to what was generally acceptable American culture. For example, language was a prevailing tactic to shift children towards American culture by forcing children to speak English rather than their Native language. For children of immigrants, this was problematic but practical, for they could remain bilingual, speaking one language at school and another at home. For Native Americans, this was cultural erasure, for the elder tribal members were continually being eradicated through warfare and the children were being forced to forget their native language. Through the Americanization process, the loss of Native American culture and custom was paramount. There was no home country where their languages and customs still existed because they were still in it. Their culture was just simply being erased.

The 19th century was extremely damaging to Native Americans – due to the breaking of treaties, erasure of culture, and outright genocide. The future of Native Americans was uncertain, and the next century would prove to be just as tumultuous.