153 What is Argumentation?

Key Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to

- Describe the features of argumentative writing

- Define different types of argumentative claims

This chapter on argumentation discusses what is meant by “argumentation” and provides methods and examples for writing an argument of your own. Overall, a well-written argument essay establishes a claim that is supported by researched evidence and thoughtful commentary.

5.1 What does it mean to argue?

In composition, argumentation does not mean being aggressive or hostile. Rather, argumentation in the realm of academics means having a clear stance on an issue, detailing specific evidence that supports that stance, establishing common ground with others who have opposing views on that issue, and defending/explaining the advantages of that stance over the oppositions’ arguments.

5.2 Composing Strong Thesis Statements

What is a thesis statement and why is it important?

A strong thesis provides a clear representation of the writer’s stance to readers, and it also provides a litmus test for the writer while crafting the essay. All reasons and evidence should support that thesis. A solid thesis statement notifies readers of the writer’s topic and prepares readers for the argument to come. Likewise, a solid thesis statement helps focus the writer since writers can easily stray from their topics during the creation process, especially while researching for their essay; thus, a solid thesis statement also helps a writer maintain focus on the argument at hand.

What does a thesis statement look like?

Thesis statements come with two parts, a concrete and an abstract, and are usually one sentence. More simply, a thesis statement has a subject and opinion about that subject. For academic writing, the subject needs to be one of concern to a larger audience and one on which that audience has many opinions, not just two. Writers most often place thesis statements in the introductory paragraph; however, thesis statements can be placed anywhere in the essay and can even be implied.

Writing a Thesis Statement (from English Composition 1 by Lumen)

Remember your thesis should answer two simple questions: What issue are you writing about, and what is your position, or angle, on it?

A thesis statement is a single sentence (or sometimes two for long, complex essays) that provides the answers to these questions clearly and concisely. Ask yourself, “What is my paper about, exactly?” to help you develop a precise and directed thesis, not only for your reader, but for you as well.

A good thesis statement will:

- Consist of just one idea

- Make your position clear

- Be specific

- Have evidence to support it

- Be interesting

- Be written clearly

A good basic structure for a thesis statement is “they say, I say.” What is the prevailing view, and how does your position differ from it? However, avoid limiting the scope of your writing with an either/or thesis under the assumption that your view must be strictly contrary to their view.

Following are some typical thesis statements: (notice the concrete and the abstract elements in each example)

- Although many readers believe Romeo and Juliet to be a tale about the ill fate of two star-crossed lovers, it can also be read as an allegory concerning a playwright and his audience.

- The “War on Drugs” has not only failed to reduce the frequency of drug-related crimes in America but actually enhanced the popular image of dope peddlers by romanticizing them as desperate rebels fighting for a cause.

- The bulk of modern copyright law was conceived in the age of commercial printing, long before the Internet made it so easy for the public to compose and distribute its own texts. Therefore, these laws should be reviewed and revised to better accommodate modern readers and writers.

(Click here on Lumen to access more on thesis statements. )

Most Common Errors with Thesis Statements:

Too factual – Dogs have scent glands in the bottom of their paws.

Making announcements – This essay will explain why . . . ; I am going to tell you about why dogs are great pets.

Questions – Why should anyone own a dog?

Too broad – All dogs have particular personalities.

Too narrow – Barking dogs are great security.

Vague – Dogs are unique.

Examples

For other examples and more explanation, please see: TWU’s WriteSite handout

Ariel Bissett has posted a helpful YouTube video explaining the necessity of thesis statements:

YouTube Video: How To Write An Essay: Thesis Statements

In this YouTube Video from 60secondRecap, Jenny Sawyer details what makes for a mediocre thesis and what makes for a great thesis:

YourTube Video: Thesis Statements: Four Steps to a Great Essay

5.3 Developing an Argumentative Style

How does argumentation begin?

One of the best, and easiest, ways to begin argumentation is to research what others are already discussing. Just as you do not walk into a room and immediately start talking without some form of reference to the other people in that room, writers, too, need to orient themselves within a particular discourse community. What are the current topics of a particular discourse community? What are the various opinions/viewpoints

on that topic? Who are the prevalent authors on that topic? How has the conversation changed over time? Additionally, you want to remain as balanced in your argument as possible and avoid being biased. In other words, your tone and diction should be thought-provoking, but not accusatory.

Example

5.4 Analyzing Claims (i.e. Toulmin Method)

Philosopher Stephen Toulmin created a means for argument analysis, the Toulmin Model, which can also be used to create an argument of one’s own. The Toulmin Model has many levels, but the top three provide an excellent basis for both analysis and construction of an argument.

Claims, qualifiers:

Claim is similar to thesis. What is the subject (concrete) and opinion (abstract) of the author? How does the author limit (or qualify) the claim? Look for words that narrow the author’s scope, such as many, most, and some, as in “For most people, dogs make the best pets.” Analysis of a claim requires looking at the author’s intentions and scope of argument. How broadly or narrowly does the author apply the opinion? When creating an argument, qualifying the claim helps eliminate the naysayers. For the example thesis, the “For most people” helps eliminate people who live in apartments and would argue for cats.

Reasons:

What value does the author contribute to the claim? In other words, why does the author think that way? For the claim about dogs, what value do dogs have as pets? Beneficial to health and happiness, provides safety for the family, and so on.

Evidence:

What proof can be found/researched to support the claim and the reasons? Evidence comes in many forms: facts, statistics, expert testimony, charts, graphs.

What research proves that dogs provide health benefits? What expert discusses the psychological changes in people who adopt dogs? What are the statistics of home break-in’s of houses with dogs as opposed to houses without dogs?

Example

5.5 Analytical Writing

How does argument differ from analysis?

Some writing assignments ask for an analysis of a text. These types of assignments are especially popular in literature courses. Professors may ask students to analyze a short story, poem, drama, or some other type of literature, which requires a close reading of the text; however, the thesis consists of the same elements as a regular thesis, a concrete(s) and an abstract(s). In other words, specific literary elements (symbols, tone, characterization, and such) will convey some type of abstract, an opinion. For example, “In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the pentangle on Sir Gawain’s shield signifies not only the chivalric code by which he is bound, but also the levels of conflict by which he is constrained.” Concrete: the pentangle on Gawain’s shield. Abstract/Opinion: the ways that the pentangle illustrates conflicts in the story, such as man vs man (Gawain vs Green Knight) and man vs himself (Gawain’s inner struggle to adhere to the codes of Chivalry).

Analytical Thesis Statements:

To aid you in writing a thesis statement about literature, Heather Ringo and Athena Kashyap have several examples of analytical thesis statements and further suggestions on how to write them.

A strong literary thesis statement should be:

- Debatable

- Ex: “While most people reading Hamlet think he is the tragic hero, Ophelia is the real hero of the play as demonstrated through her critique of Elsinore’s court through the language of flowers.”

- This thesis takes a position. There are clearly those who could argue against this idea.

- Ex: “While most people reading Hamlet think he is the tragic hero, Ophelia is the real hero of the play as demonstrated through her critique of Elsinore’s court through the language of flowers.”

- Rooted in observations about literary devices, genres, or forms

- Ex: Hawthorne’s use of symbolism in The Scarlet Letter falters and ultimately breaks down with the introduction of the character Pearl, which shows the perceived danger of female sexuality in a puritanical society.

- Look at the text in bold. See the strong emphasis on how form (literary devices like symbolism and character) acts as a foundation for the interpretation (perceived danger of female sexuality).

- Ex: Hawthorne’s use of symbolism in The Scarlet Letter falters and ultimately breaks down with the introduction of the character Pearl, which shows the perceived danger of female sexuality in a puritanical society.

- Specific

- Ex: Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American ideals, one must leave ‘civilized’ society and go back to nature

- Through this very specific yet concise sentence, readers can anticipate the text to be examined (Huckleberry Finn), the author (Mark Twain), the literary device that will be focused upon (river and shore scenes) and what these scenes will show (true expression of American ideals can be found in nature).

- Ex: Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American ideals, one must leave ‘civilized’ society and go back to nature

(Click on LibreTexts to see more of Ringo and Kashyap’s explanation of analytical thesis statements.)

Examples

For close reading techniques for poetry and literature, please see:

For poetry analysis, ReadWriteThink offers TP-CASTT, a step-by-step close reading method. Click here to access the pdf.

Similarly, the DIDLS technique applies to analyzing other types of literature. Here’s an instructional YouTube video by Kate Mayo: How To Use the DIDLS Strategy

Here is a Google slideshow to help you analyze literature: Slideshow??????

5.6 Writing with the Appeals (see also 4.6?)

What are the appeals?

The three rhetorical appeals of ethos, logos, and pathos apply to types of responses elicited from the audience. These appeals can be found easily in commercials. Ethos appeals to a person’s sense of credibility, respect, such as Shaquille O’Neal advertising Icy Hot. An athlete of his renown obviously knows the best methods for relieving achy, sore muscles. Logos appeals to a person’s sense of logic, such as “Nine out of ten dentists choose Crest.” The nine out of ten illustrates an easy fraction/percentage (90%) of professionals who choose Crest over any other brand of toothpaste. Pathos appeals to a person’s sense of emotions, such as “Choosey mothers choose Jif.” Most parents want only the best for their children, so they will identify with being “choosey.”

Ethos: appeal to credibility

“John is a forensics and ballistics expert, working for the federal government for many years. If anyone’s qualified to determine the murder weapon, it’s him.”

“If his years as a soldier taught him anything, it’s that caution is the best policy in this sort of

situation.”

Ethos confirms the credibility of a writer or a speaker, making them trustworthy in the eyes of listeners and readers who are then persuaded by the arguments. In some cases, credibility can be established based on credentials (doctor, professor, certificate based jobs). In others, it can be determined by life experience (someone who’s mom has MS, someone who’s run a race)

Logos: appeal to logic/facts

“The data is perfectly clear: this investment has consistently turned a 20% profit year-over year, even in spite of market declines in other areas.”

“History has shown time and again that absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

Logos is used when citing facts, in addition to statistical, literal, and historical analogies. It is something through which inner thoughts are presented logically, to persuade the audience. Arguments using logos must be reliable, genuine, and in most cases, provable.

Pathos: appeal to emotion

“Where would the town be without this tradition? Ever since their forefathers landed at Plymouth Rock, they’ve celebrated Thanksgiving without fail, making more than cherished recipes. They’ve made memories.”

Writers introduce pathos in their works to touch upon the audience’s delicate senses of pity, sympathy, sorrow, and more, trying to develop an emotional connection with readers. In order to use pathos, you need to pay attention to your audience. If writing to Americans, you can use the feeling of U.S.A. patriotism. The same argument would be invalid to readers in France.

Academic audiences are primarily persuaded by ethos and logos. They want to see research from credible sources and prominent authors in their field (ethos), and they want to see accurate facts and statistics that support a claim (logos).

5.7 Alternative or Cultural Methods and Approaches

Add Carl Rogers photo

What are other means for creating argument?

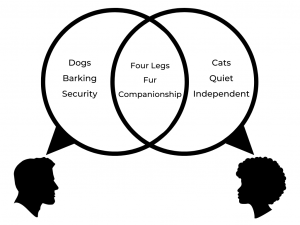

Rogerian theory suggests that the audience is more likely to listen to and be persuaded by an argument if the writer recognizes their perspectives as well. This “finding common ground” demonstrates that the writer has taken others into consideration prior to drawing his/her own conclusion. This Venn diagram illustrates two people finding common ground in the argument about dogs vs. cats:

Thus, within your body paragraphs, include counter arguments and acknowledge the merits of those arguments. Doing so will only demonstrate your understanding of the issue and strengthen your own argument. Just be sure to rebut the counterarguments by explaining the benefits of your stance over that of the counter arguments.

Examples

For more information on Rogerian, FYC at USF has posted an excellent YouTube video explaining the attributes of Rogerian Argument.

Here is a graphic organizer to help you build your argument by reacting to counter arguments: Counterargument Graphic Organizer

Another Approach to Argument:

Besides Rogerian theory, Bitzer’s Rhetorical Situation gives yet another approach to argument. Philosopher Lloyd Bitzer contends that a rhetorical situation has to have specific elements. First, a problem, a need (exigence) must require some type of discourse in order for the situation to change. Second, the audience must be people who are capable of changing the situation, not merely readers or bystanders. Additionally, constraints govern the rhetorical situation by providing specific elements, such as “beliefs, attitudes, documents, facts, traditions, images, interests, motives, . . . “ as well as elements hinging on the writer, such as “characters, logical proof, style” (Bitzer 8). According to Bitzer, these elements must be in place for a rhetorical situation to exist. Otherwise, a piece of discourse is a report or reflection or poem. Knowing the elements of the rhetorical situation helps a writer determine the topic, the audience, and the parameters of the situation, which in turn help shape the entire argument.

In The Write Place: Guides for Writing and Grammar, L. Lennie Irvin offers a thorough representations of the rhetorical situation.

The Rhetorical Situation

Although your message (thesis) may stay the same, your purpose may change depending upon your choice of audience or visa versa. Depending upon the audience, you may adjust your diction (your choice of words) or the kind of support you choose to include depending upon your audience. Writing, thus, involves many choices and a close attention to and balancing of many constraints that can shape your communication. Although Flower and Hayes presented the simple triad of goals, knowledge, and the written text as elements writers needed to balance, the following graphic depicts a more complete description these various elements and constraints of the writing situation.

Discovering and maintaining an appropriate and productive balance and alignment of these various constraints–finding one’s rhetorical stance–is one of the most challenging and important things to do as we write. We want what we write to appeal to our audience to achieve our purpose within the given context. And since we are writing for school, we importantly need our writing to fit the assignment. Finding this balance and discovering what we mean to say as well as the language to say it is not easy–and takes a process to achieve.

(To access more of L. Lennie Irvin’s The Write Place: Guides for Writing and Grammar, click here.)

Example

Wrapping Up:

Remember that an effective argument hinges on a solid thesis statement. A well-written argument establishes a clear stance on a particular  issue and defends that stance by citing relevant evidence and explaining how that evidence supports the thesis/claim. Both Toulmin and Rogerian recommend acknowledging counterarguments and then rebutting those counterarguments so as to strengthen the claim, establish the author’s ethos, and connect with the audience. More specifically, readers want to see that you are knowledgeable on the issue, that you have thoughtfully considered various perspectives, and that you have critically established your stance. Combined, all of these aspects lend to Bitzer’s rhetorical situation, the combination of problem, audience, and constraints. In a sense, argumentation entails building layers within the essay: having a solid thesis statement, relevant evidence, and thorough explanation of that evidence, which ties back to the thesis.

issue and defends that stance by citing relevant evidence and explaining how that evidence supports the thesis/claim. Both Toulmin and Rogerian recommend acknowledging counterarguments and then rebutting those counterarguments so as to strengthen the claim, establish the author’s ethos, and connect with the audience. More specifically, readers want to see that you are knowledgeable on the issue, that you have thoughtfully considered various perspectives, and that you have critically established your stance. Combined, all of these aspects lend to Bitzer’s rhetorical situation, the combination of problem, audience, and constraints. In a sense, argumentation entails building layers within the essay: having a solid thesis statement, relevant evidence, and thorough explanation of that evidence, which ties back to the thesis.

The good news about argument is, is that there is no one “correct” answer. One semester, you can argue for one stance on a topic in one course, and then the next semester argue for a completely different stance on the same topic. Readers, especially instructors, mainly want to see your ideas and reasoning more so than which stance you take. Advanced writers can defend multiple points of view by recognizing the necessary evidence to defend each stance. Knowing what evidence the opponent uses only strengthens your ability to support your own argument.

Further Reading:

Argument:

The (In)Credible Argument: Crafting and Analyzing Arguments in College, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Argument and Critical Thinking, CC BY 4.0

Writing Persuasive Sentences: