Finding Information

12 Behind the Search Lens: Effects of Search on the Individual

While search engines provide a very useful service, they have some negative impacts on both the individual user and the society as a whole. Being aware of these impacts can help us shield ourselves and those who depend on us.

Data and Privacy

Most websites, search engines and mail clients collect information about users. Most of this data is tied to the identity of the user through IP addresses. This data is then used to serve targeted advertisements and personalised content, improve the services provided and carry outmarket research. However, search engines do not always disclose all the information they collect where they collect it and what they do with that information1. Or even where they collect this information. For example, studies show that Google can track users across nearly 80% of websites2.

Information that search engines can display when someone searches for a user include:

- Information that they added in some web site,

- Information added by others with their consent,

- Information that was collected in some other context and then published on the web – by forums, event organisers, friends and others.

Information collected and processed when search engines are used include the following:

- The searched-for topic, date and time of search1,3,4.

- Activity data across apps such as email, calendar and maps, collected by search engines like Google and Microsoft3,4.

- Data bought by some search engines from third parties3,4.

- Data bought from search engines and websites that are put together and tied to the user by third parties2.

- Inferences made from the data collected.

- Inferences drawn from personal settings. For example, “to infer that a user who has strong privacy settings may have certain psychological traits, or that they may have “something to hide””5.

- User profiles or models, created by search engines, based on this information. These models are based on online data and give only a limited view of the person. Decisions based on these, when used in other contexts, will not be balanced.

Collected data on a consent-giving user can be used to draw inferences about another user who did not give consent, but who has been judged by the search engine to have a similar profile.

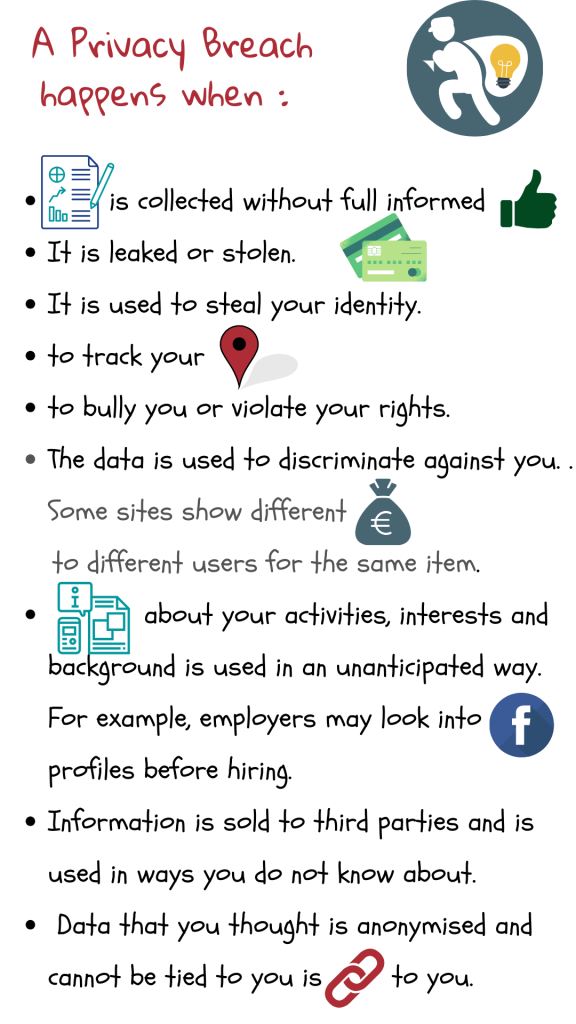

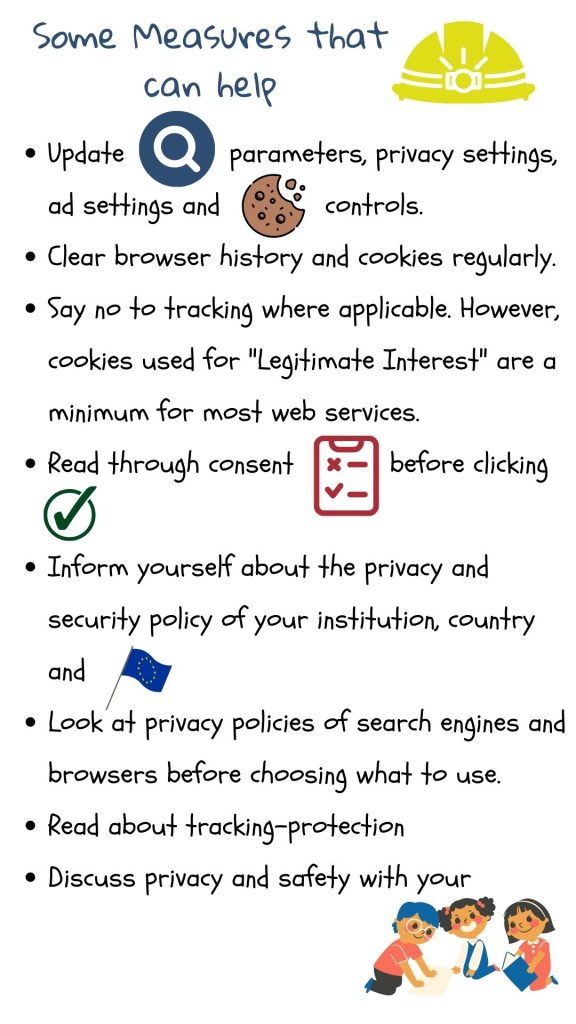

All this data, both raw and processed, gives rise to privacy and security concerns. Some measures can be taken by search providers, governments and users to prevent privacy breeches:

- Data can be stored in such a way that leaks and theft are discouraged. For example, user data can be stored in separate and decentralised databases5;

- Data is encrypted or anonymised;

- Machine learning can be used to automatically detect and classify trackers. This can then be used to improve browser privacy tools2;

- Policies and laws like GDPR legislation can introduce explicit guidelines and sanctions to regulate data collection, use and storage1;

- User-centred recommendations are made and publicised so that users, including parents and teachers, can better protect their and their wards’ privacy.

In Europe, search engine companies are viewed as ‘controllers of personal data’, as opposed to mere providers of a service. Thus, they can be held responsible and liable for the content that is accessible through their services. However, privacy laws often concern confidential and intimate data. Even harmless information about people can be mined in order to create user profiles based on implicit patterns in the data. Those profiles (whether accurate or not) can be used to make decisions affecting them1.

Also, how a law is enforced changes from country to country. According to GDPR, a person can ask a search engine company to remove a search result that concerns them. Even if the company removes it from the index in Europe, the page can still show up in results outside Europe1.

Although companies’ policies can shed light on their practices, research shows that there is often a gap between policy and its use2.

Although companies’ policies can shed light on their practices, research shows that there is often a gap between policy and its use2.

Reliability of content

Critics have pointed out that search engine companies are not fully open with why they show some sites and not others, and rank some pages higher than others1.

Ranking of search results is heavily influenced by advertisers who sponsor content. Moreover, big search engine companies provide many services other than search. Content provided by them are often boosted in the search results. In Europe, Google has been formally charged with prominently displaying its own products or services in its search returns, regardless of its merits1.

Large companies and web developers who study ranking algorithms can also influence ranking by playing on how a search engine defines popularity and authenticity of websites. Of course, the criteria judged important by search-engine programmers are themselves open to question.

This affect how reliable the search results are. It is always good to use multiple sources and multiple search engines and have a discussion about the content used in schoolwork.

Autonomy

A search engine recommends content using its ranking system. By not revealing the criteria used to select this content, it reduces user autonomy. For example, if we had known a suggested web page was sponsored, or selected based on popularity criteria we don’t identify with, we might not have chosen it. By taking away informed consent, search engines and other recommender systems have controlling influences over our behaviour.

Autonomy is having control over processes, decisions and outcomes7. It implies liberty (independence from controlling influences) and agency (capacity for intentional action)7. Systems that recommend content without explanation can encroach on users’ autonomy. They provide recommendations that nudge the users in a particular direction, by engaging them only with what they would like and by limiting the range of options to which they are exposed5.

1 Tavani, H., Zimmer, M., Search Engines and Ethics, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Fall 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta ed.

2 Englehardt, S., Narayanan, A., Online Tracking: A 1-million-site Measurement and Analysis, Extended version of paper at ACM CCS 2016.

4 Microsoft Privacy Statement.

5 Milano, S., Taddeo, M., Floridi, L. Recommender systems and their ethical challenges, AI & Soc 35, 957–967, 2020.

6 Tavani, H.T., Ethics and Technology: Controversies, Questions, and Strategies for Ethical Computing, 5th edition, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2016.

7 Hillis, K., Petit, M., Jarrett, K., Google and the Culture of Search, Routledge Taylor and Francis, 2013.