Listening, Speaking and Writing

27 Translators

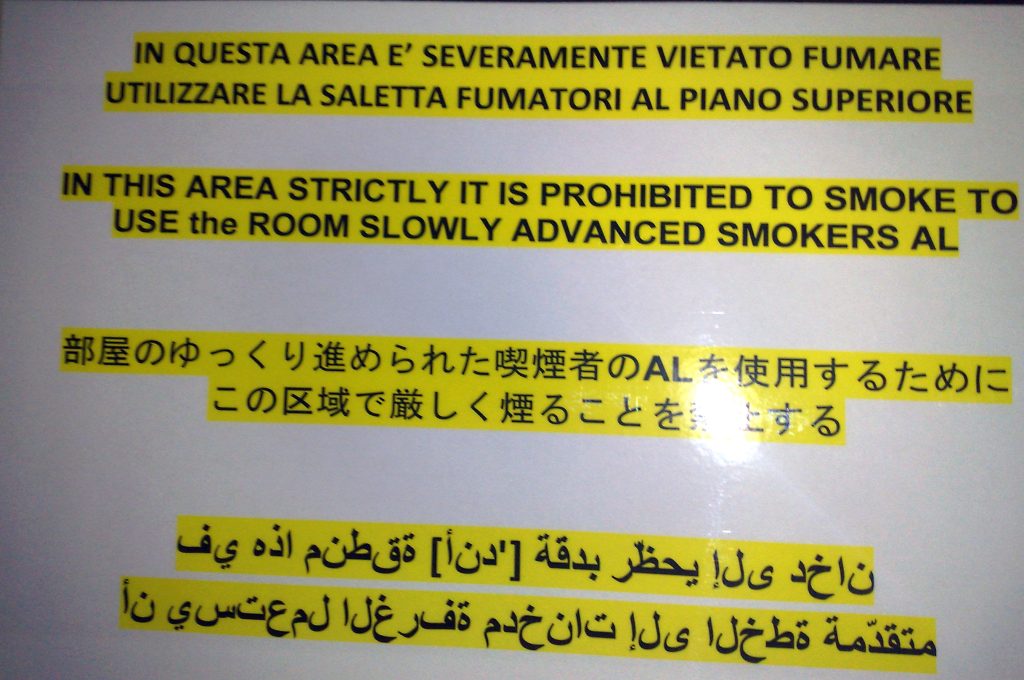

Automatic translation tools are available online and can be used in a simple way for many languages today. Some of these tools have been produced by the internet giants (Google Translate for example), but independent specialised tools such as DeepL are also available.

Historically, automatic translation has been a challenge for artificial intelligence, and the diverse AI technologies have been tested over the years. Rule-based systems (with rules hand-built by experts) were replaced by statistical machine-learning techniques when data-sets of parallel texts (the same text in multiple languages) became available. Over the past few years, deep-learning techniques have become state of the art.

Just a few years ago, you could have an enjoyable moment testing these tools, which would return amusing translations for songs or menus for example; this is no longer the case today:

- International institutions are contemplating using automatic translation tools to support multilingualism;

- Big media video platforms use automatic translation rather than human translation in order to reach more people;

- Bilingual people and translation professionals seem to use these tools both in their day-to-day lives and professional activities.

Furthermore, improvements have yet to come. The quality of translation is still improving, and solutions that combine translations with transcriptions and speech synthesis, and allow seamless multilingual communication, will soon be common.

Even if these tools have not been designed for education, they are already having an impact.

Are pupils using automatic translation?

To our knowledge, there are today (December 2022) no public official documents nor large-scale surveys measuring if this is an issue. There are discussions on forums3 and articles presenting possible ways to avoid cheating with AI, or suggesting ways to introduce AI into foreign-language classes. These assume that pupils’ usage of automatic translation tools is widespread.

We ran a smaller, informal survey in April 2022, with teachers of various languages (English, French, German) and with varying degrees of skill. The main classes corresponded to 12-16 year-old pupils. It took place in the Paris area, so pupils and teachers were French. The results were such that the teachers all had to cope with pupils who would, once out of the classroom, make use of DeepL or Google Translate.

Here are some of the remarks we got:

- The only skill the pupils seem to be acquiring is copy-pasting.

- Even the better and more motivated pupils do it – they will try to do their homework on their own, but then they will check it with an automatic translation tool. Often, they realise that the automatic result is much better than their own, so they keep the machine-built solution.

- There is a motivation issue as pupils are questioning the use of learning languages.

The above analysis needs further investigation. A generalised survey over various countries would certainly help. In the meantime, discussions with various stakeholders have allowed us to consider the following:

- Teachers can no longer assign translating text as homework. Even more creative exercises, such as writing an essay on a particular topic, can lead to using automatic translation tools – the pupil could write the essay in their own language, then translate it.

- The motivation question is critical. It is not new – in 2000, authors and educators argued that “some view the pursuit of foreign language competence as an admirable expenditure of effort; others may see it as unnecessary if an effective alternative exists”5.

Our observations coincide with reactions found in forums or reported in literature4.

Can automatic translators fool teachers?

Blog papers seem to indicate that a language teacher will recognize automatic translation, even when it has been corrected by a human at a later stage: Birdsell1 imagined a task where Japanese students were to write a 500 word essay in English. Some had to write it directly, albeit with commonly used and accepted tools (dictionaries, spelling checkers) and others would write the essay in Japanese and then translate it -using DeepL- into English. Interestingly, he found that the teachers would grade higher the students from the second group but would also be able to identify those essays written with the help of DeepL.

Can machine translation tools be combined with text generators?

These are early days to predict which will be the course of events but the answer is, for the moment, yes. As a simple example, journalists in France used a text-generator tool (Open-AI playground) to produce some text, then ran DeepL on it, and felt comfortable in presenting this text to the community2.

Is using an automatic translator cheating?

Thiscis a difficult question to answer. When consulting discussion forums on the internet3 you can easily be convinced that it is cheating. Students are told not to use these tools. They are told that if they don’t comply, they will be accused of cheating. But arguments can also be presented the other way. Education is about teaching people to use tools smartly in order to perform tasks. So how about making it possible for a pupil to learn to use the tools they will find available outside school?

This textbook is not authorised to offer a definitive answer, but we do suggest that teachers explore ways in which these tools can be used to learn languages.

What should a teacher do about this?

Florencia Henshaw discusses a number of options4, none of which seem convincing:

- Saying that AI simply doesn’t work (a favourite conclusion in forums3) is not helpful, even if pupils agree with this. They will still want to use these AI tools.

- The zero-tolerance approach relies on being able to detect the use of AI. This may be the case today1 but it is uncertain if it will remain the case. Furthermore, is using AI cheating? In what way is it different from using glasses to read better or a wheelbarrow to transport objects?

- The approach in which the tool can be part-used (to search for individual words for example) is also criticised4. Automatic translation tools work because they make use of the context. On individual (out of context) words, they will not perform any better than a dictionary.

- The approach of using the tool in an intelligent way, in and out of the classroom, is tempting but will need more work to develop activities which will be of real help in learning situations.

1 Birdsell, B. J., Student Writings with DeepL: Teacher Evaluations and Implications for Teaching, JALT2021 Reflections & new perspectives 2021.

2 Calixte, L, November 2022, https://etudiant.lefigaro.fr/article/quand-l-intelligence-artificielle-facilite-la-fraude-universitaire_463c8b8c-5459-11ed-9fee-7d1d86f23c33/.

3 Reddit discussion on automatic translation and cheating. https://www.reddit.com/r/Professors/comments/p1cjiu/foreign_language_teachers_how_do_you_deal_with/.

4 Henshaw, F. Online Translators in Language Classes: Pedagogical and Practical Considerations, The FLT MAG, 2020, https://fltmag.com/online-translators-pedagogical-practical-considerations/.

5 Cribb, V. M. (2000). Machine translation: The alternative for the 21st century? TESOL Quarterly, 34(3), 560-569. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587744.