In my 50th year, I started a project to read all of Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels, in order of publication. I’m not entirely sure why. Most men in the throes of mid-life focus on fast, fancy cars or svelte young women. But my life has always been about reading and writing, so when it comes to being crazy, this is as wild as it gets for me.

A temporary Terry Pratchett tribute graffiti that had been painted in London on Code Street, near Brick Lane in 2015 (photo courtesy of Flickr user David Skinner)

I’ve always been an obsessive/compulsive reader. When I was able to measure my years using only my fingers, it was reading the complete works of A. Conan Doyle or the entire Bible, both of which I managed in one summer. In middle school it was the entire oeuvre of Edgar Rice Burroughs, followed by Michael Moorcock, progressing to John D. MacDonald and Stephen King in high school. In college, instead of attending class like I should have, I ensconced myself in the huge University of Texas Undergraduate Library, which afforded me a massive amount of reading choices, but the one project I fixated on was the 80+ books written by P. G. Wodehouse. Returning to University a few years later (after having been politely asked to take a short break by the academic powers-that-be), my next obsession was Philip K. Dick, which my friends at the time facilitated by presenting me with a set of his complete short fiction for one birthday. A decade later, when I visited Ireland for the first time, it was sandwiched by a six-week project of working my way through James Joyce’s Ulysses with the assistance of a book of similar size that contained annotations on that work.

My name is Glen and I have a reading problem. It’s not that I read too much, but that I feel the need to read things in their complete order. As addictive habits go, I realize that this is somewhat benign (well, except for that college incident).

So why Pratchett?

It’s not like I was a particular fan of Pratchett. In fact, I was always a bit bewildered by my lack of enjoyment of the Pratchett novels that I had read. I encountered the first one, The Colour of Magic, right after it was published, but that was also around the same time as Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, to which Pratchett’s publisher tried to draw comparisons. Unfortunately, I felt it wasn’t a fair match. The concept was similar: Pratchett was skewering fantasy conventions in the same way that Adams had used for science fiction. But Adams’ book was based on a radio series and had gone through innumerable edits; frankly, the jokes were much tighter, funnier, and broad. The Colour of Magic lacked the same comic timing, relying more on repetition and incongruities that I had already seen explored in previous humorous fantasy written by Fritz Leiber and L. Sprague de Camp.

Ten years later, I tried him again. It was obvious that something was up, because he was publishing about a book a year and getting some great press. I felt I was missing out. Given that I had a smattering of Shakespeare knowledge, a friend suggested I read Witches Abroad, loosely based around King Lear. Again, I didn’t cotton to it. I got all the jokes, but nothing made me really laugh. Another decade later, I tried again, this time with Lords and Ladies, and I liked it quite a bit more than my previous attempts, and recognized that Pratchett’s prose had definitely improved over time. But I still wasn’t a fan.

Then 2016 rolled around and I felt the urge to read something, anything. I had fallen off the reading wagon around 2004 when I had been diagnosed with angina and came up against mortality, tumbling into the ditch that was video games, which provided a similar escape that fiction had fulfilled in me, but in a socially repetitive matter. I started reading again in 2008 after expatriating to Asia, but work and travel took precedent for nearly a decade and the amount I read was nowhere near the record pace of my teens and twenties. Then the end of 2015 arrived and I was living in a new location where I spent most of my daytime job-searching and worrying about employment, and I needed something light-hearted to keep my spirits up. The death of Pratchett earlier in 2015 and the numerous elegies and tributes that came out following that likely brought him to mind as the reading panacea I needed. And so, in December 2015, I re-read The Colour of Magic, then persevered through The Light Fantastic and on to the next. By Mort, the fourth book, I was hooked, and then it became an inevitable obsession following the first City Watch book. the eighth Discworld novel, Guards! Guards!

For the few of you who are unfamiliar with Pratchett’s work, the majority of it is set in a shared fantasy world that is shaped like a discus that travels through space on the backs of four immense elephants who all stand on the shell of the great turtle, A’Tuin. This is, of course, made possible by the most common element in Discworld, narrativium, otherwise known as magic. Over the course of 41 novels, a handful of short stories, and a scattering of related graphic novels and popular science explorations, Pratchett explored the nooks and crannies of this world. The first protagonist, and the least, is Rincewind, an inept wizard who is best at running away from a problem, and features prominently in the first two books, then pops up again about every eight thereafter. Other major characters include witches (Granny Weatherwax, the leader of the witches, if they had a leader, but all know that she is; Tiffany Aching, a young girl who finds witchness thrust upon her), guardsmen (Sam Vines, recovering alcoholic and defender of all citizens; Carrot Ironfoundersson, who may be the last heir of the kings of Ankh-Morpork, but was raised by dwarves and has no desire to take up the throne; Detrius the troll), other wizards (the Librarian, a wizard that was turned into an orangutan by a failed experiment but has no desire to return to being human; the blustery Mustrum Ridcully), politicians (the Patrician, or defacto dictator, of Ankh-Morpork), conmen (Moist von Lipwig, who the Patrician blackmails into first running the postal service then reforming the banking), and Death (a literal personification of the idea, black robe, scythe, and all).

Partly the reason why the first books featuring Rincewind are a poor introduction is because those rely heavily on situational humor. Rincewind constantly finds himself in the worst of all possible places and struggles to extricate himself. While there are some nice bits of wordplay in those books, that’s not the focus. I favor the novels that feature the politics of Ankh-Morpork, because in those Pratchett found his voice as a social satirist. The deftness by which the Patrician (a former assassin, and what better training for a politician?) maintains power as well as instituting progress in the city allows Pratchett to comment on our own government institutions. With each novel, Pratchett also adds a new technology or discovery into the mix, including film (Moving Pictures), music (Soul Music), newspapers (The Truth), the postal service (Going Postal), and finance (Making Money). The ongoing series about the wizards allows him to comment on universities and academics, the books about the City Watch enable commentary about law and order, and the witch novels provide a venue for an exploration of common sense and tradition.

My absolute favorite of the Discworld novels, however, is Small Gods, which stands somewhat apart from the others; the reoccurring characters are The History Monks, who only reappear in one other novel. The focus of Small Gods is on faith and belief, satirizing both clergy and followers without being heavy-handed or sacrilegious.

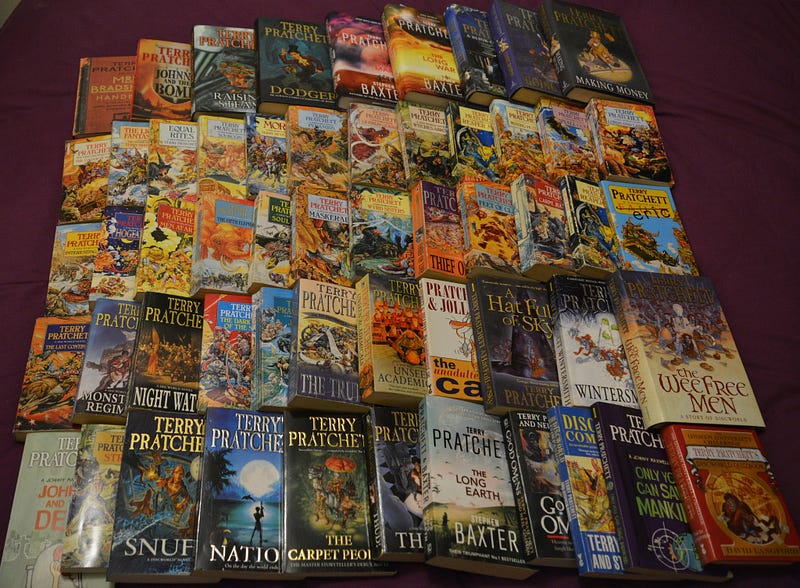

All in all, I read 36 of these novels over 2016 and was happy to have finally discovered why Pratchett had developed such a following over three decades of writing. In 2007, Pratchett was diagnosed with early on-set Alzheimer’s, which severally affected his ability to physically write, which he called “an embuggerance.” For the last eight years of his life, he continued to produce what he could, relying on an assistant who typed what he dictated. Unfortunately, the quality of his writing suffered for it, and the last five books of the series, which I have yet to read, are considered somewhat subpar to the earlier work, with more straightforward telling and less clever showing. I plan to read them eventually, just because I’m a completist, as well as someday get to Nation, a non-Discworld fantasy/alternative history, which some consider his best novel.

Most of all, though, this project helped reawaken my interest in reading and writing. It also helped that when I did finally land a new job in 2016, it was one that had a focus on writing as well. Strangely, rather than being worn out by writing during the day job, my desire to write my own work has only increased. So, thanks, Sir Terry — for a year full of laughter and discovery.