Neil Gaiman’s entry into the science fiction field was not through the normal avenues of initial short story publications in digest magazines nor paperback originals. Gaiman walks onto the stage from the world of comics, a much-maligned kingdom, often seen as solely a realm of spandex-clad heroes and talking animals. Just as science fiction has gained some respectability in the larger culture than it had in its pulp origins, comics have slowly gained a measure of value as well, due to the efforts of Alan Moore (Watchmen), Frank Miller (The Dark Knight Returns), and Neil Gaiman. Gaiman’s signature series was Sandman, which set the high watermark in comics for quality in the 1990s. Part rumination on existence, part grand unifying mythology, Sandman used the form and its tropes in new ways. It took the gore of EC Comics, the heroics of DC’s superheroes, the light fantastical touch of children’s fare, an encyclopedic knowledge of fable and fairy tales, and—Shazam!—mixed them together to show that the sum is indeed greater than the parts. The series remains in print through a collection of ten graphic novels, an almost unprecedented commercial achievement, and underscored by its critical acclaim outside of comics when a single issue (“A Midsummer Night’s Dream”) won a World Fantasy Award.

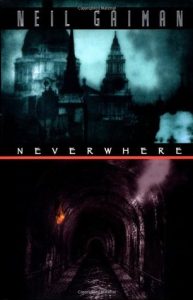

The trouble with achieving such a success is what do you do for an encore? In Gaiman’s case, the answer is to venture into new territory. While writing Sandman, Gaiman co-authored Good Omens with Terry Pratchett and published a small handful of short stories in out-of-the-way places. It was all in preparation for Neverwhere, a solo novel disconnected to everything he has done before, but infused to its core with a wealth of experience.

Neverwhere opens with two storylines: in one, we meet Door, a young girl whose family has been brutally murdered and who is on the run for her own life from the two gentlemen who seem to have been responsible; in the other, we meet Richard Mayhew, a London investment analyst whose life seems to be on the path to happily ever after. Door needs help, and she has the power to open portals to ask for assistance. In her desperation, she opens one that leaves her wounded body on a London street to be discovered by Richard, who unexpectedly deserts his fiancé on the way to an important dinner to take Door into his home to nurse her. By doing so, though, he has involved himself in Door’s troubles—into the London Below and its strange denizens—and he discovers that it is not so easy to return home.

Gaiman’s skills as a storyteller are nonpareil, yet there seems to be something strangely missing in this novel. The characters are interesting, the adventures absorbing, but one gets the strangest feeling throughout Neverwhere of deja vu. While not cliché, the settings and plot of this novel do not feel that original. The plot wherein the disenchanted modern character finds a whole new world just under the surface of his own fuels such diverse books as Michael Scott Rohan’s Chase the Morning, Clive Barker’s Cabal, and almost anything by Jonathan Carroll. The comparison with Barker is particularly apt, as Gaiman retains a certain amount of gore to counteract the fantasy adventure. As Neverwhere was originally conceived as a BBC production (which appeared in 1997), the problem may have been that Gaiman’s imagination was limited to what he could effectively portray on screen, or even that he must have felt a need to use certain familiar aspects in his desire to have the screenplay appeal to the widest possible audience. As such, the novel adaptation, while enjoyable, falls short of what we have come to expect from Gaiman.

Although he may have entered from stage left, and his first soliloquy a little flat, I still expect great things from Gaiman. He, like Clive Barker before him, seems ready-made for this new age in which words and pictures are achieving a confluence never dreamed by the Renaissance artists of the past. Working in film, graphics, theater, print, and emerging media, Gaiman is an example of the new Renaissance in our field.

[Finished 24 May 1999]