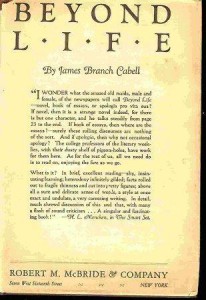

I read most of James Branch Cabell’s Beyond Life last night. I bought this book years ago because I really admire Cabell’s fantasy, his incredible vocabulary, and this was the limited edition of the Storisende collection of his work…I just couldn’t pass it up.

Cabell’s vocabulary is immense, not to mention that he was writing this in 1919 and some of his style is from a time before that. Even so, I eventually had to resort to pulling the dictionary off the shelf to refer to time and again, and it’s a rare book that I have to do that for. It’s an even rarer book that I’m willing to do it for and not, instead, just stop reading.

It’s also the first book I’ve ever had to “cut the pages” for. I knew about the practice: when you bought a book new before or around the turn of last century, often the ends of the pages were still in the “loops” of paper as they were bound into the book, and had not been sliced off by an automatic cutter. The first thing a reader has to do to read the book is take a letter opener or knife and separate the pages. The tactile sensation of engaging in this practice was almost indescrible–a combination of nostalgia (for a time when I have no reason to feel nostalgic for) or time-travel, so in contrast with today’s world of everything being as convenient as possible for the consumer.

The book itself is a series of essays about why a writer writes what they write, or at least, through Cabell’s thinly veiled stand-in Charteris, what authors should write and why. He makes a big case against the standing literary excitement of the day, realism, saying that it is impossible for a writer to truly reflect the “reality” of life (there was a line about the writer needing to put a desk on the corner of main street rather than secluding themselves in an office), and that instead the writer should not write about people “as they are, but as they ought to be.”

As he danced around this theme, he brings in the importance of alcohol to the creative imagination, using as exemplers such writers as Christopher Marlowe, William Congreve, and Richard Sheridan–who all “died” (figuratively as artists or literally) at 29, after leaving most depraved lives, but creating some amazing literature. It’s an ingenious point, and I’m not entirely sure that Cabell wasn’t putting his tongue into his cheek to tweak the puritanism of Prohibition, which he obviously didn’t care for. The funny thing about it, though, is that Cabell didn’t really start writing novels until after 29, so as an example of this, he fails utterly.

[Finished 17 November 2002]