Comics fans, as detailed in Matthew Pustz’s Comic Book Culture, have an affinity for stories that refer to other stories or acquired knowledge. In this, they resemble any number of fans of other stripes–Pustz draws a direct comparison to baseball fans and their obsessive statistics, but it’s easy to see the same dynamic at work with soap opera followers or those whose lives revolve around classic cars. Writers and artists have known this for decades, and the mainstream company’s products have reflected this through what has become known as “continuity,” which has since been as much of an albatross to the field as a life preserver.

This focus on the “in joke” built Marvel in the 1960s, who even invented a faux award for the faithful fanatics who took pains to identify continuity lapses. The “no-prize,” announced monthly in Stan Lee’s Bullpen Bulletin, was the ultimate recognition that you were part of the “in” crowd.

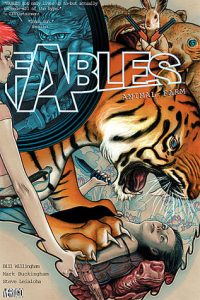

Those days are gone but the spirit remains and informs the work of two of today’s most popular creators, Alan Moore and Bill Willingham. Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen spawned a collaborative website where fans meticuously annotated his pickings from Victorian literature, later collected as a book entitled Heroes and Monsters. While Willingham’s Fables hasn’t yet been similarly honored, it is ripe for it, especially the second volume which borrows from Rudyard Kipling, George Orwell, Charles Perrault, the Bros. Grimm and other classics.

Willingham, like Moore, understands that the allusions, while possibly the seed for his imagination, have to relinquish the driver’s seat to an actual story. The in jokes never move to the back seat, though, but are a constant companion, sometimes even pointing to the route one has to take.

The basic idea of Fables: Animal Farm is derived from George Orwell’s novel, but is then twisted (as are all the characters) to fit the conceit of the series that the novels and tales of our world actually describe other realities, lands that have been invaded by the Adversary. The fables are thus refugees in our world–those who can pass as humans live in one large, TARDIS-like building in New York, while the talking animals and fantastical creatures have to stay in a magically-protected-from-prying-eyes farm upstate. Many of the animals resent this arrangemant, stating that even a velvet-lined prison is still a jail, and plan an offensive to take control of the fables’ destiny by initiating the long delayed action to retake their homes.

Aside from the simple plot resonances and pleasure of playing spot the classic character, Willingham also matches Alan Moore’s fascination for mixing his sources to find what new dimensions can be found in these familiar icons. So we get Snow White defending herself as Mowgli had to do in The Jungle Book from Shere Khan (whom she refers to at one point as “you evil fuck”). The three little pigs aren’t so little or naive, nor is Goldilocks, who, although a human, elects to stay on the farm in solidarity with the animals (or maybe it’s just that the grown up Boo Bear is simply well hung). As you can tell, this isn’t your Andrew Lang versions of these characters, sanitized and denatured for your moral edification.

The art is a perfect compliment, evoking the style of certain children’s illustrators while assisting Willingham’s prose. I’m looking forward to where Willingham plans to take this concept, and enjoyed Fables: Animal Farm as much, if not more, than the first Fables volume.

[Finished 14 August 2003]