The Fourth of July is not usually one of the holidays that is accused of being over commercialized, although the same arguments applied against Christmas, Easter and Veterans Day could easily be placed against our handling of the Fourth. Rather than being a time to reflect on the creation of our nation state, we are bombarded with sales events that promise to help us declare our independence from high prices and gaunt men dressed up as former presidents who lead the marching band to the site of a spectacular fireworks display, full of sound and fury. Education and introspection takes a backseat to marketing and entertainment. Which is why two new graphic novels, largely the home of entertainment, dealing with our national identity are welcome breezes of fresh air amidst the lingering stench of stale gunpowder. Scott McCloud’s The New Adventures of Abraham Lincoln and Steve Darnall and Alex Ross’ U.S. are quite enjoyable without delving into their polemic, but to do so is like reading Pogo and only seeing funny animals. These are books with a message, and the message is for today.

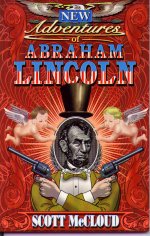

Scott McCloud is now best known for his landmark work Understanding Comics, a self-help book for the sequentially challenged. Although not as technically detailed as Will Eisner’s Comics and Sequential Art, Understanding Comics is unique in that it uses the medium which it purports to explain. It is the perfect introduction for bewildered spouses and mystified parents. Before this, McCloud was garnering acclaim for his independent comic, Zot!, a fun comic that also contained some sneaky questioning of the superhero trope and insights into the teen psyche hidden amongst its brightly colored panels. The New Adventures is also brightly colored and drawn in McCloud’s easily recognizable style — it also has teens as its viewpoint characters and their experiences are as wild and unbelievable as any in Zot! But the resemblance ends there. Zot! was an ongoing series with plots picking up and trailing away, sometimes willy nilly, as its creator battled the monthly schedule. New Adventures is self contained, with a structure and pace designed for its space of pages.

Following Understanding Comics, McCloud invested in a Macintosh, and New Adventures was done entirely through the use of the computer — in some cases creating interesting montages of scanned photos and drawn figures. In this case, as in the case of Shatter, the first comic done entirely on a computer, the artwork seems gimmicky. McCloud’s figures, in particular due to their clean lines, seem out-of-place with the highly detailed nature of scanned backgrounds. Like seeing Mickey Mouse with Gene Kelly or Roger Rabbit with Bob Hoskins, the viewer is uncomfortably aware of the differences. In the movies, the interaction between the live actors and the drawings help to bridge our suspension of disbelief; McCloud, unfortunately, doesn’t have this option.

While the art may not have been entirely successful, McCloud more than makes up for it through his story. Byron is a young boy in a high school which pays lip service to education, relying instead on rote memorization of well worn clichés. A smart reader, Byron shows a little too much initiative in history class and gets sent to detention. While there, Abraham Lincoln arrives explosively and whisks Byron off on a magic American flag tour of history. The problem, however, is that the version of history shown is as full of clichés as Byron’s class. McCloud’s message — and believe me you won’t miss it, as it permeates this graphic novel — is that slogans and blind faith were not the building blocks of our nation, yet seem to be perceived as a definition of patriotism. Instead, by using the life of Abraham Lincoln as an example, he says that history is much more rich than the prevailing clichés and that true patriotism is not blind worship of a symbol (i.e., a flag), but understanding what the symbol stands for. Yes, it has been said before, but McCloud’s method is unique and nicely done.

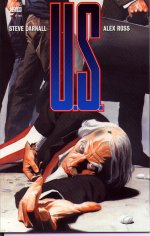

In contrast, U.S. seems much darker and pessimistic. I do not want to term McCloud frothy or frivolous, although given his light and airy artistic touch, it looks so on the surface. Just because it is drawn simply, do not assume it is simplistic. And one should not necessarily assume the reverse — sometimes the most detailed drawings belie the most banal message. Ross’ artwork is almost the antithesis of McCloud’s; instead of using computer scans, Ross paints every panel, doing figure work from photographs (a technique I associate with the Hildebrandt brothers, but which is widely utilized), creating almost Norman Rockwell-ish images. Rockwell is an apt comparison, for he was often a portrayer of the American dream, and U.S. is in many ways an update of what America is and where it is heading.

Darnall’s script starts suddenly, as we are introduced to a amnesiac street bum with a white goatee resembling the Thomas Nash portrait of Uncle Sam. Sam, as we learn to call him, doesn’t seem quite tied to the present day, and his reference point shifts back and forth from the present time to scenes of America’s past. A reader can take Sam in one of two ways; you can read him as a schizophrenic or you can see him as the embodiment of the United States. This strange juxtaposition of narrative viewpoint is often seen in prose in the works of magic realists, and Darnall succeeds with it in a comic better than I would have expected.

Like McCloud’s graphic novel, U.S. wants the reader to confront our history, to realize that times were not always as peachy keen as the school history books portray them, and that, while we may have problems in our country today, to retreat behind clichés and blind patriotism is no solution. Darnall especially wants us to take a long look at our media, and how quick sound bites make short shrift of important events. All readers will not necessarily agree with Darnall’s picture of the American past and present, but he does make one think about the subject, which is his overall objective.

Of the two graphic novels, Darnall’s is the more serious, the more personal, and the more successful. His writing and Ross’ art are quite complementary, achieving much more than either would have without the other. McCloud’s work, while interesting, fights with itself, like the horror movie in which a character tells a joke in the midst of the suspense. The combination is not always effective. Both graphic novels are worthy of attention, welcome additions to a medium too often concerned with bulging biceps and endowed bosoms rather than thoughtful commentary on the state of the union.

[Finished 1998; first published on SF Site]