When I was a child, I adored Star Trek. It ran in the afternoon opposite Dinah Shore, and I was constantly frustrated by my mother who preferred the talk show instead of Captain Kirk and the gang. Some of the first books I remember reading were James Blish’s adaptations and the fan fiction of Sondra Marshak. Our front porch was above ground with a nice railing and made for a fine Enterprise bridge in our play-acting. I used felt to cut out patches to match the emblems in the show, using the Star Fleet Technical Manual as my design guide. Yes, I was a kid trekkie.

Over the years, I have not followed the Trek franchise. Oh, I went to the movies when they came out (first one boring, second one great, third one okay, then didn’t catch the others). I tried to watch Star Trek: The Next Generation when it first came on, but it never captivated me. I went to see the first Next Generation movie, and complained for days about “the plot hole you could drive a sun through.” I’ve caught some of the other television spin-offs during hotel remote control roulette. But aside from my early saturation period, I really have let Trek go by the wayside.

So why read a Trek novel now? For years, I had heard about the Trek novel that the Trekkies hated. The one book in the franchise that would never be reprinted. It doesn’t follow the “bible,” according to one source, the bible being the all-encompassing document produced by Paramount that says what you can and can not do with the characters. Sounds interesting, I thought. I would check the used bookstore from time to time to see if they had a copy, curiosity being what it is. And I finally found a copy a couple of weeks ago.

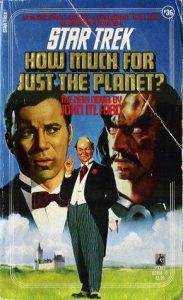

How Much for Just the Planet? pits Kirk et al. against a Klingon named Kaden and his crew in a battle for a planet in the Organian treaty zone that is a wealth of dilithium, the wonder mineral of the 25th century. Due to the terms of the treaty, both the Federation and the Klingons must show that they are the most efficient at developing the world or renounce their claim on it to the other party. The inhabitants of the world get a small say in the matter. This planet’s inhabitants try to make the most of their small say.

The book is purposely silly–the inhabitants’ actions are seen as strange by the starship crews, but this strangeness is passed over blindly (diplomats, as they are in this case, ignoring native customs that do not necessarily match their own). So when someone breaks into a song–yes, a song–the crews take it in stride, even in one case matching the operetta with a little Gilbert and Sullivan of their own (the 25th century continues its fascination with the 19th and 20th centuries–I always wondered what happened to all the musicians and novelists of the 21st through 24th centuries). There are several subplots, in which individual groups of the crews are teamed up to undergo different “movie” experiences: Kirk’s is a screwball plot (how apt, considering his way with the opposite sex); Scotty and Chekov are involved in a golf duel; McCoy and Sulu become captives of the people that time forgot; and Uhura gets to play femme fatale in a detective noir. Only Spock is left out, as he commands the ship overhead. This is wise, because his logical orientation would suffice to “destroy” the irrational illusions created by the inhabitants.

Expectations are dangerous things. There was simply no way the book could live up to its hype, and I tried to read it accordingly. While I did find some parts funny–especially Kirk in the Jimmy Stewart/Cary Grant role–on the whole it felt quite strained. Frankly, the characters are not strong enough to survive this kind of treatment, which may be the reason for Paramount’s bible. Ford does a surprisingly nice job of actually trying to contain himself to some logic of the Trek universe; I didn’t see anything here that was any more bathetic than Kirk’s pledge of allegiance at the end of the gangster episode, or the entire Eden song. Ford has gone on to much greener pastures, and probably can be thankful that this book languishes in enforced obscurity.

[Finished July 1998]