This was the overwhelming pick by First Impressions readers for the next book to read, and I was quite happy to comply. I picked up a paperback copy of The Wild Shore in 1985, then a hardback in 1990, and both copies had been hanging around my to be read shelf since then, possibly leading many another volume in their bad ways (how else to explain the sheer number of books not read?). It was quite rewarding to be able to remove it from its place of honor as the book that I have owned the longest but had not yet read.

Why is it that every post-apocalyptic book must have the same old tired plot: a youth, hearing about the grand old past, investigates and discovers the “truth” of the past? Of course, the fact is that these books, like most “non-adventure” SF, are about the present using this simplified vision of the future as a looking-glass to it. My problem with the sub-genre is that I don’t hold with the simplification–most of these books imply that our present life is “out of balance” and that, in a antediluvian world, the balance will be restored. I can hold with the former, but I disagree with the latter.

So too may Stan Robinson, if I understand the theme behind his Orange County trilogy, of which this is the first book. Taking a common starting point, Robinson looks at the world through three different fun-house mirrors, the first of which is a back-to-nature, return to the “simpler” life. This is pure conjecture on my part, not having read the other two volumes as of yet, however.

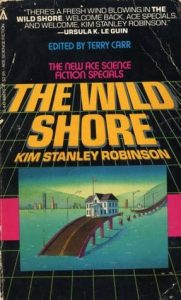

The Wild Shore was an Ace SF original, published in the same line edited by the late Terry Carr as William Gibson’s Neuromancer. While it did not set the genre on its ear as Gibson’s novel, the seeds of Robinson’s later career and his interests can be seen here. While post-apocalyptic, this novel is not a rehash of Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s A Canticle of Leibowitz–rather than concentrating on the tragedy of the apocalypse and how it might happen again and again, Robinson celebrates the enduring human spirit by attempting to show that life goes on much the same as it ever did. Parents will continue to be parents, both supporting and domineering, and children will continue to be children, full of rash actions and the naive belief that they can live forever. Like his short story, “Down and Out in the Year 2000,” The Wild Shore can be read as an answer to the cyberpunk belief that technology will reinvent the world. Robinson says, the world may change, but people will not.

As a final aside to this incoherent rambling, I was surprised early on in the novel to find another coincidental relationship between this book and Neuromancer. Much has been made of Neuromancer’s first line, which, to paraphrase, goes “The sky was the color of a television, tuned to a dead channel.” On page 34 of The Wild Shore, Robinson depicts the same color by saying, “On the coast the sky was the color of sour milk….” The two similes are one of the best indications of the different milieu depicted, and the underlying themes of both books.

[Finished 20 March 1998]