37 20th Century Compositional Techniques

By the end of the 19th century, composers began to explore various approaches to revitalize the predictability of nearly 300 years of functional harmony.

Parallelism

Music using parallel chords (parallelism) is nonfunctional and avoids the leading tone and traditional resolutions. It uses tertian harmonies, frequently tall chords, in parallel motion. The resulting parallel P5ths and P8ves are acceptable and even desirable.

Parallelism is a hallmark of Impressionism, a style of music perfected at the turn of the 20th century by Debussy and Ravel. The technique directly influenced the evolution of jazz in the early 20th century.

a. Parallelism using the major and pentatonic scales

1 and 2. Diatonic and chromatic parallelism in major employing seventh chords.

3 and 4. Parallel major chords moving along the la and mi pentatonic scales.

b. Parallelism using the whole tone scale

Impressionist composers frequently use the whole tone scale with parallel harmonies to create a floating, ambiguous sense of tonality. The lack of P5ths and half steps, and the symmetrical nature of the scale, make the whole tone scale harmonically nonfunctional. Note the free use of enharmonic spellings.

The whole tone scales generate augmented triads on every scale degree:

Augmented chords used in parallelism:

The whole tone scale provides numerous other possibilities for nonfunctional parallel harmony. The examples below show the harmonic possibilities with each of the chords available on any note of a whole tone scale.

-

- Dominant 7(

11) or enh 7(

11) or enh 7( 5)

5) - Dominant 9

- Dominant 7(

5)

5) - Dominant 9+

- Dominant 9(

11)

11)

- Dominant 7(

The example below uses the descending whole tone scale harmonized with unrelated parallel major triads.

Polychords and Polytonality

The two chords remain clearly recognizable due to their separation by range. The underlying triad or seventh chord dictates the resolution tendencies of the chord and the upper voices act as extensions (![]() 9,

9, ![]() 9, 11,

9, 11, ![]() 11, 13, and

11, 13, and ![]() 13).

13).

Polychords also may be used as unrelated coloristic devices, as in some compositions by Milhaud, Honegger, and Satie.

The melody with accompaniment below is a homophonic version of polytonality.

A related concept is the use of polymodality. The example below is a melody in A minor with an accompaniment in a somewhat modally manipulated A major. Note the parallel major chords in 10ths in the bass clef.

Pandiatonicism

Pandiatonicism was a reaction against the extreme chromaticism of late 19th and early 20th century music. Examples are found in music by Ravel, Poulenc, Copland, and Stravinsky. Chords are either tall chords (sevenths, ninths, elevenths, or thirteenths) or chords with added notes such as “add4,” “add6” or “add9.”

The example below uses a chordal texture combined with contrapuntal elements.

Pandiatonicism using parallel triads and ending with a Mixolydian cadence.

Quartal, quintal, and secundal harmony

Quartal

Quintal

Secundal

free Atonality and 12-Tone Serialism

Free Atonality

As an extension of highly chromatic late Romantic music, composers in the early 20th century, including Arnold Schoenberg and his followers Alban Berg and Anton Webern (the Second Viennese School), experimented with the avoidance of tonality.

Chords and melodies typically include smaller intervals that are “split” by minor 2nds to create the most dissonant possible sonorities:

The best way to analyze atonal music is by considering the types of intervals the composer uses to create melodies and harmonies. The limited set of intervals is called a pitch-class set or a cell, which the composer manipulates in a number of ways to generate new music, including repetition as a motive, transposition, reordering of the notes, and inversion.

To analyze a pitch class set, do the following:

- Write the pitches in order within an octave. Enharmonic pitches are considered equivalent in set theory.

- Find the ‘normal’ order by arranging the pitches within the smallest possible interval.

- Label the first note ‘0’ and the other notes by the number of half-steps over the first note. Place in brackets.

- Consider the relationships between the cells.

The above example analyzed:

Another example:

12-Tone Serialism

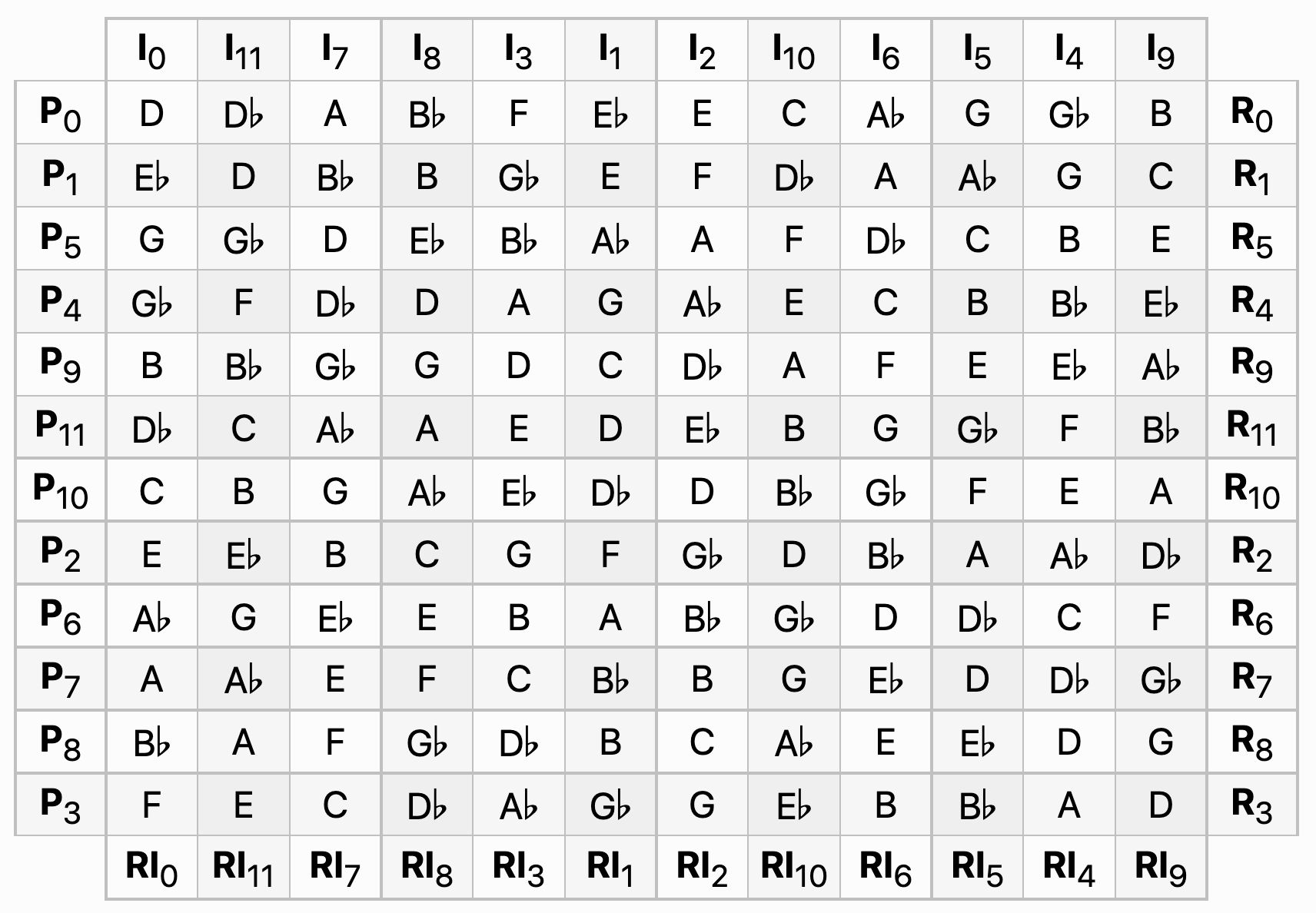

The 12-tone composer first creates a row, which ensures the avoidance of a tonal center by cycling through all 12 tones in a series. The basic series is called the prime form of the row (P). In writing a piece, composers limit themselves to the row, although they will use related rows that are generated through retrograde (R), inversion (I), or retrograde inversion (RI).

Below is an example of how the prime form can be altered to create related rows by playing the notes in reverse (retrograde), inverting the intervals (inversion), and using both processes (retrograde inversion).

In actual music, each row is presented in order. Rows can be transposed to any of the 12 pitches of the chromatic scale. Analysis of 12-tone works is done by numbering the notes of the four forms and their transposition levels, as shown above. For example: P0 = the prime form of the row without transposition; I5 = inversion of the row, transposed up by five half steps.

The tone row can be used both melodically and harmonically. Note repetitions are acceptable. Here are the same two sets as above, mixed as both melody and accompaniment:

To facilitate the use of these rows, the composer traditionally constructs a matrix. The matrix shows the notes in each row. For example, the prime (P) row in its original order (0 transposition level), or P0, is read from left to right in the first row of the matrix. The inversion transposed 5 half steps (I5) can be read from top to bottom.

To facilitate comprehension, 12-tone composers sometimes break their row into two groups of six pitches (hexachords), three groups of four pitches (tetrachords), or four groups of three pitches. The above example is based on two related hexachords.

Quarter tones

Many cultures, going all the way back to the ancient Greeks, create music using scales that include intervals smaller than minor seconds. Twentieth century composers who felt limited by the 12-note chromatic scale began experimenting with quarter tones.

Often portions of the quarter-tone scale are used within a traditional framework to provide additional color. In the mid-20th century, the quarter-tone scale was used by composers such as Györgi Ligeti and Krzystof Penderecki, who used the scale to create dense tone clusters. (A classic example is Penderecki’s Threnody, which employs quarter tones and tone clusters.)

Further subdivisions of the octave into a nontraditional number of intervals (microtones) have been employed in modern compositions since the early 1900s.

Given that most instruments are created to play the chromatic scale, extended techniques must be employed to play quarter tones on traditional instruments.

Indeterminacy

The most influential indeterminate composer is John Cage, although indeterminacy can be found in the works of other earlier 20th century composers including Charles Ives and Henry Cowell. For indeterminate composers, the definition of sound is broadened to include any type of noise. The traditional methods for notating music are insufficient; graphic scores are often used, providing general directions but allowing for the element of chance. (A classic example is John Cage’s TV Köln.) New colors and sounds are employed by performing on traditional instruments with extended techniques.

Minimalism

Minimalism was another response to the complexities of atonality. The music began in the 1960s with composers including La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass, and has continued as a viable compositional approach to this day.

One technique is to begin with an ostinato and gradually add rhythmic or melodic gestures until a complete pattern is established.

The reverse process of gradually subtracting beats from a pattern is also possible.

The example below uses an additive process that results in a rhythmic pattern that is the same as the opening rhythmic pattern, but is displaced by one eighth note.