26 APPLICATIONS

26.1. Linear regression via least-squares

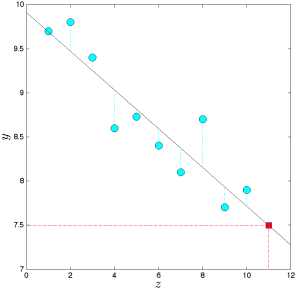

Linear regression is based on the idea of fitting a linear function through data points.

In its basic form, the problem is as follows. We are given data ![]() where

where ![]() is the ‘‘input’’ and

is the ‘‘input’’ and ![]() is the ‘‘output’’ for the

is the ‘‘output’’ for the ![]() th measurement. We seek to find a linear function

th measurement. We seek to find a linear function ![]() such that

such that ![]() are collectively close to the corresponding values

are collectively close to the corresponding values ![]() .

.

In least-squares regression, the way we evaluate how well a candidate function ![]() fits the data is via the (squared) Euclidean norm:

fits the data is via the (squared) Euclidean norm:

![]()

Since a linear function ![]() has the form

has the form ![]() for some

for some ![]() , the problem of minimizing the above criterion takes the form

, the problem of minimizing the above criterion takes the form

![]()

We can formulate this as a least-squares problem:

![]()

where

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[A=\left(\begin{array}{c} x_1^T \\ \vdots \\ x_m^T \end{array}\right)\]](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-ff92dd4466175e15383e56e7507c6d15_l3.png)

The linear regression approach can be extended to multiple dimensions, that is, to problems where the output in the above problem contains more than one dimension (see here). It can also be extended to the problem of fitting non-linear curves.

See also: The problem of Gauss.

26.2. Auto-regressive models for time-series prediction.

A popular model for the prediction of time series is based on the so-called auto-regressive model

![]()

where ![]() ‘s are constant coefficients, and

‘s are constant coefficients, and ![]() is the ‘‘memory length’’ of the model. The interpretation of the model is that the next output is a linear function of the past. Elaborate variants of auto-regressive models are widely used for the prediction of time series arising in finance and economics.

is the ‘‘memory length’’ of the model. The interpretation of the model is that the next output is a linear function of the past. Elaborate variants of auto-regressive models are widely used for the prediction of time series arising in finance and economics.

To find the coefficient vector ![]() in

in ![]() , we collect observations

, we collect observations ![]() (with

(with ![]() ) of the time series, and try to minimize the total squared error in the above equation:

) of the time series, and try to minimize the total squared error in the above equation:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \min _\theta: \sum_{t=m}^T\left(y_t-\theta_1 y_{t-1}-\ldots-\theta_m y_{t-m}\right)^2.\]](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-856407a0bc4f32663190d26954c5766e_l3.png)

This can be expressed as a linear least-squares problem, with appropriate data ![]() .

.