75 Introductions

Many writers share that they have trouble getting started writing an introduction. By the time they’ve reached the midway point of the essay, they might feel like they’re cruising toward a smooth conclusion paragraph; however, the time they spend staring at a blank page up until that midway point can feel paralyzing. To save yourself time, it’s important to clearly understand what most audiences expect to be in an introduction paragraph and to try one of these tried-and-true strategies for opening your piece.

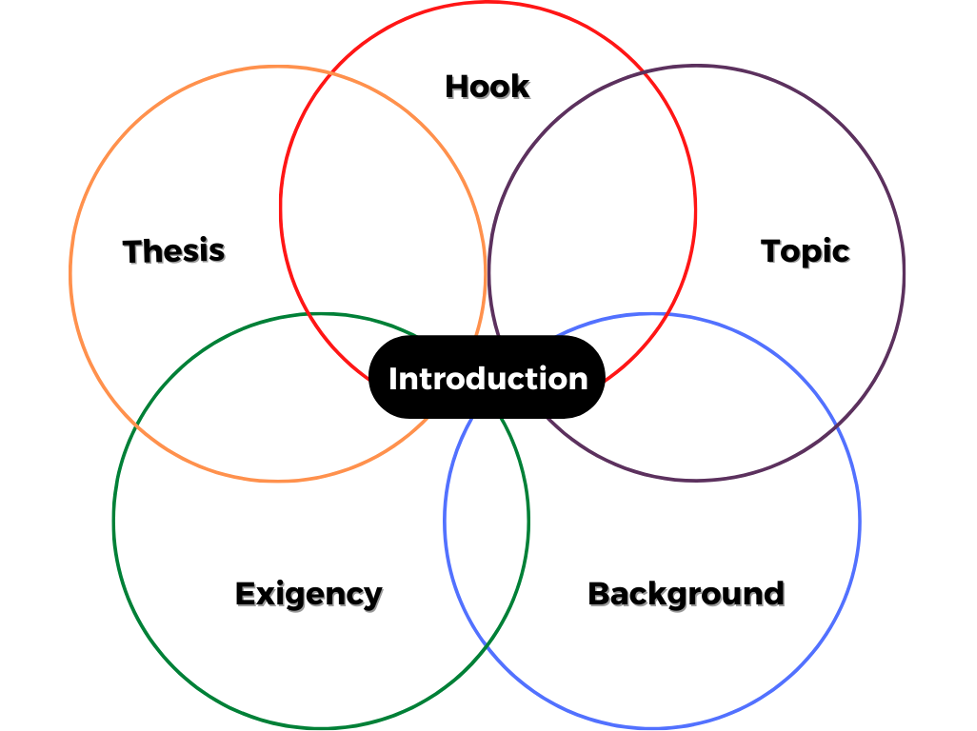

First, know that an introduction paragraph can take on many different forms. In some genres of writing, the introduction will be spread across a few short paragraphs, but in traditional academic writing it tends to be centralized into one primary paragraph at the beginning of the piece. In this first paragraph, the introduction typically begins with an attention-getting hook, a clear statement of the topic to be explored, a central message in the form of a thesis statement or tagline, any additional background information that is needed, and a sense of exigency or urgency that is invoked to make the topic appealing to the reader. Sometimes the elements needed in a solid introduction can overlap. As is the case in all writing scenarios, you should ask yourself “What does the paragraph need in order to fill in any gaps and make sense to the reader?” as opposed to “What elements of an introduction have I not included yet?” With much to consider, let’s start by covering what the elements entail.

A hook is typically the first sentence in your piece and the one that grabs the interest of the reader. Hooks come in many forms and serve various functions. To choose the right hook for your piece, you might ask yourself: “What do I want the reader to be enticed by at the start of this piece? What information would hook me if I were the reader?”

Some hooks are very direct in providing thought-provoking information while others opt for a more creative approach. For instance, it’s common for writers to begin a piece with a startling statistic or fact to entice the reader to keep reading. Occasionally, facts from history, case studies of particular people, or a relevant quotation pave the way for a smooth introduction into the topic at hand. On the flip side, creative hooks might set the scene for the reader through the development of a personal sketch, a fascinating dialogue between two people, a brief narration of a scene, a bold or shocking statement, or a thoughtful question. These are just a few strategies to consider when deciding how to hook your reader.

After you’ve hooked your reader, you will want to provide enough background information on the topic in order to help the reader understand the focus of the piece. For example, you might be writing a paper on a dangerous cult leader, and so the initial background information you provide can offer the reader specific context that is essential to understanding the focus of the piece. In journalism, a funny term for providing such context is the “nut graf” or “nut graph,” which is a sentence or two detailing the most important facts of the story. To write out these contextually rich sentences, consider using the 5 Ws + 1 H heuristic, which involves asking yourself what the who, what, where, when, why, and how of the piece is? In this cult leader context, you might ask yourself:

Who is the cult leader?

What cult did they lead?

Where did the cult form?

When did the cult form?

Why did the cult end?

And how did the cult function in society?

After answering those questions, I might respond with the following nut graf:

David Koresh led the Branch Davidians, a religious cult located outside of Waco, Texas, which ended when authorities from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms raided the cult’s facilities in 1993.

Notice how every question that was originally posed can be answered by the statement above. It’s relatively simple and straightforward, and yet lots of necessary information is packed into one sentence so that the introductory paragraph isn’t overly long.

You can read more about thesis statements in Chapter 4, and you might consider how thesis statements can augment a sense of exigency, or the feeling that you need to become involved in or take immediate action in response to an issue, event, or crisis. A first paragraph introducing a 1990s religious cult might not seem like a timely topic that people need to take action on. However, if you remind readers that history can repeat itself and religious or political zealots must always be kept in check, then you will build a sense of exigency that will motivate your reader to keep reading into the body paragraphs.

It’s worth noting that not all writers compose their introduction paragraphs first. In fact, some writing teachers insist that the best way to get started is to begin writing out your body paragraphs first, and once you know what the bulk of your paper will cover, you can write the introduction paragraph last. One of the biggest benefits of this approach is that you won’t spend too much time toiling over an introductory paragraph that you’ll want to change later because it doesn’t represent how fruitfully your ideas evolved through the process of writing. Although this approach doesn’t work for everyone beginning a new draft, this approach can be helpful later in the writing process, too. That is, if you begin your composing of a piece by writing the introduction paragraph first and your body paragraphs later, consider rereading and revising your introduction to ensure that it accurately reflects what follows in the subsequent paragraphs.