89 Revising

Even the most experienced, successful writers may cringe a little at this stage in the process. But there are good reasons to enjoy it, or at least, embrace it. First and foremost is that the revision stage means you’ve written something; now it just needs polishing. To get started, think of it as re-vision—literally, seeing your piece again from a different angle. That is, in revision, you reimagine your work and its potential. Consider the following questions, which can help guide and focus your revision, especially if you get stuck and aren’t sure how to move forward.

- What new information can you discover as you revise?

- How can you add new information to what you’ve already written?

- What challenges did you encounter, and how might you respond to those challenges in writing to strengthen the piece?

- What linguistic, rhetorical, design, or other devices can you experiment with to impress and engage your reader?

Before you can ask these questions, however, you need to have written your first draft; you need something substantive to work with. As Jodi Picoult, a successful American novelist, says, “You can’t edit a blank page” (Kramer). Another writer, Anne Lamott, reminds us that early drafts aren’t perfect. These points are both spot-on. You need a working draft for revision, even if that draft is far from perfect.

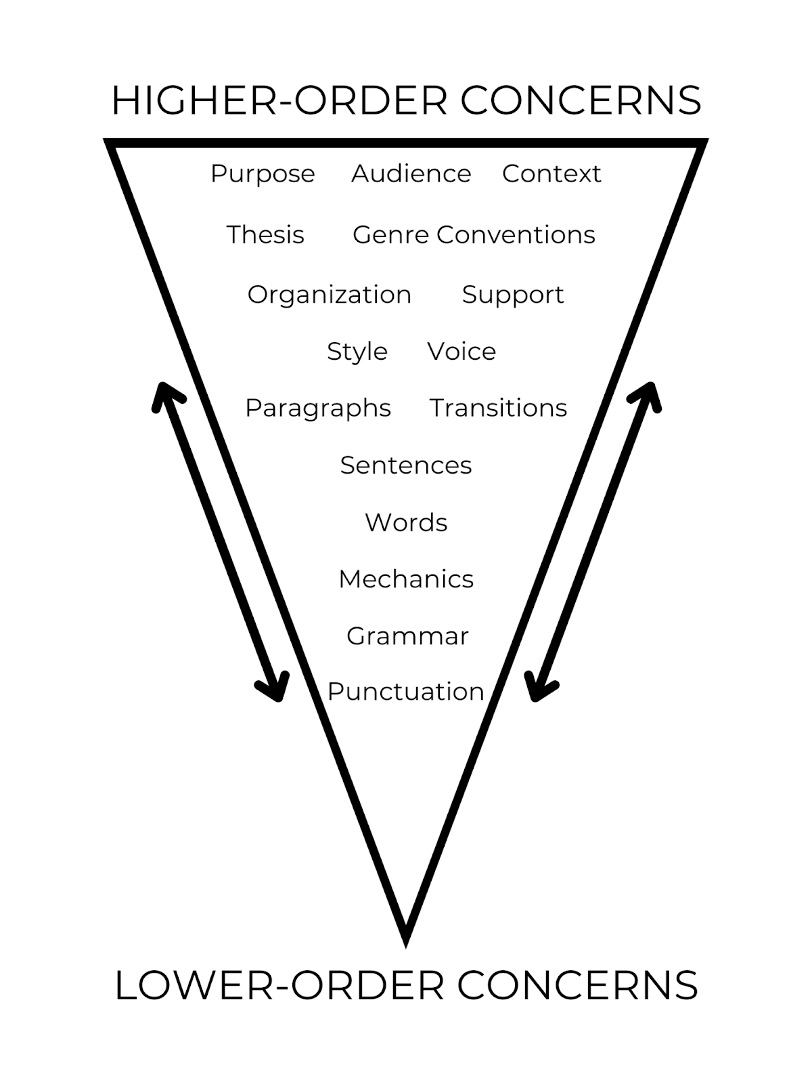

Furthermore, revision is more than just editing or proofreading; revision requires critical thinking, feedback, and a careful examination of our work. Note that we said examination. Revision is not a quick scan of your work for errors like comma problems, misspelled words, or other low-order concerns (LOCs). That’s editing and proofreading. Revision means looking at your work as a whole, taking notes of all its parts, their overall effectiveness, and other HOCs.

Revision, in other words, means examining such concerns as organization, argument/thesis, purpose, audience, and supporting evidence. It is difficult, if not impossible, to revise without considering these components, which we call higher-order concerns (HOCs) because these components have a bigger impact on the overall effectiveness of any composition. Lower-order concerns or LOCs, on the other hand, affect the overall appearance, polish, and clarity of the composition.

In this chart, the most significant HOCs are purpose, audience, and context; as outlined in the chapter on rhetoric, these three form the rhetorical situation. It’s critical to make sure these elements (purpose, audience, and context) are clear and effective. Of nearly equal importance are the thesis or argument and genre conventions.

To consider these concepts in action, imagine you’ve written a visual analysis, and you’re trying to decide which HOCs to prioritize. In the visual-analysis genre, a reader would expect to read 1) a description of the artifact you’re analyzing; 2) a clear identification of its key components; 3) a detailed description of how those key components work together to accomplish the overall purpose and message of the visual; and 4) an evaluation of whether those components work well or not and why or why not. Therefore, when you start revising, step back and think about a) your purpose, which is to breakdown the components to properly evaluate the visual; b) the artifact’s intended audience as well as the audience you’re relaying your analysis to; and c) the artifact’s context and the setting for your analysis. These are all HOCs. If your HOCs are all aligned with the purpose of your piece of writing, then you may be close to finished with revising. If not, then you may need to revise further.

Revision, therefore, is an important stage in the writing process. It takes time and persistence. If revising feels like an extra step that you don’t have time for, take a cue from the best writers. Professional writers, for example, understand that developing good revision habits will strengthen their communication skills in the long term and for each individual project. Therefore, they budget their time to allow for revising. With practice, revising gets easier. Furthermore, remember that writing is a recursive process; you can revisit earlier steps in your process before, during, and after revising. In the end, however, revision helps us develop effective writing habits. Revision also helps us understand ourselves as writers and communicators by providing an opportunity to reflect on our purpose in writing how well we achieve our purpose. Therefore, plan to make revision a central part of your writing process every time you write.