84 Planning

Do you like to plan your trip or just explore? Many writers like to plan their work before getting started. Like a roadmap, however, a writing plan doesn’t have to be an outline. Planning can take on the form of clustering, mind mapping, or flowcharting.

The two-part goal of these planning activities is 1) to get your ideas out of your head and into print, and 2) to launch you into the beginnings of a good plan, organization, sequence, or other kind of order. Whether you cluster or outline, all of these approaches work like a roadmap or list of places you’re going to visit with your audience so that they will, hopefully, arrive at the destination you have in mind.

For example, when you load an address into a map app, the program lays out a sequence of turns, distances, alternative routes, roadblocks, coffee shops, gas stations, and so forth. All of these places are, potentially, notable places on your way from point A to point Z. The map app also includes a “Start” button or “Begin Navigation” command. When you use voice navigation, the app gives vocal directions such as “In 400 feet, turn right on Main Street. Your destination will be on the left.”

That’s what plans do: They lay out the directions, distances, meaningful landmarks, and the end point. For writing, read on for a few common ways to plan your trip.

Clustering and Mind Maps

Some writers like to draw or sketch out their ideas. In clustering, for example, you write a key idea in the middle of a page; circle it; then fill the page with related ideas and words; circle each idea or word individually; and draw lines connecting new ideas to the original idea.

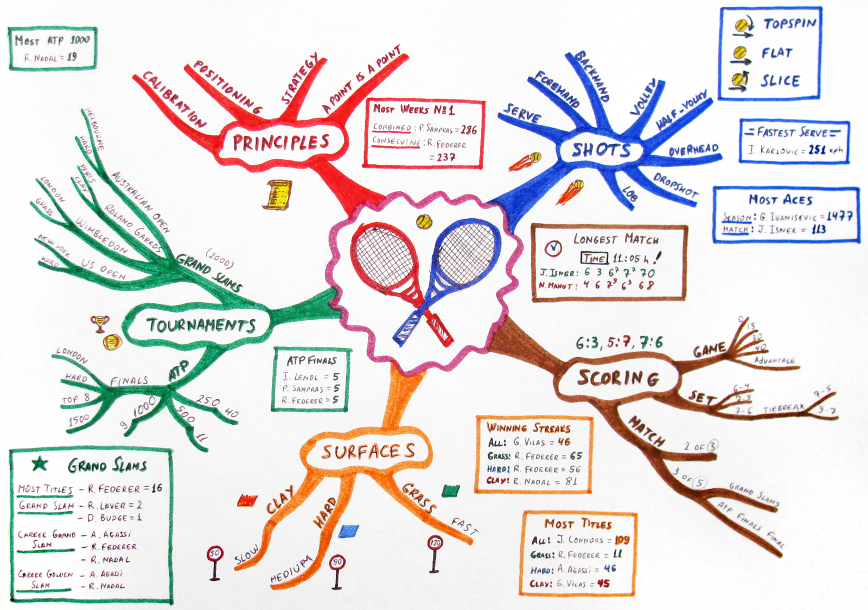

A similar visual approach is a mind map, which you can do by hand or complete with a digital application such as Mindly and Ayoa. Like clustering, flowcharting, and tree diagrams, mind maps help you discover connections between the ideas you have for your work. The following image depicts a mind/cluster map at work to help a writer organize and structure their report on tennis.

Flowcharts

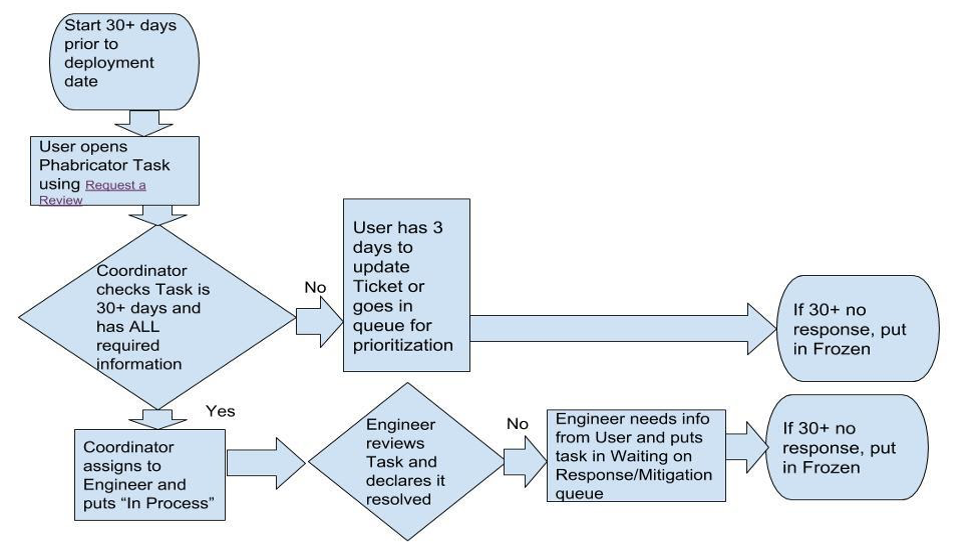

This type of planning typically starts with a big idea or title or a simple “Start here!” From there, most flowcharts move through key topics or points as if you’re playing a board game. The last point on the chart shows the destination or conclusion. The example shown below displays the writer’s process for developing company policy. Notice how the writer moves through different stages and actions before coming to the final decision and action. Flowcharts can help you find direction and see how things fit together.

Outlining

More formal than the planning activities listed so far, outlines break your project into parts, levels, or sections: A, B, C, D, E or 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 (or whatever ordering system you prefer, from bullet-point lists to stars). You can write out full sentences for each part or use short descriptions. A basic outline for this section, for example, was follows:

- Beginning

- Introduce planning

- Provide context

- Define terms

- Middle

- Clustering & mind mapping

- Flowcharting

- Outlining

- Conclusion

- Restate key points

- Provide closing guidance

From the basic 1-2-3 or beginning-middle-conclusion approach, start filling in the details. What do you need to do in the beginning? Typically, introduce your topic and, if possible, state your key point or argument (often called the thesis statement). In the middle, it’s common to provide several examples or other forms of evidence that support your point. In the ending, you need to sum up those points, tie everything together, or come to the resolution of the story. By the way, some writers use full sentences in their outlines; others break the plan into bullet points. It’s up to you!

As we’ve explored here, there are so many ways to plan your writing project, from clustering to outlining. Each approach prepares you for the work ahead, helping you plot your course, manage your time, gather information, and start writing your first drafts. Another key point is that at any planning stage (and any point in your writing process, really), writers often return to the brainstorming step or sidetrack to do more research or revise their outline. Remember, too, that the writing process is recursive; it’s okay to mix-and-match your way through the work. Therefore, feel free to return to any of these planning steps as needed. Also, if you sense that your plan isn’t working, try reverse outlining. Once you’ve launched forward with your work, keep moving.

Attributions

“Processes Flowchart,” CPortero (WMF), CC-SA 4.0, https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Processes_Flowchart.jpg.

“Tennis mind map,” http://mindmapping.bg, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tennis-mindmap.png.