83 Prewriting

As the name suggests, prewriting comes first. Brainstorming, listing, asking questions, freewriting, and looping are common activities at this stage, though you can use them at any point in your process. That is, you can repeat or retrace these steps at any point in your writing process. The goal is to take these first steps for your writing journey, like doing warm-up stretches before karate or yoga class.

Brainstorming

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines brainstorming as “the mulling over of ideas by one or more individuals in an attempt to devise or find a solution to a problem.” On your own or with a group, brainstorming means generating ideas informally and without the pressure of finding the “perfect” solution or direction. This activity takes a variety of forms for collecting the ideas you come up with: cluster maps, flow charts, Venn diagrams, and so forth. A few neat tools for these activities are MindMeister, Popplet, IdeaBoardz, SimpleMind (mobile app), and Ideament (mobile app), but there are plenty more to explore. Of course, there’s always your good ol’ paper and pen(cil) for jotting ideas on a whiteboard as they pop into your head or folks in your group share their ideas aloud.Whatever approach works for you, brainstorming is vital to the writing process because it helps get those gears turning and our thoughts organized.

Guess what else is neat about brainstorming? While it’s often pursued as a prewriting activity, you can brainstorm in the middle of your project or near the end, too, especially when we’re not sure where to go next or what to do. For instance, when we come across that ever so difficult and paralyzing feeling of writer’s block, guess what? Brainstorming can get us moving again. After all, writer-teacher Donald Murray says that writer’s block “is a natural and appropriate way to respond to a writing task or a new stage in the writing process” (1985, p. 44). In other words, it’s okay to get stuck. Take a deep breath and try brainstorming or another low-pressure activity, such as freewriting, clustering, or looping. In the same way the air typically feels fresher, clearer, and promising after a storm, after you brainstorm, your mind may feel refreshed, clear, and ready to get going and produce amazing ideas for writing again.

For a fun take on brainstorming, see this video, in which comedian and producer Bernie Mac talks about his creative process.

Listing

This activity is a kind of brainstorming in which you or your team list possible topics, examples, directions, and big ideas (little ones, too). Listing resembles outlining but is less formal and less structured than an outline might be. As with other activities in this section, the goal is to get your ideas flowing and to start writing.

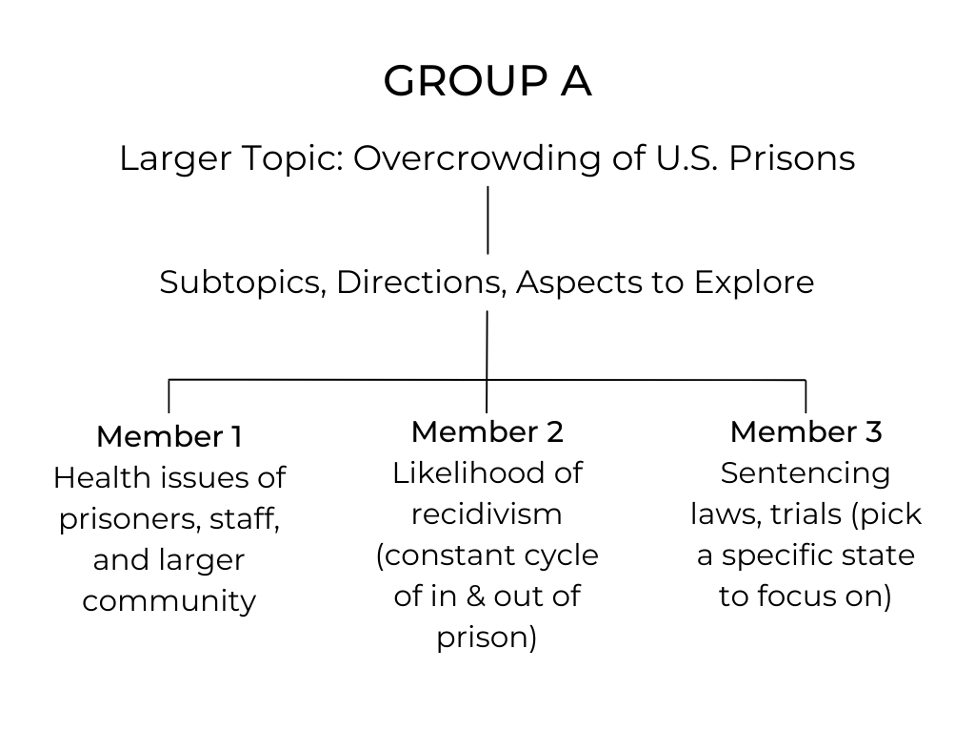

Here’s a list about the Overcrowding of U.S. Prisons, done in a structured variation called a tree diagram or organization chart.

Freewriting and Freetalking

This activity is one of the most unstructured, because it entails writing without worrying about pesky grammar, perfect outlines, or great ideas for the direction of your paper. Freewriting is usually completed in short bursts and is most helpful after brainstorming or listing. For example, look at your brainstorming notes or lists. Then, for 5 minutes, 10 minutes, or 15 minutes, just write whatever comes to mind without judging, editing, or self-censoring what you’re writing.

You may also find it useful to try freetalking, which is free-association style talking, which happens when you think out loud, recording your thoughts in a brief audio recording or while talking with a classmate who takes notes on what you say. Whatever approach works for you, freewriting and freetalking don’t require solid directions or perfectly composed sentences; you’re just thinking through things. Do, however, pause periodically. Read what you’ve written so far,listen to what you recorded, or ask your listener to repeat back to you what they’ve heard you say. Pick out one good or intriguing sentence or idea; write it down and try the next activity.

Looping

What do you do when you get stuck in traffic? Look for alternative routes. When there are none (or the next exit is a mile away or more), perhaps you turn on some loud happy music for a calming brain-break. Like searching for alternative routes or switching to a low-stress activity, a useful technique in your writing repertoire could be looping, a focused or structured approach to freewriting. For example, here’s a useful exercise, adapted from The St. Martin’s Guide to Writing:

- On a piece of paper, in a new Google Doc, or wherever you prefer writing, jot down your topic or idea. Take a moment to read what you wrote.

- Set a timer for 5 or 10 minutes (your choice), and then write without stopping.

- When the timer goes off, stop!

- Read what you’ve written so far. Highlight or underline the best sentence, idea, or other point.

- On a new page, rewrite your topic/idea. Add one of the sentences or key points you marked in step 4.

- Set a timer and write nonstop again for 5 to 10 minutes.

- Repeat until you have a better sense of the direction you want to take next.

Asking questions

Another prewriting activity is asking questions. By creating questions and trying to answer them, you gain a strong sense of direction by engaging in inquiry which can be especially helpful because writing can be daunting. The questions to ask can vary from writing project to writing project, of course.

For a research paper, you might ask:

- What do I know about my topic?

- What do I want/need to know about my topic?

- What does my audience want or need to know?

For a narrative essay, you might ask:

- What idea or event has been meaningful to me?

- What story might I want to tell about that meaningful idea or event?

- What story might I want to tell other people?

- What stories do I like to hear and why do they resonate with me?

- How can I tell a story my readers will be able to connect to?

Questions like these can help you prioritize directions and content. It’s also helpful to ask a peer or peer group a few questions after sharing some or all of your work with them. Often in such conversations, we can sort out our thoughts and even get some good ideas. If you like, flip ahead to the peer review section; there are some good questions there. You may also find the next exercise helpful.

Analysis Essay Prewriting

Analysis prompts you to take a deeper look at what’s in front of you by breaking a text down into smaller components in order to better understand how various elements interact to send a particular message to an audience. Below are five questions to help you get started writing your analysis essay.

- A question that prompts a closer look: what is an important question you have about this text and its presentation?

- A description of the subject you are analyzing: what is the context for this text? What various elements catch your attention first, second, and third?

- Evidence drawn from close examination: what textual evidence might support your analysis of various elements that stand out to you?

- Insight gained from your analysis: how do you understand the subject of the text differently after having paid close attention to particular elements and components? How specifically can this text be criticized or praised?

- Clear, precise language: what are the key terms that need to be defined for any reader to understand this text and your analysis of it?

Repeating Steps

Remember: You can backtrack, sidetrack, and get back on track at any point during the writing process. It’s also okay to skip ahead; many writers jump to working on their conclusions, then return to the introduction later. An option, therefore, is to return to, or skip ahead to, any other step in the writing process when needed. Once you’ve completed a first draft, for example, ask yourself a few questions. Would a fresh round of brainstorming help? Is it a good time to talk about your work with a colleague or read passages aloud? Perhaps you need more information from other sources or need to read a model essay in the genre. Of course, you may need a break from writing (which we all do at times). Maybe you need feedback on what you’ve done (or thought about) so far. Just remember to come back and do what Butler said: “Keep writing.” And guess what? All the activities we’ve discussed so far are writing.

There’s one other possible step here, of course: If you’re truly stuck, the project just isn’t going the way you want it to, or it feels as if you’ve hit a dead end, even the most experienced writers will scrap what they’ve written to start over. Have you ever started a road trip and decided you didn’t want to go to, say, Main Street after all? Dead ends happen in writing, too. We highly recommend, however, that you talk with your instructor if you hit such a road block.