1

The Graphic Design E-Learning Checklist is intended to help educators design intentionally in a way that is digitally accessible and visually appealing. There are two parts to the Graphic Design E-Learning Checklist. The first part is all about digital accessibility.

This digital accessibility section of the checklist has the following categories:

- Alt Text

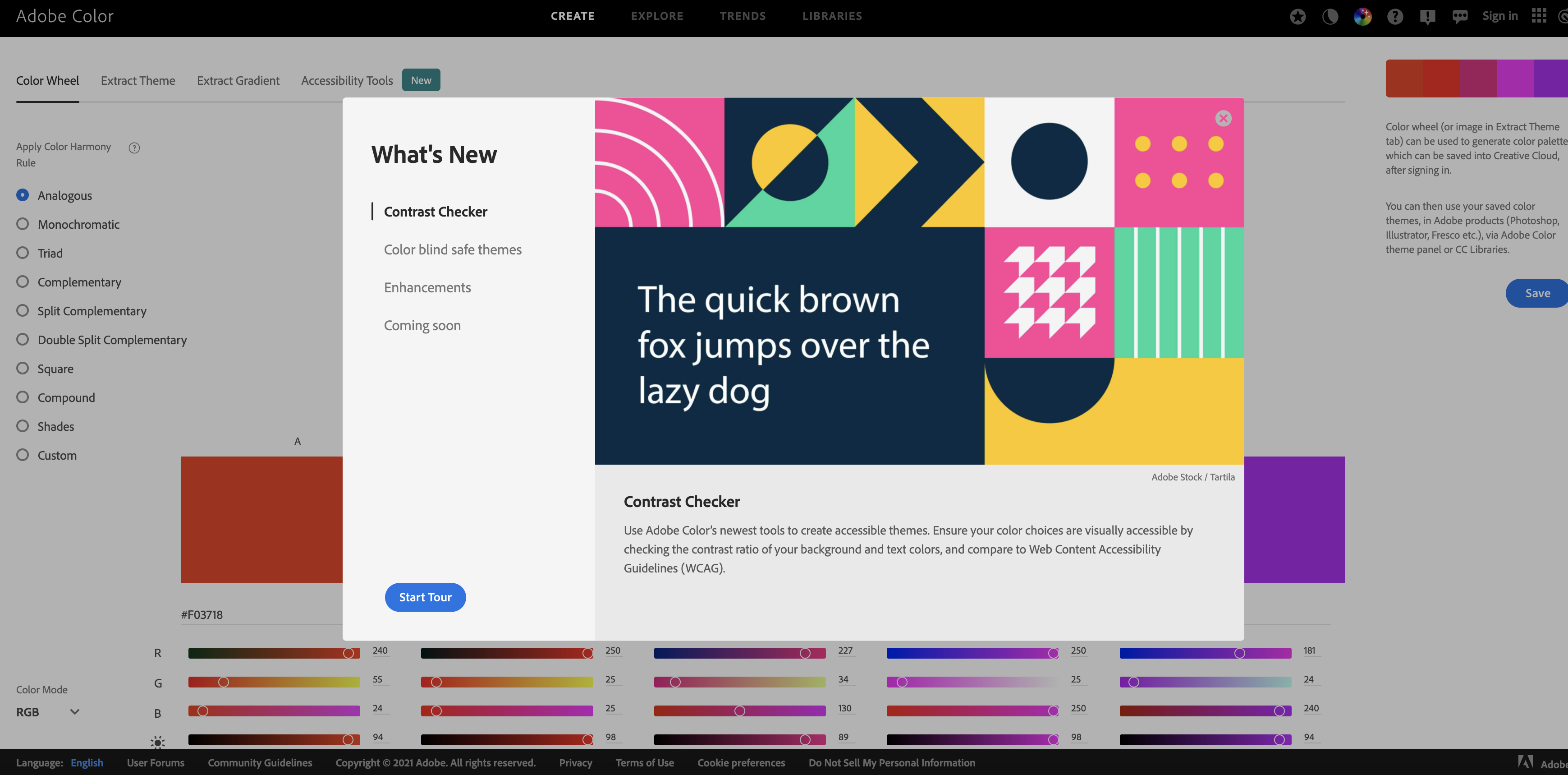

- Color Contrast

- Headings

- Links

- Lists

- Video

When course creators aim for accessibility, they should first define their goals, analyze their stakeholder needs, get organizational buy-in and then start out small, revising, designing, and reiterating with learners of various abilities to beta test the designs. If course creators make strides to improve their practice to consider inclusive opportunities, they can make progress toward a more digitally accessible world. This Graphic Design E-Learning Checklist is not intended for designers to reach 100% accessibility every time, but the checklist contains some major items to consider. If you want to learn more about digital accessibility there are resources provided in each corresponding section of the book. The digital accessibility section comes first because we need to think about how to design learning to be inclusive at the forefront rather than trying to fix everything at the end. In 2021 WebAim conducted an analysis of the top one million web pages and found that 97.4% of the homepages had WCAG 2.0 errors. The areas of concern that are also covered in this book were low contrast text (86.3% failing), missing alternative text for images (60.6% failing), and empty links (51% failing). We can do our part to help improve these percentages. Our goal is to enhance these areas but it is important to note that the digital accessibility section of the checklist does not guarantee 100% compliance with any government or regulatory agencies in any country.

The second part of the Graphic Design E-Learning Checklist is about graphic design theory.

It contains the following categories:

- Contrast

- Repetition

- Alignment

- Proximity

- Color psychology

- Typography

- Minimalism

The Graphic Design E-Learning Checklist will help course creators to design learning that sticks. When you use graphic-design theory correctly, you reduce cognitive load. This means the user has less friction or fewer barriers as they take the course because they do not have to struggle to decode the content on the page. Some of the above principles are part of the author Robin Williams’ core principles from her book Non-Designers Design Book, but written through the lens of e-learning and course design. The goal of this section is twofold. First, it will help you create visually appealing portfolio pieces that will raise the caliber of your designs, help you attract better-paying clients and perhaps even land you your first instructional design job. People who have visual design skills have polished-looking e-learning and courses that show an advanced level of skill and understanding about brands, the learner persona, and how design can help communicate content visually.

White space, easy-to-read typography, intentionally-selected images that help break up the text, and strong color theory aid in cognition and make learning more likely to be remembered over time. Since the digital accessibility section comes first, you will already have an idea of how to design with fewer barriers. But, with the added ideas in the graphic design section, you will be able to create items that are not only accessible but also beautiful. You may be wondering how to get started and how to apply both these concepts at once. Designers work in different ways. You may want to design for both simultaneously or one at a time. Initially, you may choose to select an accessible default font and black-and-white only in your prototype, just blocking in some of the text and images. So, when you come to the graphic-design section, you can start to be more daring with the choice of color and text, cross-checking back to the digital accessibility section to make sure it works.

When I design, I use prototyping in the form of mockups to ensure that I don’t go too deep into a design or concept without client approval. I will sometimes show a portion of a design project and then offer a few versions of only a small section of the course or learning. I often do a font exploratory and a color exploratory before I commit the choices to the entire project. A font exploratory is a sheet of different fonts mocked up in a few words and/or phrases for the purpose of selecting the best ones. The color exploratory works in a few ways, usually I will mock up a design and offer the same design in multiple color combinations – one on each page so that the client can select the color story that resonates the best. I only offer choices that I can get behind in terms of emotional and digital accessibility. In other words, when I present my ideas, I do so in a way that I back up my choices with sound graphic design theory, color and type psychology, multimedia principles, and digital accessibility standards. This usually helps with client/institution buy-in.

If you work in higher ed, you will find that the field is particularly fond of data-informed, empirically sound decision making which means you may be tapping into some academic journal articles when explaining design rationale. For corporate clients, the decision of “look and feel” may be more nuanced. Branding needs to be considered in more depth and companies may rule out certain decisions if they don’t feel it is in line with their positioning or attracts their target audience. Or, maybe they just don’t like a specific color or color combination for a personal reason. Offering a few choices and compromising will get you far.

I recall a freelance client I had many years ago. A friend of mine recommended my services to an up-and-coming real estate agent. This client was going out on his own and starting a new agency. He wanted me to help him create a corporate identity system, which included a new logo, signage, and apparel. I clearly remember our conversation like it was yesterday. We were sitting at a coffee shop as we freelancers often do and he began to explain what he was looking for.

“I want to launch my brand and I want it to be red and yellow. I love the branding of Mcdonald’s. It’s bright and happy and it stands out from the road. I want my sign to do the same,” he said.

“I understand you want people to see the signs on lawns, the sign on your office, and the like. That makes sense. We can still create a high-contrast logo even if we don’t do red and yellow. Red and yellow psychologically make you hungry, they are often used in tandem in the fast-food industry and they may not be the best choice for a professional-looking real estate firm. Can I convince you to look at any other combinations?”

“No. I love these colors. My mom loved these colors too. I really don’t want to budge.” His posture grew rigid.

“Ok. Got it.” I said.

I then went home and got to work. First, I showed him some black and white images, to nail the concept. Doing this allows the client to stop thinking about color and focus on the design. I then did a font exploratory to look at the logo in different typefaces. It wasn’t until the final iteration that I introduced his had-to-have red and yellow combos. We met again at the same coffee shop a few weeks later when I unveiled the color logo choices.

“OK. I did your logo in red and yellow as you asked, but I also did a combination in a slightly different way. I took the red and I deepened it to a maroon, then I made the yellow more of a gold. This made it more regal but still kept the contrast high. The gold is light, the maroon is dark and it’s easy to see these as signs from the road. It looks high-end, sophisticated, and professional. Here is the difference between this color combo and the bright red and yellow combination,” I said then held my breath while I gauged his response.

He proceeded to flip back and forth between the two choices. “Hmmm. MMMM Hmmmmm. Huh? Hmmmmm.” His brow furrowed.

He finally looked up and said “I like it, sold. I am glad you showed me this and I appreciate you using my suggestion but you took it to a whole new level. Thank you.”

I breathed a sigh of relief.

You see, designers are change agents. They often have to rally for change, stand fast in their opinions, and consider the stakeholders at all times. We must think of emotional and digital accessibility and we have to hold our clients/SME’s hands sometimes when we guide them over the threshold. I find it is easier to convince others to improve their digital accessibility measures than their graphic design skills, but both are important. If you find you are getting pushback on the digital accessibility efforts, I like to remind clients who don’t think that is important that lawsuits could occur. In many industries, there is a legal minimum accessibility requirement, so the failure to meet that could make for dire consequences. For clients who appear to lack empathy, this approach to change management may be needed.

The Graphic Design E-Learning Checklist in two parts

The Graphic Design E-Learning Checklist is located at the end of the book, but you will see portions of it as you make your way through the relevant sections. We want to review the checklist in order but we can always check back at the end to ensure we have met the criteria and form an action plan for revision should we need it. When moving through the items, you would make notations on what needs to be improved. Write a brief description of an action plan to improve if you wish. You can refer to the section of the book to read more about the line item for additional help. This book gives practical advice you can apply right away to improve your instructional design capabilities.

By notating how much change is needed to fulfill the criteria and formulating an action plan, designers can take small actionable steps toward designing better learning by using the theories in the book. It is important to note that this checklist cannot possibly consider all criteria for accessibility, but it is a good start and something more achievable than trying to meet all criteria for full accessibility. In fact, what works for one population is often in direct contradiction with what is accessible for another. The way of the future is customizable accessibility features so that users can toggle the settings that make learning best for them. I appreciate the full range of customizability that Apple offers, like a dark mode for when I’m writing in the evening, or the ability to enlarge the text on my phone when reading articles online; many other companies are following suit. If you are in charge of technical procurement, make sure software is accessible and customizable.

Why graphic design needs a rubric

Graphic design is part of the visual communication field, but many mistake it for being part of the arts. It is aesthetic in nature, but it seeks to inform and help communicate messages in a commercial setting. Graphic art is not fine art. Designers do not create for the sake of creation or to express themselves. Instead, they work for their client to design in a way that attracts the audience and helps make the company money. The work is for the client and the client is always right. The livelihood of a designer is not based on how many paintings are sold. Although many fine artists do commission work, many of them just create what they feel like creating and then sell their work. Designers work in the commercial or education space and need to appease stakeholders and clients, Whether there are designing courses alongside subject matter experts and learners or designing websites for a commercial audience, the work is created for others, not for oneself. Because of this difference, fine art is far more subjective. Our idea of what makes great fine art varies. If you could be a fly on the wall in five different homes and look at the art on the wall, you would most likely see five different styles and preferences. Art has some standards to follow in terms of color theory, composition, and balance, but it is far more open to interpretation than graphic design. Graphic design is meant to sell. It is an intentional practice and more of a craft and skill than an art. Its effects are measured in terms of where people look first, second, and third, where people click, how long they stay on a page, and if they struggle with the navigation of a design. There are hundreds of ways we can analyze the effectiveness of graphic design. But, by using a rubric that outlines the major principles and components, we can be sure the outcome of our craft will achieve. Strong graphic design theory aids in instructional design, yet many fail to understand the basic principles or grasp what makes a design range from mediocre to excellent. The principle of contrast is more likely to create a more inclusive design for all . By evaluating one’s own work and the work of others through the use of this checklist, one can begin to understand why the visual aesthetics of design work and aid in instruction.

The importance of rubrics in evaluating e-learning

Using rubrics in e-learning or distance education isn’t new. Rubrics have been around for decades to evaluate the quality of online learning. In Higher Education, organizations such as Quality Matters have popped up to help train designers and instructors on how to evaluate the effectiveness of online education. The Quality Matters rubric and the OSQR (Online SUNY Quality Rubric) have sections that focus on visual design in terms of consistency, but there is very little information or guidance on how to improve the graphic design. For example, the OSQR may alert you to check for inconsistent headers/title fonts. But it may not tell you that your choice in the font is poor, or the color scheme is jarring, or that there is too much clutter on the page. Contemporary rubrics are highly effective at giving a top-level view of everything, but I felt there needed to be a rubric specifically to evaluate how graphic design affects the digital accessibility of our work. The book and the Graphic Design E-Learning Checklist go hand-in-hand, so you can always refer to the section in the checklist by reading the chapter in the book. The QM and OSQR rubrics are not as focused on the two areas I cover in this book. QM and OSQR give a long list of top-level points of evaluation. This book and the checklist in it are not intended to replace the QM or OSQR, but rather to supplement them. My book seeks to use graphic design theory to improve learning by reducing cognitive load.

Cognitive Load Theory

Cognitive load theory is an instructional philosophy based on some aspects of human cognition. The theory focuses on something called secondary knowledge, which is cultural knowledge humans have acquired more recently, rather than over many generations. Secondary knowledge is attained by a processing system in our brains in which the primary aim of instruction is to assist learners in the acquisition of that knowledge. Cognitive load theory as it relates to instructional design revolves around two things: working memory and long-term memory. Short-term memory is limited and used to process new information (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1971).

| Tip: Long-term memory is used to store knowledge that has been acquired for later use. Instruction aims to store information in long-term memory. |

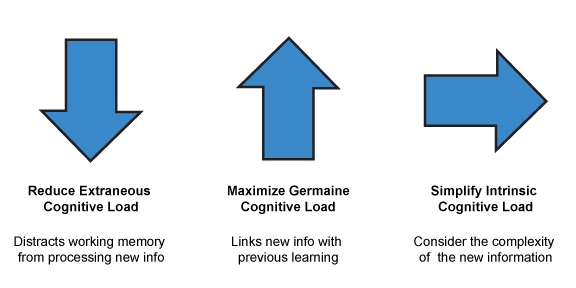

Information acquired during instruction consists of everything that has been learned, including rote memorization of facts all the way up to the synthesis of concepts and procedures. As instructional designers, we want our learners to store the information they are learning in long-term memory so that it can be recalled again later and used as a scaffold on which to add increasingly more challenging material if needed. If learners cannot commit information to long-term memory, they will merely regurgitate information and then forget it. This can be problematic when they try to recall information in the future. We want to optimize intellectual performance by processing information that does not overload the working memory. There are three types of cognitive load. While this book refers mostly to the part called Extraneous Cognitive Load and Intrinsic Cognitive Load, it is important to explain all three. Extraneous cognitive load refers to the way information or tasks are presented to a learner; this is often under the control of an instructional designer. It can distract memory from processing new information. We want to reduce extraneous cognitive load whenever possible.

The second type of cognitive load is called Germane Cognitive Load. Germane Cognitive Load is the deep processing of new information by integrating it with previous learning. This means the work put into creating a permanent store of knowledge. We want to maximize this. Germane load is there when the course is designed and the curriculum materials are delivered to facilitate learning. Some courses have more germane load than others. For example, if you deliver the materials in an engaging and accessible format, you free up the germane load to maximize the resources of the working memory.

Scenario-based learning is a great example of a task that maximizes germane load by helping learners work through solving a problem, versus having them read a giant bulleted list of items to memorize, which is mostly extraneous working memory load. If you were to test a group of students after engaging in scenario-based learning and then test a group of students who are were asked to memorize a long list, you would find the group that did the module about hands-on scenario-based learning scored higher. Cognitive load affects learning and the way we design our courses contributes to the success of our students in the course.

This third type of cognitive load is called Intrinsic Cognitive Load. This deals with the complexity of new information. Instructors may not be able to change the inherent difficulty of the learning, but the work can be broken up into smaller sections. We want to simplify the Intrinsic Cognitive Load. Intrinsic cognitive load should be reduced by simplifying and chunking information and distributing it in a sequence. Smaller chunks are taught first before being explained together as a whole.

By simplifying content into bite-size pieces, we avoid overwhelming the learner. In doing so, we can assure they are more able to grasp new materials when they are presented to them. If we were to present walls and walls of text on a complex subject with no pictures or icons, no space between paragraphs, all content on one page of the course, our learners wouldn’t even be able to look at the page, never mind read it or learn it. We have to break it up, distribute, and explain it in sections. Much like this book. If I didn’t separate the parts and the chapters into sections, the reader would probably lose interest, drift off, and stop reading altogether. We should simplify intrinsic cognitive load, maximize germane cognitive load, and reduce extraneous cognitive load.

In this book, we talk about how to reduce the extraneous working memory load so that we can help facilitate the acquisition of knowledge into long-term memory. As we become more technologically advanced, we need to be aware of how our choices of graphics, animations, fonts, colors, and moving text can create an excess burden on the learner. They have to decode what is happening, which takes up significant brain power that otherwise could have been used to acquire the knowledge in the course and commit it to long-term memory.

Working memory cannot handle that much information. Most people can store and retain only seven items at a time (Miller, 1956). And if the working memory is overloaded, it cannot do its job of acquiring long-term information because the learner can become frustrated, and their decision-making process can become compromised (Baddeley & Hitch, 1974). When a course has confusing navigation or a hard-to-read font, the user has to struggle to find the information they are seeking. Learners can easily become frustrated with the course. This could lead to them doing poorly on their assessment, especially if they cannot find everything, they need to learn to be successful.

When we add visual elements to decorate the page rather than to help inform the material, we create extraneous cognitive load in the form of what Sweller (2011) has termed “seductive details.” Seductive details can also take the form of distracting animations that do not serve a purpose. There are several ways cognitive load can become an issue, but this book tries to address some of the most repeat offenders and offers solutions for improvement. Recent research suggests that designs with a lower perceptual load are less likely to cause the learner to be distracted by any present seductive details. In other words, if your page has only one graphic as a focal point, even if it’s not aiding in instruction, it will not affect learning as much as if you have multiple graphic elements. For this reason, designing with a minimalist approach is best.

Ask yourself what you must include and omit what is unnecessary. If there is an image or element that helps break up the page, or aids in instruction, or explains the activity somehow, you should include it. If not, it’s competing with several other equally distributed or equally sized graphics. Research has shown us that white space is our friend and leaving more of it intact is the goal (Rimmer, n.d.). Since cognitive load theory has to do with the way we process and retain information when we are designing a learning experience, we want our participants to first hold the information in their working memory so that it can be processed sufficiently, and then store it in their long-term memory. To make this happen, we need to reduce barriers and friction by developing material that is easily digested, bite-size, and free from extraneous clutter.

Think about swimming a triathlon, where you know the route by heart and what to expect to get to the finish line. You can focus on the goal and you can push through the challenge with the right amount of desirable difficulty. You know the race will be hard, but you signed up for this, you feel proud of yourself, and you know the reward when you finish will be great. You are enjoying the ride, struggling a little bit as you go, pushing your limits, and feeling proud of yourself.

Swimming in a race is more successful when there are no barriers in the way. Course design should also be free of barriers.Now picture this instead. You are about to start your triathlon. But, as you hop in the water, a bird lands on your head, and you get kicked in the face, and can’t see where you are going, but you flail along anyway. You finally finish your leg, you get out of the water, and you go to look for your bike. You can’t find it and must hunt for it in a large open field where bikes are fallen over haphazardly from the wind, are randomly placed, and scattered on the grass. You finally get to your bike but you feel like giving up. During your run, the signs confuse you as they aren’t clear and you get lost along the way, you trip as you run because there are too many rocks and roots along the trail. By now, you feel defeated. You are in pain, you are disoriented, you don’t know if you even care about the goal of finishing at this point.

I just described two different scenarios. One, where the race had a good degree of desirable difficulty and where there were clear markers on where to go and less friction along the path to the finish line. The second scenario describes a scene in which the path was not clearly marked and was filled with debris and disorder. The second scenario describes what it is like when poor graphic design choices are used in an e-learning experience. The confusing signs are like a poor navbar in a website, or when there are too many places to click. The debris in the road is like having graphic elements that are hard to read. They slow you down. For example, a font set in script with a small point size takes some time to wade through it. The random placement of bikes is like the experience of a learner who is searching for a resource but cannot find it and has to click on multiple places until it’s uncovered. The goal of this book is to show you how we can remove barriers to learning by using visual design theory and digital accessibility best practices. We want all our learners to have access to learning experiences – regardless of how able-bodied they are. Creating good visual design helps us to fulfill the mission of universal design for learning. By creating more access and fewer barriers through technology and design, we can create learning that is beneficial to all.