Chapter 10: Disordered Eating

“Taking care of your body is not the same as obsessively manipulating it.”

-Maria Simpson, bodyloveboss

Though less common than obesity, those who are underweight or who suffer from eating disorders can develop health conditions that can be severe and even life-threatening. Individual eating behaviors can change over time and vary greatly from person to person, but some disordered eating patterns can lead to diagnosable eating disorders. These disorders often coincide with other emotional and psychological issues such as anxiety, depression, perfectionism, and/or low self-esteem. It is important to recognize eating patterns that may be harmful and the signs and symptoms of disordered eating and eating disorders.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the role of body image and other risk factors in the development of disordered eating.

- Identify disordered eating behaviors.

- Differentiate among the characteristics of the most common eating disorders.

- Describe health risks associated with eating disorders and/or being underweight.

- Describe eating disorder treatment including goals.

10.1 Body Image

People that accept, appreciate, and respect their body have a positive body image. Having a positive body image does not mean that you love every aspect of your body. It does, however, describe acceptance for the body with its limitations. Positive body image is associated with higher self-esteem, self-acceptance, and a greater ability to lead a balanced, healthier lifestyle. People with body dissatisfaction have persistent, negative thoughts and feelings about their body and are easily influenced by external factors and pressures to meet a certain “ideal.”1 They often overvalue body image when defining their self-worth, and may experience body dysmorphia, a clinical term describing the inability to stop thinking about a body “flaw” that is either real or imagined. The National Eating Disorders Collaboration of Australia provides a list of signs and symptoms of body dissatisfaction1:

- Repetitive dieting behavior (fasting, counting calories, skipping meals, avoidance of food groups)

- Compulsive or excessive exercise patterns

- Valuing appearance as essential to self-worth (you cannot be successful/loved/valued because you are not attractive/fit/beautiful enough) leading to self-objectification

- Checking behaviors and self-surveillance (measuring body parts, checking reflection often, etc)

- Spending a lot of time on appearance

- Thinking or talking a lot about thinness, muscles, physique and comparing themselves (usually negatively) to others they wish to emulate

- Consistent negative talk (about themselves or others they perceive as heavier)

- Body avoidance (avoiding situations where body image may cause anxiety such as swimming, socializing, etc)

Anyone can be at risk for body dissatisfaction at any age. However, young people are most likely to experience it, especially young women or those with gender dysphoria. Other risk factors for body dissatisfaction include having low self-esteem and/or depression, those who experience teasing or bullying about their appearance, those with role models that express body image concerns or practice unhealthy behaviors, and those with personality traits like perfectionist tendencies, high achievers, rigid “black and white” thinkers. The use of social media plays a role in this as well, especially when viewing and comparing one’s self to unrealistic images and reading appearance-related comments.2 But social media can also be helpful, with online support groups and sites promoting positive body imaging. It is important to recognize the signs of body dissatisfaction. It can lead to unhealthy practices with food, exercise, and/or supplements which do not lead to the desired outcome. This can result in disappointment, shame, and guilt, making these individuals more susceptible to the development of an eating disorder.1

10.2 Disordered Eating

The term disordered eating describes a wide range of eating patterns and can affect anyone at any age. Most of us have undertaken a disordered eating pattern at times such as avoiding a food group, eating what we perceive to be “clean,” or altering food intake and exercise patterns to achieve a specific goal. But when these behaviors become obsessive, more frequent, or begin to interfere with personal or professional activities, the disordered eating has become problematic and may indicate an eating disorder.3 People who exhibit disordered eating may or may not meet the criteria for a diagnosed eating disorder. For example, a person may purge at times, but not often enough to meet the diagnostic criteria for bulimia. However, chronic disordered eating can put people at risk for serious health consequences. Disordered eating behaviors can also progress to a diagnosable eating disorder.4 Signs and symptoms of disordered eating include4:

- Frequent dieting, anxiety associated with specific foods, and/or meal skipping

- Chronic weight fluctuations

- Rigid rituals and routines surrounding food and exercise

- Feelings of guilt and shame associated with eating

- Preoccupation with food, weight, and body image that negatively impacts quality of life

- A feeling of loss of control around food, including compulsive eating habits

- Using exercise, food restriction, fasting, or purging to “make up for bad foods” consumed

10.3 Eating Disorders

Eating disorders are serious but treatable mental conditions that can affect anyone. They are complex medical and psychiatric illnesses considered bio-psycho-social diseases which means that genetic, environmental, biological, and social elements all play a role. Surveys estimate that approximately 20 million women and 10 million men in America will have an eating disorder at some point in their lives. There are many risk factors associated with eating disorders. These include a history of having a close relative with an eating disorder or a mental health condition like anxiety, depression, or addiction. Those experiencing body image dissatisfaction with a history of dieting or who are perfectionists with behavioral inflexibility are more likely to be diagnosed with an eating disorder. Society also plays a role. Just as in several other countries, in the US there is a harmful weight stigma, leading to discrimination or stereotyping of a person based on their weight. Over 60% of those with a diagnosed eating disorder report that they experienced bullying, teasing, and/or weight shaming which contributed to the development of their disorder.3

It is a myth that eating disorders only affect young, white, heterosexual females. In reality, they don’t discriminate, and can affect anyone from all demographics and cultures. Understanding this is critical to ensuring that all can get the help and support they need. Recently more research has focused on eating disorders in varied groups including athletes, those with disabilities, LGBTQIA+ populations, men and boys, people of color, mid-life and older adults.3

For an official diagnosis of an eating disorder one must meet the diagnostic criteria listed by the American Psychological Associations’ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). The most common are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder.

Anorexia Nervosa

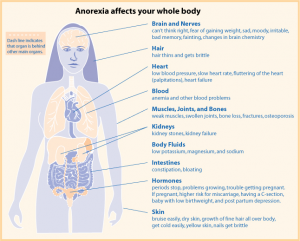

Anorexia nervosa, more often referred to as “anorexia,” is a treatable, life-threatening illness in which a person has an intense fear of weight gain. Their body image is distorted and they believe they are heavier than they actually are. There are two main types of anorexia: restrictive type (severe limitation of food intake), and binge/purge type (cycling between severe limitation of intake, leading to bingeing and purging). Anorexia results in extreme nutrient inadequacy and can eventual lead to organ malfunction. Anorexia is relatively rare—the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) reports that 0.9% of females and 0.3% of males will have anorexia at some point in their lifetime, but it is an extreme example of how an unbalanced diet can affect health. The median age of onset is 18 years old.5 Anorexia frequently manifests during adolescence and those between 15 and 24 with anorexia have 10 times the risk of dying compared to their peers.6

The primary signs and symptoms of anorexia are extremely restricted eating and/or intensive and excessive exercise, extreme thinness (emaciation), relentless pursuit of thinness, unwillingness to maintain a healthy weight, and intense fear of weight gain. The secondary signs and symptoms of anorexia are all related to the caloric and nutrient deficiencies of the unbalanced diet and include excessive weight loss, a multitude of skin abnormalities, diarrhea or extreme constipation, cavities/tooth loss, osteoporosis, low blood pressure, anemia, and infertility. Body temperature also falls due to the loss of fat for insulation. This can lead to lanugo which is the growth of fine hair all over the body. In extreme cases, brain damage and multiple organ failure is possible and anorexia can be fatal. In fact, it has the highest mortality of all mental illnesses with deaths occurring as a result of complications of starvation or suicide. Only about one-third of people with anorexia seek treatment specifically for this disorder.5

Bulimia Nervosa

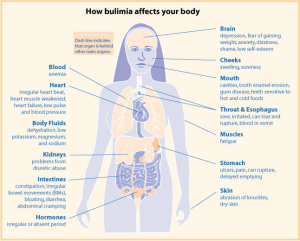

Bulimia nervosa, more often referred to as “bulimia,” like anorexia, is a medical and psychiatric illness that can have severe health consequences. The NIMH reports that 0.5% of females and 0.1% of males will have bulimia at some point in their lifetime. Bulimia is characterized by episodes of eating large amounts of food (bingeing) while feeling a lack of control over eating behavior. This is followed by compensatory behaviors for the overeating including vomiting, the use of laxatives and/or diuretics, fasting, excessive exercise, or a combination of these (purging).

Unlike people with anorexia, those with bulimia often have a healthy or overweight BMI, making the disorder more difficult to detect and diagnose. The disorder is characterized by signs similar to anorexia such as fear of being overweight, extreme dieting, and bouts of excessive exercise. Secondary signs and symptoms include gastric reflux, severe erosion of tooth enamel, dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, lacerations in the mouth, esophageal and peptic ulcers (primarily due to vomiting). Repeated damage to the esophagus puts people with bulimia at an increased risk for esophageal cancer. The disorder is also highly genetic, linked to depression and anxiety disorders, and most commonly occurs in adolescent girls and young women. About 43% of people with bulimia seek treatment which often involves antidepressant or antianxiety medications and nutritional and psychiatric counseling.5

Binge Eating Disorder

Binge eating disorder (BED) is the most common eating disorder in the US. Similar to those who experience anorexia and bulimia, people who have BED have lost control over their eating. They will periodically binge several thousand calories, but their loss of control over eating is not followed by fasting, purging, or compulsive exercise. As a result, people with this disorder are often overweight or obese, and have increased risk of several chronic diseases linked with having an abnormally high body weight such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes. Additionally, they often experience guilt, shame, and depression. BED is commonly associated with depression and anxiety disorders. According to the NIMH, BED is more prevalent than anorexia and bulimia combined, and affects 3.5% of females and 2.0% of males at some point during their lifetime. Treatment often involves antidepressant medication as well as nutritional and psychiatric counseling, and about 43% of people with this disorder seek treatment.5

Other Disordered Eating Patterns

There are several additional patterns of dietary intake that fall under the disordered eating category. Pica involves craving and consuming non-food substances such as dirt, chalk, hair, and others. It is most often observed in children, pregnant women, and individuals with intellectual disabilities.7 Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (AFRID) is also most often seen in children and is more than just “picky” eating. It is defined by a persistent failure to consume adequate calories to meet nutritional and/or energy requirements not associated with body image concerns.4 Orthorexia is the unhealthy obsession with healthy eating until the number and amount of “acceptable” foods consumed does not meet body requirements. It is not an official eating disorder, but may be a form of obsessive-compulsive disorder.3 A category of eating patterns that may not meet specific diagnostic criteria but can be serious and life-threatening fall into a category called Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorders (OSFED; formerly known as Eating Disorders Not Otherwise Specified or EDNOS). These can include atypical anorexia or bulimia, binge eating at low frequency or limited duration, purging disorder, night eating syndrome, or diabulimia which is an eating disorder in type 1 diabetics.3

Table 10.3.1 Eating Disorders: Characteristics and Associated Behaviors4

| Eating Disorder | Characteristics | Behaviors |

| Anorexia Nervosa | Weight loss or lack of appropriate weight gain in children and adolescents; difficulties maintaining appropriate body weight for height, age, stature; distorted body image; intense fear of weight gain | Calorie restriction (self-starvation); some may also experience binge/purge cycles and/or compulsive exercise; preoccupation with weight, food, kcal, dieting; food rituals; avoid meal times or situations involving food; restrained emotions; inflexible thinking; denial of hunger |

| Bulimia Nervosa | Bingeing on excessive kcal, then purging with compensatory behaviors (vomiting, exercise, laxatives, diet pills, diuretics, fasting); weight is typically healthy or overweight and may fluctuate greatly; dry hair, skin, and nails; may also struggle with co-conditions such as self-injury (e.g., cutting), substance abuse, impulsivity | Large amounts of food missing in short time frame; evidence of purging such as frequent trips to bathroom after meals or smelling like vomit; stealing/hoarding food in strange places; excessive use of mouthwash, gum, mints; calluses on back of hand or swelling of cheeks or jaw; frequent dieting; withdrawal from family and friends; weight loss/dieting is a primary concern |

| Binge Eating Disorder (BED) | Recurrent episodes of eating large quantities of food (often very quickly and to the point of discomfort); a feeling of a loss of control during the binge; experiencing shame, distress or guilt afterwards; not regularly using unhealthy compensatory measures (e.g., purging) | Eating alone because of embarrassment about the amount of food consumed; extreme concern with body weight or shape; frequent dieting; withdrawal from family, friends, and activities |

| Orthorexia (Not yet in DSM-5) | Obsession with proper or “healthful” eating (usually treated as a combination of anorexia and obsessive-compulsive disorder) | Compulsive checking of food labels and ingredient lists; only eating foods they consider “healthy” or “clean”; cutting out an increasing number of food groups; unusual interest in the health of what others eat; obsessive following of social media about health and healthy eating |

| Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) | Limitations in type and amount of food consumed, but does not involve stress about body shape/size or fear of fatness; common in those with other disorders like autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, anxiety disorders, intellectual disabilities | Dramatic food restriction; fear of choking; lack of appetite or interest in food; limited range of preferred foods that becomes narrower over time |

| Compulsive Exercise/Muscle Dysmorphia (Not yet in DMS-5) |

Exercise that significantly interferes with important activities, occurs at inappropriate times or in inappropriate settings, or when the individual continues to exercise despite injury or other medical complications; intense anxiety, depression, irritability, feelings of guilt, and/or distress if unable to exercise | Maintaining an excessive, rigid exercise regimen despite weather, fatigue, illness or injury; uncomfortable with rest/inactivity; uses exercise to manage emotions, permission to eat, and/or means of purging kcal; withdrawal from family and friends; feelings of not being fast enough, good enough, or pushing hard enough |

Health Consequences of Being Underweight

The 2015-2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) estimated that 1.5% of adults have BMIs less than 18.5 kg/m2 in the US and are underweight.8 In children, 3% are considered underweight based on BMI for age.9 Being underweight is linked to nutritional deficiencies, especially iron deficiency anemia, and to other problems such as delayed wound healing, hormonal abnormalities, increased susceptibility to infection, and increased risk of some chronic diseases such as osteoporosis. In children, being underweight can stunt growth. The most common underlying cause of underweight in America is inadequate nutrition which can occur with disordered eating patterns or diagnosable eating disorders. Other causes are wasting diseases such as cancer, multiple sclerosis, and tuberculosis. People with wasting diseases are encouraged to seek nutritional counseling with a registered dietitian, as a healthy diet greatly affects survival and improves responses to disease treatments.

10.4 Treating Eating Disorders

Like other illnesses, it is important to seek early treatment for eating disorders. People with eating disorders have a high risk of experiencing additional mental disorders such as anxiety or depression, and are at high risk for substance abuse. The risks of suicide and medical complications are also high. Treatment programs usually involve several health professionals including psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors, registered dietitians, and social workers.3 Treatment can be inpatient or outpatient, and must be tailored to the individual. Usually some sort of individual or group psychotherapy is involved and often includes family members. Some people benefit from medications such as antipsychotics, antidepressants, or mood stabilizers.5

Full recovery is possible, but can take months or years and high levels of commitment from all involved.3 Relapses are the norm rather than the exception. It is difficult to relearn normal eating habits and coping skills and often there are stressors that can initiate a return to disordered behaviors. These stressors include moving (going to college or moving away from home), infertility, pregnancy/birth of a baby, marriage or divorce, financial challenges, menopause, diagnosis of a disease, and/or death of a loved one. There are three areas that must be addressed during treatment: physical recovery, behavioral recovery, and psychological recovery. Goals of treatment include3:

- Addressing any immediate medical concerns caused by the disorder

- Reducing or eliminating disordered behaviors

- Addressing issues like depression, anxiety or trauma

- Developing a plan to prevent relapse

Key Takeaways

- Body dissatisfaction is associated with risk of developing disordered eating or an eating disorder.

- Disordered eating describes a wide range of eating patterns that are common and can affect anyone at any age. Disordered eating that becomes frequent and obsessive can lead to negative health consequences including the development of diagnosable eating disorders.

- Eating disorders are complex medical and psychiatric illnesses that can affect anyone. To be diagnosed one must meet the criteria in the American Psychological Association Diagnostic Manual (DMS-5).

- The most commonly diagnosed eating disorder is binge eating disorder followed by bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa.

- People with eating disorders have lost control over their eating patterns, causing many negative health consequences. The entire body is affected by the disorder.

- Treatment of eating disorders includes a multidisciplinary team of professionals, family and friends, and individual commitment to treatment. Relapse is common, but full recovery is possible.

- National Eating Disorders Collaboration. (2021, March). Body image fact sheet. https://nedc.com/au/assets/Fact-Sheets/NEDC-Fact-Sheet-Body-Image.pdf

- Holland, G., Tiggemann, M. (2016, June). A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image, 17, 100-110. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.02.008

- National Eating Disorders Association. (n.d.). What are eating disorders? https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/what-are-eating-disorders

- Anderson, M. (2018). What is disordered eating? Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. https://www.eatright.org/health/diseases-and-conditions/eating-disorders/what-is-disordered-eating)

- The National Institute of Mental Health. (2016). Eating disorders. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders/index.shtml

- Smink, F. E., van Hoeken, D., & Hoek, H. W. (2012). Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Current Psychiatry Reports, 14(4), 406-414. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y

- Advani, S., Kochhar, G., Chachra, S., & Dhawan, P. (2014). Eating everything except food (PICA): A rare case report and review. Journal of International Society of Preventive & Community Dentistry, 4(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.4103/2231-0762.127851

- Fryer, C. D., Carroll, M. D, & Ogden, C. L. (2018, September). Prevalence of underweight among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 1960-62 through 2015-16. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/underweight_adult_15_16/underweight_adult_15_16.htm

- Fryer, C. D., Carroll, M. D., & Ogden, C. L. (2018, September). Prevalence of underweight among children and adolescents aged 2-19 and over: United States, 1963-65 through 2015-16. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/underweight_child_15_16/underweight_child_15_16.htm

A disturbed and unhealthy eating pattern that may or may not meet the diagnostic criteria for an eating disorder.