Chapter 18: Nutrition Through the Lifecycle

“A healthy outside starts from the inside.”

–Robert Urich (1946-2002), American actor

Human bodies change significantly over time, and food is the fuel for those changes. People of all ages need the same basic nutrients—amino acids, carbohydrates, fatty acids, vitamins and minerals, water—to sustain life and health. However, the amounts of nutrients needed differ. Throughout the human life cycle, the body constantly changes and goes through different periods known as stages. In this chapter we will discuss the major changes that occur during each stage, focusing on the roles nutrition plays. The major stages of the human life cycle are defined as follows:

- Pregnancy. The development of a zygote into an embryo and then into a fetus in preparation for childbirth.

- Infancy. The earliest part of childhood. It is the period from birth through age 1.

- Toddler years. Occur during ages 2 and 3 and are the end of early childhood.

- Childhood. Takes place from ages 4 to 8.

- Puberty. The period from ages 9 to 13, which is the beginning of adolescence.

- Older adolescence. The stage that takes place between ages 14 and 18.

- Adulthood. The period from adolescence to the end of life. Begins at age 19.

- Middle age. The period of adulthood that stretches from age 31 to 50.

- Senior years, or old age. Extends from age 51 until the end of life.

Learning Objectives

- Summarize prenatal nutritional requirements and dietary recommendations.

- Discuss the most important nutritional concerns during pregnancy.

- Discuss the benefits and barriers related to breastfeeding.

- Examine feeding problems that parents and caregivers may face with their infants.

- Explore the introduction of solid foods into a toddler’s diet.

- Discuss the most important nutrition-related concerns during childhood.

- Discuss the most important nutrition-related concerns during adolescence.

- Explain how nutritional and lifestyle choices can affect current and future health.

- Discuss the most important nutrition-related concerns during middle and old age.

18.1 Pregnancy

Conception to the Early Days of Pregnancy

Women who are trying to conceive should make proper dietary choices and practice healthy habits to ensure the delivery of a healthy baby. Fathers-to-be should also consider their lifestyles. For both men and women, a sedentary lifestyle, excess body weight, and a diet low in fresh fruits and vegetables may affect fertility. Men who consume too much alcohol, use certain drugs, and/or smoke cigarettes/use tobacco may also damage the quantity and quality of their sperm.1 For both men and women, adopting healthy habits also boosts general well-being and makes it possible to meet the demands of parenting.

Pregnancy is measured from the first day of a woman’s last menstrual period until childbirth, and typically lasts about 40 weeks. Humans like to think of pregnancy in terms of equal time, so we divide pregnancy into three approximately equal sections or trimesters. The first trimester is the first 13 weeks of pregnancy, the second is weeks 14 through 27, and pregnancy ends with the third trimester, weeks 28 through birth.

However, trimesters do not reflect the actual stages of development through the pregnancy. The first trimester encompasses several stages of development. At conception, a sperm cell fertilizes an egg cell, creating a zygote. This first stage of pregnancy accounts for the first 2 weeks. The zygote rapidly divides into multiple cells to become an embryo and implants itself in the uterine wall. Major changes begin to occur in these earliest days after conception, often weeks before a woman even knows that she is pregnant. The embryonic stage lasts from week 3 through week 10. During this time there are critical periods of development where the infrastructure for organ systems such as the nervous system, heart, limbs, ears, eyes, teeth, palate, and external genitalia is laid down. During these periods the developing embryo is very sensitive to damage caused by inadequate nutrition, medications, alcohol, or exposure to other harmful substances. Adequate nutrition supports cell division, tissue differentiation, and organ development, especially during these critical times. As each week passes, new milestones are reached. The end of the embryonic stage marks the start of the fetal stage which is week 11 through birth. During this stage the organ systems grow to maturity, and weight of the fetus increases from about 1 oz to about 7.5 lb. At the 20-week mark, physicians typically perform an ultrasound to acquire information about the fetus and check for abnormalities. By this time, it is possible to know the sex of the baby.

Good nutrition is vital for any pregnancy and not only helps an expectant mother remain healthy, but also impacts the development of the fetus and ensures that the baby thrives in infancy and beyond. During pregnancy, a woman’s needs increase for certain nutrients more than for others. If these nutritional needs are not met, infants could suffer from low birth weight (a birth weight less than 5.5 lb, or 2,500 grams), among other developmental problems. Therefore, it is crucial to make careful dietary choices.

Weight Gain during Pregnancy

During pregnancy, a mother’s body changes in many ways. One of the most notable and significant changes is weight gain. If a pregnant woman does not gain enough weight, her unborn baby will be at risk. Infant birth weight is one of the best indicators of a baby’s future health. Poor weight gain by the mother, especially in the third trimester, could result not only in low birth weight, but also in infant intellectual disabilities or mortality. Therefore, it is vital for a pregnant woman to maintain a healthy weight, and her weight prior to pregnancy also has a major effect. Pregnant women at a healthy weight pre-pregnancy should gain between 25-35 lb in total through the entire pregnancy. The precise amount that a mother should gain usually depends on her beginning body mass index (BMI).

Table 18.1.1 Recommended Weight Gain During Pregnancy

| Pre-Pregnancy BMI | Weight Category | Recommended Weight Gain |

| < 18.5 | Underweight | 28-40 lb |

| 18.5-24.9 | Healthy | 25-35 lb |

| 25.0-29.9 | Overweight | 15-25 lb |

| > 30.0 | Obese (all classes) | 11-20 lb |

Starting weight below or above the healthy range can lead to different complications. Pregnant women with a pre-pregnancy BMI below 20 kg/m2 are at a higher risk of a preterm delivery and an underweight infant. Pregnant women with a pre-pregnancy BMI above 30 kg/m2 have an increased risk of the need for a cesarean section during delivery. Therefore, it is optimal to have a BMI in the normal range prior to pregnancy.

Generally, women gain 2 to 5 lb in the first trimester. After that, it is recommended to gain no more than one lb per week until birth. Some of the new weight is due to the growth of the fetus, while some is due to changes in the mother’s body that support the pregnancy. Weight gain often breaks down in the following manner: 6 to 8 lb of fetus, 1 to 2 lb for the placenta (which supplies nutrients to the fetus and removes waste products), 2 to 3 lb for the amniotic sac (which contains fluids that surround and cushion the fetus), 1 to 2 lb in the breasts, 1 to 2 lb in the uterus, 3 to 4 lb of maternal blood, 3 to 4 lb maternal fluids, and 8 to 10 lb of extra maternal fat stores that will be needed for breastfeeding and delivery for a total of 25-35 lb. Women who are pregnant with more than one fetus are advised to gain even more weight to ensure the health of their unborn babies.

Weight Loss after Pregnancy

During labor, new mothers lose some of their gained weight (usually 9-13 lb) with the delivery of their child (weight of the baby, the placenta, and the amniotic fluid). In the following weeks, they continue to shed weight as they lose accumulated fluids and their blood volume returns to normal. Some studies have found that exclusive breastfeeding helps a new mother lose some of the extra weight when compared to non-exclusive breastfeeding.2

New mothers who gain the recommended amount of weight and participate in regular physical activity during their pregnancies have an easier time shedding weight post-pregnancy. However, women who gain more weight than needed for a pregnancy typically retain that excess weight as body fat. If that weight gain increases a new mother’s BMI by a unit or more, that could lead to complications such as hypertension or gestational diabetes in future pregnancies and later in life.

Nutritional Requirements

As a mother’s body changes, so do her nutritional needs. Pregnant women must consume more kcal and nutrients in the second and third trimesters than other adult women. However, the average recommended daily caloric intake can vary depending on activity level and the mother’s normal weight. Regardless, pregnant women should choose a high quality, diverse diet, consume fresh foods, and nutrient-rich meals. It is also standard for pregnant women to take prenatal supplements to ensure adequate intake of necessary micronutrients.

Energy and Macronutrients

During the first trimester, a pregnant woman has the same energy requirements as normal and should consume the same number of kcal as usual. However, as the pregnancy progresses, a woman must increase her caloric intake. A pregnant woman should consume an additional 340 kcal per day during the second trimester, and an additional 450 kcal per day during the third trimester.3 This is partly due to an increase in metabolism which rises during pregnancy. A woman can easily meet these increased needs by consuming more nutrient dense foods.

The recommended dietary allowance, or RDA, of carbohydrates during pregnancy is about 175 to 265 g per day to fuel fetal brain development. The best food sources for pregnant women include whole grain breads and cereals, brown rice, whole vegetables, legumes, and fruits. These and other unrefined carbohydrates provide nutrients, phytochemicals, antioxidants, and the extra 3 mg/day of fiber that is recommended during pregnancy. These foods also help to build the placenta and supply energy for the growth of the unborn baby.

During pregnancy, extra protein is needed for the synthesis of new maternal and fetal tissues. Protein builds muscle and other tissues, enzymes, antibodies, and hormones in both the mother and the unborn baby. Additional protein also supports increased blood volume and the production of amniotic fluid. Protein should be derived from healthy sources, such as lean red meat, poultry, legumes, nuts, seeds, eggs, and fish. Low-fat milk and other dairy products also provide protein, along with calcium and other micronutrients. To calculate protein needs during pregnancy, use pre-pregnancy weight in kg body weight times the RDA for protein (0.8 g/kg/day), and add 25 g. For example, if your pre-pregnancy weight was 150 lb:

- Convert 150 lb to kg by dividing by 2.2: 150 lb ÷ 2.2 lb/kg = 68 kg

- Multiply 68 kg by RDA: 68 kg x 0.8 g/kg/day = 54.5 g protein

- Add 25 g during second and third trimester: 54.5 g + 25 g = ~80 g protein

There are no specific recommendations for fats in pregnancy, apart from following normal dietary guidelines. However it is recommended to increase the amount of essential fatty acids (omega-3 and omega-6) because they are incorporated into the placenta and fetal tissues. Fats should make up 25-35% of daily kcal and should come from healthy sources, such as avocados, nuts and nut butters, and olives and olive oils. It is not recommended for pregnant women to be on a very low-fat diet, since it would be hard to meet the needs of essential fatty acids and fat soluble vitamins. Fatty acids are important during pregnancy because they support the baby’s brain and eye development.

Fluids

Fluid intake must also be monitored. According to the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), pregnant women should drink at least 2.3 liters (about 10 cups) of liquids per day to provide enough fluid for blood production.4 It is also important to drink additional liquids during physical activity or when it is hot and humid outside, to replace fluids lost via perspiration. The combination of a high fiber diet and lots of liquids also helps to eliminate waste.

Vitamins and Minerals

The daily requirements for women change with the onset of a pregnancy. Taking a daily prenatal supplement or multivitamin helps to meet many nutritional needs. However, most of these requirements should be fulfilled with a healthy diet. The following table compares the non-pregnant levels of required vitamins and minerals to the levels needed during pregnancy. For pregnant women, the RDA of nearly all vitamins and minerals increases.

Table 18.1.2 Recommended Micronutrient Intakes during Pregnancy

| Nutrient | Non-Pregnant Women | Pregnant Women |

| Vitamin A (mcg) | 700.0 | 770.0 |

| Thiamin (mg) | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| Riboflavin (mg) | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| Niacin (mg) | 14.0 | 18.0 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 1.3 | 1.9 |

| Folate (mcg) | 400.0 | 600.0 |

| Vitamin B12 (mcg) | 2.4 | 2.6 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 75.0 | 85.0 |

| Vitamin D (mcg) | 15.0 | 15.0 |

| Vitamin E (mg) | 15.0 | 15.0 |

| Calcium (mg) | 1000.0 | 1000.0 |

| Iron (mg) | 18.0 | 27.0 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 310.0 (19-30 yr) | 350.0 (19-30 yr) |

| 320.0 (31-50 yr) | 360.0 (31-50 yr) | |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 700.0 | 700.0 |

| Zinc (mg) | 8.0 | 11.0 |

The micronutrients involved with building the skeleton—vitamin D and calcium—are crucial during pregnancy to support fetal bone development. Although the recommended levels are the same as those for non-pregnant women, many women do not typically consume adequate amounts and should make an extra effort to meet those needs.

There is an increased need for all B vitamins during pregnancy. Adequate vitamin B6 supports the metabolism of amino acids, while more vitamin B12 is needed for the synthesis of red blood cells and DNA. Additional zinc is crucial for cell development and protein synthesis. The need for vitamin A also increases, and extra iron intake is important because of the increase in blood supply during pregnancy and to support the fetus and placenta. Iron needs increase by 1/3, and this increase is almost impossible to obtain in adequate amounts from food sources during pregnancy. Therefore, even if a pregnant woman consumes a healthy diet, there may still be a need to take an iron supplement, in the form of ferrous salts. Also remember that folate needs increase during pregnancy to 600 mcg per day to prevent neural tube defects (during the first 8 weeks of pregnancy). This micronutrient is also crucial because it helps produce the extra blood a woman’s body requires during pregnancy.

For other micronutrients, recommended intakes are the same as those for non-pregnant women, although it is crucial for pregnant women to make sure to meet the RDAs to reduce the risk of birth defects. In addition, pregnant mothers should avoid exceeding any recommendations. Taking megadose supplements can lead to excessive amounts of certain micronutrients, such as vitamin A and zinc, which may produce toxic effects that can also result in birth defects.

Guide to Eating during Pregnancy

Almost all of the modified energy and nutrient needs required during pregnancy can be met by consuming nutrient dense foods, which are essential to a healthy diet. Examples of nutrient dense foods include fruits, vegetables, whole grains, peas, beans, reduced-fat dairy, and lean meats. Pregnant women should be able to meet almost all of their increased needs via a healthy diet. However, as discussed previously, expectant mothers should take a prenatal supplement to ensure an adequate intake of iron and folate. Here are some additional dietary guidelines for pregnant women4:

- Eat iron-rich or iron-fortified foods, including meat or meat alternatives, breads, and cereals, to help satisfy increased need for iron and prevent anemia. Include vitamin C-rich foods, such as orange juice, broccoli, or strawberries, or peppers to enhance iron absorption.

- Eat a well-balanced diet including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, calcium-rich foods, lean meats, and a variety of cooked seafood (excluding fish that are high in mercury, such as swordfish and shark).

- Drink additional fluids, especially water.

Foods to Avoid

A number of substances can harm a growing fetus. Therefore, it is vital for women to avoid them throughout a pregnancy. Some are so detrimental that a woman should avoid them even if she suspects that she might be pregnant. For example, consumption of alcoholic beverages results in a range of abnormalities that fall under the umbrella of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. They include learning and attention deficits, heart defects, and abnormal facial features. Alcohol enters the unborn baby via the umbilical cord and can slow fetal growth, damage the brain, or even result in miscarriage. The effects of alcohol are most severe in the first trimester, when the organs are developing. As a result, there is no safe amount of alcohol that a pregnant woman should consume.

Pregnant women should also limit caffeine intake, which is found not only in coffee, but also tea, colas, cocoa, chocolate, and some over-the-counter painkillers. Some studies suggest that very high amounts of caffeine have been linked to babies born with low birth weights. Most experts agree that small amounts of caffeine each day are safe for most pregnant women (approximately 200 mg/day or less)5 but check with your doctor.

For both mother and child, foodborne illness can cause major health problems. For example, the foodborne illness caused by the bacteria Listeria monocytogenes can cause spontaneous abortion and fetal or newborn meningitis. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), pregnant women are 10 times more likely to become infected with this disease than non-pregnant, healthy adults.6 Foods more likely to contain the bacteria and that should be avoided include unpasteurized dairy products, especially soft cheeses, smoked seafood, hot dogs, paté, cold cuts, and uncooked meats.

Pregnant women can eat fish, ideally 8 to 12 oz of different types each week. Expectant mothers are able to eat cooked shellfish such as shrimp, farm-raised fish such as salmon, and a maximum of 6 oz of albacore or white, tuna per week. However, they should avoid fish with high methylmercury levels, such as shark, swordfish, and king mackerel. (Please refer to Table 3.3.2 Mercury Levels in Fish in Chapter 3). Pregnant women should also avoid consuming raw fish to avoid foodborne illness.

Food Cravings and Aversions

Food aversions and cravings can occur during pregnancy and often get a lot of attention. Fortunately most do not have a major impact unless food choices are extremely limited. For most women, it is not harmful to indulge in the occasional craving, such as a desire for pickles and ice cream. However, a medical disorder known as pica, the craving and willing consumption of substances with little or no nutritive value, such as dirt, clay, or laundry starch, can be harmful. Pica is most prevalent among pregnant women and young children. Although the etiology (or cause) of pica is not completely understood, several studies have linked pica, particularly during pregnancy, to iron deficiency anemia.7

Physical Activity during Pregnancy

For most pregnant women, physical activity is a must and is recommended in the 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Regular exercise of moderate intensity, about 30 minutes per day most days of the week, keeps the heart and lungs healthy. It also helps to improve sleep and boosts mood and energy levels. In addition, women who exercise during pregnancy report fewer discomforts and may have an easier time losing excess weight after childbirth. Brisk walking, swimming, or an aerobics class geared toward expectant mothers are all great ways to get exercise during a pregnancy. Healthy women who already participate in vigorous activities, such as running, can continue doing so during pregnancy provided they discuss their exercise plan with their physicians.

However, pregnant women should avoid activities that could cause injury, such as soccer, football, and other contact sports, or activities that could lead to falls, such as horseback riding and downhill skiing. It may be best for pregnant women not to participate in certain sports, such as tennis, that require you to jump or change direction quickly. Scuba diving should also be avoided because it might result in the fetus developing decompression sickness.

Complications during Pregnancy

Expectant mothers may face different complications during the course of their pregnancy. They include certain medical conditions that could greatly impact a pregnancy if left untreated, such as gestational hypertension and gestational diabetes, which have diet and nutrition implications.

Gestational Hypertension

Gestational hypertension is a condition of high blood pressure during the second half of pregnancy. First time mothers are at a greater risk, along with women who have mothers or sisters who had gestational hypertension, women carrying multiple fetuses, women with a prior history of high blood pressure or kidney disease, and women who are overweight or obese when they become pregnant. Hypertension can prevent the placenta from getting enough blood, which would result in the baby getting less oxygen and nutrients. This can result in low birth weight, although most women with gestational hypertension can still deliver a healthy baby if the condition is detected and treated early.

Some risk factors for gestational hypertension can be controlled such as diet, while others cannot, such as family history. If left untreated, gestational hypertension can lead to a serious complication called preeclampsia, which is sometimes referred to as toxemia. This disorder is marked by elevated blood pressure, protein in the urine, and is associated with fluid retention and swelling. If preeclampsia worsens, a life-threatening condition for both the mother and the baby called eclampsia can occur.

Gestational Diabetes

About 8% of pregnant women suffer from a condition known as gestational diabetes, or abnormal glucose tolerance during pregnancy.8 As discussed in Chapter 5, gestational diabetes is similar to type 2 diabetes. The mother’s body becomes resistant to the hormone insulin, which enables cells to transport glucose from the blood and into cells. Gestational diabetes is typically diagnosed between 24-28 weeks using a glucose tolerance test, although it is possible for the condition to develop later into a pregnancy. Signs and symptoms include extreme hunger, thirst, or fatigue. The excess glucose in the mother’s blood is transported to the placenta, and the fetus will take up this excess glucose from the mother. If blood glucose levels are not properly monitored and treated, the baby might gain too much weight, possibly causing a premature birth and/or a difficult delivery. Diet and regular physical activity can help to manage this condition. Some patients with gestational diabetes may require daily insulin injections to boost the absorption of glucose from the bloodstream and promote the storage of glucose in the form of glycogen in liver and muscle cells. Gestational diabetes usually resolves quickly after childbirth, however women who suffer from this condition have a 50% chance of eventually developing type 2 diabetes later in life, particularly if they are overweight.

18.2 Breastfeeding

After the birth of the baby, nutritional needs must be met to ensure that an infant not only survives, but thrives from infancy into childhood. Exclusive breastfeeding is one of the best ways a mother can support the growth and protect the health of her infant child.

Breast milk contains all of the nutrients that a newborn requires for rapid growth and development and gives a child the best start to a healthy life. New mothers must consider their own nutritional requirements to help their bodies recover in the wake of the pregnancy and delivery. This is particularly true for women who breastfeed their babies, which calls for an increased intake of certain nutrients.

Benefits of Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding has a number of benefits, both for the mother and for the child. Breast milk contains immunoglobulins, enzymes, immune factors, and white blood cells. As a result, breastfeeding boosts the baby’s immune system and lowers the incidence of diarrhea, along with respiratory diseases, gastrointestinal problems, and ear infections. Breastfed babies also are less likely to develop asthma and allergies, and breastfeeding lowers the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). In addition, human milk encourages the growth of healthy bacteria in an infant’s intestinal tract. All of these benefits remain in place long after an infant has been weaned from breast milk. Some studies suggest other possible long-term effects. For example, breast milk may protect against type 1 diabetes and obesity, although research is ongoing in these areas.9

Breastfeeding has a number of benefits, both for the mother and for the child. Breast milk contains immunoglobulins, enzymes, immune factors, and white blood cells. As a result, breastfeeding boosts the baby’s immune system and lowers the incidence of diarrhea, along with respiratory diseases, gastrointestinal problems, and ear infections. Breastfed babies also are less likely to develop asthma and allergies, and breastfeeding lowers the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). In addition, human milk encourages the growth of healthy bacteria in an infant’s intestinal tract. All of these benefits remain in place long after an infant has been weaned from breast milk. Some studies suggest other possible long-term effects. For example, breast milk may protect against type 1 diabetes and obesity, although research is ongoing in these areas.9

Breastfeeding has a number of other important benefits. It is easier for babies to digest breast milk than bottle formula, which often contains proteins made from cow’s milk that require an adjustment period for infant digestive systems. Breastfed infants are sick less often than formula-fed infants. Breastfeeding is more sustainable and results in less plastic waste and other trash. Breastfeeding can also save families money because it does not incur the same cost as purchasing formula. Breast milk is always ready. It does not have to be mixed, heated, or prepared. Also, breast milk is sterile and always at the right temperature. In addition, the skin-to-skin contact of breastfeeding promotes a close bond between mother and baby, which provides important emotional and psychological benefits. The practice also provides health benefits for the mother. Studies have shown that breastfeeding reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes, and breast and ovarian cancers for the mother.9

The choice to breastfeed is one that all new mothers face. Although breast milk is ideal for almost all infants, there are some challenges that nursing mothers may face when starting and continuing to breastfeed their infants. These obstacles include painful engorgement or fullness in the breasts, sore and tender nipples, lack of comfort or confidence in public, and lack of accommodation to breastfeed or express milk in the workplace. Support from family members, friends, employers, and others can greatly help with both the decision making process during pregnancy and the practice of breastfeeding after the baby’s birth. In the US in 2015, about 83% of babies started out being breastfed. Yet by the age of six months, when solid foods should begin to be introduced, only 24% of infants were still breastfed exclusively. Employed mothers have been less likely to initiate breastfeeding and tend to breastfeed for a shorter period of time than new mothers who are not employed outside the home or who have lengthy maternity leaves.10 Around the world, less than 40% of infants under the age of six months are breastfed exclusively.11

International Board Certified Lactation Consultants are healthcare professionals (often a registered nurse or registered dietitian) certified in breastfeeding management that work with new mothers to solve problems and educate families about the benefits of this practice. Women who give birth in hospitals with lactation consultants are more likely to breastfeed. Once a new mother has left the hospital for home, she also needs access to a trained individual who can provide consistent information.12 Lactation consultants can help new mothers learn proper technique, and help troubleshoot breastfeeding problems when they occur.

Affordable Care Act and Breastfeeding

In 2010 in the US, the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) called for employers to provide accommodations within the workplace for new mothers to pump breast milk. This law requires a private and clean space within the workplace, other than a restroom, along with adequate break time for a woman to express milk. Yet as of 2018 only 49% of employers provided worksite lactation support programs.10

Contraindications to Breastfeeding

Although there are numerous benefits to breastfeeding, in some cases there are also risks that must be considered. A new mother with HIV should not breastfeed as the infection can be transmitted through breast milk. Breastfeeding is also not recommended for women undergoing radiation or chemotherapy treatment for cancer. Women actively using alcohol excessively and/or illicit drugs should also avoid breastfeeding.

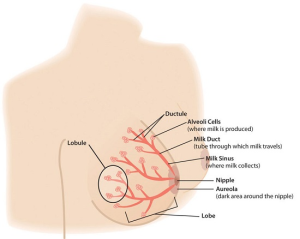

Lactation

Lactation (or lactogenesis) is the synthesis and secretion of breast milk. An infant suckling at the breast stimulates nerve endings which signal the pituitary gland to release two hormones, prolactin and oxytocin. Prolactin signals the growth of the milk duct system and initiates and maintains milk production in the alveoli of the breast.

Oxytocin is involved in milk ejection, also called milk letdown. It signals contraction of the alveoli cells, forcing milk into the ducts and out through the nipple. The nipple tissue becomes firmer with stimulation, which makes it more flexible and easier for the baby to grasp in the mouth. The release of oxytocin also has psychological benefits by inducing calm and enhancing feelings of affection or bonding between mother and baby.13

New mothers need to adjust their caloric and fluid intake to make breastfeeding possible. The RDA is 330 additional kcal per day during the first six months of lactation and 400 additional kcal during the second six months of lactation. The energy needed to support breastfeeding comes from both increased intake and from stored fat. For example, during the first six months after her baby is born, the daily caloric cost for a lactating mother is 500 kcal, with 330 kcal derived from increased intake and 170 kcal derived from maternal fat stores. This helps explain why breastfeeding may promote weight loss in new mothers. Lactating women should also drink approximately 13 cups of liquids per day to maintain milk production, according to the NAM. As is the case during pregnancy, the RDA of several vitamins and minerals increases for women who are breastfeeding their babies. The following table compares the recommended vitamins and minerals for lactating women to the levels for non-pregnant and pregnant women.

Table 18.2.1 Recommended Micronutrient Intakes during Pregnancy

| Nutrient | Non-Pregnant Women | Pregnant Women | Lactating Women |

| Vitamin A (mcg) | 700.0 | 770.0 | 1300.0 |

| Thiamin (mg) | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Riboflavin (mg) | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| Niacin (mg) | 14.0 | 18.0 | 17.0 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 1.3 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| Folate (mcg) | 400.0 | 600.0 | 500.0 |

| Vitamin B12 (mcg) | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.8 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 75.0 | 85.0 | 120.0 |

| Vitamin D (mcg) | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 |

| Vitamin E (mg) | 15.0 | 15.0 | 19.0 |

| Calcium (mg) | 1000.0 | 1000.0 | 1000.0 |

| Iron (mg) | 18.0 | 27.0 | 9.0 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 310.0 (19-30 yr) | 350.0 (19-30 yr) | 310.0 (19-30 yr) |

| 320.0 (31-50 yr) | 360.0 (31-50 yr) | 320.0 (31-50 yr) | |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 700.0 | 700.0 | 700.0 |

| Zinc (mg) | 8.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 |

Calcium requirements do not change during breastfeeding because of more efficient absorption, which is the case during pregnancy, as well. However, the reasons for this differ. During pregnancy, there is enhanced absorption of calcium within the gastrointestinal tract. During lactation, there is enhanced retention by the kidneys. The RDA for phosphorus, vitamin D, and fluoride also remain the same. The RDA for iron is reduced significantly during lactation to half of the requirement for non-pregnant women. This is because, for most women, lactation significantly reduces or eliminates menstruation.

Components of Breast Milk

Human breast milk not only provides adequate and highly bioavailable nutrition for infants, it also helps to protect newborns from disease. Breast milk is rich in cholesterol, which is needed for brain development. Colostrum is produced immediately after birth, prior to the start of milk production, and lasts for several days after the arrival of the baby. Colostrum is thicker than breast milk, and is often yellowish in color. This protein-rich liquid fulfills an infant’s nutrient needs during those early days. Although low in volume, colostrum is packed with concentrated nutrition for newborns. This special “milk” is high in fat-soluble vitamins, minerals, and immunoglobulins (antibodies) that pass from the mother to the baby. Immunoglobulins provide passive immunity for the newborn and protect the baby from bacterial and viral diseases.14

Two to four days after birth, colostrum is replaced by transitional milk. Transitional milk is a creamy liquid that lasts for approximately two weeks and includes high levels of fat, lactose, and water soluble vitamins. It also contains more kcal than colostrum.

Mature milk is the final fluid that a new mother produces. In most women, this begins by the end of the second week postpartum. There are two types of mature milk that appear during a feeding. Foremilk occurs at the beginning and includes more water, vitamins, and protein. Hindmilk occurs after the initial release of milk and contains higher levels of fat, which is necessary for weight gain. Combined, these two types of milk ensure that a baby receives adequate nutrients to grow and develop properly.15

About 90% of mature milk is water, which helps an infant remain hydrated. The remaining 10% contains carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, which support energy and growth. Similar to cow’s milk, the main carbohydrate of mature breast milk is lactose. Breast milk contains vital essential fatty acids, such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and arachidonic acid (ARA). In terms of protein, breast milk contains more whey than casein (which is the reverse of cow’s milk). Whey is much easier for infants to digest than casein. Complete protein, which means all of the essential amino acids, is also present in breast milk, as well as lactoferrin, an iron-gathering compound that helps to absorb iron into an infant’s bloodstream.

In addition, breast milk provides adequate vitamins and minerals. Although absolute amounts of some micronutrients are low, they are more efficiently absorbed by infants. Other essential components include digestive enzymes that help a baby digest the breast milk. Human milk also provides the hormones and growth factors that help a newborn to develop.

Diet and Milk Quality

A mother’s diet can have a major impact on milk production and quality. As during pregnancy, lactating mothers should avoid harmful substances such as tobacco. Some legal drugs and herbal products can be harmful as well, so it is important to discuss them with a healthcare provider. Some mothers may need to avoid certain things, such as spicy foods, that can produce gas in sensitive infants. Avoiding alcohol completely is the safest option for a breastfeeding mother. However, consumption of up to one alcoholic drink a day (12 oz of beer, 5 oz of wine, or 1.5 oz of liquor) is not known to be harmful to the infant, particularly if the mother waits 2-3 hours after consumption to breastfeed.16

In terms of the mother’s nutrient intake, there is limited research regarding the extent of its role on breast milk composition. A systematic review of 36 journal publications found that the concentration of fatty acids and vitamins A, C, B6, and B12 are reported to be most influenced by maternal diet, while mineral content is much less affected.17 However, more research on this topic is needed.

Bottle Formula Feeding

Most women can and should breastfeed when given sufficient education and support. However, as discussed, a small percentage of women are unable to breastfeed their infants, while others choose not to. While infant formula provides a balance of nutrients, not all formulas are the same and there are important considerations that parents and caregivers must weigh. Standard formulas use cow’s milk as a base. They have 20 kcal per fl oz, similar to breast milk, with vitamins and minerals added. Cow’s milk alone should never be given to babies under the age of one as young infants cannot fully digest it and it does not meet their nutrient needs. Soy-based formulas are usually given to infants who develop diarrhea, constipation, vomiting, colic, or abdominal pain, or to infants with a cow’s milk protein allergy.

Hypoallergenic protein hydrolysate formulas are usually given to infants who are allergic to cow’s milk and soy protein. This type of formula uses hydrolyzed protein, meaning that the protein is already broken down into amino acids and small peptides, which makes it easier to digest. Preterm infant formulas are given to low birth weight infants, if breast milk is unavailable. Preterm infant formulas have 24 kcal per fl oz and are given until the infant reaches a desired weight.

Infant formula comes in three basic types:

- Powder that requires mixing with water. This is the least expensive type of formula.

- Concentrates, which are liquids that must be diluted with water. This type is slightly more expensive.

- Ready-to-use liquids that can be poured directly into bottles. This is the most expensive type of formula. However, it requires the least amount of preparation. Ready-to-use formulas are also convenient for traveling.

Most babies need about 2.5 oz of formula per lb of body weight each day. Therefore, the average infant should consume about 24 fl oz of breast milk or formula per day. When preparing formula, parents and caregivers should carefully follow the safety guidelines, since an infant has an immature immune system. All equipment used in formula preparation should be sterilized. Prepared, unused formula should be refrigerated to prevent bacterial growth. Parents should make sure not to use contaminated water to mix formula in order to prevent foodborne illnesses. Follow the instructions for powdered and concentrated formula carefully. Formula that is overly diluted would not provide adequate kcal and protein, while overly concentrated formula provides too much protein and too little water which can impair kidney function.

It is important to note again that both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the World Health Organization (WHO) state that breast milk is far superior to infant formula. This table compares some of the advantages of giving a child breast milk to the disadvantages of using bottle formula.

Table 18.2.2 Breast Milk vs. Bottle Formula

| Breast Milk | Bottle Formula |

| Antibodies and lactoferrin in breast milk protect infants. | Formula does not contain immunoprotective factors. |

| The iron in breast milk is absorbed more easily. | Formula contains more iron than breast milk but it is less easily absorbed. |

| The feces that breastfed babies produce lacks smell due to different bacteria in the gut. | The feces that formula fed infants produce tends to have more of a foul odor. |

| Breast milk is always available and is always at the correct temperature. | Formula must be prepared, refrigerated for storage and warmed before given to an infant. |

| Breastfed babies are less likely to have constipation. | Formula fed babies tend to have more constipation. |

| Breastfeeding ostensibly is free, though purchasing a pump and bottles to express milk does require some expense. | Formula must be purchased and is expensive. |

| Breast milk contains the essential fatty acids, DHA and ARA, which are critical for brain and vision development. | Some formulas contain DHA and ARA. |

18.3 Infancy

Diet and nutrition have a major impact on a child’s development from infancy into the adolescent years. A healthy diet not only affects growth, but also immunity, intellectual capabilities, and emotional well-being. One of the most important jobs of parenting is making sure that children receive an adequate amount of needed nutrients to provide a strong foundation for the rest of their lives.

Infant Growth and Development

A number of major physiological changes occur during infancy. The trunk of the body grows faster than the arms and legs, while the head becomes less prominent in comparison to the limbs. Organs and organ systems grow at a rapid rate. Also during this period, countless new synapses form to link brain neurons. Two soft spots on the baby’s skull, known as fontanels, allow the skull to accommodate rapid brain growth. The posterior fontanel closes first, by eight weeks of age. The anterior fontanel closes about a year later, at 18 months on average. Developmental milestones include sitting up without support, learning to walk, teething, and vocalizing among many, many others. All of these changes require adequate nutrition to ensure development at the appropriate rate.18

this period, countless new synapses form to link brain neurons. Two soft spots on the baby’s skull, known as fontanels, allow the skull to accommodate rapid brain growth. The posterior fontanel closes first, by eight weeks of age. The anterior fontanel closes about a year later, at 18 months on average. Developmental milestones include sitting up without support, learning to walk, teething, and vocalizing among many, many others. All of these changes require adequate nutrition to ensure development at the appropriate rate.18

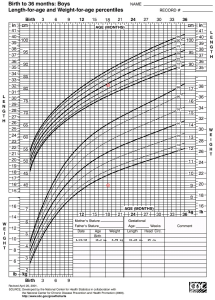

Healthy infants grow steadily, but not always at an even pace. For example, during the first year of life, height increases by 50%, while weight triples. Physicians and other health professionals use growth charts to track a baby’s development process. Because infants cannot stand, length is used instead of height to determine the rate of a child’s growth. Other important developmental measurements include head circumference and weight. All of these must be tracked and compared against standard measurements for an infant’s age.

For infants and toddlers, the WHO growth charts are used to monitor growth. These standards represent optimal growth for children at this age and allow for tracking growth trends over time through percentile rankings. Growth charts may provide warnings that a child has a medical problem or is malnourished. Insufficient weight or height gain during infancy may indicate a condition known as failure-to-thrive, which is characterized by poor growth.

Nutritional Requirements

Requirements for macronutrients and micronutrients on a per kg basis are higher during infancy than at any other stage in the human life cycle. These needs are affected by the rapid cell division that occurs during growth, which requires energy and protein, along with the nutrients that are involved in DNA synthesis. During this period, children are entirely dependent on their parents or other caregivers to meet these needs. For almost all infants, six months or younger, breast milk is the best source to fulfill nutritional requirements. An infant may require feedings 8-12 times a day or more in the beginning. After six months, infants can gradually begin to consume solid foods to help meet nutrient needs.

Energy and Macronutrients

Energy needs relative to size are much greater in an infant than an adult. A baby’s resting metabolic rate is two times that of an adult. The RDA to meet energy needs changes as an infant matures and puts on more weight. Just as we calculate energy needs in adults using various equations, there are also equations to calculate total energy expenditure and resulting energy needs for infants and children. For example, the equation for the first three months of life is: (89 x weight [kg] − 100) + 175 kcal. However, the amount and frequency an infant wants to eat will also change over time due to growth spurts, which typically occur at about two and six weeks of age, and again at about three months and six months of age.

The dietary recommendations for infants are based on the nutritional content of human breast milk. Carbohydrates make up about 45-65% of the caloric content in breast milk, which amounts to an RDA of about 130 g. Almost all of the carbohydrate in human milk is lactose, which infants digest and tolerate well. In fact, lactose intolerance is practically nonexistent in infants (not to be confused with an allergy to the protein in cow’s milk). Protein makes up about 5-20% of the caloric content of breast milk, which amounts to about 13 g per day. Infants need protein to support growth and development, though excess protein (which is only a concern with formula feeding) can cause dehydration, diarrhea, fever, and acidosis in premature infants. About 30-40% of the caloric content in breast milk is made up of fat. A high fat diet is necessary to encourage the development of neural pathways in the brain and other parts of the body. However, saturated fats and trans fatty acids inhibit this growth. Infants who are over the age of six months, which means they are no longer exclusively breastfed, should not consume foods that are high in these types of fats.

Micronutrients

Almost all of the nutrients that infants require can be met if they consume an adequate amount of breast milk. There are a few exceptions, though. Human milk is low in vitamin D, which is needed for calcium absorption and building bone, among other things. Therefore, breastfed children often need to take a vitamin D supplement in the form of drops. Infants at the highest risk for vitamin D deficiency are those with darker skin and/or no exposure to sunlight. Breast milk is also low in vitamin K, which is required for blood clotting, and deficits could lead to bleeding or hemorrhagic disease. Babies are born with limited vitamin K. Since 1961, the American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended newborns be given a low dose vitamin K injection shortly after birth.19

Breast milk is not high in iron, but the iron in breast milk is well absorbed by infants. Babies are born with about a six month supply of stored iron. After six months, however, an infant needs an additional source of iron other than breast milk. This is typically the time solid foods begin to be introduced, particularly iron-enriched cereals.20

Fluids

Infants have a high need for fluids, 1.5 ml per kcal consumed compared to 1.0 ml per kcal consumed for adults. This is because children have larger body surface area per unit of body weight and a reduced capacity for perspiration. Therefore, they are at greater risk of dehydration. However, parents or other caregivers can meet an infant’s fluid needs with breast milk or formula. As solids are introduced, parents must make sure that young children continue to drink fluids throughout the day.

Introducing Solid Foods

The American Academy of Pediatrics and the WHO recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life, followed by continued breastfeeding as complementary foods are introduced, with continuation of breastfeeding for one year or longer as mutually desired by mother and infant.14

Infants should not exclusively consume solid foods prior to six months as these do not contain the right nutrient mix that infants need. If parents try to feed an infant who is too young or is not ready, their tongue will push the food out, which is called an extrusion reflex. Further, research suggests that infants who are fed solid foods too soon are more susceptible to developing food allergies. A child may be ready to eat solids, once they can sit with little or no support, has good head control, and opens their mouth and leans toward food when it is offered.20

Solid baby foods can be bought commercially or prepared from regular food using a food processor, blender, food mill, or grinder at home. By nine months to a year, infants are able to chew soft foods and can eat solids that are well chopped or mashed. It is important to feed a young child only one new food at a time, to help identify allergic responses or food intolerances. An iron supplement or iron-fortified cereal is still recommended at this time.

18.4 Toddler Years

Major physiological changes continue into the toddler years. Unlike in infancy, the limbs grow much faster than the trunk, which gives the body a more proportionate appearance. By the end of the third year, a toddler is taller and more slender than an infant, with a more erect posture. As the child grows, bone density increases and bone tissue gradually replaces cartilage.

Developmental milestones include running, drawing, toilet training, and self-feeding. How a toddler acts, speaks, learns, and eats offers important clues about their development. By the age of two, children have advanced from infancy and are on their  way to becoming school-aged children. Their physical growth and motor development slows compared to the progress they made as infants. However, toddlers experience enormous intellectual, emotional, and social changes. Of course, food and nutrition continue to play an important role in a child’s development. During this stage, the diet completely shifts from breastfeeding or formula feeding to solid foods along with other liquids. Parents of toddlers also need to be mindful of certain nutrition-related issues that may crop up during this stage of the human life cycle. For example, fluid requirements relative to body size are higher in toddlers than in adults because children are at greater risk of dehydration.

way to becoming school-aged children. Their physical growth and motor development slows compared to the progress they made as infants. However, toddlers experience enormous intellectual, emotional, and social changes. Of course, food and nutrition continue to play an important role in a child’s development. During this stage, the diet completely shifts from breastfeeding or formula feeding to solid foods along with other liquids. Parents of toddlers also need to be mindful of certain nutrition-related issues that may crop up during this stage of the human life cycle. For example, fluid requirements relative to body size are higher in toddlers than in adults because children are at greater risk of dehydration.

The toddler years pose interesting challenges for parents or other caregivers, as children learn how to eat on their own and begin to develop personal preferences.

Nutritional Requirements

A toddler’s serving sizes should be approximately one-quarter that of an adult serving size. One way to estimate serving sizes for young children is one tablespoon for each year of life. For example, a 2 year old child would be served 2 tbsp of fruits or vegetables at a meal, while a 4 year old would be given 4 tbsp, or one-quarter cup. Here is an example of a toddler-sized meal:

- 1 oz of meat or chicken, or 2 to 3 tbsp of beans

- 1/4 slice of whole-grain bread

- 1 to 2 tbsp of cooked vegetable

- 1 to 2 tbsp of fruit

Energy

The energy requirements for ages two to three are about 1,000-1,400 kcal a day. In general, a toddler needs to consume about 40 kcal for every inch of height. For example, a young child who measures 32 inches should take in an average of 1,300 kcal a day. However, the recommended caloric intake varies with each child’s level of activity. Toddlers require small, frequent, nutritious snacks and meals to satisfy energy requirements. The amount of food a toddler needs from each food group depends on daily kcal needs. See Table 18.4.1 for serving size guidelines.

Table 18.4.1 Serving Sizes for Toddlers21

| Food Group | 2 Year olds | 3 Year olds | What Counts as: |

| Fruit | 1 c | 1-1½ c | ½ cup of fruit?

|

| Vegetables | 1 c | 1-1½ c | ½ cup of veggies?

|

| Grains | 3 oz | 3-5 oz | 1 oz grain?

|

| Protein Foods | 2 oz | 2-4 oz | 1 oz protein food?

|

| Dairy | 2 c | 2-2½ c | ½ cup dairy?

|

Macronutrients

Toddlers’ needs increase to support their body and brain development. For toddlers, the AMDR for carbohydrate intake is 45-65% of daily kcal. For protein, it’s 5-20% and for fat it’s 30-40% of daily kcal. Essential fatty acids are vital for the development of the eyes, along with nerves and other types of tissue. However, toddlers should not consume foods with high amounts of trans fats and saturated fats. Instead, young children require the equivalent of three teaspoons of healthy oils, such as olive oil, each day.

Micronutrients

As a child grows bigger, the demands for micronutrients increase. These needs for vitamins and minerals can be met with a balanced diet, with a few exceptions. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, toddlers and children of all ages need 15 mcg of vitamin D per day. Vitamin D-fortified milk and cereals can help to meet this need. However, toddlers who do not get enough of this micronutrient should receive a supplement. Pediatricians may also prescribe a fluoride supplement for toddlers who live in areas with fluoride-poor water.

Iron deficiency is also a major concern for children between the ages of two and three. Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) can cause a number of problems including weakness, pale skin, shortness of breath, fatigue, and irritability. It can also result in intellectual, behavioral, or motor problems. IDA can occur as young children are weaned from iron-rich foods, such as breast milk and iron-fortified formula. They begin to eat solid foods that may not provide enough of this nutrient. Therefore, it is important that parents and caregivers add more iron-rich foods to a child’s diet, including lean meats, fish, poultry, eggs, legumes, and iron-enriched whole-grain breads and cereals. Children may also be given a daily supplement, such as ferrous sulfate drops.

Food-Related Problems in the Toddler Years

During the toddler years, parents may face a number of problems related to food and nutrition. Possible obstacles include difficulty helping a young child overcome a fear of new foods, or fights over messy habits at the dinner table. Even in the face of problems and confrontations, parents and other caregivers must make sure their preschooler has nutritious choices at every meal. For example, even if a child stubbornly resists eating vegetables, parents should continue to provide them. Before long, the child may change their mind, and develop a taste for foods once abhorred. It is important to remember this is the time to establish or reinforce healthy habits.

Registered Dietitian Ellyn Satter states that feeding is a responsibility that is split between parent and child. According to Satter and her Division of Responsibility in Feeding, parents are responsible for what their infants eat, while infants are responsible for how much they eat. In the toddler years and beyond, parents are responsible for what children eat, when they eat, and where they eat, while children are responsible for how much food they eat and whether they eat. Satter states that the role of a parent or a caregiver in feeding includes the following22:

- selecting and preparing food

- providing regular meals and snacks

- making mealtimes pleasant

- showing children what they must learn about mealtime behavior

- being considerate of children’s lack of food experiences without catering to likes and dislikes

Picky Eaters

Children at this stage are often picky about what they want to eat. They may turn their heads away after eating just a few bites. Or they may resist coming to the table at mealtimes. They also can be unpredictable about what they want to consume for specific meals or at particular times of the day. Although it may seem as if toddlers should increase their food intake to match their level of activity, there may be a good reason for picky eating. A child’s growth rate slows after infancy, and toddlers do not require as much food.

Some children may also go through a food jag, or period of time where they only want to eat the same few foods every day and for most, if not every, meal. While this can be a way for a child to begin to express some independence, which is a normal part of development, it can make for frustrating meal times. It’s important not to force a child to eat foods they don’t want as this can actually prolong the food jag. Instead, offer new foods or healthy foods that they like and allow them to eat the preferred food with remaining food on their plate. Remember to follow Ellyn Satter’s Division of Responsibility in Feeding as stated above.

Choking

At this young age, children are still learning how to adequately chew and swallow, increasing the risk of choking. To minimize this risk, encourage children to sit when eating, chew thoroughly, play close attention to what they put in their mouths, and supervise older children who may give foods considered choking hazards to younger kids. Such foods include nuts, whole cherries or grapes, raw carrots or celery, hard candy, hot dogs, etc. Make sure to cut foods into smaller and/or mashed pieces.

Early Childhood Caries

Early childhood caries (dental issues such as cavities) remain a potential problem during the toddler years. The risk of early childhood caries increases with the consumption of foods with a higher sugar content. According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, children between ages of 2 and 5 consume slightly more than 200 kcal of added sugar per day or approximately 13% of their total kcal.26 This is much more than recommended. Therefore, parents with toddlers should avoid processed foods, such as snacks from vending machines, and sugary beverages, such as soda. Parents also need to instruct a child on brushing their teeth at this time to help a toddler develop healthy habits and avoid tooth decay.

Toddler Obesity

Another potential problem during the early childhood years is toddler obesity. According to the WHO, the number of overweight or obese infants and young children (five years and younger) has increased from 32 million globally in 1990 to 41 million in 2016.23 In the US, the proportion of obese two to five year-olds increased from 5% in the 1970s to 13.9% in 2015.24,25

Obesity during early childhood tends to linger as a child matures and can cause health problems later in life. Recall from Chapter 9 that children undergo both hyperplasia and hypertrophy of adipose tissue, and the additional adipose cells created during childhood remain in adulthood. There are a number of reasons for the increases in obesity rates in toddlers. One is a lack of time. Parents and other caregivers who are constantly on the go may find it difficult to fit home-cooked meals into a busy schedule and may turn to fast food and other conveniences that are quick and easy, but not nutritionally sound. Another contributing factor is a lack of access to fresh fruits and vegetables. This is a problem particularly in low-income neighborhoods where local stores and markets may not stock fresh produce or may have limited affordable options. Physical inactivity is also a factor, as toddlers who live a sedentary lifestyle are more likely to be overweight or obese. Another contributor is a lack of breastfeeding support. Children who were breastfed as infants show lower rates of obesity than children who were formula-fed.

To prevent or address toddler obesity parents and caregivers can do the following:

- Eat at the kitchen table instead of in front of a television to monitor what and how much a child eats.

- Offer a child healthy portions. The size of a toddler’s fist is an appropriate serving size.

- Toddlers should be physically active throughout the day, with no more than 60 minutes of sedentary activity, such as watching television, per day.

Food for Thought

What would you recommend to help families prevent obesity among their children? What tips would you provide? What lifestyle changes might help?

18.5 Childhood

Nutritional needs change as children leave the toddler years. From ages four to eight, school-aged children grow consistently, but at a slower rate than infants and toddlers. They also experience the loss of deciduous, or “baby” teeth, and the arrival of permanent “adult” teeth, which typically begins at age six or seven. As new teeth come in, many children have some malocclusion, or malposition, of their teeth, which may affect their ability to chew food. Other changes that affect nutrition include the influence of peers on dietary choices and the kinds of foods offered by schools and after-school programs, which can make up a sizable part of a child’s diet. Excessive weight gain early in life can lead to obesity into adolescence and adulthood.

At this life stage, a healthy diet facilitates physical and mental development and helps to maintain health and wellness. School-aged children experience steady, consistent growth, with an average growth rate of 2 to 3 inches in height and 4.5 to 6.5 lb in weight per year. In addition, the rate of growth for the extremities is faster than for the trunk, which results in more adult-like proportions.

Nutritional Requirements

Energy

Children’s energy needs vary depending on their growth and level of physical activity. Energy requirements may also vary according to biological sex. Girls ages 4 to 8 require 1,200-1,800 kcal a day, while boys need 1,200-2,000 kcal daily and, depending on their activity level, a child may require more. Also, recommended intakes of macronutrients and most micronutrients are higher relative to body size, compared with nutrient needs during adulthood.

Macronutrients

For carbohydrates, the AMDR remains 45-65% of daily kcal. Children also require 17-25 g of fiber per day. They have a high need for protein to support muscle growth and development, therefore the AMDR increases a bit to 10-30% of daily kcal. High levels of essential fatty acids are needed to support growth (although not as high as in infancy and toddler years). As a result, the AMDR for fat is 25-35% of daily kcal.

Micronutrients

Micronutrient needs should be met with foods first. Parents and caregivers should select a variety of foods from each food group to ensure that nutritional requirements are met. Because children grow rapidly, they require foods that are high in iron, such as lean meats, legumes, fish, poultry, and iron-enriched cereals. Adequate fluoride is crucial to support strong teeth. Two of the most important micronutrient requirements during childhood are adequate calcium and vitamin D intake. Both are needed to build dense bones and a strong skeleton. Children who do not consume adequate vitamin D should be given a supplement of 10 mcg per day. Table 18.5.1 shows the micronutrient recommendations for school-aged children. Note that the recommendations are the same for boys and girls. As we progress through the different stages of the human life cycle, there will be some differences between males and females regarding micronutrient needs.

Table 18.5.1 Recommended Micronutrient Intakes during Childhood

| Nutrient | 4-8 Years | 9-13 Years |

| Vitamin A (mcg) | 400.0 | 600.0 |

| Thiamin (mg) | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| Riboflavin (mg) | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| Niacin (mg) | 8.0 | 12.0 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| Folate (mcg) | 200.0 | 200.0 |

| Vitamin B12 (mcg) | 1.2 | 1.8 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 25.0 | 45.0 |

| Vitamin D (mcg) | 15.0 | 15.0 |

| Vitamin E (mg) | 7.0 | 11.0 |

| Vitamin K (mcg) | 55.0 | 60.0 |

| Calcium (mg) | 1000.0 | 1300.0 |

| Iron (mg) | 10.0 | 8.0 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 130.0 | 240.0 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 500.0 | 1250.0 |

| Selenium (mcg) | 30.0 | 40.0 |

| Zinc (mg) | 5.0 | 8.0 |

Factors Influencing Intake

A number of factors can influence children’s eating habits and attitudes toward food. Family environment, societal trends, taste preferences, and messages in the media all impact the emotions that children develop in relation to their diet. Television commercials can entice children to consume sugary products, fatty fast foods, excess kcal, refined ingredients, and sodium. Therefore, it is critical that parents and caregivers direct children toward healthy choices.

One way to encourage children to eat healthy foods is to make meals and snacks fun and interesting. Parents should include children in food planning and preparation, for example selecting items while grocery shopping or helping to prepare part of a meal, such as making a salad. At this time, parents can also educate children about kitchen safety. It might be helpful to cut sandwiches, meats, or pancakes into small or interesting shapes. In addition, parents should offer nutritious desserts, such as fresh fruits, instead of calorie-laden cookies, cakes, salty snacks, and ice cream. Additionally, research has found that regularly eating dinner as a family is associated with greater consumption of fruits, vegetables, and less saturated and trans fat.27

18.6 Adolescence

The onset of puberty is the beginning of adolescence and is the bridge between the childhood years and young adulthood. According to the DRI recommendations, adolescence is divided into two age groups: 9 through 13 years, and 14 through 18 years. Some of the important physiological changes that take place during this stage include the development of the primary sex characteristics (the reproductive organs), along with the onset of menstruation in females. This life stage is also characterized by the appearance of secondary sex characteristics, such as the growth of facial and body hair, the development of breasts in girls, the deepening of the voice in boys, and alterations in body proportions. All of these changes, as well as the accompanying mental and emotional adjustments, should be supported with sound nutrition.

The Onset of Puberty (Ages 9 through 13 years)

This period of physical development is divided into two phases. The first phase involves height increases from 20-25%. Puberty is second to the prenatal period in terms of rapid growth as the long bones stretch to their final, adult size. Girls typically grow 2 to 8 inches taller, while boys grow 4 to 12 inches taller. The second phase involves weight gain related to the development of bone, muscle, and fat tissue.

Energy and Macronutrients

The energy requirements for preteens differ according to biological sex, growth, and activity level. For ages 9 to 13, girls should consume about 1,400-2,200 kcal per day and boys should consume 1,600-2,600 kcal per day. Physically active preteens who regularly participate in sports or exercise need to eat a greater number of kcal to account for increased energy expenditures.

The energy requirements for preteens differ according to biological sex, growth, and activity level. For ages 9 to 13, girls should consume about 1,400-2,200 kcal per day and boys should consume 1,600-2,600 kcal per day. Physically active preteens who regularly participate in sports or exercise need to eat a greater number of kcal to account for increased energy expenditures.

The AMDR recommendations remain 45-65% of total kcal from carbohydrates, 10-30% from protein, and 25-35% from fat. Foods that are high in fiber should make up the bulk of carbohydrate intake.

Micronutrients

Key vitamins needed during puberty include vitamins B12, D, and K. Adequate calcium intake is essential for building bone and preventing osteoporosis later in life. Young females need more iron beginning at the onset of menstruation, while young males need additional iron for the development of lean body mass. Almost all of these needs should be met with dietary choices, not supplements (although iron may be an exception). See Table 18.6.1 for specific recommended micronutrients amounts.

Late Adolescence (Ages 14 through 18 years)

After puberty, the rate of physical growth slows down. Girls stop growing taller around age 16, while boys continue to grow until ages 18-20. One of the psychological and emotional changes that takes place during this life stage includes the desire for independence as adolescents develop individual identities apart from their families. As teenagers make more and more of their own dietary decisions, parents or other caregivers and authority figures should guide them toward appropriate, nutritious choices. One way that teenagers assert their independence is by choosing what to eat. They often have their own money to purchase food and tend to eat more meals away from home. Older adolescents also can be curious and open to new ideas, which includes trying new kinds of food and experimenting with their diet. For example, teens will sometimes skip a main meal and snack instead. That is not necessarily problematic. Their choice of food is more important than the time or place.

However, too many poor choices can make young people nutritionally vulnerable. Teens should be discouraged from eating fast food, which has a high fat, sugar, and sodium content, or frequenting convenience stores and using vending machines, which typically offer poor nutritional selections. Other challenges that teens may face include obesity and eating disorders. At this life stage, young people still need guidance from parents and other caregivers about nutrition-related matters. It can be helpful to explain to young people how healthy eating habits can support activities they enjoy, such as skateboarding or dancing, or connect to their desires or interests, such as athletic performance or improved cognition.

However, too many poor choices can make young people nutritionally vulnerable. Teens should be discouraged from eating fast food, which has a high fat, sugar, and sodium content, or frequenting convenience stores and using vending machines, which typically offer poor nutritional selections. Other challenges that teens may face include obesity and eating disorders. At this life stage, young people still need guidance from parents and other caregivers about nutrition-related matters. It can be helpful to explain to young people how healthy eating habits can support activities they enjoy, such as skateboarding or dancing, or connect to their desires or interests, such as athletic performance or improved cognition.

As during puberty, growth and development during adolescence differs in males and females. Teenage girls experience a significant increase in body fat, while teenage boys often experience an increase in fat-free and skeletal mass, and a decrease in body fat.28 For both males and females, primary and secondary sex characteristics have fully developed and the rate of growth slows with the end of puberty.

Energy and Macronutrients

Adolescents have increased appetites due to increased nutritional requirements. Nutrient needs are greater in adolescence than at any other time in the life cycle, except during pregnancy. The energy requirements for ages 14 to 18 are 1,800-2,400 kcal for girls and 2,000-3,200 kcal for boys, depending on activity level. The extra energy required for physical development during the teenage years should be obtained from foods that provide nutrients instead of “empty calories.” Also, teens who participate in athletics must make sure to meet their increased energy needs.

Older adolescents are more responsible for their dietary choices than younger children, but parents and caregivers must make sure that teens continue to meet their nutrient needs. The AMDR for carbohydrates remains 45-65% of daily kcal and the adequate intake (AI) of fiber is 25-34 g per day (depending on daily kcal intake). Adolescents require more servings of grain than younger children, and should eat whole grains, such as wheat, oats, barley, and brown rice. The NAM recommends higher intakes of protein for growth in the adolescent population. The AMDR for protein remains 10-30% of daily kcal and lean proteins, such as meat, poultry, fish, beans, nuts, and seeds are excellent ways to meet those nutritional needs. The AMDR for fat remains 25-35% of daily kcal. It is also essential for young athletes and other physically active teens to intake enough fluids, because they are at a higher risk for becoming dehydrated.

Micronutrients

Micronutrient recommendations for adolescents are mostly the same as for adults, though children this age need more of certain minerals to promote bone growth (e.g., calcium and phosphorus, along with iron and zinc for girls). Again, vitamins and minerals should be obtained from food first, with supplementation for certain micronutrients only (such as iron).

The most important micronutrients for adolescents are calcium, vitamin D, vitamin A, and iron. Adequate calcium and vitamin D are essential for building bone mass. The recommendation for calcium is 1,300 mg for both boys and girls. Low-fat milk and cheeses are excellent sources of calcium and help young people avoid saturated fat and cholesterol. It can also be helpful for adolescents to consume products fortified with calcium, such as breakfast cereals and orange juice. Iron supports the growth of muscle and lean body mass. Adolescent girls also need to ensure sufficient iron intake as they start to menstruate. Girls ages 12 to 18 require 15 mg of iron per day. Increased amounts of vitamin C from orange juice and other sources can aid in iron absorption. Also, adequate fruit and vegetable intake allows for meeting vitamin A needs.

Table 18.6.1 Recommended Micronutrient Intakes during Adolescence

| Nutrient | Females, 14-18 Years | Males, 14-18 Years |

| Vitamin A (mcg) | 700.0 | 900.0 |

| Thiamin (mg) | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| Riboflavin (mg) | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| Niacin (mg) | 14 | 16 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| Folate (mcg) | 400.0 | 300.0 |

| Vitamin B12 (mcg) | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 65.0 | 75.0 |

| Vitamin D (mcg) | 15.0 | 15.0 |

| Vitamin E (mg) | 15.0 | 15.0 |

| Vitamin K (mcg) | 75.0 | 75.0 |

| Calcium (mg) | 1300.0 | 1300.0 |

| Iron (mg) | 15.0 | 11.0 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 360.0 | 410.0 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 1250.0 | 1250.0 |

| Selenium (mcg) | 55.0 | 55.0 |

| Zinc (mg) | 9.0 | 11.0 |

18.7 Adulthood

Adulthood begins at the end of adolescence and continues until the end of one’s life.

Young Adulthood

Young adulthood is the period from ages 19 to 30 years. It is a stable time compared to childhood and adolescence. Physical growth has been completed and all of the organs and body systems are fully developed. Typically, a young adult who is active has reached his or her physical peak and is in prime health. During this life stage, it is important to continue to practice good nutrition. Healthy eating habits promote metabolic functioning, assist repair and regeneration, and prevent the development of chronic conditions. Proper nutrition and adequate physical activity at this stage not only promote wellness in the present, but also provide a solid foundation for the future.

With the onset of adulthood, good nutrition can help young adults enjoy an active lifestyle. The body of an adult does not need to devote its energy and resources to support the rapid growth and development that characterizes youth. However, the choices made during those formative years can have a lasting impact. Eating habits and preferences developed during childhood and adolescence influence health and fitness into adulthood. Some adults have gotten a healthy start and have established a sound diet and regular activity program, which helps them remain in good condition from young adulthood into their later years. Others carry childhood obesity into adulthood, which adversely affects their health. However, it is not too late to change course and develop healthier habits and lifestyle choices. Therefore, adults must monitor their dietary decisions and make sure their caloric intake provides the energy that they require, without going into excess.

Energy and Macronutrients

Young men typically have higher nutrient needs than young women. For ages 19-30, the energy requirements for women are 1,800-2,400 kcal, and 2,400-3,000 kcal for men, depending on activity level. These estimates do not include women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, who require a higher energy intake. For carbohydrates, the AMDR continues to be 45-65% of daily kcal. All adults, young and old, should eat fewer energy dense carbohydrates, especially refined, sugar dense sources, particularly for those who lead a more sedentary lifestyle. The AMDR for protein is 10-35% of total daily kcal, and should include a variety of lean meat and poultry, eggs, beans, peas, nuts, and seeds. The guidelines also recommend that adults eat at least two 4 oz servings of seafood per week.

It is also important to replace foods that are high in saturated fat with ones that are lower in solid fats and kcal. All adults should limit total fat to 20-35% of their daily kcal and keep saturated fatty acids to less than 10% of total kcal by replacing them with monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids. The adequate intake for fiber is 22-28 g per day for women and 28-34 g per day for men. Soluble fiber may help improve cholesterol and blood sugar levels, while insoluble fiber can help prevent constipation.

Micronutrients